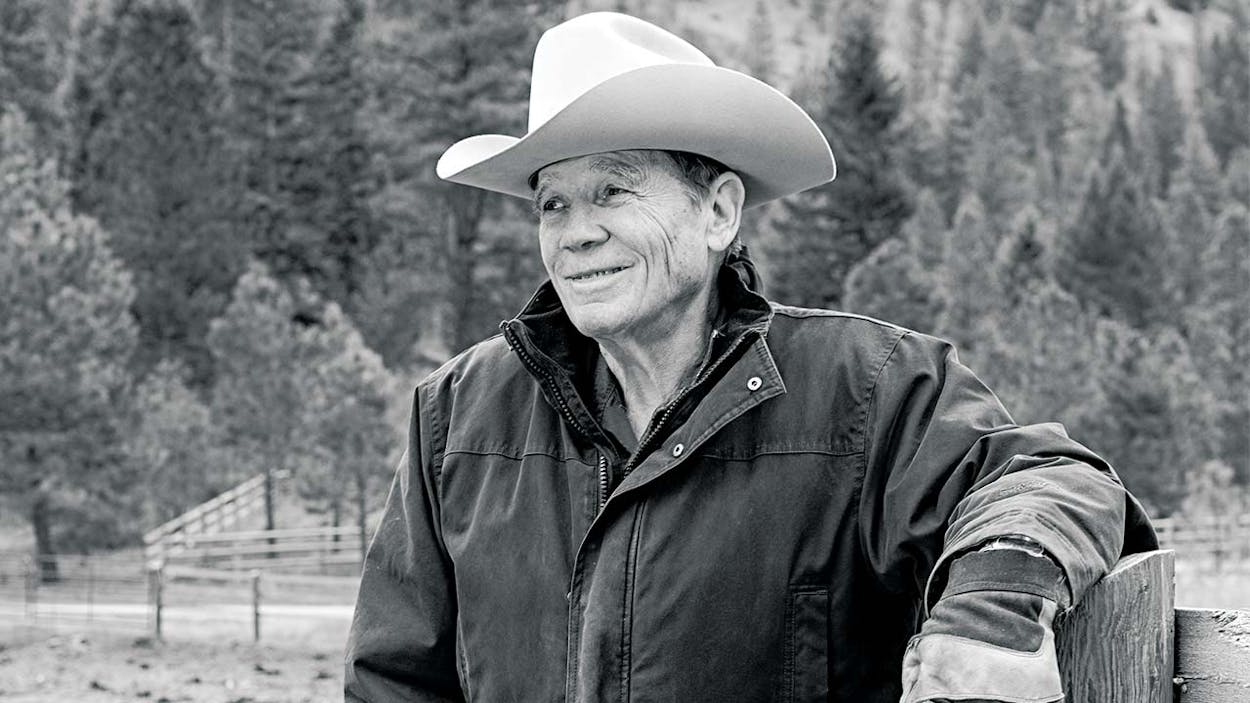

James Lee Burke is best known for his mystery novels featuring Dave Robicheaux, a sheriff’s deputy in New Iberia, Louisiana. But though he has spent much of his life in the Pelican State, Burke was born in Houston and has deep roots in Texas, and in recent years those ties have come to play a more prominent role in his work. In 1997 he began a series of books about a Texas lawyer named Billy Bob Holland. A decade or so later he wrote two books about Billy Bob’s cousin, Texas sheriff Hackberry Holland. Last year’s Wayfaring Stranger and Burke’s new book, House of the Rising Sun, continue the Holland family saga.

Jeff Salamon: So, to help make things clear for our readers: your new book, House of the Rising Sun, is about a Texas lawman named Hackberry Holland. But it’s not the same Texas lawman named Hackberry Holland whom you have written previous books about.

James Lee Burke: Yes. This book is about the Hackberry Holland who was a lawman from roughly 1880 to the close of the nineteenth century. The other books are about his grandson, Hackberry Holland, who was a Navy corpsman in Korea and later, as an older man, went into politics and became a sheriff down on the border. People get confused about it sometimes.

JS: Is this Hackberry Holland based on anyone real?

JLB: The names of my characters are the real names of my mother’s family. The patriarch of the family was a gunfighter named Sam Morgan Holland, and he was a legend for all the wrong reasons. He was an alcoholic, a violent man, very self-destructive. During Reconstruction he trailed cows from Yoakum, which was the inception point of the Chisholm Trail, up through San Antonio into Wichita—two thousand head at a time. I have part of his diary in which he described bedding down his cows right outside the pens in Wichita, and there was dry lightning. His cows got loose on him and he chased them all over south Kansas and into Indian Territory, which is what Oklahoma was called then. He wrote that he cursed God for his bad fortune and then he got drunk. There were only three words that went though his mind all the way back to Texas—“whiskey” and “whiskey” and “whiskey.”

But then he began to sit at the New Hebron Baptist Church each Sunday on what was called the mourner’s bench. Have you ever heard that term?

JS: I have not.

JLB: The mourner’s bench was for people in despair who were thought to be beyond the pale. Of course, they didn’t understand addiction back then, or clinical depression, which is what Sam Holland suffered from. Then, he said, one day his depression lifted “like a veil of ash from a dead fire.” And he became a saddle preacher and he preached on the Chisholm Trail for the rest of his life. He had killed nine men in gun duels and he was haunted by his deeds. It’s quite a story.

JS: Is the plot of House of the Rising Sun also drawn from your family history?

JLB: The plot of the book has two origins. There’s the story from the Old Testament of how Ishmael is cast out by Abraham because of the jealousy of his wife, Sarah, and there’s the legend of the Arthurian knight’s search for the Grail, which is symbolic of redemption. In other words, I’ve stolen both plots out of Judeo-Christian and Celtic legend. I’ve been stealing from the Bible for a long time! I’m always afraid I’m going to get in trouble down the pike—“We’ve been waiting for you! Are you the guy who’s been violating our copyright?” [Laughs.]

JS: You have deep family roots in both Texas and Louisiana, right?

JLB: William Burke, my paternal great-great-grandfather, was at Goliad with James Fannin, and in 1836 he left the state with his children and went to New Iberia [Louisiana] and bought land and became a sugar farmer. He died, let’s see, holy moly, in 1839 of yellow fever. My mother’s family came to Texas, most of them, in the 1850’s from Alabama. I think originally they had settled in the Carolinas and like many people who went to Texas, they migrated with one or two stops across the Deep South. You know the expression GTT, right?

JS: “Gone to Texas.”

JLB: Which meant “for reasons nobody wants to talk about!” [Laughs.] Jim Bowie came to Texas as an entrepreneur and adventurer, but he’d killed men in duels, and he was involved in the illegal slave trade with Jean Lafitte and Lafitte’s brother. That doesn’t mean he was less than brave—he had enormous courage; he was tubercular and a canon had fallen on him when it was being mounted on the wall at the Alamo and crushed his chest and he still wouldn’t go to the infirmary. He died, evidently, with both guns in his hands when the Mexicans broke in. He died a horrible death, and took two or three guys with him.

JS: You grew up in Houston when the city was segregated. As a child did you ever imagine that in your lifetime the city would elect a black man as mayor, reelect him twice, and then, a few years later, elect and twice reelect an openly gay woman as mayor?

JLB: I wasn’t in Houston when these events occurred. However, I have long felt that white people of good will and people of color would realize that we had a shared heritage, for good or bad, and that we have much in common. We still have a ways to go, but look at the progress we have made. I think the issues of race and gender will disappear before long, and in the meantime we live in a glorious nation, one that everyone wants to emulate.

JS: You’ve spent most of your adult life in Louisiana and Montana. Do you still think of yourself as a Texan?

JLB: Oh, Texas is a beautiful place. I loved growing up on the Gulf Coast and the stories I was told. My grandfather had a ranch in Yoakum, and I went to see him not long before his death. He was 94, and we were sitting in the gallery, and he was talking about the Sutton-Taylor feud back during Reconstruction, and he said, “Butch”—he always called me Butch—“look out yonder.” He was pointing at the dust, and he said, “These cowboys came here and they threw a rope on a boy, he was just a cowhand”—I forget if it was the Suttons or the Taylors—“and they dragged him up and down right here, in that dirt where I’m pointing at, and they shot him over a hundred times, they were so afraid of him.” He didn’t say they hated the boy—he said they were afraid of him, because that kind of depraved behavior always originates in fear.

My grandpa was a peaceful man. My father was too. He despised war, and he despised the rhetoric of those who lauded it. He lost his best friend on the last day of World War I—November 11, 1918. And I remember he would listen to people who were bellicose and he would always tell me, “They send young men off to war and thereby vicariously revise their own lives through the suffering of others.” My dad was quite a guy.

JS: You’ve written pretty much a book a year for the past thirty years. Is the next book already finished at this point?

JLB: No. It’s the third book of this trilogy. House of the Rising Sun is the second, Wayfaring Stranger is the first. And the third book is titled The Jealous Kind.

JS: Weldon Holland, a grandson of Hackberry Senior, is the protagonist of Wayfaring Stranger. Hackberry is the protagonist of House of the Rising Sun. Who’s the main character in The Jealous Kind?

JLB: Aaron Holland Broussard, another one of Hackberry Senior’s grandchildren.

JS: So each book has a different protagonist?

JLB: Yeah. This is the fact, Jeff: I had to wait over fifty years to write Wayfaring Stranger because there were too many people I didn’t want to hurt or invade their privacy.

JS: You were waiting for those people to pass on?

JLB: I didn’t think about it in those terms, but, yes, I couldn’t write about those things at the time. What’s the admonition of Hippocrates? “Do no harm.” Your art should always serve a higher purpose and do no harm. It’s a great experience to be an artist. This is the way I’ve always felt: the one area we share in common with God is creation; art allows us to dip our hand into infinity. We share in the province of god at that moment. That’s why I always feel humility is not a virtue for an artist or writer—it’s a necessity. The great enemy is vanity and ego. It destroys art, it destroys us. I’ve never seen a writer who uses the first person frequently who is not about to lose his talent. “Me,” “mine,” “myself”—all those words, they’re not good words. And when you hear a writer or artist taking credit for his work, he’s about to lose his gift. Every artist knows the gift comes from a hand outside themselves. That’s how it works, it comes from somewhere else.

- More About:

- Books