With the school year quickly approaching, the Texas Legislature has provided a temporary fix to a statewide problem in public schools. In June, Governor Greg Abbott signed into law a bill that allows for a grace period for students who have insufficient funds in their lunch accounts, which advocates hope will end a practice they call “lunch shaming.”

SB 1566, which addresses the power of the boards of trustees at independent school districts, will go into effect on September 1. Representative Helen Giddings submitted the grace period as an amendment—her last attempt to end lunch shaming after the conservative House Freedom Caucus killed her bill on the issue in May. Under the amendment, students will be able to continue purchasing regular meals on credit during a grace period, with the length determined by the school’s board of trustees. Giddings’s amendment also prevents districts from charging a fee or interest for meals purchased during the grace period.

Lunch shaming, or school policies calling attention to students without enough money to pay for a regular lunch, has been in practice across the nation for years. But the issue made headlines in April when a picture of a child’s arm stamped with the words “LUNCH MONEY”—meant to indicate that the student didn’t have enough funds in his account—went viral. Tara Chavez, who took the picture after her son’s arm was stamped by a staff member at his Phoenix, Arizona, elementary school, told BuzzFeed that she usually received a slip when her son’s account was low. “He was screaming and crying the entire time,” Chavez told BuzzFeed. “He was humiliated, didn’t even want me to take a picture of it.”

Students can have low funds in a school lunch account for a range of reasons: if a family makes too much income to qualify for reduced lunch but too little to comfortably afford the meals, if parents haven’t filled out necessary paperwork, if a family emergency has prevented parents from depositing funds. When families can’t (or don’t) pay, school districts often have to absorb the debt into their budgets. A study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture found that 58 percent of “local educational agencies” had unpaid meal debts during the 2010-2011 school year.

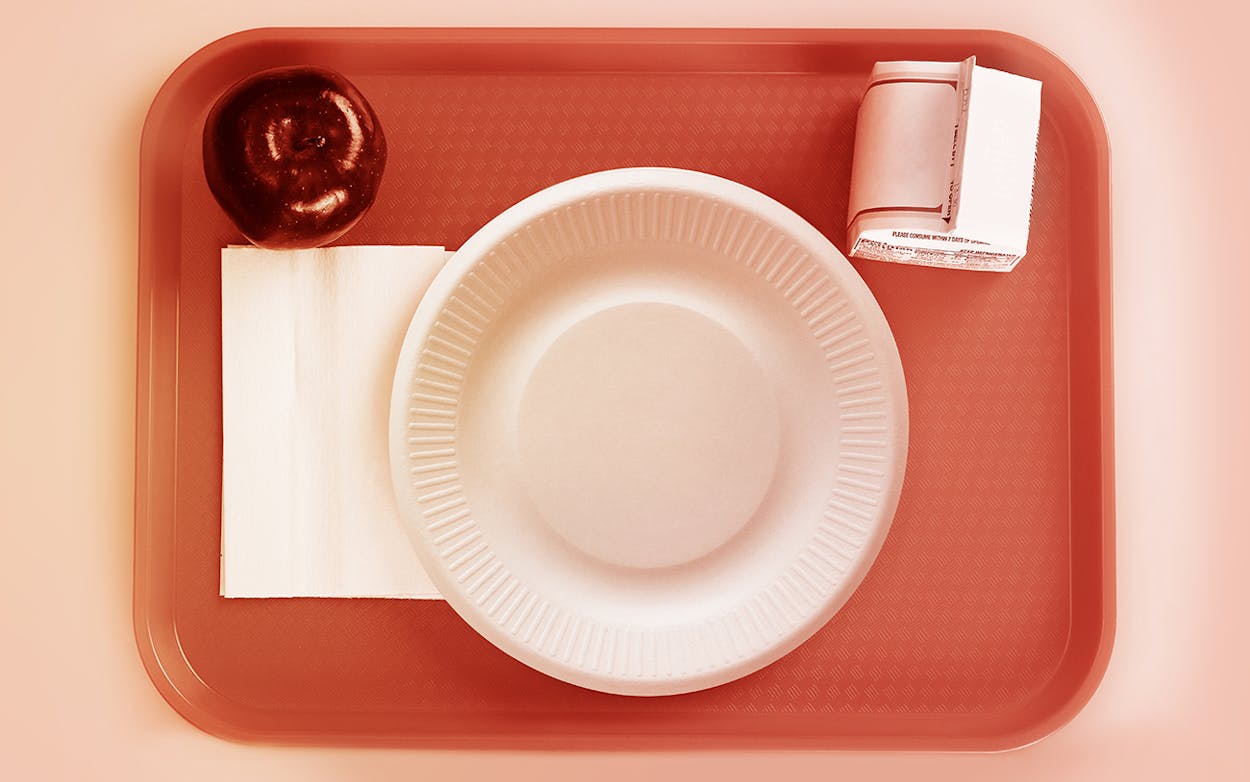

Policies penalizing a student for insufficient funds vary across school districts. In some schools, students with school lunch debts must clean up the cafeteria. Texas school districts don’t stamp students, as in Phoenix, but at some schools, students who can’t pay for their regular lunches have them thrown away—sometimes in front of their peers—and are given alternative free lunches such as sandwiches.

Giddings’s original bill, HB 2159, would have required schools to give students with insufficient funds a grace period lasting at least two weeks, in which they could continue to receive regular meals. During that period, the school would also be required to make at least three attempts to contact parents about low funds. Another part of the bill requires schools to make an attempt to avoid pointing out a student’s inability to pay in front of classmates, which was not addressed in the final amendment:

A school district may not publicly identify a student with a negative balance on a meal card or account, and must implement any action authorized under this section in a manner that does not stigmatize a student or cause embarrassment. The district’s policy must identify the manner in which the district will prevent stigmatizing a student or causing embarrassment.

Members of the Freedom Caucus, who blocked Giddings’s bill in May, said it would result in an expensive mandate for school districts. Their opposition caused some contentious moments in the legislature—particularly between Giddings and Representative Jonathan Stickland—and things were still awkward when Giddings introduced her amendment in May. Stickland opened his remarks on the amendment by asking, “Representative Giddings, this thing that you’re working on here trying to put on has been pretty contentious so far this session, has it not?” To which Giddings responded, “It has been. Primarily by you, sir.” Giddings’s amendment was approved by the House on May 24, approved by the Senate—along with other House amendments—on May 27, and the bill was signed into law by Governor Abbott on June 15.

In addition to the amendment, Giddings also partnered with Feeding Texas, a nonprofit network of food banks, launching a donation page to pay for debts in student lunch accounts. In June, Giddings announced that the organization had raised more than $216,900 with the help of donations from companies such as HEB, Walmart, and Uber.

This isn’t the first crowd-funding campaign to tackle student lunch debts: In April, Austin residents raised more than $18,000 to pay off meal costs in the Austin Independent School District. Still, donations aren’t a permanent answer to food insecurity. As Addie Broyles noted in the Austin American-Statesman, crowdfunding is a “short-term solution” to a never ending problem. But the Austin donations meant that 3,500 students had their lunch debt wiped clean, Broyles wrote, and according to the Dallas Examiner, the funds raised from Giddings’s partnership with Feeding Texas will help provide more than 66,000 lunches to students in Texas. As food insecurity continues to be a problem that school districts tackle around the state—and the nation—Giddings’s amendment will work to make sure that Texas students aren’t shamed in the lunch line.