Last year, the Dallas-based pop culture archivist Bri Malandro declared—alongside a repost of King Kong magazine’s Western-themed cover shoot featuring the singer Ciara—that “the yee haw agenda is in full effect.” The prophetic tweet caught fire, cementing a name for the surge of progressive Southern, country, and cowboy styles crossing from the fringe (no pun intended) into the mainstream. Soon “yeehaw” had seemingly flooded all corners of pop culture: In early 2019, homegrown country star Kacey Musgraves’s Golden Hour received a Grammy Award for Album of the Year, and yodeling teen Mason Ramsey had become an internet sensation. Social media—not to mention countless pieces revolving around the changing face of country music—brimmed with ten-gallon hats, rhinestones, denim, and chaps.

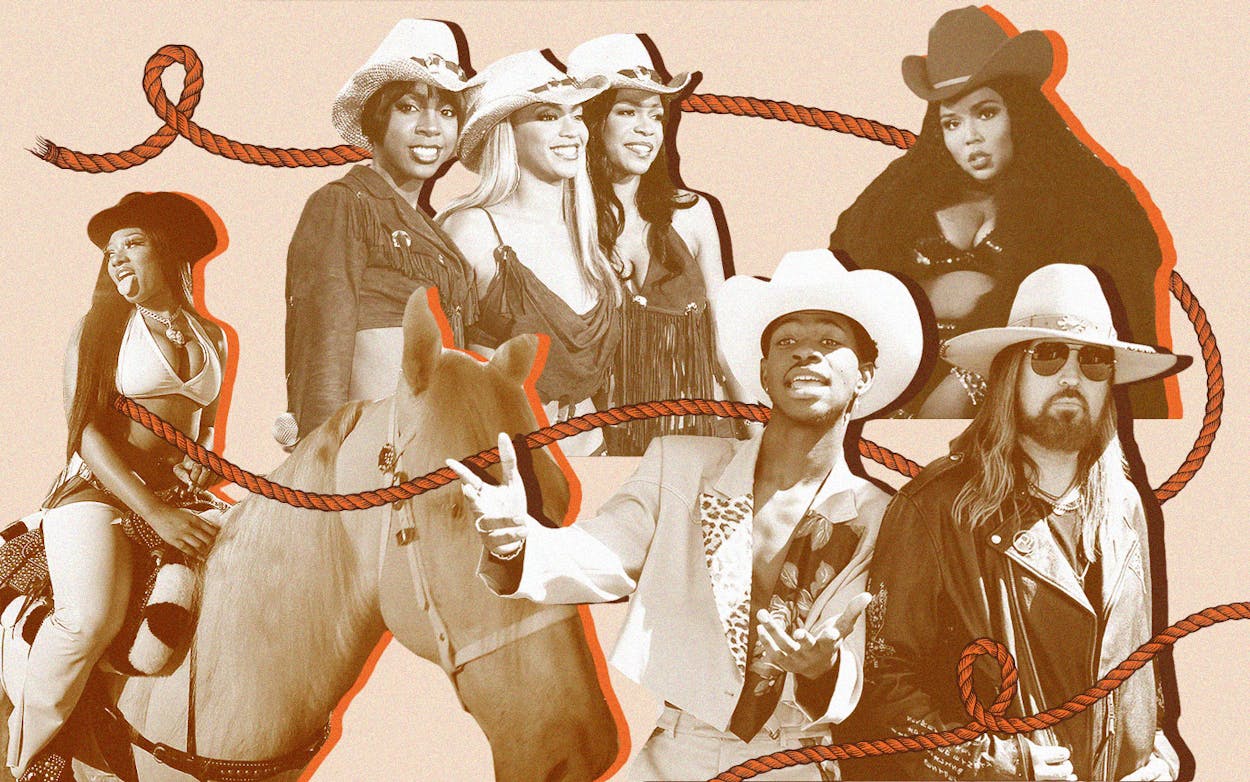

But Malandro’s comment, like the work she’d done documenting pop culture for nearly ten years on the internet, zeroed in specifically on the way black folks have been embracing and pioneering nontraditional country style long before now. Her popular Instagram account @theyeehawagenda chronicles decades of cowboy and Western-themed looks worn by people of color, including Texan royals Beyoncé and Solange, in addition to Prince, Mariah Carey, and her own favorite, Sisqó. More recently, this legacy has come to include Houston’s own rising rap queens Lizzo and Megan Thee Stallion, as well as Atlanta rapper Lil Nas X, whose genre-defying “Old Town Road” became the longest-running number one song in Billboard history this summer.

“The primary goal was to create an archive for the culture—I wasn’t sure who I’d reach, but it’s something I’ve always enjoyed,” Malandro explains over email. “I knew about mainstream country, but I also knew about Bone Thugs-N-Harmony making a song called ‘Ghetto Cowboy’ in 1998. I knew Westernwear always had a place in hip-hop and R&B fashion because I was a huge fan of Sisqó, Mary J. Blige, and Destiny’s Child. A lot of people don’t have the range to look past certain stereotypes—that’s never been a problem for me.”

It’s precisely this stereotypical conflation of cowboy culture and whiteness that’s made the POC-driven yeehaw agenda both so fascinating and so vital. Malandro told Jezebel this year that she’d coined the term “for fun,” noting that it was “just about the aesthetic.” But for many, that aesthetic is inherently political—at once propagating and subverting traditional country culture. Consider how at the height of cattle ranching, one in four cowboys was black. Yet a figure like Lil Nas X causes confusion and controversy today. It raises the question: in Trump’s America, can an internet-born pop culture movement infiltrate our notion of country ephemera to make it more honest and inclusive?

Systematic whitewashing of American history is nothing new. It enabled the cultural theft that’s kept black chefs from benefiting from the trendiness of Southern and soul food, erased the slave roots of square dancing, and, of course, extends toward contemporary music. It stretches even toward the hallowed mythology of cowboys. To wit: the word “buckaroo” is a bastardization of “vaquero.”

The American cowboy can be traced back to antebellum-era Texas. In 1821, English-speaking settlers led by Stephen F. Austin migrated to what was still Mexican territory, where land-owning caballeros and their hired vaqueros had been rounding up Texas longhorns for more than two centuries. Newly arrived Anglo residents adopted not only their cattle-ranching techniques, but also the culture that came with them. By the end of the Civil War in 1865, a third of cowboys were vaqueros and roughly a quarter were black, often freed slaves.

“Despite the fact that black people, Mexicans, and Native Americans made up a large portion of American cowboys, they were erased from history—never to be included in Western movies or history books,” says Alexander-Julian Gibbson, a Houston-born writer and visual artist. “It’s an unsettling truth considering that cowboys, especially when you grow up in Texas, are your first American heroes. They are the epitome of classic Americana, and to have black cowboys erased from that culture creates underlying tones that we aren’t a part of American history other than being slaves, when we absolutely were.”

It’s worth acknowledging that the true origin story of the cowboy doesn’t discount the role of white folks who risked their lives doing dangerous work that shaped the western frontier. But the erasure of cowboys of color sends a message that some Americans aren’t welcome to claim or find common ground within that particular culture.

Malandro credits her family for exposing her to black cowboy culture early on. Her father, Issiac Holt, played for the Dallas Cowboys, and she “saw a fair share of boots and hats in the house” growing up. But anyone who grew up in Texas knows that side of the story isn’t readily taught in schools. To learn about black history, one needs to look beyond classrooms to organizations like Rosenberg’s The Black Cowboy Museum or Dallas’s Texas Black Invitational Rodeo.

Perhaps most well-known among these institutions is the Bill Pickett Invitational, a national tour celebrating black cowboys and cowgirls. Gibbson, who covered this year’s event for GQ, says it’s integral not only to recognize the entire heritage, but also to continue passing that knowledge on. This is one way to contextualize the current yeehaw movement within its longer history, too. “The rodeo celebrates four generations of black cowboys—you can see cowboys and cowgirls as old as 77 and as young as two,” he says. “But the most important thing to rodeogoers, riders, and coordinators is that these traditions are passed down to the younger generation.”

Read about Myrtis Dightman, the “Jackie Robinson of Rodeo,” here.

While black cowboys have always existed and black artists have long employed Westernwear, it’s largely young people—armed with the knowledge they’ve culled from the internet—who are behind today’s rise of the yeehaw agenda. Malandro says the closest thing to a starting point for the current yeehaw movement might have been the release of Beyoncé’s album Lemonade. “She had a song on the album called ‘Daddy Lessons’ that she actually ended up remixing with the Dixie Chicks and performing at the Country Music Awards,” Malandro recalls of the controversial performance. “That was a pretty big deal; I remember seeing a lot of memes about that particular moment.”

While Beyoncé and the Dixie Chicks’ twangy collaboration was a live performance, it immediately evolved into meme-able, shareable, and clickable buzz—partly in response to right-wing backlash on Facebook pages and internet comment sections—that underscored its cultural significance. The record-breaking virality of Beyoncé’s visual album Lemonade, with its themes of black empowerment and reclamation of her Houston roots, gave way to a massive discourse online, too. Beyoncé walked so Lil Nas X could fly.

“The internet and social media have allowed for an almost infinite number of voices to flourish, including those who were never really offered a seat at the table before now,” explains Sandra Song, a cultural critic who writes a PAPER column called “Internet Explorer.” “For all of its faults, social media has acted as the great equalizer of culture in a lot of ways, as it provides ample space for differing perspectives and further discourse that most likely would’ve been brushed aside by more traditional media streams.”

To that end, today’s yeehaw agenda goes beyond reclaiming the status of black cowboys—they also create space for other people of color as well as queer folks. In Song’s analysis of the movement, she cites the work of writer Antwaun Sargent, whose viral Twitter thread about “chic and thriving” black yeehaw figures earlier this year presented many people with their first visible representation of “cowboys” that were both gay and black. And five months later, during World Pride, Lil Nas X came out.

With such built-in intersectionality, one might see yeehaw as a form of modern-day “camp”—complete with humor, theatricality, and a sense of self-aware irony—that uses fashion to question and disrupt conventional ideas about race and even sexuality. “Yeehaw encapsulates a lot of the tenets we hold dear as Americans—freedom, autonomy, and independence—unfortunately, it’s historically been the purview of white cis men,” Song says. “Rewriting this narrative is the first step in a long process of undoing the dominance and ubiquity of whiteness within American media. Add that to the fact that we’re currently being inundated by white supremacist rhetoric, and the reestablishment of QTPOC as the movers and shakers of culture becomes an important way to help stem the ‘othering’ rhetoric these hate groups thrive off of.”

Given the constant churn of trends and movements on the internet, yeehaw’s novelty may soon wear off (though the staying power of “Old Town Road” continues to surprise). Its lasting impact, however, will be the message of empowerment it’s bestowed upon young folks of color all over America, particularly in places like Texas. “I truly believe the lasting legacy of yeehaw will be the example it sets in terms of our ability to rewrite, reinterpret, and reclaim the cultural institutions that people have previously been excluded and erased from,” Song says. “But not only that: I think this movement will have a hand in the way we retrospectively examine Trump’s impact—or, rather, the rejection of his vision of ‘America’—upon American culture at large.”

Despite the vitriolic, turbulent nature of American politics, young Texans have much to look forward to in a state that’s rapidly changing. Houston, the fourth-largest city in America, was not only the first major American city to elect an openly gay mayor; it’s also now the most ethnically diverse city in America. And politicians like Beto O’Rourke, who inspired triple-digit growth in young voters and voters of color in 2018, are redefining how we’re seen on a national stage.

And if nothing else, yeehaw in music has come full circle. Driven by forward-thinking entertainers and artists, the movement’s popularity has now enabled them to lean even further into their Texas roots while making game-changing new art. Just look at Kacey Musgraves’ provocative reimagination of the country genre, Solange’s unabashedly proud love letter to her home state in When I Get Home, or Lizzo’s “Tempo” video—in which she goes full country camp in a blue feather boa and red cowboy hat.

“For a long time people expected only one type of person to come out of Texas and I think these celebrities, as unique and creative as they each are, have used their Texas pride to disrupt the narrative of the state,” Gibbson says. “Yes, we occasionally ride horses, eat a ton of BBQ, and love the rodeo, but there’s so much more.”

For Malandro’s part, what started as a fun archiving project has spiraled into a full-fledged movement. And while she may be a bit amused by how far things have gone—she recently trademarked “yeehaw agenda” in order to prevent it from being stolen—Malandro says she hopes the movement will help redefine Texas and the South in a “forward-thinking” way. “I can’t wait to see what the next generation does after growing up with Lil Nas X being the first cowboy they’re familiar with,” she says.

- More About:

- Music

- Cowboys

- Megan Thee Stallion

- Lizzo

- Beyoncé