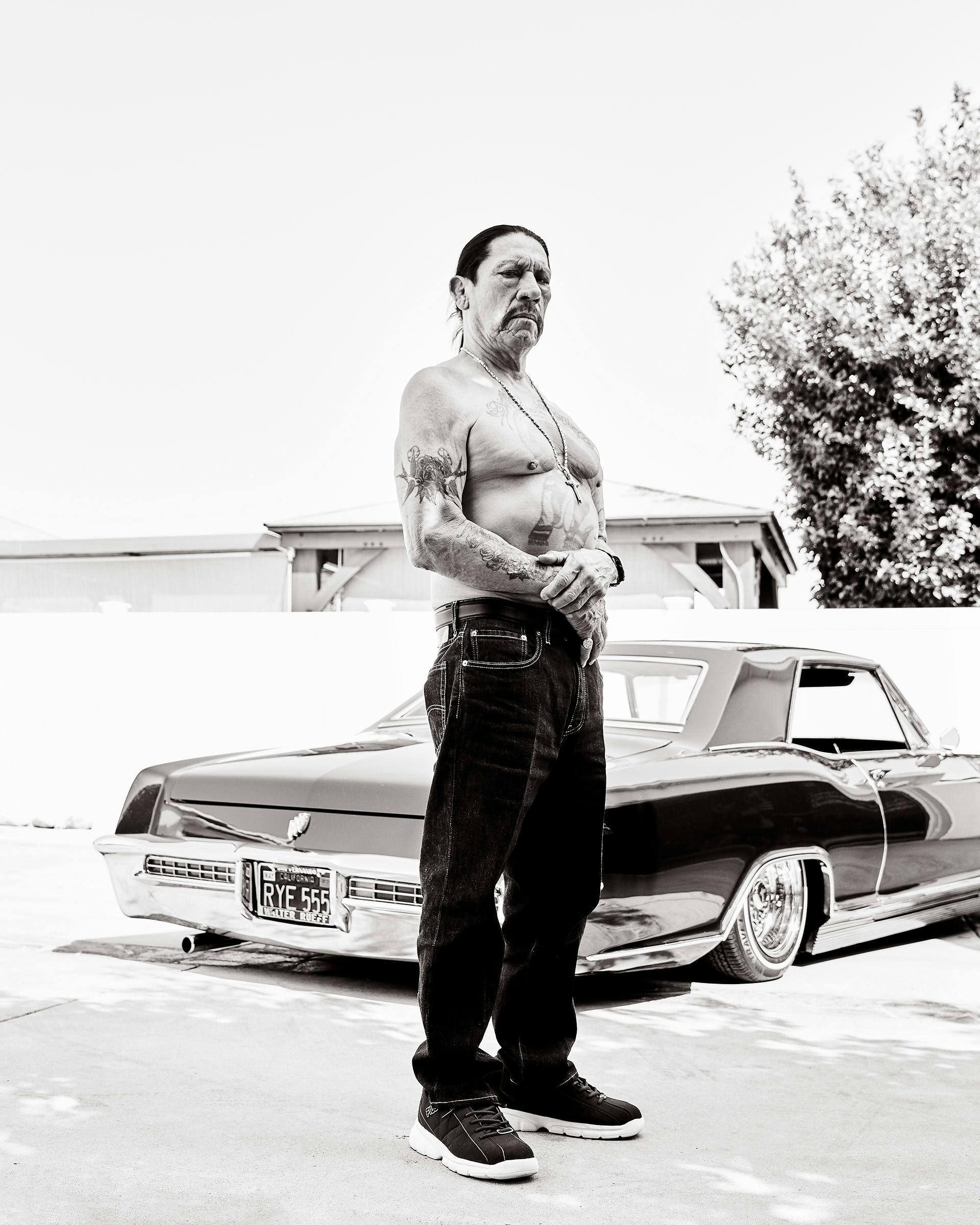

The lines across Danny Trejo’s face let you know that he’s lived. They can twist into the scowl that helped him intimidate other inmates at San Quentin, Soledad, Folsom, and Vacaville California state prisons. They clue you in to years of hard-won brawls and boxing matches and tell stories of adolescent scraps before he wound up in the juvenile justice system or in championship matches at state penitentiaries. But there are also the lines that form at the corner of his eyes and the ones that frame his mouth right before he lets out his signature laugh.

It’s more like a chuckle, actually—one that blossoms from his stomach when he undercuts a painful anecdote with a quick joke or when his adopted pup Penny Lane trots into his living room. “Hi, baby. Come here, my baby,” he coos at the gray poodle mix, who competes for his attention over a Zoom call. He lets out another belly laugh before confiding, “This is the most jealous dog in the world.”

It’s an unexpected moment from someone whose nearly four hundred acting credits have largely featured him playing drug dealers, inmates, or murderers. Trejo’s face, and the scars it bears, has become instantly recognizable and nearly synonymous with the tough-guy image, lending a certain credibility to the dangerous characters he’s portrayed.

In reality, the actor has spent the past fifty years of his life atoning for his violent past. Despite being one of the most prolific actors in Hollywood, Trejo still lives just five miles away from his childhood home in Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley; he feels that he still owes something to the streets he once terrorized.

Trejo spent eleven years in and out of the prison system, doing his first stint in jail in 1962 for drug dealing and robbery. His final stay began in 1965, after he sold four ounces of heroin (he says it was actually just sugar) to an undercover federal agent. In 1968, when he was 24, a prison riot that broke out on Cinco de Mayo in Soledad state prison landed Trejo in solitary after he hit a guard in the head with a rock (Trejo maintains that the guard wasn’t his intended target). When he recounts this incident, it’s like the actor is talking about an entirely different person. “You can become a bit of a sociopath [in prison], and I think I just stopped caring,” he says.

Now, at age 76, Trejo has continued to redefine himself. He’s been sober for more than half a century, and his decades-long film career has afforded him the luxury of being able to open a handful of businesses, including the aptly named Trejo’s Tacos, Trejo’s Coffee & Donuts, and, most recently, Trejo’s Music. The record label for emerging artists released a Chicano soul album in 2019 featuring Baby Bash, Frankie J, and Chiquis Rivera. And though he’s become synonymous with the character Machete (his most popular role, in the Robert Rodriguez film of the same name), his latest projects are decidedly more personal, with a cookbook and a recently released documentary diving into his L.A. roots and Mexican American upbringing. It’s clear that after being stereotyped for most of his life, Trejo is now enjoying the freedom to forge his own path.

Throughout much of our conversation, Trejo laughs and cracks jokes at even his darkest memories. But his tone changes as he recalls the first moment he pulled up to San Quentin—California’s only prison with a death row for men, with an infamous gas chamber and a host of high-profile inmates that included Charles Manson and several of his associates. Trejo remembers being awestruck by the prison’s gray walls, which glowed eerily in the moonlight as he came in on the bus. “When you pull up to San Quentin, you see two lights up on top of the North Block,” he tells me, his voice catching before he continues. “You see a red light and a green light. If the red light is on, that means they’re killing someone,” according to prison lore. “That’s the first thing you see, so you know this is a death house—people come in here and don’t come out.”

By the late sixties, as he details in his recently released documentary, Inmate #1: The Rise of Danny Trejo, he had been in and out of correctional facilities for more than half of his life. It was hard to scare him, but San Quentin took his breath away. Trejo says he could taste the tension of the prison in his mouth, comparing it to the bitter sting of a cold copper penny on his tongue. It’s the same taste he could smell on his own breath and on his opponent’s in the moments before a fight. “It’s a manifestation of all the anger, all the hate and fear coming up,” he says. “It almost makes you throw up.”

Years of navigating a system in which your only options are to become predator or prey had softened that bitter taste—the only cue he had left to tap into his emotions. “The minute you get comfortable with the tension,” he cautions, “you have become a sociopath.”

After the prison riot, he entertained himself in solitary by going over his favorite films in his head, sometimes acting out scenes from The Wizard of Oz to keep his mind active. Accused of the assault and potentially attempted murder of a guard, he was convinced that he was headed to death row. So he prayed to God.

Growing up in a Mexican American family in the fifties, Trejo was raised Catholic. His grandmother would always put money in the offering basket, no matter how little she had for herself. He struggled to understand her devotion, but as he sat in a cell where “God sucks” had been written in feces on the wall, striking up a conversation with God seemed like the only thing left to try. “I made a deal,” he says. “I told him, ‘Let me die with dignity. You don’t need to get me out of this, I know what I’ve done. Just let me die with dignity and I’ll say your name every day. I’ll do whatever I can for my fellow man.’”

Eventually, as no witnesses came forward to corroborate the claims against Trejo, the charges were dropped. He was released from solitary and paroled in August 1969. He had no plan and no real prospects for the future, but he was determined to leave ten years of crime behind him. To hear him tell it, it was like he was born again. To hear his friends tell it is to believe he actually was.

One of those friends is Mario Castillo, who first met Trejo in 1991 at San Quentin while the actor was there filming Blood In, Blood Out. Castillo was a prisoner at the time, not remotely interested in getting clean, but Trejo reached out, trying to convince him to get help for his heroin addiction. After his release in 1996, Castillo (now sober) developed a friendship with Trejo, accompanying him to speak at juvenile hall and recovery centers across the state. “Danny’s always helping someone,” he says. “When I see the kids at juvenile hall, they really pay attention to him and what he’s saying. I wish I’d had that when I was there.”

With prison behind him, Trejo returned to Pacoima, a predominantly Hispanic Los Angeles neighborhood.

Trejo had been getting himself into trouble for as long as he could remember. In his teens, he and his friends had committed a string of carjackings and armed robberies at practically every corner store in a ten-mile radius. His family briefly sent him to live with relatives in San Antonio, hoping a change of scenery would straighten him out. One scorching Texas summer was enough to have him asking to come back to California. His father was a bit rough around the edges, a gruff Mexican man who wasn’t particularly affectionate. Trejo preferred spending time with his uncle Gilbert, a Golden Gloves boxer with a penchant for drugs and flashy cars. It was Gilbert who first taught Trejo to fight, who gave him his first hit of weed at eight years old, and who administered his first injection of heroin at twelve.

From the moment he first ended up in juvenile hall at twelve years old, Trejo felt that becoming a criminal was one of his only options. “I thought Mexicans were supposed to go to jail,” he tells me. “It was nothing but guys just like me and African Americans.” After his release from prison, Trejo was determined not to let himself slip up. He started gardening and doing chores for cash, supplementing his income with earnings from local boxing matches. Even when his uncle made enticing offers to get him back in the game as a drug dealer, Trejo refused, eventually getting a job as a drug counselor at a local clinic where he still works part-time today. He’s been clean for 51 years.

While the counseling job was critical to his own recovery process, it also helped him break into acting. In 1984, an addict and actor whom Trejo was sponsoring told him that he was struggling with temptation on the set of Runaway Train, an action-thriller centered on two escaped convicts. Trejo came to the set to help; while he was there, he immediately drew the attention of director Andrei Konchalovsky, who cast him in a small part as a boxer. It was good money, much better than he had been making from odd jobs. So for the next five years, Trejo played roles like “cholo,” “bodyguard,” and “prisoner,” as his reputation in the industry grew. “Every time I would show up on set, the director would ask me to take off my shirt,” he laughs. “They wanted to see the big charra on my chest. That’s a prison tattoo—that lets you know I was there.”

It’s still hilarious to him—cue dozens of anecdotes marked by that trademark chuckle—that he was getting paid to pretend to be the person he had been for years, the same one he was working to leave behind. At the suggestion of his directors, he’d add prison slang to his lines for a more authentic feel. He would offer advice on how a group of robbers might try to pull off a particular job. He would yell and glower, and when the cameras stopped rolling, his fellow castmates would ask him where he’d studied. “I’d tell them, ‘Vons, Thrifty’s, Piggly Wiggly—all the stores we robbed. All of that was second nature to me.”

In his book Latino Images in Film: Stereotypes, Subversion, and Resistance, Charles Ramirez Berg, a film professor at the University of Texas at Austin, lays out six stereotypes that have defined the representation of Latinos in film over the past century. There’s the bandito, the harlot, the buffoon or clown, the Latin lover, and the dark lady. Historically, these archetypes have functioned as a way of putting Latino characters into a box, mocking them, or confining them to roles in which they’re the foil or sidekick to a white lead. For most of his career, Trejo inhabited the role of the bandito—someone whose scars and brown skin were enough to convey that he was a bad man, with little to no backstory or dialogue about his life or motivation.

Trejo didn’t (and still doesn’t) resent being typecast. After all, “I am a mean Mexican guy with tattoos,” he jokes. For him, it was more about signing on to roles where the bad guy didn’t win. Picking parts where his character ended up dead or in prison was his own way of showing viewers where a life of drugs and crime can lead. It also helped Trejo break Christopher Lee’s record for the most movie deaths on screen: he’s perished 65 times.

But in the early nineties, a small part in Robert Rodriguez’s Desperado (1995) kicked off Trejo’s most famous creative partnership and, eventually, led to the character with whom he would become synonymous.

Rodriguez gave Trejo the role of Navajas on sight. The character never speaks throughout the film; he’s a mysterious hitman who silently wields knives to intimidate and attack his targets. Right from the start, Rodriguez had ambitions for Trejo. “Danny’s face is so iconic,” Rodriguez says. “But he also has a sweetness and a humanity in him that you want in a role. … You can put him up onto a big screen, and you know it’s just going to be something special.”

As early as 1994, the San Antonio–born director had been toying with the idea of a “Mexploitation” film—a play on the blaxploitation films popularized in the seventies, this time centered around a Mexican hero called Machete, an ex-federale out for revenge. Trejo was the only person for the role, but Rodriguez believed that the actor needed more star power before he could helm a major blockbuster. So he cast him in the From Dusk Till Dawn franchise, then the Spy Kids trilogy as Uncle Machete (according to Rodriguez, while Uncle Machete and Machete share the same name, they exist in alternate universes). Over the span of a decade, Trejo went from bit parts to acting in scenes alongside Robert De Niro, Bryan Cranston, George Clooney, and Nicolas Cage.

His role as Uncle Machete allowed Trejo to trade in the tough-guy act and show the world a bit of his heart. Soon, he was getting recognized by fans across the world. So when Rodriguez released a parody trailer for the Machete film, the demand to see the project come to fruition was immediate. “Danny and I couldn’t go down the street without people asking for the movie,” Rodriguez says. “People needed it. They wanted a badass Latino character because they’d never seen it before. And it was like, ‘Yeah, why doesn’t that exist?’”

I was first introduced to Danny Trejo as Uncle Machete. I was four years old when the first Spy Kids film premiered in 2001, but I remember being ecstatic at how familiar the characters felt to my own Mexican family. Even Trejo’s character—a loving, rough-around-the-edges uncle—reminded me of my tíos. From behind the lens of his camera, Rodriguez delivered Latino protagonists to a demographic that had been starved for them. By the time Machete premiered nine years later, representation wasn’t much better. It might seem easy to minimize the cultural impact of a film like Machete—one in which the main character literally uses a man’s intestines to rappel out of a window. The movie is absurd and gratuitous in its violence, but it also incisively parodies the toxic machismo that ruled Trejo’s own childhood household. Machete also remains one of the few major blockbuster franchises (the film grossed $44 million worldwide, peaking at number two at the box office) to feature a Latino leading man. For the first time, Trejo was the hero. His character is the romantic lead, the one everyone in the audience is rooting for, without being the Antonio Banderas Latin-lover type. He’s imperfect, but he’s not only on the big screen; he’s also shaping the story.

The film and its promotion also responded to a growing anti-immigrant sentiment in the U.S. Machete’s central drama rests on the campaign of fictional Texas state senator John McLaughlin (Robert De Niro) campaign to secure the U.S.-Mexico border. After being blackmailed into executing a hit on McLaughlin, Machete discovers it was a setup meant to paint him as a dangerous Mexican immigrant, drawing support for the senator’s plans to build an electrified border fence. Though the story line had been in the works for years, the film’s premiere came on the heels of Arizona’s Senate Bill 1070, one of the strictest anti-immigration laws passed in the country. A new trailer was released in response, featuring Trejo calling out Arizona; the trailer later cuts to an uprising of immigrants.

The film made Trejo a bona fide star, a leading man who could carry a project. In the year following Machete’s release, more than one kid showed up at his doorstep dressed as the character, and even his own mother began calling him Machete. “It was the first time that we had a real superhero,” he says proudly.

During the pandemic, Trejo says, he’s adjusted easily to social distancing and staying at home—after all, sheltering in place is a breeze compared with surviving eighteen months in solitary. He’ll appear in two horror films with release dates this fall: Murder in the Woods and The Last Exorcist. Trejo has stayed busy: between promoting his documentary and cookbook, plus overseeing his restaurants and record label and keeping up his recovery work, it’s largely been business as usual, just with a mask on. If there’s one thing that you can immediately tell from speaking with Trejo, it’s that he never does anything halfway.

Take his attention to detail at his restaurant. He won’t take sides in the great Cal-Mex versus Tex-Mex debate (he has family on both sides), and instead makes sure that the menu at Trejo’s Tacos offers a little bit of everything. He eats at all of his establishments, and if he can’t make it, he sends his friends to grab a meal on him. “They’ll ask me if I want them to wear a wire, and I’m like, ‘No just go in and order some food, fool,’” he laughs. The restaurant is the result of a childhood dream of Trejo’s—he and his mother had always talked about opening a taco stand of their own. Last year, Trejo’s Tacos sponsored a professional boxer from Los Angeles, Seniesa Estrada. Trejo makes sure to tell me about her, emphasizing her undefeated record like a proud dad, encouraging me to look her up. Even with Estrada, the sponsorship isn’t just a title. She says she frequently gets calls from him checking in, and he even drives to Mexico to cheer her on, standing just outside the ring.

Trejo’s the kind of guy who helps rescue a child from an overturned vehicle (yes, really) and doesn’t hesitate to revisit the same prisons that he was detained in to talk to the inmates there now. Though these talks are usually about the dangers of a life of crime, more recently, they’ve also been about encouraging eligible inmates to vote. In the pandemic, he’s put up signs congratulating 2020 graduates and popped out to take pictures with fans. He’s now working on an autobiography, one that’ll go into more detail than his documentary about his family.

While he enjoys acting, ultimately, he says, it’s just a job, one that helped him provide for his three kids. One of them might even follow him into the movie business: his son Gilbert, 32, recently directed his dad in the film From a Son. Years before he was an actor, Trejo was famous in their neighborhood for helping people get sober. In their tight-knit community, Gilbert watched as people approached his father on the street just to say they’d enjoyed what he’d said at a Narcotics Anonymous meeting, or to thank him for counseling their child. Six years ago, Trejo was part of Gilbert’s own journey to sobriety. Though it’s not a direct comparison, that time in their lives serves as the basis for Gilbert’s upcoming film, which follows a father’s desperate quest to find his drug-addicted son.

In one particularly emotional scene, Trejo’s character breaks down crying as he searches for his son through the desert. “To me, acting was always on the surface, it was superficial yelling and violence,” Trejo says. “I could do that all day, but this was someone who was in pain and scared to death that his son was gone. This was real emotion. It’s the biggest thing I’ve ever done.”

Gilbert hopes the role will help people see his father as a serious actor, not just an action hero. “It was the first time I saw my dad cry in my entire life,” Gilbert says. “Physically being there in the room was heavy, but it was really cathartic seeing him be so vulnerable.”

Trejo still talks to God, although his God is more like a cheerleader than the more punishing deity that he and many other Mexican Americans grew up with. His God is someone he can have casual check-ins with, a voice encouraging him from the sidelines after delivering him from the depths of a ninety-square-foot cell. “I talked to God a couple of days ago and I said, ‘How am I doing?’” he tells me. “And he said, ‘You’re almost out of hell. Keep it up, you’re doing great.’”

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Television

- Longreads

- Robert Rodriguez