On Monday, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals partially lifted a judge’s order blocking Senate Bill 4, otherwise known as the sanctuary city bill. But as the New Orleans court discussed the legality of Texas’s immigration enforcement law, many of the state’s 1.6 million unauthorized immigrants are fighting against it closer to home. This includes a group of domestic workers in San Antonio who already face significant challenges in the workplace, some fearing that the law will enable police officers to stop drivers based on their physical appearance. “This law will destroy us all. They are going to point at us because of our racial profile, and they are going to stop us and deport us,” says Araceli Herrera.

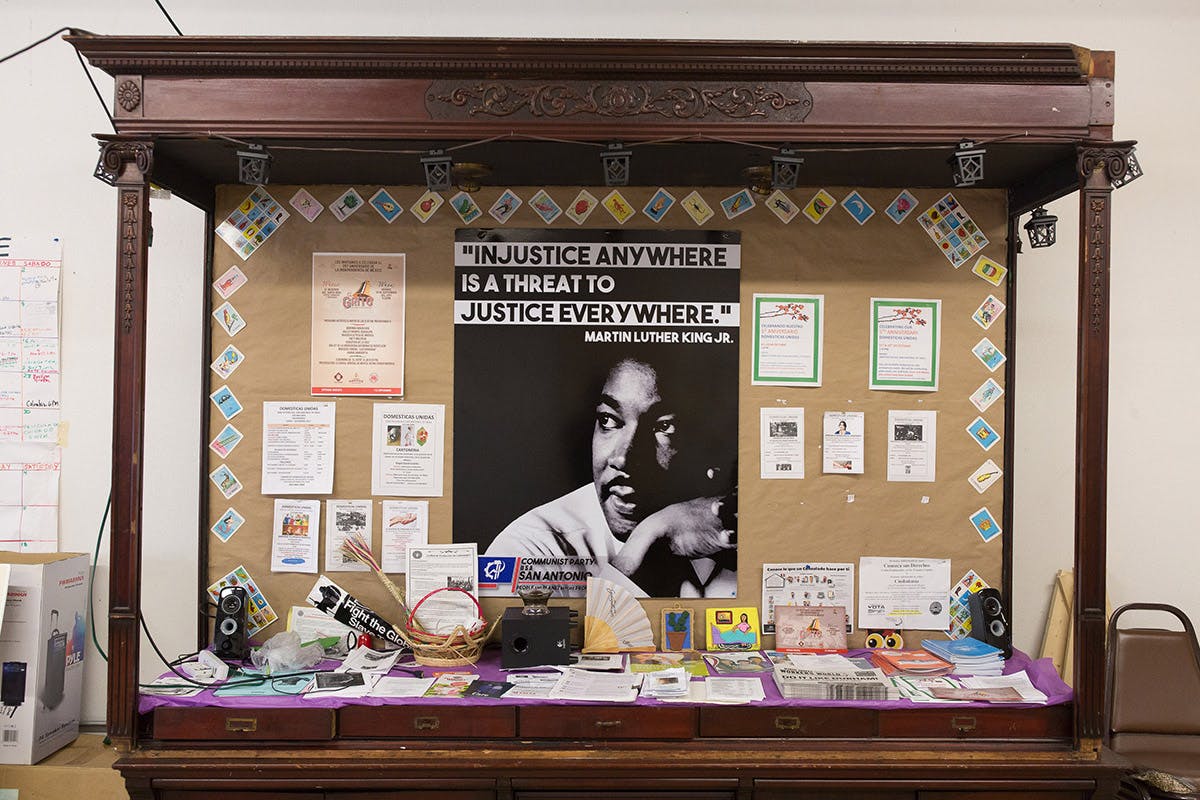

Herrera, 57, cleans houses in the San Antonio area, and was undocumented for many years. She’s also the founder of Domésticas Unidas, a sisterhood of mostly undocumented domestic workers in San Antonio that looks to boost the self-esteem of its members and offers workshops to improve their working conditions. The group will soon commemorate their tenth anniversary, though SB 4 has put their celebrations on hold. The sole thought of being separated from their families has them on edge, adding extra weight on backs that already take on the cleaning, cooking, and babysitting of well-off American citizens.

The group first formed because of a shared a common bond: Their commute. Before they called themselves Domésticas Unidas, many of the group’s present and former members used VIA’s bus route 97 in San Antonio. “There are many routes, but this one was special because we would engage in conversation in that bus,” Herrera says. The women chatted, sold Salvadoran pupusas, and brought cakes on each other’s birthdays. When one of them would get sick and couldn’t get to work, the rest of the domésticas, as they call themselves, would collect money and hand it in an envelope to the affected colleague. If one of them, or a relative, died, they would rally to offer financial support to the mourning family. “We have a beautiful sisterhood,” Herrera says.

In 2003, route 97 was suspended. Because their livelihood depended on it, they organized, protested, and met with VIA Metropolitan Transit representatives to bring it back to circulation. To Herrera’s surprise, the agency responded in December of the same year by adding another route to the affected area. In 2007, the domésticas’ route was restored. “It means that we have power,” Herrera says. For many domestic workers, it was the first time they had ever organized to advocate on their behalf. Now, the group’s motto is “cooking, cleaning, organizing and fighting, the world changes.”

Domésticas Unidas has held multiple educational workshops on SB 4 since the start of 2017, much like they did when defending the DACA and DAPA programs during President Obama’s administration. And the judge’s injunction against SB 4 has not altered the domésticas’ plans. They’ve marched in San Antonio, and joined others to protest the law at the Texas State Capitol in Austin.

But even after nine months of educational campaigns and protests in San Antonio, Austin, and elsewhere, Herrera notes they are always asked the same question by undocumented workers: What do I do if the police stops me while driving? “We find so many people that still have no idea what [SB 4] is,” Herrera explains. “Many don’t want to know how SB 4 will hurt them because they are scared. They go with their little kids and open their eyes when their questions are answered.” When stopped by the police, Domésticas Unidas recommends unauthorized immigrants in Texas to memorize the phone number of their lawyer.

Domésticas Unidas also offers its members workshops on how to negotiate a contract, proper care of kids and the elderly, and human trafficking. New members, often coming from rural areas in Central America, also learn how to use modern washing machines and about the proper use of cleaning products and chemicals to prevent irreversible damage to their respiratory system and skin. They also meet to celebrate their diverse cultures and heritage, to share their home countries’ stories of independence, and even to practice yoga.

SB 4 is particularly threatening to undocumented domestic workers in Texas, where non-naturalized domestic workers represent 59 percent of all live-in maids or housekeepers and 26 percent of all live-in nannies, according to a 2013 Economic Policy Institute report. In contrast, 47 percent of live-in maids and 24 percent of live-in nannies in U.S. were non-naturalized. Live-in domestics, whose primary residence is in the home of their employer, are the most vulnerable to abuse and exploitation, according Herrera, who liked them to “slaves” in some instances.

The profession is often underpaid, offering less than minimum wage. “They are almost universally excluded from labor laws and usually work without a contract or any kind of agreement, written or oral, with their employers,” writes journalist and activist Dr. Barbara Ehrenreich in “Home Economics: The Invisible and Unregulated World of Domestic Work.” The 2012 survey of more than 2,000 nannies, caregivers, and housecleaners in 14 metropolitan areas in the U.S. found that 36 percent were undocumented immigrants, and that 85 percent of undocumented immigrants who encountered problems with their working conditions did not complain because “they feared their immigration status would be used against them.” Among all domestic workers, 23 percent were being paid below the state’s minimum wage. The research was made by several groups advocating for rights of domestic workers, including the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA), where Domésticas Unidas is one of the 60 plus affiliates.

According to the same 2012 report, domestic workers are not protected by common institutional federal labor and employment laws and standards. The National Labor Relations Act, which guarantees workers’ rights to form unions, choose representatives, and bargain collectively, excludes domestic workers. Other federal laws, like the Fair Labor Standards Act, which regulates minimum wage, explicitly excludes live-in domestic workers and other types of domestic workers from certain provisions, like overtime pay, though the FLSA and the Texas Minimum Wage Act do provide minimum wage protections to all domestic care workers.

Other federal laws indirectly exclude many domestic workers. Title VII, which prohibits discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, and the Americans with Disabilities Act only apply to employers that have 15 employees or more, offering no protection to domestic workers employed by a single household.

To address this lack of protection, some states have adopted a Bill of Rights for domestic workers. In New York, for example, the Bill of Rights says that all domestic workers have a right to overtime pay and a day of rest. But not in Texas. Additionally, employers of domestic workers do not have to report to the Texas Department of Insurance work-related injuries, occupational illnesses, and fatalities that occur in the workplace.

Herrara believes that long-term bonds with a family also enables employers to manipulate domestic workers into being constantly on call, often without being paid accordingly. Vanesa Ramírez, 48, has been available for her employer’s three girls day and night for the past fifteen years. Despite holding degrees in business administration and accounting, the undocumented Nicaraguan woman gets paid $550 per week for tasks that range from cleaning a five-bedroom house to, at times, assuming the role of a parent. “The girls call me at midnight saying, ‘Vanesa, my dad forgot to pick me up.’ So I race to pick them up,” she says. “I want to do it because I want the girls to be OK. Because they treat me like I’m part of their family.” Once she was the first one to get to the hospital after one of the girls burned herself at a friend’s house. (She reached the girl’s parents later that night.) Ramírez’s employer pays for her cellphone, and even served as a sponsor for her son to come to Texas. Still, he expects her to be on call at almost any time of the day. “I think they make us feel as family but the reality is that we are workers,” Ramírez says. Like many undocumented workers, Ramírez never signed a contract or agreement and her specific duties were never discussed when hired, so she feels she has no ground to draw the line about what her job entails.

The uncertainty of her work status, especially driving while undocumented, has brought stress to Ramírez’s family. “My kids ask me, ‘Mom, what are we going to do? Don’t work, stay at home.’ But I tell them we have to go out because hiding won’t solve our problems,” she says. Ramírez compares her current situation with her experience when the government of Nicaragua murdered her father during the Sandinista revolution that toppled the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza. “For a long time we could not say who we were children of. It’s the same anguish to say I don’t have papers.”

Andrea Osorio, 43, has been working as a domestic worker almost nonstop since she arrived in San Antonio when she was fourteen years old. Although she is still undocumented, she goes to rallies every time she is able to, bringing her three sons to show them what’s affecting their community. “I’m not scared and I have to do something to change this,” Osorio explains.

Osorio cleans twelve houses per week, and like many domestic workers, she must drive to reach all of them, even though Texas has not issued driver’s licenses to undocumented individuals since 2011. “We can’t prevent feeling scared when we see a patrol car,” Osorio says. She said that now she understands how African-Americans feel when police stop them. “Madre de Dios, this is how we are feeling today, being attacked for the color of our skin.”

Osorio believes the SB 4 law will empower police officers to make traffic stops based on racial profiling, even though the Texas law prohibits this. She is not alone. “We hadn’t felt that before. We did support the movements of people of color but now we are living it ourselves,” Osorio says. In case of deportation, she and her husband have already signed a power of attorney so their only daughter, who is eighteen, can legally take care of her three younger brothers and manage the family’s properties.

For Osorio, Domésticas Unidas has taught her about workers’ rights and helped her fight for them. From earning $200 per week as a minor for taking care of a child six days a week to bringing her knowledge about worker’s rights to her interactions with her own domestic employees, Osorio has come a long way. “I was not aware I was being taken advantage off until [Domésticas Unidas] opened my eyes,” she says.

For women like Osorio, Domésticas Unidas is a tool to advocate for herself, and a way to create change for other domestic workers. During the next months, the domésticas will continue fighting SB 4 and other laws that they consider anti-immigrant or racist while defending their rights as domestic workers in their spare time. Like when they won their bus route back, these señoras are working hard until their next victory, whenever that may be.