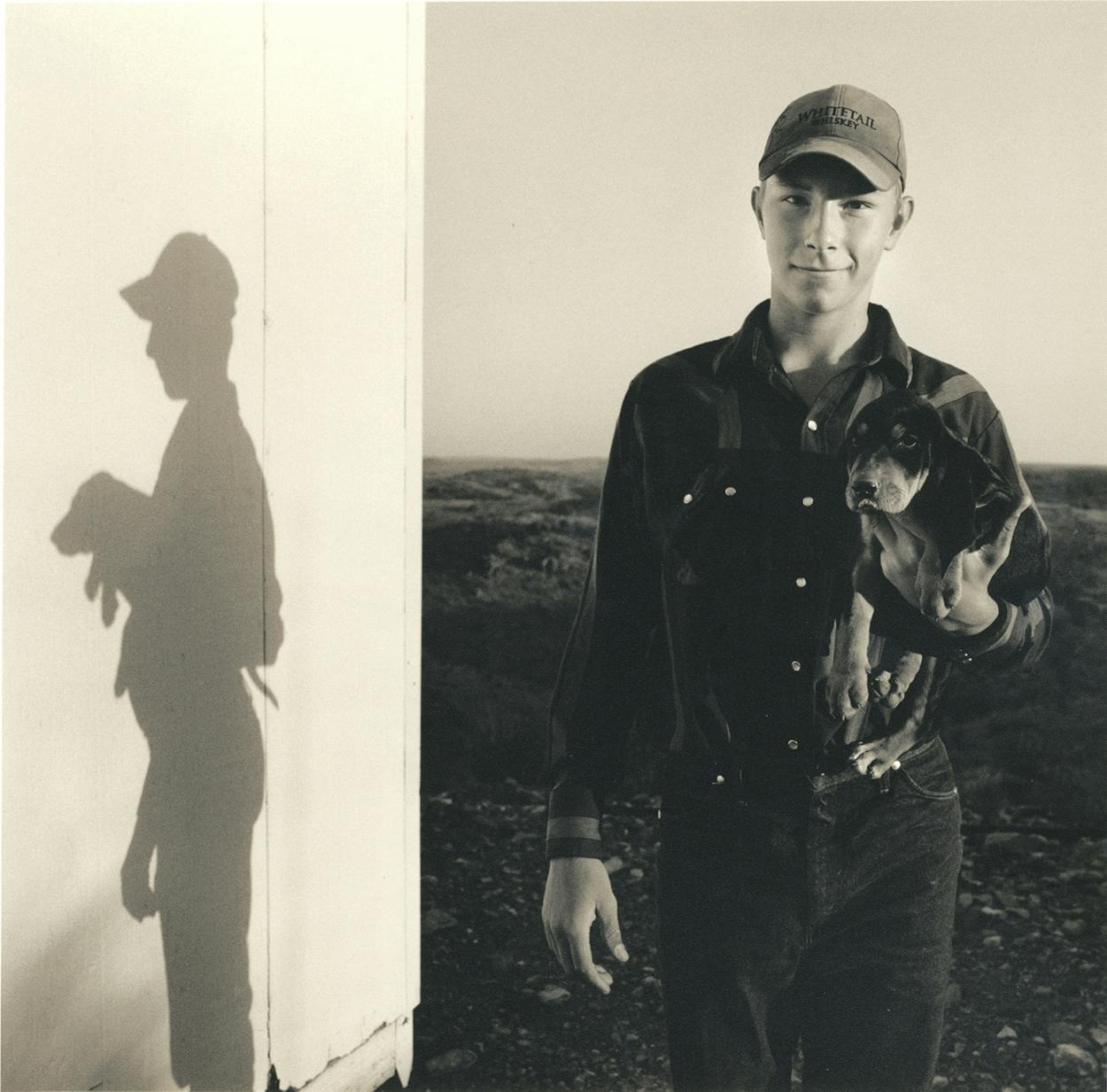

The sun is not yet up as June’s voice floats over the draws and craggy canyons of the Dipper Ranch. Her owner, fifteen-year-old Jasper Klein, sits on a gray mule and listens. June is the strike hound for the pack of hunting dogs Jasper runs with his brothers, thirteen-year-old Trevor and eleven-year-old Tanner. She is black, white, and tan, long-bodied and droop-eared. She moves over rocks in a loose, swinging trot with her nose skimming the earth, her white-tipped tail waving. The other hounds work the boulders at the base of the rocky hilltop where the boys wait. They are waiting for June to catch the scent of a mountain lion. “She’s looking,” says Tanner. “She’ll find it,” says Jasper. The dogs huff and their tongues loll. June bays every time she catches a whiff of the scent. Her bay is two syllables, the first note pitched lower than the second: aahh-oooo. And again: aahh-oooo. She sounds like a bell tolling.

Presidio County’s wilderness unfurls below. The Dipper is 50,000 tumbling acres, grass growing amid the towering rocks, ocotillo forests, stands of Thompson’s yucca, fields of catclaw, and occasional cottonwoods growing in creek beds. The wind groans in the saddle of the mountains.

The Klein boys run their dogs a couple of times a week, now that homeschooling is done for the summer. Their parents, Walter and Brenda, go along too. Although the whole family hunts, this is really Jasper’s passion. “I’ve always liked dogs, and I’ve always wanted to chase lions,” he says. “My main goal is to have a set of dogs that is really good.”

June’s baying grows more frequent. An old orange-and-white hound, Jewel, catches the scent too and yips. The dogs take hold and follow the scent up the mountainside until they meet a fence line. Jasper dismounts and hoists the dogs through a gap in the fence. They race to the mountaintop, tails held stiff and high. There’s no quarry in sight, but the erratic trail means they’re after a bobcat.

At the top of the peak, the boys and Walter park their mules, clamor around a cliff side with the dogs, and slip out of sight. Brenda waits with the mules. The mountain drops steeply to the left, the rock streaked with veins of dark red and black. Half an hour or more passes in the pleasant sunshine, punctuated occasionally by the sounds of the boys or Walter whooping to one another. Eventually they reappear.

“Well, the bobcat won today,” Walter says as he unties his mule. “There’s no scent on the bottom of a bobcat’s feet. If it gets on the rocks, it jumps from rock to rock and the dogs will lose the scent.”

Trevor and Tanner climb out of the canyon. Jasper whistles up his dogs.

“You lazy thing,” he scolds June, who gazes at him. He’s not truly mad, and the dog knows it. She smiles her dog smile at him and wags.

Brenda watches the exchange.

“This is what they’ll remember,” she says softly, pointing her mule toward home. “When I worry about schooling or the house or how we’re going to manage this or that little thing, I have to think that, really, I just have to be here with these boys, be present with them. Because this is what they’ll remember always.”

In the early years of their marriage, Walter and Brenda scrapped together a life in and around the Big Bend. He day-worked at ranches or welded or worked as a mechanic; she coached and taught at various schools. For a while, they both taught at a prison in Fort Stockton. When the boys were young, the family lived on a five-acre plot in Alpine, but Walter grew weary of his long hours in the mechanic’s shop, where he often stayed until midnight. Despite the heavy workload, the family’s financial pressures seemed to mount instead of subside. They longed to set their own schedule and to simplify. Seven years ago, an opportunity opened up to live at the Dipper, where they now look after the landowner’s property and cattle. They also run their own cattle on the ranch and pursue their own projects: hunting lions, for instance, or building a roping arena or raising colts. The nearest town is Marfa, forty minutes away. Moving to the Dipper changed everything. The family is together all day, every day. “We’re better off in this place than we have been in our whole lives,” Walter says.

The notion of living on a ruggedly beautiful ranch, dependent on no one but your own family, working with dogs and horses and cattle, is deeply alluring, a timeless idyll that is peculiarly Texan. The Kleins aren’t recluses who shun modernity—they’ve got cellphones and watch YouTube like anyone else—but there are long stretches of their days where the outside world and its trappings of technology and mechanization are simply absent, their time untouched by a morning commute, Facebook, Starbucks, deadlines. Riding out to gather cattle, the boys could be living in 1912 instead of 2012, their squeaking saddles making music as their horses long-trot to mama cows and calves in distant pastures.

Practically speaking, though, it’s also a hell of a lot of ceaseless, sweaty, difficult, and sometimes dangerous work. Mornings at the Dipper start about six o’clock. The boys head to the barn and kennels to feed horses, dogs, and chickens and return to the house for breakfast. During the school year, they study at the kitchen table, overseen by Brenda. She carefully pieces together curricula from different sources and drives the boys to Alpine or Marfa for tutoring, 4-H meetings, and soccer. School lasts for several hours every day, but this is flexible; if something comes up or Walter needs help, school is suspended temporarily. If the boys miss school during the week, they make up the time on the weekend.

In summer, the Klein boys run dogs or practice team roping while it’s still cool in the morning. Chores vary from day to day. The ranch’s remote water troughs, water lines, and livestock must be checked on a regular rotation. Cattle get into pastures where they’re not supposed to be. Colts need handling, and cows need doctoring. There are always fences to fix. The boys work side by side with their parents. They can do things most grown-ups can’t.

“They can drag calves in a pen, ear notch, castrate, vaccinate, brand, and sort cattle,” says Walter. “They’ve day-worked for a few people on outside ranches.”

“Everyone they’ve worked for says they’re real good hands,” adds Brenda. “The better they’re doing at school, the more they get to go.”

They started swinging ropes at age four and began riding solo at age four or five. Usually they rope calves or steers, but sometimes the situation gets more exotic.

“We roped a bobcat once and put it in a feed bag and brought it home,” says Jasper.

“We roped a badger once too, but we couldn’t get it into the feed bag,” Tanner adds. “It fought too hard.”

The boys can weld and shoot. They can each drive a stick shift.

“I had my first wreck when I was six,” Tanner says.

“He hit a cattle guard and dinged up the truck,” Walter explains. “It’s actually the only wreck they’ve had.”

The boys drive all over the ranch. One of their rides is an idiosyncratic, throaty-sounding Jeep, rigged as a hunting vehicle and dubbed the Purple People Eater. There are 473,000 miles on the odometer and a Playboy bunny logo on the gearshift.

“We didn’t put that on there,” Jasper clarifies. “It came with that.”

The Klein kids can change the oil, plug a flat, and change a tire. They can fix the float on a water trough; operate a front-end loader, a skid steer, or a bulldozer; hook up a bumper pull or a gooseneck trailer; gentle and start colts; two-step; identify grass species; and play chess.

Other things that one or two of them can do, to varying degrees: trim hooves and shoe horses, set traps and prepare hides, braid rawhide, do an around-the-world with a yo-yo, fish, guide hunts, make scrambled eggs, mimic an elk call, wiggle their ears.

They are athletically built, tall, and whip smart. They inherited their mother’s blond beauty and their father’s blue-eyed gaze. They always work in long-sleeved shirts. They are intensely curious, and they do not cuss. They bicker and sock one another but get over it quickly. They say “yes, ma’am.” There is a great deal of wrestling at the Dipper Ranch.

Trevor sits sleepily at the kitchen table early one morning. The moon still hangs in the sky.

“Have you combed your mop?” Walter booms while stirring sausage into the eggs on the stove. “Have you brushed your tooth?”

“That’s what Dad says every morning—‘brush your tooth,’ ” Trevor explains.

“You know how to compliment a girl from Mason?” Walter asks him brightly. “You tell her, ‘Nice tooth!’ ”

A few hours later, as the family returns from hunting, Walter and Brenda watch as the boys sprint ahead on their mules, chasing and dodging one another across the pasture. Their laughter comes back on the breeze.

Walter eyes Brenda. She probably knows what’s coming.

“That’s our kids for you,” he says with mock seriousness. “Just sitting on their asses.”

Along with the five humans who live on the Dipper, there are many animal residents. Tommy and Pup are Catahoula curs that go everywhere with the Kleins except inside the house. A mouse that Tanner discovered in some hay bales nestles in a shoebox in his room. Two striped, comically snorty feral hog piglets, captured by the boys at a water tank, now live in a pen by the barn. The barn is patrolled by three adult cats, two of whom just had litters. The eight hunting hounds—black-and-tan coonhounds, redticks, July hounds, and Treeing Walker hounds—howl from their kennel. There are two newborn fillies, five yearling colts, and five two-year-old colts that the boys are saddle breaking, plus some riding horses, mules, and broodmares. Cattle are scattered all over. A bull snake coils in a cage on the porch. Out in the henhouse, the Klein boys nuzzle and sweet-talk four velvety hound puppies.

“Aren’t they beautiful?” Tanner asks.

“A guy once told us that in life you have one great dog, one great horse, and one great wife,” says Trevor. “We already have some great dogs, and we’ve had some pretty great horses.” He pauses a moment. “I’m hoping maybe that guy was wrong.”

The boys say they don’t miss living in town, except for not being able to play baseball on a team. They’re not lonely. They don’t have television, an Xbox, or a PlayStation. They say they have what they want.

“I’d like to be a rancher when I’m older,” says Jasper. “And guide hunts professionally.”

“I’d like to ranch too,” Tanner agrees. “And ride bulls in the rodeo.”

“I’d like to run cows and ranch, but I’d like to train horses too,” Trevor says. “I’m going to be a bronc stomper.”

Walter and Brenda know that their boys aren’t growing up like other kids. That’s all right. “I read a quote that humans are herd animals and that if you’re in the herd, you act like the herd,” says Brenda. “We want to teach the kids to be independent, to lead and think for themselves. Here they can be who they are, instead of being everyone else. So much of life is learning to work things out.”

After lunch one day in June, the Klein boys load feed into the Purple People Eater and climb in. They are off to meet their loan officer and check on cattle along the way. Two years ago, when Jasper was thirteen, he took out a $5,000 loan from the Farm Service Agency and purchased seven heifers that were bred to a son of Houdini, a famous bucking bull.

“I’m interested in rodeo,” says Jasper, “but I wasn’t interested in getting hurt. It seemed like I could have a longer career providing the bulls for rodeo instead of riding the bulls. A top bucking bull can bring in a lot of money for its owner. So I bought these heifers to breed rough stock.”

The cows are ready to drop this year’s calves any day. In their first calf crop, the cows produced two bulls, which are now approaching two years old. Their bucking instinct will be tried out soon using a chute the boys built for a 4-H project.

“You open the chute and see if the bulls buck when they come out,” says Jasper. “We need to buy dummies to test on them.”

“For now, it’s me and Trevor,” says Tanner.

A year after Jasper’s FSA loan, Trevor got to thinking. He was eleven years old, and it was time to start his own cattle venture. He secured a $4,000 loan from the FSA and negotiated with an area rancher for five cow-calf Braford pairs, working for the rancher as part of the deal.

The three boys eventually formed a partnership—the 3K Cattle Company—whose holdings now include the rough stock, the Brafords, and sixteen other calves. The goal is to grow the herd to one hundred head.

“If they keep buying cattle and paying off their loans and keep building their herd, by the time they finish high school they could have a pretty good income and a pretty good start in life,” Walter says.

The boys bump the Jeep down the ranch road, making stops at isolated water tanks along the way. They check to make sure water is in each tank. Occasionally they whoop to draw cattle near and dash some feed onto the ground. An hour into the drive, at some cattle pens, they meet up with Brenda and the FSA officer, Ryne McKinney. There are handshakes all around. The loan officer does not look much older than Jasper.

The boys tour McKinney around the pastures, pointing out the rough-stock cattle and the Brafords, talking about feed and the need for rain. When the inspection is complete (“Looks good!” says McKinney), the boys deposit the loan officer back with their mother and continue driving down ranch roads, whooping to cattle, peering at troughs, and dumping out feed. The roads go on and on. Low-growing cacti and stalky cholla are in full magenta bloom. Dark blue clouds hover and spackle the ground with a few drops of rain. This is the middle of nowhere.

The boys look for a big black steer that’s in the wrong pasture. The clamor of the Purple People Eater’s engine makes conversation difficult, and the afternoon grows sleepy and long. They pull up at the house at six o’clock. They’ve fed forty cattle and been driving more than five hours. They will rest for a bit, eat, and then head to the barn. There are horses to shoe.

The next morning, the hounds leap around the mules as Walter and the boys head out again to hunt mountain lions. They are all briefly skylighted on the top of a rise before dipping out of sight. For the next hour, nothing is heard from them. June streaks alone over the spine of a hill and is gone in a flash. At one point, hoofbeats approach and Trevor materializes out of the whitethorn on his mule.

“We’re up here,” he says before submerging into the brush again. Distant whoops echo and roll through the canyons, then it’s quiet. The stillness seems very loud.

“We dropped off the mountain to the right,” Jasper reports later, back at the barn. “We went down a draw and saw a bunch of aoudad. June disappeared, and after a while we heard her baying. She had something treed—a lion. We got there, and there was nothing there. Our other two good dogs tracked to that tree, in and around and up the hill. It escaped from the tree to the rocks. And then it got too warm for the dogs to smell.”

The chase usually ends this way, with the quarry getting away. No one seems to mind.

His work over for the day, Trevor’s mule, Blondie, sighs as he’s unsaddled. Trevor has a new halter, and he slips it on the mule’s head after unbuckling the bridle.

“It’s sad, putting such a pretty halter on such a piece of junk,” he says. “Mules are always looking out for number one.”

“But they take you through rough country all the time,” Brenda points out. “They take you in and bring you back all in one piece.”

“They can go through anything,” Trevor agrees. “They can go up a mountain like a goat. But they’ll also try to run off with you or brush you off under a cedar tree.”

Blondie seems blandly unfazed by Trevor’s criticism. He joins the unsaddled mules in the pen, all looking for a place to lie down and roll. A red mule called Tiny delicately lowers his 1,400-pound self into the dust and heaves from side to side, grinding away the sweat. He grunts with effort. It is very hot. Cicadas whine.

“Let’s swim,” Tanner shouts.

Ten minutes later, the boys are in swim trunks at a round, rock water tank beneath a silvery windmill near the house. A couple of small trees partially shade a wooden deck around the tank. Iced tea is set out. T-Bone, a glossy black-and-tan coonhound, has somehow escaped being kenneled after the hunt. He slinks around apologetically at the base of the rock tank.

“I wish dogs could talk,” Jasper says. “I wish June could talk. She’d probably say, ‘Where have you all been?’ ”

Tommy, the Catahoula, runs around the edge of the tank, barking a frantic, choppy bark of joy. A turkey vulture wheels overhead. Lunch is soon. Although the sun shines strong, the boys know the water will be cold. They hang back for a few moments on the deck of the tank. Then the countdown: one, two, three, jump.