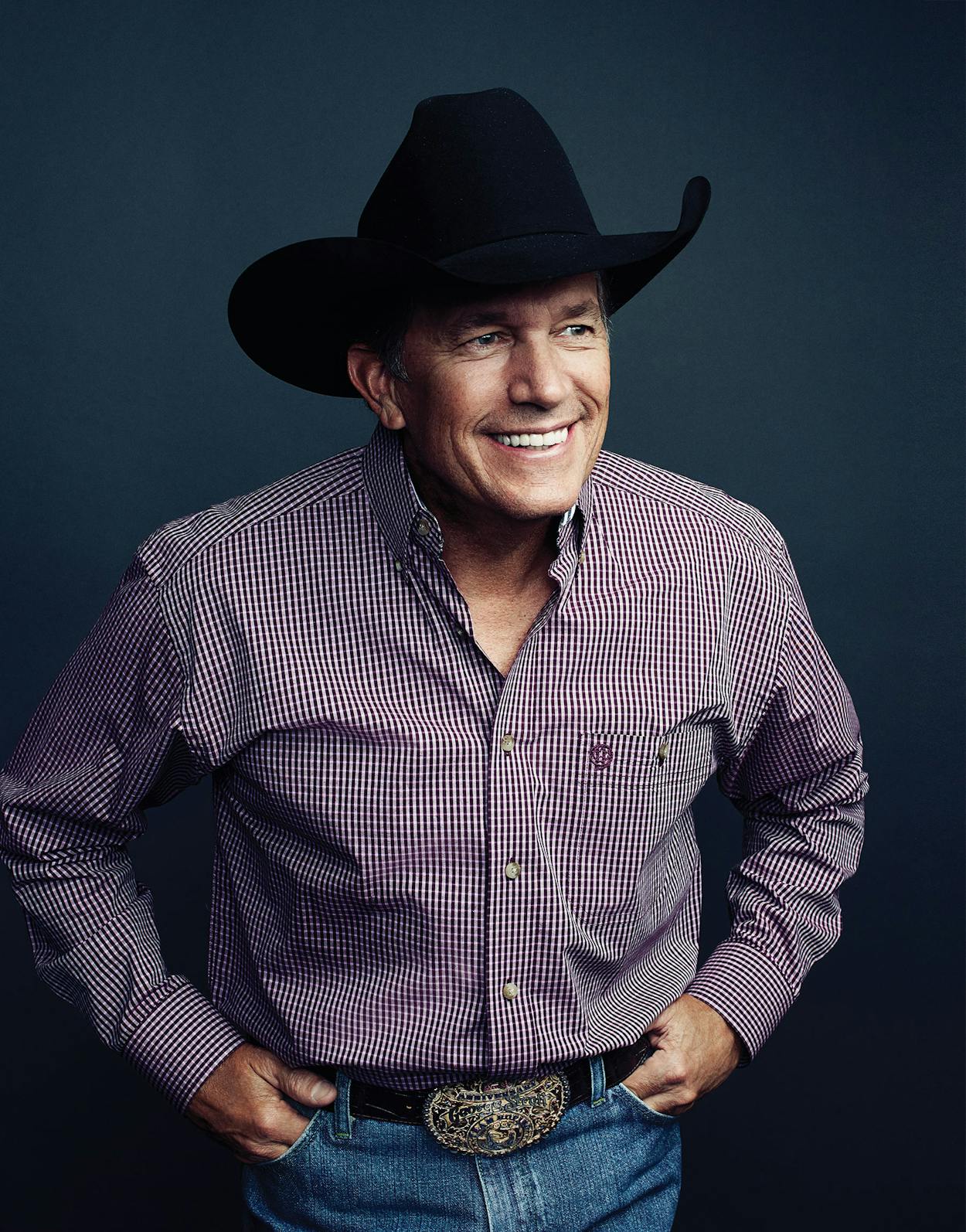

George Strait’s eyes are green, somewhere between the color of a Granny Smith apple and pool table felt. He’s got the bright-white, worry-free smile of a country club golf pro, somebody who makes his living flirting with older women. His face is quietly handsome and friendly, and he usually looks like he’s enjoying himself. His expression often suggests he’s open to a little mischief, nothing too dramatic, maybe a beer or two too many. He’ll always leave room to charm his way out of trouble. In truth, none of that is too terribly extraordinary. He probably reminds you of someone you had a crush on or looked up to in high school.

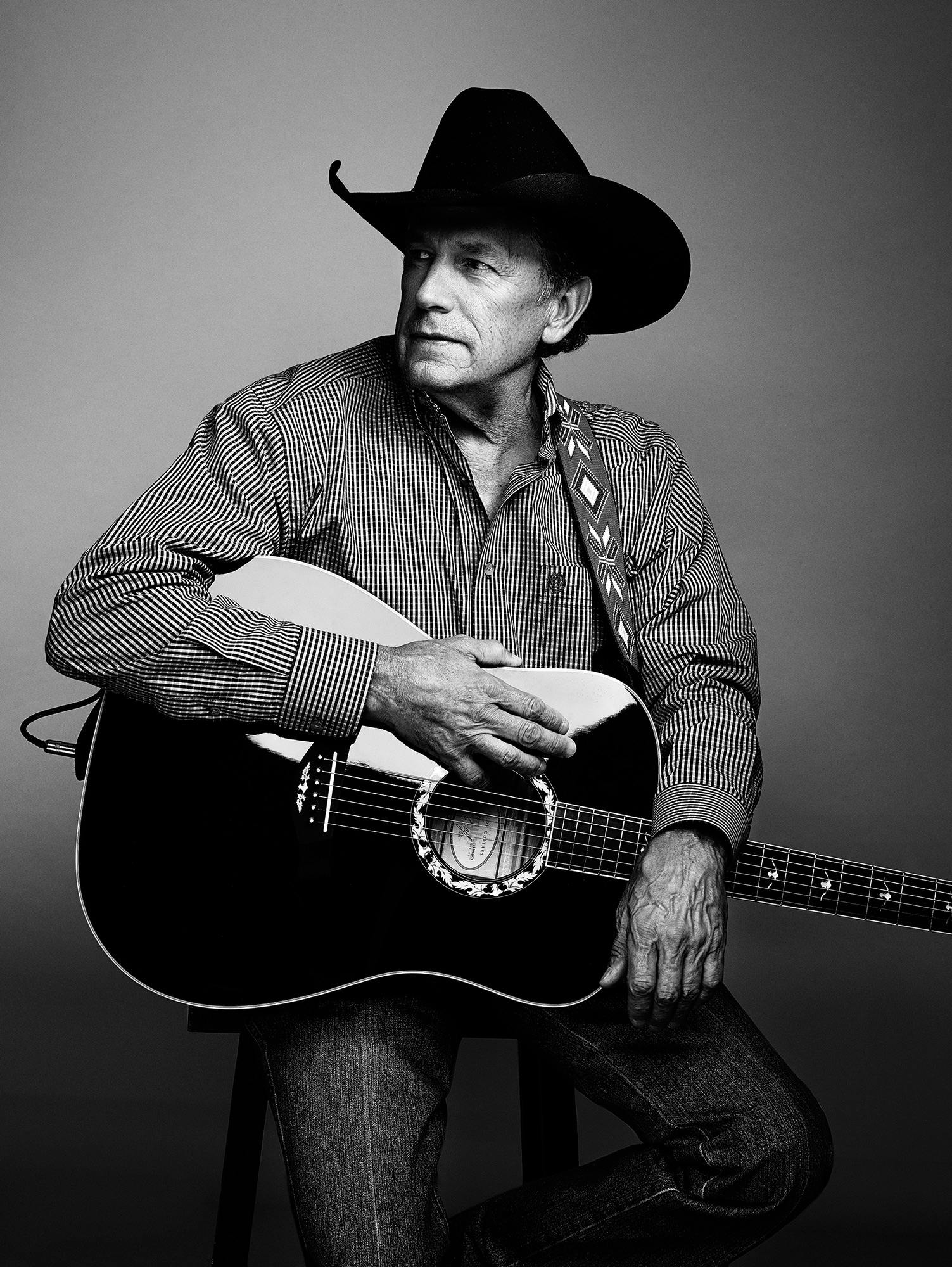

So move on to his music. In the 33 years he’s been a major-label recording artist, he’s released 28 studio albums, every one a collection of old-fashioned meat-and-potatoes country music. The songs are barroom weepers and cheaters, balanced with others about true love, family, and faith. He delivers them with a warm, expressive voice that is more comfortable than remarkable, keeping to the straightforward style of Merle Haggard rather than the vocal acrobatics of George Jones or the vibrato of Ray Price. The melodies are often poppy and sometimes they swing, but they always come dressed in fiddle and steel guitar.

That sound was distinctly out of favor when Strait started recording in 1981. As that decade wore on, he managed to pull traditional country music back into vogue, and he’s stuck with it through every trend that has surfaced in the meanwhile. Improbably, it has made him the most successful singles artist in history, owner of more number one songs than any other artist in any genre—44 on the Billboard country chart or, if you use his record label’s math, which adds in Mediabase’s measure of country radio airplay, an astounding 60 number ones. There’s no hyperbole in saying that his loyalty to the old sound is the single most important reason it stayed alive and on the radio.

Those qualities and accomplishments make comparisons to other artists difficult. All of Strait’s hits were on the country charts. He never enjoyed the pop-crossover success of Garth Brooks or Taylor Swift, or the music snob credibility of Willie Nelson or Johnny Cash. If you expand the parameters outside the country world, a different problem arises. Bruce Springsteen and Jimmy Buffett are both as closely associated with a place and sound as Strait is with Texas and country. But New Jersey gearheads and beach-loving parrotheads consider Springsteen and Buffett their poets. Though Strait had one songwriting credit on his second album, he only recently resumed writing. Strait is first and foremost a vocalist.

The comparison should be, then, to another pure singer, and there’s a temptation to think of Strait as our Sinatra. In certain ways the reference is apt. Both built long careers interpreting other people’s songs. Each man’s instrument was his voice, and the artistry was in locating the emotion in someone else’s words and communicating it believably. But there’s a key distinction in the way listeners connect with their music. Frank Sinatra made his audience come to him, and the world in fact knew him as Mr. Sinatra. Strait, on the other hand, may be King George to the press, but fans know him simply as George. He seems to actually be a part of the crowd that loves him. Sinatra’s career gets broken into periods, like his early swooning-bobby-soxer years, his post–Ava Gardner alone-in-a-bar years, and the later-in-life Chairman of the Board years. Strait’s career can’t be divided that way. Viewed as a whole, his catalog is monolithic, and that’s a compliment. It is one big, rock-solid block. His fans supply the shadings—Right or Wrong was the only cassette in the pickup on a spring break trip to the beach; Ocean Front Property played nonstop in the dorm during sophomore year in college; Livin’ It Up was a solace during a divorce; Carrying Your Love With Me was the go-to CD for rocking a firstborn to sleep.

So maybe the place to start with Strait is at his concerts, where the songs roll out of his Ace in the Hole Band, one after another, for two and a half hours. None of his fans come expecting surprises. All of them know how a George Strait show goes. The stage will be a square in the center of the arena, with a mike at each corner for Strait to sing into. First the band will come on and kick into “Deep in the Heart of Texas,” with Strait waiting in the wings. Then he’ll walk out, wave to the crowd, slip on his guitar, stand at a mike, and sing. No choreography will follow, no elaborate video show, no fireworks, no jumping around. Strait won’t do one thing to distract from the songs. And fans will respond as if he’s singing about their own lives.

Which explains why those same fans greeted the September 2012 announcement that Strait would be retiring from touring like they would the news that the family dog had to be put down. The Cowboy Rides Away Tour, which began on January 18, 2013, in Lubbock and will end this month, on June 7, in Arlington, is being billed as his last as a regular touring performer. For Strait it’s been a seventeen-month, 48-date victory lap around the United States. But it’s been something different for his audience. He’s promised to continue releasing new music and playing occasional one-off concerts. But for fans, many of whom grew up attending a Strait show every couple of years, the Cowboy Rides Away Tour represents the last chance they’ll likely ever have to see him play live.

In January of this year, 18,000 of them filled the Sprint Center, in Kansas City, Missouri; and as a longtime fan myself, I was among them. Tickets had been snapped up in less than an hour when they went on sale last October, and on show night, the crowd endured a brutally cold wind in an hour-long line to enter the arena, then taped homemade banners to the mezzanine guardrails once they got inside. My seat was halfway up from the floor, next to a young couple who’d driven in from Ohio. While we waited for Strait, they gushed about the previous night’s show, in Omaha, which they’d also attended. Then they bragged about their tickets to the tour’s grand finale, in Arlington.

When the music started, attendees in the high-dollar seats found empty parcels of arena floor in which to two-step and waltz. Each time Strait took to a new corner of the stage, fans flooded the aisles leading down to that spot, and each time he moved on, they looked heartbroken, as though they were genuinely afraid he’d never come back. They giggled when he sang “Check Yes or No,” hollered when he sang “Here for a Good Time,” and cried when he sang “I Saw God Today.” When he sang “How ’Bout Them Cowgirls,” the arena video screen showed pretty female faces in the crowd, and none of those women even noticed they were on camera. They had forgotten about the monitor. They were transfixed by Strait.

And throughout the night’s performance, through the long torrent of applause and tears, through the constant cell-phone camera flashes and cries of “We love you!” “Come back to Kansas City!” and “George! George! George!” over and over, all Strait did was stand there and sing. Just like he’s done since the beginning.

In the spring of 1981, when MCA Records was preparing to release Strait’s first single, “Unwound,” there was no reason to suppose people would still be listening to him 33 years on. This was the era that country fans of a certain age deride as the “urban cowboy” period. The term, however, is a misnomer. Though the John Travolta movie that inspired it made unlikely national figures out of middling singers Johnny Lee and Mickey Gilley, Urban Cowboy merely capitalized on the sound that already dominated Nashville: watered-down, wide-appeal country. The artists who’d perfected it, singers like Kenny Rogers and Eddie Rabbitt, were selling millions of records by shucking steel guitar and fiddle for a sound so unobjectionable it would have put Jim Reeves to sleep with his head in Chet Atkins’s lap. Throughout these years, Nashville was looking past the country chart. The real money was on the pop and adult-contemporary charts. And since country artists had a more realistic shot at the latter, the better name for this period comes from the AC chart’s original identifier—this was Nashville’s Easy Listening era. If you loved hard-core country, it was a dark age. To paraphrase Voltaire, as any meaty discussion of country music should, had there been no George Strait, it would have been necessary to invent him.

If someone had, however, they almost certainly wouldn’t have drawn up a calf roper from Poteet fronting a western swing band. But that’s what 28-year-old George Harvey Strait was: a recent ag grad of Southwest Texas State supporting his pregnant high-school-sweetheart wife and their ten-year-old daughter by working cattle during the day and playing music at night. He and his band, Ace in the Hole, were a huge draw on the Texas dance-hall circuit, which was precisely their limitation in the minds of country A&R reps, even those nostalgic for a traditional sound. Nashville country had originally come down from the mountains. It was hillbilly music, ballads and banjos. Texas country was something else. It was waltzes and shuffles and above all western swing, the upbeat jazz-and-country hybrid that Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys had used to introduce the Grand Ole Opry to the revolutionary notion of drums—to which it came kicking and screaming. Western swing was dance music, and George Strait and Ace in the Hole were a dance band. They would not have had a harder time selling themselves on Music Row playing reggae.

There was also the matter of Strait’s appearance. He was sure enough a good-looking guy, but he wore a cowboy hat, an accessory that, for Nashville, had effectively died in the backseat of Hank Williams’s Cadillac. He also wore plain brown boots with a low roper’s heel and Wrangler jeans, starched and stacked, meaning they were left extra-long so they didn’t ride too high up his leg when he rode a horse. Simply put, he was a South Texas cowboy and he looked it, which was not a package that a country record label could hope to cross over to pop with. When Strait made occasional trips to Nashville to shop for a record deal in the late seventies, the labels all passed. He wasn’t too country, he was too Texas. They did allow, though, that he had a nice voice. It was suggested he could make decent money singing demos.

And then Erv Woolsey stepped in. In the early eighties Woolsey was the head of promotion at MCA’s country division, the person in charge of getting performers’ records on the radio. But he was also a Houston native, and he had been working with Strait since he’d booked Ace in the Hole in a San Marcos nightclub he owned during a mid-seventies sabbatical from Nashville. Now that he was back at the seat of power, Woolsey paired an unsigned Strait with an untested producer, Blake Mevis, who softened his Texas edge without dulling him completely. As they readied to record, Mevis scrounged for songs and found a demo of “Unwound.” He played it for Strait and Woolsey. The singer wasn’t sure the song fit him, but Woolsey heard a hit and convinced him to cut it. MCA execs gave it a listen and immediately signed Strait to his first record deal.

“Unwound” was released on April 23. If you’d heard it on the radio that day, it might have been preceded by a song like Kenny Rogers’s “Lady,” a Lionel Richie–penned–and–produced thimbleful of syrup that had recently spent six weeks as a pop number one. As Rogers’s raspy voice faded out—“You’re the love of my life, you’re my lady”—and the song came to an end with a polite cymbal rush and tinkling piano, a hard fiddle line would have suddenly stormed through the speakers, six stomping beats flying up into a flurry of high-whining notes before giving way to Strait’s solid baritone. “Give me a bottle of your very best,” he sings, “ ’cause I’ve got a problem I’m gonna drink off my chest.” Accented by a chiming pedal steel, “Unwound” expressed a familiar lament: the singer had cheated, gotten caught, and been kicked out of his house. Or more specifically, “that woman that I had wrapped around my finger just a’come unwound,” which sounded familiar only if your memory was long enough. This was country of the fifties roadhouse variety. One can only wonder what unfortunate song the deejay would have played next. Maybe Juice Newton’s “Angel of the Morning,” at that point lolling through a three-week stint atop the AC chart.

In the coming months, “Unwound” worked its way to number six on the country chart, and when the two subsequent singles off his perfectly titled debut album, Strait Country, went top twenty as well, Strait found himself at the forefront of a budding market correction on Music Row. Nashville session musicians noted how refreshing it was to record with him and play real country music. Soon enough, critics would start calling Strait, bluegrass picker Ricky Skaggs, and fellow honky-tonker John Anderson the “new traditionalists.” But Strait felt his recordings were still too contemporary. He wanted to pull his music deeper into an old Texas sound. Mevis’s only nod to swing on Strait Country had been to borrow the intro to Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood” for that opening to “Unwound.” After Mevis tacked a recorded seagull’s call to “Marina del Rey,” a song on Strait’s second album, Strait From the Heart, Strait hired a San Antonian, Ray Baker, to produce his third record. The significance of a fellow Texan at the helm was clear from the album’s title, Right or Wrong. The title track was an old Bob Wills barn burner that would become one of three number ones off the record. But that success was owed in large part to Woolsey’s promotional team. There were still wide pockets of the U.S. where Strait wasn’t getting played, least of all when he released a western swing single. In Nashville, a programmer at storied WSM, the station that invented the Grand Ole Opry, flatly refused to play “Right or Wrong,” explaining to Woolsey, “We don’t play that music.”

That was 1984. If you were a country fan in Texas at the time, the idea that there might be any resistance to George Strait was unimaginable. I was a junior at Austin’s Westlake High School back then, and as far as I could tell, Strait was everywhere. His image hung at the boot store and in record shops, his music played over the PA between innings at baseball games and blared out of pickup trucks in the parking lot after school. There was a good-looking cashier at the grocery store who never asked for an ID when I tried to buy beer, chiefly because I always asked to see the backstage snapshot of her and Strait that she seemed to carry at all times. Then my friends and I would drive to vacant lots, drink the beer on open tailgates, and listen to George (the fact that his first name indicated “Strait” and not “Jones” proved he’d already crossed a key threshold for us). He had the exact appeal that Nashville execs always claim to be looking for: girls wanted to be with him, and guys wanted to be like him. One by one my friends and I made the leap from Levi’s and Tony Lamas to Wranglers and Justin ropers.

Still, I had only modest expectations the first time I went to see him play. It was at the Austin rodeo in March 1985. I’d been to such shows before and knew the routine. Once the bull riding ended, a tractor would pull a stage to the middle of the arena. Then the night’s performer would be driven in, waving awkwardly from the bed of a pickup while trying not to spill out of the truck and onto the dirt. And there was a lot of that dirt between the audience and the stage. The ensuing thirty-minute set was almost always a letdown.

Strait’s set was different. He rode into the arena on horseback, bringing a roar from the crowd that didn’t subside when he took the bandstand. As he led Ace in the Hole through his early hits, the aisles filled with two-steppers and the noise grew louder and higher in pitch. With the intro to each song, whole sections of the audience seemed to be overrun by shrieking women. Finally, he started into “You Look So Good in Love,” and at the beginning of the spoken second verse, a dam burst. Presumably he wasn’t mouthing the words—“Darling, I’ve wasted a lot of years not seeing the real you”—but there was no way to know. The crowd was so loud you couldn’t hear him at all. As the song wound down, I remember thinking that the show was the rodeo-cowboy equivalent of the Beatles at Shea Stadium. It was country music as cultural phenomenon.

Or at least it was in Texas. Late that summer Strait put out a fifth album, Something Special. I learned about it while driving through town one Monday night, working my pizza-delivery job, when a deejay at KVET promised to play “George Strait’s new album!” in its entirety through the course of the evening. That was unheard of—country album releases weren’t considered events the way rock records were—and in fact, deejays outside Texas didn’t give Something Special the same treatment. The rest of the country had yet to catch on.

The album’s lead single changed that. Set in a dance hall, “The Chair” opened with a slurred steel-guitar line but then moved in an unexpected direction. It contained no chorus. The lyrics were clever and conversational, one side of an awkward come-on and invitation to dance: “Could I drink you a buy? / Oh, listen to me, what I mean is . . .” Paired with tight shots of Strait looking sheepish in the song’s video (a marketing tool that Strait had previously tried to avoid), “The Chair” was irresistible to female fans, geography notwithstanding. They may not have lived in regions where people danced to country music, but they sure wanted to dance with Strait, and radio programmers in every corner of the U.S. took note. “The Chair” kicked off a four-year run of thirteen consecutive top five hits for Strait. Or rather, twelve number ones with a straggler that made it only to number four. Strait was as big as anybody in country music.

It’s said that if you don’t have an ego when you get to Nashville, they’ll give you one. Strait avoided that by choosing never to live there, which has kept him away from industry politics and silly concerns like “Why does Taylor have more billboards than me?” He’s so disinclined to music business nonsense that he’s never even accepted the Opry’s standing invite to join; membership would require more time in Nashville than he’s willing to spend. Instead, he splits his downtime between San Antonio, Rockport, and his ranch outside Big Wells.

His point man in Nashville is Woolsey, who left MCA to concentrate on managing Strait in 1984. He runs the empire from an unassuming house one block off Music Row, a two-story gray brick that could stand a few new shingles and a new coat of paint. The reception area is the front porch, glassed in with the Saltillo-tile floor left in place, and the way into the office proper is through the old front door, still flanked by exterior house lamps and the doorbell. The scene lines up nicely with Strait’s understated image, but also with Woolsey’s reputed penchant for thrift and affection for the word “no.” Woolsey doesn’t even list his cell number on his business card. He says it’s because he hasn’t gotten new cards printed in a while. It is just as likely that he’s cutting out an extra step in turning people down.

Woolsey is a master of rejection. “George’s first major award was for male vocalist of the year from the Academy of Country Music in 1984,” he told me, sitting at a big desk in a converted bedroom that smelled of cologne and whiskey. “They said they didn’t have room for him to perform on the broadcast, so we signed on to do a fishing show down in the Caribbean. Two days before the awards, Dick Clark called and said George had to be there, had to sit on the front row. I said, ‘Let me get this straight. He’s not good enough to perform, but you can’t do the show without him in the audience?’ I said, ‘No, we won’t be there.’ ”

Woolsey looks a little like Kenny Rogers, with white hair and a trim white beard. But he dresses like Strait, in creased jeans and a button-down shirt from Wrangler’s George Strait Collection that he leaves untucked over a healthy paunch. His friends teasingly call him “the Colonel,” after Elvis Presley’s puppet master, Colonel Tom Parker. No one implies that Woolsey actually tells Strait what to do, but they know him as a cagey old radio man who’s directed the singer with a clear strategy of record, tour, promote, and repeat. “We were always fair to radio, always visited every station in each city. Back then he was playing one hundred and seventy shows a year, and the key was just getting those people to see him. Once they saw the crowd reaction and him signing all those boots and hats—it was amazing—those deejays would say, ‘I’m adding this record.’ It just kept building and building.”

And then a funny thing happened. Nashville is weird. It fights tooth and nail against change until somebody has success trying something new, at which point the whole industry starts doing that thing. Strait’s old producer Mevis likens it to a bunch of people looking over the side of a boat, then deciding the view must be prettier on the other side and all rushing over at once. “When George started hitting,” said Woolsey, “every label wanted a hat act. It still fascinates me. MCA had told me, ‘He’s got to get rid of the hat.’ Now entertainers who’d never worn a hat would put one on as soon as they got here. They didn’t know a good one from a bad one. I’ve seen them put them on backwards.”

The shift was so sudden and complete as to be comical, and “hat act” soon became a derogatory term. Strait managed to avoid being lumped in with the bunch. He wasn’t of it, he’d invented it. But the trend soon posed another problem. Some of the artists who followed Strait’s lead had real talent. In 1989 and 1990 Clint Black, Garth Brooks, and Alan Jackson each debuted with hugely successful records. A new generation was pushing older acts off the airwaves, and Strait’s own sales took a noticeable dip. MCA execs started worrying that his run might be over.

Whether Strait’s next step was in reaction to these concerns is hard to say. Woolsey calls it good timing. But in 1991 the singer who didn’t like appearing in videos agreed to star in a movie. The story line of Pure Country is not complicated. Strait plays a country star who has lost his sense of self, who’s been pushed by unseen forces to do such un-Strait-like things as grow a ponytail and fill his live shows with pyrotechnics. Fed up, he abandons his concert tour. He gets a haircut and hides out on a ranch, passing his days roping calves, strumming guitars, and falling for a barrel racer. To reveal that he then triumphantly retakes the stage to play his songs his way does not require a spoiler alert. But the film also contains a wonderfully backhanded subplot: the tour goes on in his absence, with a member of his road crew impersonating him in concert. In other words, watch closely, country fans, because Nashville will let anyone who can carry a guitar get onstage.

Released in late 1992, Pure Country was a box-office dog. But it has had a remarkable afterlife on cable and video, and the sound track has become the best-selling album of Strait’s career. “We sold seven million records on that,” said Woolsey. “And then there was the power of that movie. It holds the record for the most home video sales on a movie that didn’t do $25 million gross at the theaters. You can still see it for sale in Walmart.” Through the rest of the decade, Strait kept plugging away, releasing roughly an album a year, each of which sold two or three million copies, plus a box set, in 1995, that sold eight million. Meanwhile, Clint Black disappeared and Garth Brooks got so big (see No Fences and Ropin’ the Wind) that all he could do was implode (see Chris Gaines).

“Some stars lose touch with reality,” said Woolsey. “I think they’ve been told yes so many times that they don’t know the difference.” But Woolsey brushed aside the question of whether he was thinking of Brooks’s astonishingly bad decision to create a gothed-out alter ego. Country people don’t publicly slag their own. “Garth has been a huge influence on country music. A monster. At the ceremony when Garth got into the Hall of Fame, George sang ‘Much Too Young (to Feel This Damn Old).’ That was real good.”

Tony Brown tells a great story about Strait. Brown has produced every Strait album since Pure Country. They typically go into the studio in the spring and early summer because it fits Strait’s touring, hunting, and rodeo schedules. They used to record in Nashville studios like Emerald and Ocean Way, but beginning with 2006’s It Just Comes Natural, they shifted to Key West. Jimmy Buffett has a studio there that Strait likes to use. It’s a small, white, windowless cinder-block box that sits on the water by some boat slips. Strait sails his yacht, Day Money, down for the sessions, ties up outside, and lives on the boat through a week of recording.

“Nashville studios have nice lobbies with couches and a TV and a big spread of food to make everybody comfortable,” says Brown. “Buffett’s is not that way. There’s no place to hang out. But George likes it. So one time the guys were fixing a guitar or something, and George goes outside and sits in a chair. He’s got a baseball hat on and is all slouched down, and Erv and I are standing there. This older couple walks down the boardwalk. The lady goes, ‘Sir, my husband says George Strait is in that building cutting a record.’ And George says, ‘Honey, I was just in there, and I didn’t see him.’ So they walk off. George says to me, ‘It’s so good to be famous.’ I said, ‘What if they’d recognized you?’ He just smiles and says, ‘They never do.’ ”

That’s Strait’s appeal in a nutshell: he’s normal. He’s handsome, but not shockingly so (apparently, for two fans in Florida, he’s not even as handsome as George Strait). He knows how much he means to people, but that doesn’t drive what he does. His charm doesn’t grow from his ego. For years he’s avoided the press, turning down countless requests for interviews, talk show appearances, and TV-special star turns (for this story, he would agree only to answer questions by email). The lower profile suits the way he wants to live. His fans know the rough outline of his personal life—that he’s been married to his wife, Norma, for 42 years, that his daughter, Jenifer, died in a car accident when she was just 13, that he recently started writing songs with his 33-year-old son, Bubba, and that he’s leaving the road to spend more time with his first grandson, 2-year-old George Harvey Strait III—but they don’t need to know any more than that. Strait keeps a gap between his home and the stage, and his audience respects it.

As a business strategy, that’s been a smart way to extend his career. Media exposure may drive sales, but it also builds expectations and inevitably fades. Strait’s never faced that. He’s never had a song or album top the year-end charts, but he’s also never quit hitting. If you ask anyone in the industry to explain that success, they’ll offer a one-word answer: songs.

It’s not the obvious response it might seem. As Robert K. Oermann, the dean of country music journalists, explains, “The Nashville Songwriters Association has a slogan: ‘It all begins with a song.’ That’s the truth. In pop, a beat can be enough. It’s not in country music. A riff is not enough. A country song has to tell a story, it has to make someone feel something. In no other genre on the radio is the craftsmanship of the song so important.” The description is earnest but accurate. It’s why Nashville still conducts business the old-fashioned way, with writers composing songs that publishers pitch to artists. The talent for matching singers with songs and correctly predicting hits is its own job description on Music Row.

Strait may have the best ear for a hit in the history of country music. That’s the distinction you earn when you release 94 singles over a 33-year period, and fully 84 of them reach the Billboard top ten. He’s been picking songs himself since his fourth album, 1984’s Does Fort Worth Ever Cross Your Mind, when he was finally well enough established to start co-producing. Most stars get that power near that stage in their careers. That’s also the point where many start to decline.

“George has never thought he was bigger than the songs,” says Sonny Throckmorton, who co-wrote “The Cowboy Rides Away,” which Strait took to number five in 1985. “A lot of singers get that big response onstage and start thinking they can do anything. But if you cut a bad song, that’s like a gut wound. You’re hurt and don’t know it until your career is dead. It doesn’t matter how big you are. God couldn’t have a hit on a bad song. George knows that.”

For much of Strait’s career, he’s been the only singer who could reliably top the charts with a honky-tonk song. This meant that anytime someone wrote one, they’d send it to him. His go-to writers, like Dean Dillon and Jim Lauderdale, will tell you he made their careers. For every other songwriter, getting a Strait cut became the holy grail. Whenever he books studio time, all of Nashville starts buzzing, with songwriters angling to get songs in front of him. Strait listens to hundreds in the weeks before recording. He plays them for Norma to get her reaction. He keeps listening to demos at night after the sessions start. Almost every album has contained at least one song that came in over the transom while he was recording.

But still, he has to sing them. Even in that he’s been guided by deference to the song itself. Every songwriter with a Strait cut I talked to commented with equal parts pride and appreciation on how closely his vocals tracked their demo. When MCA started getting polished singers to recut Dillon’s demos, Strait demanded they give him Dillon’s originals. He needed to hear what Dillon had meant. “If you stay close to what Whitey Shafer intended when he wrote ‘Does Fort Worth Ever Cross Your Mind,’ ” says Throckmorton, “you’ll wind up with something pretty good. Strait’s smart enough to do that. He trusts the songwriter.”

Woolsey and the rest of Strait’s organization are adamant that the Cowboy Rides Away Tour is not a final farewell. Strait may be giving up touring, but he will definitely continue recording. In fact, when I met with Brown in February, the producer was already trying to find studio time for Strait’s next sessions and talking about new songs he wanted him to hear. For his part, Strait has joked with friends that if the cowboy can ride away, he can always ride back in again.

But changes may be at hand. Country music is in a strange place. The best-selling female artist, Taylor Swift, is essentially a pop star. And the music that the male artists are putting out all sounds the same. It’s dominated by thundering drums and hard-rock guitars and young-buck singers in ball caps. They sing—or really, they rap, and not well—about driving pickups to backwoods keg parties and hooking up with girls in Daisy Dukes. You’ll hear the style labeled as “bro country” or “hick-hop,” terms spat out with the same disgust “urban cowboy” once inspired. Country music needs George Strait every bit as badly as it did in 1981. But back then, most radio stations were owned by individuals, and all Woolsey had to do to get Strait on the air was get program directors to attend his concerts. Now those stations are owned by conglomerates like Clear Channel and Cumulus, and the people at the top of those pyramids have decided to stick with this new sound. Sometimes country radio seems like one long, loud song.

Last year Strait released two singles. One was “I Got a Car,” a story song written by Tom Douglas and Keith Gattis that follows a marriage from first date to first born. It peaked at number 28. The other was “I Believe,” a ballad that Strait wrote with Bubba and Dean Dillon. It was inspired by the Newtown shootings, and in it Strait sings about relying on faith to live through the loss of a child. It was the first single of Strait’s career that didn’t make the top forty. Country radio simply would not play it. “With all these party songs out there,” said Brown, “you start to understand why certain songs aren’t working on radio. It’s hard to follow ‘Get your sugar shaker over here’ with ‘I Believe.’ ”

The lapse may prove a mere hiccup. But it might be something more. At some point Strait’s inevitability will end, the hits will no longer be guaranteed. Once that happens, he can stop chasing them. He can start taking chances. He won’t likely record duets with Snoop Dogg or Jack White, like Willie Nelson and Loretta Lynn did, or edgy rock covers, like Johnny Cash. But things could get interesting. “I told him to consider doing a concept record,” said Brown. “Or let’s go to Capitol Studios, in L.A., and hire an arranger to cut a big-band record like Sinatra. If there are no rules anymore, and he doesn’t decide to cut just his own songs, he can cut a western swing record. Or do “George’s Favorite Songs,” by guys like Earl Thomas Conley, Marty Robbins, and Mel Street. I don’t like thinking that it might finally be time that he becomes ‘a legend.’ But think about what Linda Ronstadt did. She made those Mexican records. And those Nelson Riddle records. Those were big records.”

For now, though, it’s more likely that Strait will continue on as he always has. He’s never been more than a song away from another number one. And if Woolsey is still relying on his old strategy of giving radio programmers an eyewitness look at Strait’s connection with his audience, he’ll have the ideal opportunity on June 7, in Arlington. One hundred and nine thousand Strait fans will fill AT&T Stadium that night, for a performance that promises to be the single biggest event country music has ever seen. If the Clear Channel power brokers pay any attention at all, they’ll find ample evidence that Strait is still relevant to the lives of country fans.

I say this with confidence because I know what that relationship looks like. The Kansas City show in January wasn’t the only one I attended on the Cowboy Rides Away Tour. A week earlier I went to his last Austin show, and I took my wife, Julie. We’d realized our shared taste for Strait shortly before we married three years ago, when I stored my old vinyl with her CD box set. We like to listen to him while we make dinner together. Invariably I ramble about high school and college until Julie starts talking about when she first became a fan. It was in the early nineties. She’d just moved home to Texas after four years studying dance in Ohio and was struggling to let go of her dream of being a big-city ballerina. She listened to a lot of George Strait during that time. Her favorite song was “Easy Come, Easy Go.”

He sang that song early in his set when we saw him in Austin, and I looked over at her about halfway through it. She had a smile on her face that I’d never seen before. For an instant, she looked like she’d forgotten I was even there. The song had taken her back in time, and I realized this was the closest I’d ever come to seeing her as a young girl. It was a wonderful moment. And all Strait did to give it to us was stand there and sing.

- More About:

- Music

- Longreads

- Country Music

- George Strait