Sarah Wilson visited Big Bend National Park for the first time in the 1990s, when she was fourteen. There, on a school field trip, she and her classmates pitched tents at the Cottonwood Campground—a quiet, shady oasis tucked away in the park’s western corner—and stayed up late to stargaze. “I remember walking down towards the Rio Grande with some friends one night, laying down near the banks, and looking up at the sky,” Wilson says. “I had never seen stars like that. I was in awe.”

Inspired by the photography of longtime Marathon resident and Big Bend denizen James Evans, Wilson returned a few years later during a summer break from college, at NYU. The following year she returned yet again, this time to work as an assistant for Evans. The setting couldn’t have been more different from that of New York City. “The open skies and the quiet were a needed break from the high energy. Being in the company of jackrabbits and snakes and ocotillos was good for my soul,” says Wilson, who, like Evans, appears on Texas Monthly’s masthead as a contributing photographer. “The landscape felt timeless and lawless. . . . Being there unlocked a vibrant, adventurous part of me,” a part that seems to be an inherited family trait.

Wilson’s grandfather, John A. “Jack” Wilson, a geologist and paleontologist who had a long and distinguished career at the University of Texas at Austin before his death in 2008—he is credited with founding the school’s Vertebrate Paleontology Laboratory in 1949—was devoted to the landscapes of West Texas, and Big Bend National Park in particular. Sarah Wilson’s new book, DIG: Notes on Field and Family, out now from Yoffy Press, is the exquisitely captured culmination of the many years she has spent traveling to the Big Bend region. On those trips, with cameras in tow, she hunted the dessert for fossils on paleontological digs, while at the same time searching that vast, desolate expanse for a sense of self.

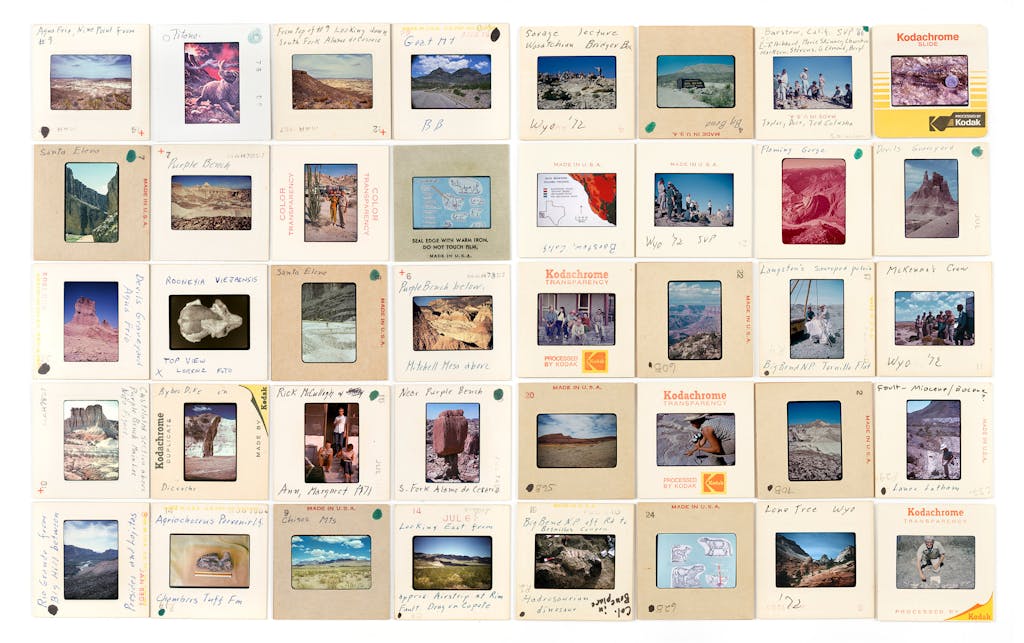

DIG draws on both Jack Wilson’s decades-long research as well as Sarah’s own experiences and observations. The result is a visually striking memoir that combines archival photography, her grandfather’s Kodachrome teaching slides, creatively staged paleontological artifacts and fossil specimens, as well as imaginative photo illustrations.

The project has been in the works for a decade. Starting in 2013, Sarah Wilson joined Chris Kirk, a biological anthropologist at UT-Austin, on his research trips to the region. The UT team used Wilson’s grandfather’s field notes as a resource while digging at some of the same sites he studied, among which is the spot where Jack Wilson discovered a near perfectly intact skull belonging to a 38-million-year-old primate, Rooneyia viejaensis, the only known specimen to have ever been found. No more have yet turned up, but other exciting finds have.

“On one of my first digs with Chris and the UT field crew we set out into the landscape at one of the fossil localities,” Wilson says. “Within about seven minutes of searching, I found a jawbone with several perfect teeth in it, sitting right there on the surface of the bentonite. I didn’t know what animal these teeth came from, so I showed it to Chris and he got very excited. It was from an animal called Texadon, a deer-like creature that lived 43 million years ago.”

In DIG, Wilson recalls retracing the same West Texas landscape her grandfather studied, photographing the same features and even scattering his ashes over the desert. She now holds the title of artist in residence at the Vertebrate Paleontology Collections that he founded more than seventy years ago. “I wish I could have had the chance to join him in the field,” she says. “For now, I am content with becoming a master fossil finder and an interested gleaner of information from the experts around me. I am grateful for this new part of my life. I love being entrenched in the landscape under sunny skies, fully present and focused, discovering 40-million-year-old bones. It really offers some perspective on things.”

Soon Texans will have more chances to see Wilson’s work in person. In Austin, Claire Oswalt’s studio at the Charles Moore Foundation will host a preview of her upcoming art show by appointment from April 27–May 3. And then from June 1–30, the larger show, which will showcase Wilson’s images of West Texas landscapes, fossils collected by her grandfather, as well as original art, will be up in Marfa at the Do Right Hall. Wilson partnered with Refractory, a Chicago design studio, foundry, and glassworks atelier, to create a cast glass sculpture of a saber-toothed cat skull, and the multimedia show will include fossil casts on loan from UT’s Paleontology Collections. Wilson will also discuss her book at the Marfa Agave Festival, which runs June 1–4.

In the meantime, Wilson continues to work on documentary films with her husband, director Keith Maitland, as well as her commercial photography. “But there’s so much to discover and create at the confluence of science and art,” she says, “and I know there’s more of that in my future.”

Wilson is also passing on the family passion to the next generation. She’s taken her seven-year-old son, Theo, to Shoal Creek in Austin, where he likes to spot ancient oyster shells and glittery pyrite. He’s proud of his collection at home in Austin, which, she says, he keeps in meticulous order. “If you were to ask him what he wants to be when he grows up, he will not hesitate to tell you that he’s going to be a paleontologist.”