First came the sound of someone running hard on the breezeway outside, then a banging on the apartment door. Irene Vera opened it to see her neighbor, twenty-year-old Rosa Jimenez, holding a little boy who lay limp in her arms. “Help me! Help me!” Jimenez cried hysterically in Spanish. The boy, she said, had choked on something he had swallowed. Bryan Gutierrez was only 21 months old, and Vera took him and lay him on the floor, then stuck her finger in his mouth, trying to find whatever might be there. Bryan kept biting down, though, so she stopped. When another neighbor showed up, Vera yelled at her to call 911. Jimenez, Bryan’s babysitter, stood to the side, sobbing. “M’ijo,” she said through tears, “what’s wrong? What’s wrong?”

It was 1:30 in the afternoon on January 30, 2003, and the police arrived shortly thereafter at the Sam Rayburn Apartments in a run-down North Austin neighborhood. An officer tried CPR on Bryan, who had no pulse. Paramedics showed up and tried to resuscitate him, injecting drugs to get his heart working again. A fireman placed a bag valve mask over the boy’s mouth and fruitlessly tried to pump air in. Something was blocking the airway. Finally, one of the paramedics reached deep inside Bryan’s throat with forceps and pulled out a large bloody mass of paper towels that was, as another paramedic later described it, the size of a large egg. Bryan was rushed to Children’s Hospital of Austin and put on a ventilator, but by then the lack of oxygen had rendered him brain-dead.

The size of the wad of paper towels became a prime topic of conversation among the paramedics, ER doctors, and police officers. There was no way, many of them agreed, that a toddler could have forced something that large that far down his own throat. Meanwhile, back at Jimenez’s apartment, police officers found a roll of paper towels on the couch and some traces of blood in the bathroom. The police needed to know exactly what happened to Bryan, so by midafternoon one of them asked Jimenez if she would go to the station to answer some questions.

Once there, Jimenez, who was five feet two inches tall with a girlish face and long black hair, sat down with a bilingual officer, Eric de los Santos, and gave him some of her background. She came to the United States for the same reason many Mexicans do: to earn money to send back home. Jimenez had been born in 1982, in Ecatepec, a large suburb of Mexico City, and grew up poor, the middle child of five. She never knew her father, and her mother sold tamales from a small pushcart. When Jimenez was seventeen, she dropped out of school and headed north, illegally crossing the Rio Grande and making her way to Austin, where she knew a couple of people. She didn’t speak English and struggled to find work and even considered returning home—until she met a young man named Fidel Juarez, who was her roommate’s husband’s cousin. The two began dating, and by early 2003 they had a year-old daughter, Brenda, and a son on the way.

Jimenez, seven months pregnant, told Officer de los Santos that Juarez worked for a roofing company while she stayed home and took care of Brenda. For the previous seven months, two or three days a week, she had also been caring for Bryan, whose mother was in the country illegally, too, and paid Jimenez $12 for five or six hours.

After Bryan was dropped off that morning at nine, Jimenez told de los Santos, the boy and Brenda napped, then they got up and played and watched cartoons. Both kids had colds, and at one point Jimenez grabbed a roll of paper towels, tore one off, and wiped their noses with it. Soon Bryan and Brenda were ripping off pieces of the towels—white with blue and pink butterflies—and throwing them. Jimenez told them to stop. Then, while the kids played and watched TV, she cooked lunch. Soon after that, Jimenez said, she saw Bryan walking slowly toward her, his hand at his throat. Jimenez realized he was choking, so she grabbed him and ran to the bathroom, where she slapped him on the back and tried to open his mouth. He bit down. Panicking, she picked him up and ran to her neighbor Vera for help. “I love him as if he were my son,” she told de los Santos.

The officer pressed her for more information about how Bryan had gotten the paper lodged in his throat. Like the emergency responders, he figured a small child couldn’t have done it by himself. Jimenez said she didn’t know how he did it. Soon de los Santos was suggesting otherwise. “You wanted some moments of peace,” he said, “and you put the towel inside his mouth.”

“No,” she replied.

The officer offered a theory: she had done this because she was angry with Bryan. She insisted she was not. He pushed the idea again—and then again. More than twenty times, de los Santos either asked if she had been angry or declared that she was. No, she responded.

“Not even a little?”

“I’m sure. I did not get angry.”

“With everything that’s happening? You want to cook, want to clean, the children are fighting . . .”

“Well, I do that every day.”

The interview grew more and more intense, but Jimenez didn’t waver. “I haven’t done anything bad,” she insisted. Finally, after more than five hours of questioning, de los Santos took Jimenez home. At around 11 p.m., she was arrested. The charge: injury to a child, a first-degree felony punishable by as many as 99 years in prison. There was no physical evidence directly tying her to a crime. Bryan showed no signs of any other trauma that would indicate an assault (such as bruises or cuts on his mouth, lips, and cheeks). And Jimenez had no criminal record or history of physical abuse or substance abuse. Yet when Bryan died three months later, Jimenez was also indicted for murder. By the time of her 2005 trial, she had become one of the most notorious defendants in modern Austin history, the babysitter accused of an almost unspeakable act of violence. When Jimenez was convicted and sentenced to 99 years, prosecutor Allison Wetzel spoke of justice delivered: “This is the kind of sentence that’s appropriate when someone murders a child.”

But had Rosa Jimenez murdered a child? Had she even committed a crime? Jimenez had always claimed she was innocent, and in the years after her conviction, as her case wound through the appellate courts, she began to gain champions who believed her, from pro bono lawyers and a documentary filmmaker to the president of Mexico.

Most notable were four American judges who either pronounced that her first trial had been constitutionally unfair or expressed grave doubts about the verdict. Unfortunately for Jimenez, each time she was awarded a new trial, the state of Texas argued that she didn’t deserve one. For a decade the conflict raged, and it finally appeared to be coming to a head this year. Federal district judge Lee Yeakel gave the Texas attorney general’s office a deadline of February 25, 2020: either set Jimenez free, Yeakel wrote, or retry her.

On the morning of January 14, 2020, almost seventeen years after little Bryan was rushed to the hospital, U.S. magistrate judge Andrew Austin held a hearing on the Jimenez case. The attorney general’s office, which handles appeals when state criminal cases move into the federal courts, wanted to cancel the deadline and allow the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals time to pass judgment on whether Jimenez deserved a new trial—which could take another year or two to decide.

“We are fearful that this life sentence is going to turn into a death sentence for her.”

Judge Austin—who had already ruled on the Jimenez case once, writing that “justice and fundamental fairness” required that she get a new trial—grew increasingly frustrated as he listened to the arguments. For twenty minutes, the judge, wearing a long black robe and a stern countenance, grilled the attorney general’s lawyers as well as a team from the Travis County district attorney’s office, which had originally prosecuted the case. And then he snapped. “Sit down,” Austin barked at a member of the AG’s staff, who had been addressing him. “Sit down. I mean, come on. Really?” He sighed loudly.

Federal judges rarely express their feelings about the innocence of a petitioner before the court. But as the hearing neared its end, Judge Austin, who had been on the federal bench for twenty years, grew more and more plainspoken about his feelings on Jimenez’s position. He cited the opinions of three other judges who’d questioned the original trial’s fairness. All four, including himself, he said, “think this is a very infirm trial and that there is likely an innocent woman who is sitting in a jail for seventeen years.” Austin was especially concerned because of what he called Jimenez’s “medical issues.” She had recently been diagnosed with stage-four chronic kidney disease. Making her spend another year or more in prison while the higher court deliberated would lead, Austin said, to “irreparable” harm. In the words of one of Jimenez’s lawyers, Vanessa Potkin, “We are fearful that this life sentence is going to turn into a death sentence for her.”

“This is not a normal case,” Austin concluded. “It’s distressing to me that we’re just treating this like it’s just an average case and we’re just going to kind of go through the motions.”

The State of Texas v. Rosa Estela Olvera Jimenez is definitely not a normal case—and it would get even stranger in the months after the hearing, when District Attorney Margaret Moore would eventually cross over to Jimenez’s side and contend that the inmate did not get a fair trial. If you believe Moore, Judge Austin, and the other dissenting judges (a fifth one recently joined them), this is one of those rare cases that shows how the processes the criminal justice system relies on don’t always deliver justice, even when everyone does things mostly by the book. It’s not that anyone involved in Jimenez’s case acted in bad faith, as is common in wrongful convictions. No law enforcement officers botched the investigation. No prosecutors hid evidence. No witnesses lied on the stand. Everyone worked within the rules, though some did so more effectively than others. Over the years, both sides have made legitimate arguments about why Jimenez’s trial was or was not fair. But today, even as the DA herself argues that the trial was flawed, the state attorney general’s office continues to fight to preserve a guilty verdict against a defendant who is almost certainly innocent, who has spent nearly half her life behind bars, and who may soon end her days there.

Like any proceeding involving a dead child—especially one the state claimed had been brutally murdered—the trial of Rosa Jimenez was an intense, heated affair. The prosecution was led by Allison Wetzel, a fierce children’s advocate and veteran of the district attorney’s child abuse division. Jimenez’s court-appointed lawyer, Leonard Martinez, was known as a passionate defender. During the weeklong trial, emotional testimony filled the courtroom of Judge Jon Wisser. Bryan’s mother cried as she talked about the death of her only child, an active little boy with big eyes and a wide smile. Jimenez wept as everyone listened to the 911 recording. Hardened police officers and veteran doctors blinked away tears as they testified and listened to details of the boy’s struggle. At one point, Bryan’s uncle, the closest thing the baby had to a father figure, started hyperventilating and had to be carried from the courthouse on a stretcher.

The prosecution’s case against Jimenez was simple: because a 21-month-old child couldn’t have put a wad of five paper towels down his throat, someone else must have done it—and Jimenez was the only adult in the room. The state brought in four expert witnesses to make its case. One was the ER doctor, who said the nearly fist-size wad was “way beyond what I’ve ever seen any other kid ingest.” The boy’s gag reflex would push it out, he said, an opinion shared by the pediatric ICU doctor, who said, “There is no way that Bryan put this in his mouth all by himself.” Bryan would have had to have been forcibly held down, she testified. A forensic pathologist said the throat of a child that age was too narrow to take in something like this voluntarily, adding that “the physics of it are impossible.” A pediatrics and child-abuse specialist said about the possibility of Bryan’s having done it to himself: “I don’t see how all that can happen.”

The state also focused on what it portrayed as suspicious things Jimenez had said during the investigation. She had made inconsistent statements about how she had found Bryan (first she said he was walking toward her, next that he was on the floor). And then, during the interrogation, she had asked de los Santos if they could talk outside. Sure, he said. This happened just after she had learned that Child Protective Services had taken her daughter, Brenda, from her husband. Once outside, she asked de los Santos, “If I were to tell you that I did it, what would happen?” He wasn’t sure, he answered, but she’d possibly go to prison. He pressed her again to tell what happened and she replied, “I first want to see my daughter.” De los Santos arranged for Brenda to be brought to the police station, where she was held by a caseworker and Jimenez was allowed to talk to her. After a few minutes Brenda was taken away. De los Santos asked her again to tell him why Bryan had choked. “I can’t,” she said. The prosecution thought this was highly suspicious, the sign of a manipulative criminal.

Martinez, aided by attorneys Catherine Haenni and Jon Evans, countered with a simple case as well: there was no physical proof (such as DNA) that Jimenez had stuffed the paper towels in Bryan’s mouth. Martinez argued that the various efforts to get the wad out of Bryan’s mouth and to resuscitate him may have pushed it deeper into his throat. The police officer who tried CPR had never performed it before. As for Jimenez’s inconsistent statements, Martinez said, they were the result of her panic. Her question to de los Santos about what could happen to her was a sign of her desperation to see her daughter. (Her first question to the officer when they got outside was, “Why did they take the little girl from my husband?”) Several character witnesses, including a mother whose kids Jimenez had babysat, used words like “peaceful” and “loving” to describe Jimenez. No one had ever even seen her get angry.

To counter the state’s experts, Martinez brought in a Connecticut medical examiner named Ira Kanfer. Martinez had tried to get others—especially experts who had pediatric training or who knew something about choking—but they refused: one because he felt the expert-witness fee Martinez offered wasn’t sufficient and another because she said she was still owed payment from a previous case in Travis County.

Kanfer had no pediatric training and little clinical experience, and he wasn’t a member of any relevant professional organizations, such as the American Academy of Forensic Scientists. On the stand he leafed through a series of articles he had printed from the internet on children and choking.

He testified that this tragedy was an accident—the lack of trauma on the boy’s face proved that. “I mean,” he said, “you get a two-year-old kid, you try to stuff this thing down their throat, this kid’s going to be fighting like hell.” He testified that a toddler was absolutely capable of wadding up paper towels and swallowing them; maybe he’d dropped them in the commode (the boy liked to throw things there, including, at least once, a roll of toilet paper), making them easy to compress. Kanfer held up an empty toilet paper tube and told of an experiment he had done when he wadded up five paper towels, soaked them, and they “dropped like a lead weight, right through this tube.”

Wetzel sharply questioned Kanfer about his credentials. She pointed out that in a nineteen-year career he had written only a handful of abstracts—short articles with titles such as “Unusual Methods of Suicide in Connecticut” and “How to Turn a Homicide Into an Accident.” During a break, an angry Kanfer saw Wetzel and assistant DA Gary Cobb in the hallway and told them they could “go f— themselves.” Back in court, Wetzel badgered Kanfer further about his expertise and wrapped up her questioning by asking about the hallway exchange; at least one juror laughed out loud. Martinez didn’t object to Wetzel’s question, which most lawyers would have done since it had nothing to do with the case. Wetzel provoked Kanfer with the statement again, and finally Martinez pushed back, though he didn’t make a motion for a mistrial, as he could have, nor did he do so when Wetzel brought it up a third time. “Leonard just sat there,” his co-counsel Haenni told me. “I kept whispering to him, ‘Object! Object!’ I thought her questioning was outrageous.” Martinez later explained his strategy of rarely objecting against Wetzel: he wanted the jury “to hate her” so he gave her “a great deal of leeway as I thought her behavior would alienate a jury.”

Wetzel made her case to the jury with the same simple logic that had been used to bring Jimenez to trial in the first place. “Use your common sense,” she implored jurors; a toddler couldn’t have done that to himself. Jurors, many of whom had wiped tears from their eyes over the previous week, agreed. When Jimenez heard her 99-year sentence, she stared straight ahead for a few moments, as if paralyzed. Finally, she buried her head in her arms and wept. A few weeks later she was sent to the Lucile Plane State Jail, in East Texas.

As Gajá filmed, she was struck by a realization: there was absolutely no physical evidence that Jimenez had killed Bryan.

Jimenez would probably have been long forgotten if not for another young Mexican woman whom she had met a year before her sentencing. Lucía Gajá was a Mexico City filmmaker who had made several short documentaries after graduating from film school in 1999. She wanted to make a film about Mexican women in U.S. prisons—how they had left home trying to make new lives for themselves but got caught up in a world they didn’t understand, sometimes tragically. In 2004 Gajá got in touch with Carmen Cortes Harms, who worked for the Mexican Consulate in Austin as a liaison between Mexican female prisoners and their families. Cortes gave Gajá a list of 21 women behind bars, 20 of whom had already been convicted. Gajá met them and then was introduced to number 21: Jimenez, who was still in the Travis County Correctional Complex awaiting trial. The filmmaker thought Jimenez’s case would be a good vehicle for analyzing the U.S. judicial process. It was February 2005, six months before Jimenez would go on trial, and Gajá got permission to film the inmate in jail and in court.

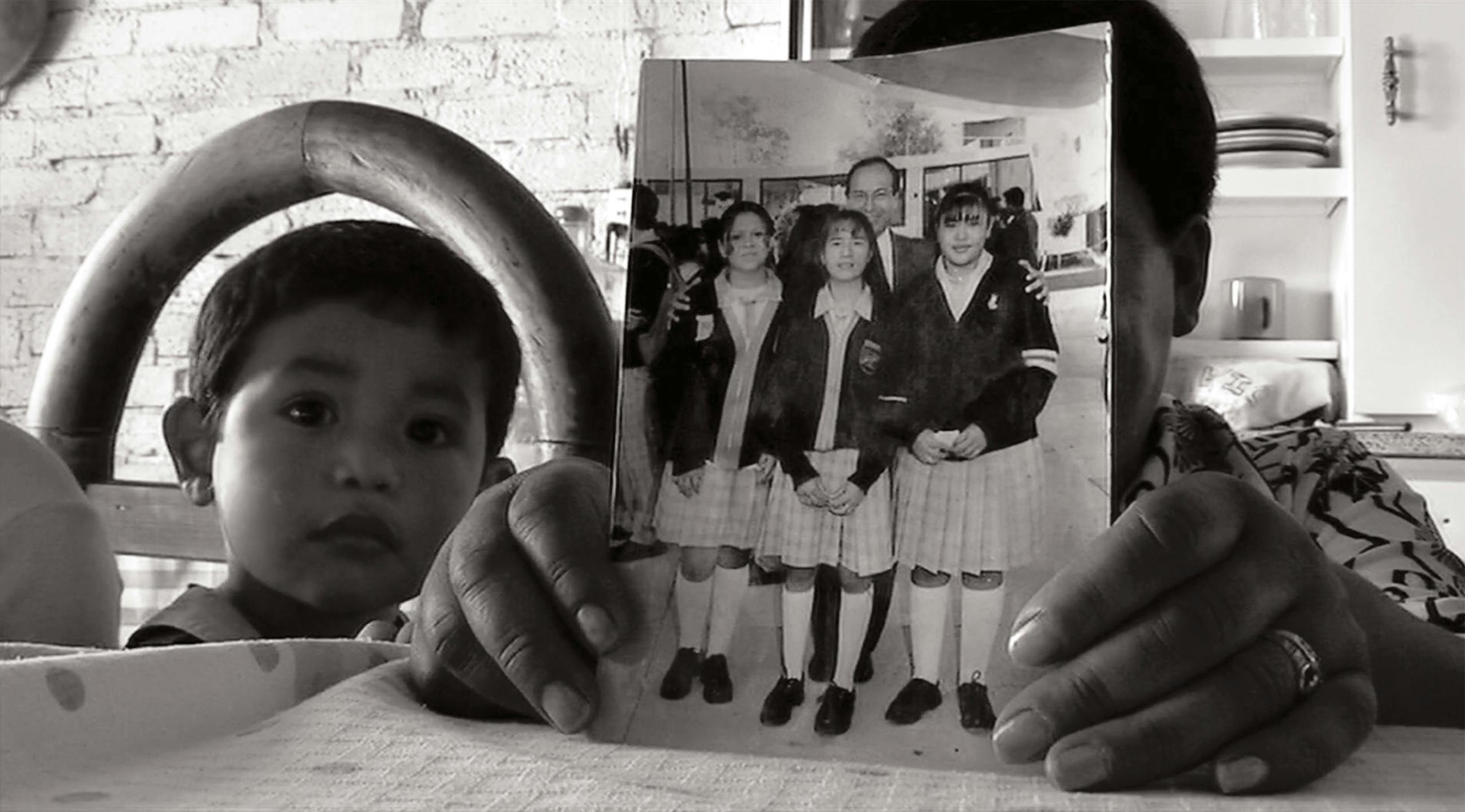

Jimenez told Gajá what she told everyone else: that she didn’t kill Bryan. Gajá didn’t know whether to believe her. Jimenez seemed like a nice person. She showed Gajá photos of her husband and children (her son, Emmanuel, had been born while she was still in jail and taken from her three days later) and cried when talking about how much she missed her mother, Estela. She cried, too, when talking about Bryan. “I don’t know how it happened,” she said in Spanish. “The boy is dead and that has affected me a lot. It was an accident.”

But then the trial began, and, as Gajá filmed, she was struck by a realization: there was absolutely no physical evidence that Jimenez had killed Bryan. Every day, a paramedic, cop, or doctor got up on the stand and insisted the babysitter had stuffed the paper towels in Bryan’s throat because the boy couldn’t have done it himself. All of that, combined with the absence of a motive, the lack of marks on the boy’s face, and the fact that Jimenez had no prior criminal or violent history, made Gajá wonder: Could Jimenez be telling the truth?

By the end of the trial, Gajá felt certain that Jimenez, who didn’t speak English and had no money to hire an expensive lawyer or pay for more (and more credible) experts, had been wrongly accused and convicted—borne along in the emotional aftermath of a helpless child’s death. Someone had to be held accountable for Bryan’s tragic death, she thought, and the obvious person was his babysitter. “They thought she was guilty from the start,” Gajá told me. “From the first day she didn’t stand a chance.”

Motivated by the sense that she had witnessed a terrible injustice, Gajá returned to Mexico City and began to put the film together, using trial footage to support her theory that well-meaning professionals had been driven by outrage, not facts. There was the young paramedic who worked on Bryan and who testified that at first the responders all thought it was an accident, until the wad was extracted. “It was shocking” how large it was, she said. “We no longer assumed the scene to be an accident.” There was the ICU doctor who had never before encountered a wad of paper towels like this in a child’s throat but was absolutely certain it had been forced there by someone else. “The fact that I’ve never seen it keeps me from sleeping at night,” she testified.

Gajá had shot footage of prosecutor Wetzel during closing arguments, her voice sometimes choked with emotion. A successful prosecutor will create a compelling narrative of a crime to make her case to a jury, sometimes relying on speculation, and that’s exactly what Wetzel did, summarizing the monstrous things that she theorized Jimenez, “this child killer,” had done: “She used a lot of force, she pried his mouth open,” Wetzel said. “She’s holding his face, she’s pushing it and pushing it down far so it will get far down there.” Wetzel was relentless with her narrative. “She held him down while he struggled. Once he was quiet, she kept pushing.” Jimenez’s motive, she conjectured: “She killed him out of anger.”

Gajá’s film flowed from one emotional scene to another, showing, in retrospect, how easy it was to convict Jimenez. Searching for a way to summarize Jimenez’s journey into the U.S. criminal justice system, the director used footage of defense attorney Haenni near the end the film. “I think that if this would have happened to somebody in West Austin, a middle-, upper-class, educated person, that person probably would not have ended up in the same situation as Rosa,” said Haenni. “I think it was very easy for them because she’s Mexican, she’s poor, she’s illegal. She didn’t know her rights. In the interview, if that would have happened to me, after the second time this guy told me I did it, I probably would have used some very ugly words and I would have asked him how many times do I need to tell you: ‘I didn’t do it, I can’t tell you anything else, and I want a lawyer now.’ Because she was being accused of having done something she didn’t do. Anybody who would have known the system better, had more money, more resources, would have been able to put up a much better fight.”

Gajá’s gritty documentary Mi Vida Dentro (My Life Inside) came out two years after the trial and caused a stir in her home country. Viewers couldn’t take their eyes off Jimenez, who spoke quietly as tears rolled down her cheeks. “The country took away from me what I most loved,” she said. “My children. My husband. My mother. My freedom. My happiness. Everything a woman yearns for, they took away from me. In one day.” Jimenez came across as warm and open, if still bewildered. She was learning English behind bars and had also discovered a talent for drawing. Her cell was decorated with her artwork as well as cards and letters from her children. The camera focused on a letter Jimenez had just written her mother. “Hola mami!” it began.

Mi Vida Dentro struck a nerve among Mexican viewers, many of whom knew first- or secondhand how the dream of crossing the border could turn into a nightmare. They wrote outraged letters to the governor of the state of Mexico (which surrounds Mexico City on three sides) as well as the country’s president, asking them to do something. A legal defense fund was set up, and activists began hosting fundraisers; at one of them, Jimenez’s mother sold tamales. The film was nominated for several awards and won best documentary at the Morelia International Film Festival. It had its U.S. premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival.

The Mexican government hired a lawyer, Yuriria Marvan, to find a U.S. lawyer who could help Jimenez. “The documentary became a symbol of people that go to the U.S., work hard, find themselves in unfair situations, and end up being discriminated against,” Marvan told me. “Rosa is a mother, a woman, and this happened while taking care of another baby. The maternal culture in Mexico is very strong.” Marvan brought in Bryce Benjet, an Austin civil lawyer who also worked on death penalty cases. (At the time, he was representing death row inmate Rodney Reed, who also claimed innocence and whose case would eventually become internationally known.)

Benjet began calling well-known children’s hospitals, looking for pediatric otolaryngology (ear, nose, and throat) experts who knew something about choking. At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, one of the most renowned in the country, he reached Karen Zur, a surgeon and professor who was also the associate director of the Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders. After looking at the evidence, Zur was adamant, she wrote in an affidavit, that “it is absolutely possible that the child in this case could have stuffed paper towels into his mouth and then accidentally choked on them.” She added that “nothing about the size of the obstruction rules out an accidental choking incident.” She also explained that the gag reflex doesn’t always push something out; sometimes it can draw an object farther in.

Zur’s opinion was affirmed by three other pediatric specialists. “It is entirely possible, and even likely, that [Bryan] accidentally placed a large wad of paper towel in his mouth that became lodged in his throat,” said an anesthesiologist and critical care doctor. Another pediatric otolaryngologist gave an affidavit in which he told of removing a similar-sized wad of bread from the throat of a 28-month-old. A pediatric forensic pathologist who had conducted numerous autopsies on kids, including suffocations, said, “There is nothing unusual or impossible for a child to place a large wad of paper towel in his mouth.” She had seen the photos of the wad. “The oropharynx of a child [Bryan’s] age can accommodate objects of this size, even without chewing.” The fact that there were no other suspicious injuries on Bryan made her think his death was an accident.

The pathologist also gave her opinion of the state’s experts: She was not impressed. “I was struck by the level of speculation,” she wrote. “None of the people who testified spoke to the actual facts of the event. Also, none of the experts in the case had the necessary training and experience, or consulted with persons with this specialized knowledge, in order to give a reliable opinion. None of the experts referred to the scientific elements supporting their conclusions or the specific physical and anatomical vulnerability of a child this age’s airway, which makes accidental choking a leading cause of death.”

Benjet felt he had the tools to free Jimenez. There was no science behind Jimenez’s conviction, and the “common sense” was nonsense, rejected by experienced specialists who all insisted that a toddler could very well have swallowed those paper towels. Jimenez had already had her first appeal denied, but in 2010 Benjet filed a writ of habeas corpus—an appeal challenging the basic fairness of the trial. The brief highlighted the opinions of the specialists he’d consulted, but the legal claims focused on the “ineffectiveness” of Jimenez’s expert and lawyer. Ira Kanfer not only lacked the necessary expertise to talk about what happened to Bryan, Benjet wrote, but he also “self-destructed” on the stand. “By the end of his testimony, Dr. Kanfer had no credibility.” The brief also blamed Judge Wisser for not releasing funds for more experts during the original trial. (Wisser had funded two other experts, a psychologist and an artist who made an illustration of a child’s airway to demonstrate Kanfer’s theory.) Benjet saved much of his scorn for Martinez—not only for failing to hire a more competent expert on choking but also because he didn’t object when the prosecution made an issue of Kanfer’s four-letter word or move for a mistrial when Kanfer fell apart on the stand.

“Judges will sometimes encounter convictions that they believe to be mistaken, but that they must nonetheless uphold.”

State district judge Charlie Baird called a December hearing, and experts from both sides testified. Afterward, he did something appellate judges rarely do: he threw out the verdict, writing that Jimenez’s trial was “fatally infected by constitutional error.” The move paved the way for a new trial. Having Kanfer as an expert, Baird wrote, was worse than having no expert at all. “In my thirty years as a licensed attorney, twenty years in the judiciary, this Court has never seen such unprofessional and biased conduct from any witness, much less from a purported expert.” Baird faulted Martinez for hiring Kanfer but also for failing to secure funding for more experts. Like Benjet, he also blamed Wisser for not providing the money. For his part, Martinez claimed in an affidavit to the court that, in an informal meeting with Wisser, he had unsuccessfully asked for more funding. However, because Martinez had made no written record of that request, it couldn’t be used later in Jimenez’s appeals. Judge Wisser denied the request had been made. Baird capped his opinion by asserting that Jimenez’s new pediatric specialists “effectively rebutted the State’s theory of guilt.”

When Jimenez heard, she was ecstatic. It’s a miracle, she prayed, thanking God. She thought that because a judge said she deserved a second chance, she would be released any day.

But that’s not how things work in the criminal justice system. Baird’s decision had to be ratified by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, the state’s highest criminal court. In just five years, Jimenez had already seen her case move dramatically through the courts, from “guilty” to “deserves a new trial.” Two years after Baird’s judgment, in 2012, the CCA overruled him and reversed Jimenez’s status back to “guilty.” Martinez had done an adequate job, the court wrote, and so had Kanfer, who had come to the same conclusion as the three newer experts. The Constitution doesn’t require an “equivalency of experts,” said the court, noting that ultimately, “the credibility of dueling experts is for a jury to decide.” Though the opinion was unanimous, Judge Cathy Cochran also quoted a recent Supreme Court decision that seemed to hint at qualms she and other judges felt when reviewing Jimenez’s case. “Because rational people can sometimes disagree,” the decision read, “judges will sometimes encounter convictions that they believe to be mistaken, but that they must nonetheless uphold.”

Jimenez was crushed by the decision, but Benjet, now working for the Innocence Project, a New York–based nonprofit that had already helped free nearly two hundred wrongly convicted inmates, assured her that the fight wasn’t over. He raised her spirits later that year when he told her that Judge Wisser had written an unusual letter to the district attorney at the time, Rosemary Lehmberg, sharing his concerns about the case. Like others, Wisser noted that Jimenez had no motive and no history of violence. While he thought the trial had been fair, he emphasized that there was an “inherent danger of wrongful conviction” in cases like this that involved dead children. “I believe now,” wrote Wisser, “as I did at the time of the trial, that there is a substantial likelihood that the defendant was not guilty.”

Armed with the words of the two judges and the three new experts, in 2012 Benjet filed a petition with the U.S. Supreme Court, asserting that Jimenez was denied a fair trial because of bad lawyering. He attached briefs from legal scholars and one from Enrique Peña Nieto, the president-elect of Mexico. “The citizens of Mexico and their government leaders have been shocked by Rosa Jimenez’s treatment in the Texas criminal-justice system,” Peña Nieto wrote. “Americans would surely be alarmed—and rightly so—if a U.S. citizen received a 99-year sentence in Mexico based on the facts in Rosa’s trial and habeas proceedings.”

The Supreme Court refused to hear the case, leaving Benjet (assisted by Dallas lawyer Sara Ann Brown) with one final option: a writ of habeas corpus in federal court, where an inmate can appeal the denial of habeas in the state court. It’s a high bar to clear; defense lawyers have to show that the state’s decision was contrary to federal law or was “based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence.” Federal courts rarely overturn state courts’ decisions in such cases.

Once again, Jimenez has to wait for a court to ponder whether to heed a judge who believed she was wrongly convicted.

For Benjet and Brown, the issue was the same as it had been in the state habeas proceeding: a poor defendant has a right to a fair trial, including in cases that necessitate expert testimony. Not only was Kanfer unqualified, they argued, but also the new experts’ testimony revealed that the state’s witnesses had shown a basic misunderstanding of how a child’s airway worked. Otolaryngologists were qualified to determine whether an accidental choking was possible; emergency-care doctors who had used no science (for example, nobody ever measured the boy’s throat) were not.

For the second time in a decade, Benjet’s arguments found a sympathetic judicial ear. This time it was magistrate judge Austin, who in 2018 wrote a report to Lee Yeakel, the federal district judge, finding that Jimenez’s attorney had been ineffective and Kanfer unqualified. “By definition, expert testimony requires ‘expertise,’ ” Austin wrote. He recommended that Yeakel throw out the verdict and grant a new trial. In October of last year Yeakel did just that, issuing the deadline—February 25, 2020—by which the state needed to release Jimenez or begin new proceedings.

The attorney general’s office, which had already written that “this case is about common sense, not forensics,” appealed the deadline. The appeals led to the January 14 hearing in Austin’s court, but the whole issue was made moot two weeks later when a three-judge panel of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals threw out Yeakel’s deadline. Now the full, sixteen-judge panel of the Fifth Circuit would be responsible for deciding whether Jimenez deserved a new trial at all.

Once again, Jimenez had to wait for a court to ponder whether to heed a judge who believed she was wrongly convicted. This time, though, the wait threatened more than her freedom. She now suffers from a chronic health issue that has her one step away from kidney failure. If the disease progresses, she will need dialysis and possibly a transplant. Unfortunately for Jimenez, who gets to see a doctor only every three months, it’s almost impossible for prison inmates to get on a transplant-eligibility list. Worse, the condition has compromised her immune system, putting her at greater risk of severe complications if she were to contract the novel coronavirus, which has been marching inexorably through the Texas prison system.

When Jimenez came to the United States as an undocumented immigrant, she knew almost no one. Now, convicted of murder, she has made numerous friends, many of whom wrote her sympathetic letters after they saw Mi Vida Dentro. It made her feel good to have strangers believe in her innocence, and she eagerly wrote them back. She’s kept it up for more than a decade, and now, housed at the Mountain View Unit in Gatesville, she spends her weekends corresponding with friends as well as drawing and painting watercolors. During the week she works as a graphic designer for a prison program that puts together braille textbooks for schools. She started doing the work two years ago. “I fell in love with it,” she told me in English. “It’s like learning a new language.”

Sitting in the prison visitors room, Jimenez looks very much like she did in Mi Vida Dentro, as if preserved under glass all these years. She has a shy but warm manner, brightening when talking about her artwork or her friends. Her English is good, though she sometimes reverts to Spanish pronunciations.

Jimenez, who isn’t eligible for parole until 2033, speaks every week with her current lawyers, Brown and Vanessa Potkin of the Innocence Project, who see in her case similarities with others in which women were later exonerated. According to the Innocence Project, most female exonerees were convicted of crimes that turned out not to have been crimes at all. Of these cases, three quarters involved children, leading to emotional trials in which the defendants were prosecuted on shaky evidence and demonized. In 2007 a case remarkably like Jimenez’s went to trial in Corpus Christi, after Hannah Overton’s four-year-old foster son died of salt poisoning and she was accused of murder. Like Jimenez, Overton had been interrogated for five hours by a skeptical policeman; investigators and prosecution experts thought the death was definitely not an accident, and the prosecutor theorized that Overton committed the murder—by forcing the boy to ingest a massive amount of spicy seasoning—because she was angry. In words similar to Wetzel’s, the prosecutor in Overton’s case painted a monstrous scenario for the jury. “Could it be that you held his nose, held his neck, and made him drink this horrible concoction?” the prosecutor asked. Though Overton denied it, the jury convicted her of murder and sent her away for life. Seven years later, after evidence surfaced that the boy almost certainly died accidentally, the appeals court threw out the conviction and Overton was released—and later cleared of charges.

Jimenez hopes for the same outcome, sooner rather than later, healthy rather than sick. More than anything, she wants to go home and see her mother and her children. “I want to be able to work,” she told me, “be productive, do things for my mom and kids.” She hasn’t spoken with her mother since 2005; Estela can’t come into the United States, and Jimenez can’t make international phone calls. Jimenez hasn’t heard from Fidel since 2010, when he stopped visiting and writing. Her children, who are both U.S. citizens, lived with her mother for two years in Ecatepec, then returned to the United States, where they grew up with a foster family in College Station.

Because of the nature of her crime, Jimenez wasn’t allowed to even touch her kids after she went to prison. On visiting days, other mothers would hug and kiss their children, but she could only talk to hers through a pane of plexiglass, while they fidgeted and grew bored. As a result, she wasn’t close to either of them. In January of this year, Jimenez’s daughter visited her for the first time in five years. Brenda had recently turned eighteen, and now that she was no longer a minor, she and her mom were allowed their first physical contact since 2003. For seventeen years, Jimenez told me, she had been dreaming of this day, but when the crowd came into the visitors room, she couldn’t pick Brenda out. Jimenez walked through the room, her eyes nervously darting from face to face. She was looking for the thirteen-year-old girl she had last seen through the glass.

Finally, she made eye contact with a young woman who looked a lot like her, only taller—and knew immediately she’d found her daughter. The two fell into each other’s arms. “Nothing prepared me for that,” said Jimenez. “I could finally touch her. I can’t even describe how I felt.” They sat around talking like two long-lost friends, Brenda and Rosa. Brenda told her mother that she always thought of her as a rose. Then she showed her two rose tattoos, one near her heart.

Over the past year, one of Jimenez’s most frequent visitors has been Gajá, now 45, who is hard at work finishing up a sequel to Mi Vida Dentro. After that film came out, Gajá made another movie, but she told me she couldn’t get Jimenez out of her head. So in 2018 she started filming again. “I wanted to show who she is and how you spend seventeen years of your life in a place you can’t get out of,” Gajá said. “Injustice affects people’s lives. It breaks families. It prevents a mother and her children from having the experience of being a mother and her children.” Gajá hopes the new film will be released early next year.

Before Gajá started filming again, a friend had warned her that prison changes people, makes them hard—especially inmates holding a grudge. But Gajá found Jimenez to be the same person she’d been back in 2004. “Her kindness, her smile, her tears of pain at not having a chance to be with her family. I’ve been impressed with how she has handled this. She’s very strong. She’s found a way to not be sad all the time. I mean, of course she’s sad, but you see her, and she lights up. She’s a beautiful spirit. She has a lot of love inside her.”

The death of Bryan Gutierrez still haunts his family, especially his mother, Victoria. There’s not a day that goes by that she doesn’t think of her son, the happy baby who would cry for her when she left the apartment for work. She told me she talks about Bryan all the time with her three daughters, whose ages range from two to eleven. They visit his grave often, where his tombstone reads “Little Angel.” Victoria believes, as she did seventeen years ago, that Jimenez is guilty. “For a little boy to do that, it’s not possible,” she said. “It wasn’t just one paper towel, or two, or three, or four. It was five paper towels.”

Rosa Jimenez’s trial still haunts other people too—especially the judges who haven’t been able to do anything about what they regard as an unjust jury verdict. And now this group has a surprising fifth member. In February I reached out to Cathy Cochran, who wrote the 2012 Texas Court of Criminal Appeals opinion reversing the decision to grant Jimenez a new trial. “I remember that case all too well,” Cochran told me, “as an instance in which the law just didn’t provide the right answers to a truly tragic situation.” Cochran, who retired in 2014, said that though she had been sympathetic to Jimenez’s appeal, she found herself unable to do anything about it. “Sometimes you have an intuition that things just aren’t right, but you can’t find a legal way to save that one apple without upsetting the whole applecart.”

The issue, according to the widely respected jurist and law professor, is this: “Our system promises a fundamentally fair trial that should lead to an accurate result, and normally the system gets it right. Sometimes, the trial is legally unfair, but we’re confident that the result is accurate (the courts call this ‘harmless error’), and sometimes the trial is legally unfair and we’re not so certain that the result was accurate—so courts order a new trial. The most difficult cases are like this one, where the trial seems to have been legally fair but the result seems inaccurate or just wrong, as Judge Wisser believed. Courts are not good at addressing these ‘hard’ cases, because courts deal with broad legal doctrines that have to be applied to all future cases.”

Put simply, the law promises poor defendants a lawyer and (in certain cases) an expert, but the law doesn’t promise the best lawyers and the best experts. And sometimes that results in an inadequate defense. The law also says juries get to make the final determinations on guilt or innocence. And juries are made up of humans, who sometimes make mistakes—especially in emotional matters.

Judge Wisser, who presided over the initial trial, still believes Jimenez is almost certainly innocent—“though even if she did it,” he told me, “she’s been punished adequately.” Both he and Cochran believe Jimenez got a fair trial, though. Judge Charlie Baird, who ordered a new trial back in 2010, vehemently disagrees—and bristles at the idea that appellate courts shouldn’t second-guess a jury’s verdict. “It wasn’t a fair fight. I’m convinced she’s innocent, and I’m certain that she didn’t receive a fair trial.”

Baird has an unlikely ally—or at least a partial one—in Heather Powell, the foreperson of Jimenez’s jury. “It was a really hard case for me, and for all of us,” Powell told me. “We were torn.” She says that ultimately the jury voted with common sense. “It came down to: there’s no way a twenty-one-month-old could have shoved that big a wad of paper towels that far down his throat.” Though she still believes in the verdict, she shares Baird’s certainty that Jimenez didn’t get a fair trial. “She was underdefended and underfunded, for sure. No way she got the best of what she was supposed to get.” Powell thought Martinez wasn’t very professional. “Kanfer was a complete train wreck. I was like, ‘Come on, is this the best you have?’ He was so painfully egotistical. I don’t know if a better expert would have changed my verdict, but if she had had one, she might have gotten a lesser sentence. If she’d had a better defense, she would probably not be in prison today.”

The defense team has had fifteen years to second-guess itself. Leonard Martinez admits he made some mistakes representing Jimenez but is still certain of her innocence. “This was a failure of forensics,” he said in an email. “I should have made my request for more funds for another expert I had wanted by way of an ex parte motion with denied order [a motion in writing that would also have been denied in writing]. However, I did not.”

Kanfer, now retired, still regrets his hallway outburst—and how it affected the trial. “Once I said the four-letter word, everything else was irrelevant.” Kanfer is also still deeply troubled by the trial. “I had more than four hundred court appearances, and her case is one of the saddest, most distressing cases I ever had. An innocent woman was convicted of murder.”

Judge Austin has strongly encouraged the offices of the attorney general and district attorney to work with Jimenez’s lawyers to come up with a solution. At his hearing this January, he brought up the possibility that Jimenez could plead guilty to injury to a child in exchange for time served—as a way to avoid waiting for the Fifth Circuit to rule on whether she should get a new trial and then potentially slogging through that new trial.

Judge Cochran offered a simpler solution: set Jimenez free, at least for now. “If the State can’t agree to a plea for time served,” she told me, “I think that the fairest solution would be to release Ms. Jimenez, who has significant health problems, under appropriate supervision pending the final decision of the Fifth Circuit on whether or not to retry her.” In this scenario Jimenez would be returned to the Travis County jail, at which point she could be released on bond to get medical care.

Until very recently, District Attorney Moore has been unwilling to compromise. “My analysis of this case is that the appeals for Jimenez have centered on opinion testimony,” she told me three days after the hearing in Judge Austin’s court. “There are no new facts. There are new expert opinions. They’re saying, ‘We have new experts who are more persuasive than the experts who testified at trial.’ To me, testimony like that is properly weighed by a jury.”

The district attorney is the most powerful authority in the criminal justice system, with wide discretion on whom to prosecute and with whom to make plea deals. On February 3, five state representatives sent Moore a letter, siding with Judge Austin and asking her to “take any necessary steps to ensure that justice and basic humanity carry the day.” Moore wrote back immediately, saying that she had appointed a team of lawyers to look into the feasibility of retrying Jimenez at this point, and that she had asked her office’s Conviction Integrity Unit to weigh in. If that team believed there was a wrongful conviction, Moore could go to the attorney general’s office and see about bringing the case back to state court. “There are no easy answers here,” Moore told me back in January. “It’s got to be examined from all aspects; then we have to figure out what to do.”

When Potkin and Brown read Moore’s letter, they reached out to yet another set of pediatric specialists and otolaryngologists, who reviewed the trial testimony of the prosecution’s experts and unanimously declared it unsound. By then it was March, and the coronavirus pandemic had hit Texas—and the state’s prison system. The defense attorneys presented Moore with a report from the experts as well as a letter from a kidney specialist stating that people with stage 4 kidney disease are 60 percent more susceptible than others to viral diseases like COVID-19. The lawyers had good reason to worry; by mid-April, more than six hundred inmates and staff were infected, so they filed an emergency motion with Judge Yeakel to get Jimenez out of prison while her appeal was pending. “Ms. Jimenez cannot afford to wait any longer,” Potkin wrote. “The danger is imminent.” Yeakel responded that same day, granting the motion but giving Attorney General Ken Paxton’s office a week to respond.

In the meantime, Moore’s Conviction Integrity Unit had finished its work and determined, based on the new report, that indeed Jimenez hadn’t received a fair trial. Moore then issued a stunning reversal, passing her staff’s recommendation for a new trial to Paxton’s office. “The matter is now in their hands,” she wrote to Jimenez’s attorneys on April 27. But when the AG filed a brief responding to Yeakel’s order, it said nothing about Moore’s recommendation. Instead, the brief contested Yeakel’s jurisdiction and downplayed the concerns about Jimenez catching COVID-19 as mere speculation. In a case that was already not normal, it was downright bizarre that the office of the AG was upholding a verdict that the prosecutor herself had said wasn’t fair. Yeakel called it “a great waste of everybody’s time.” (Paxton’s office declined to comment.) The Jimenez case officially went back before the Fifth Circuit, where it could very well sit for the next year while the judges consider what to do with Rosa Jimenez.

At Mountain View, Jimenez wears a mask and practices social distancing as much as she can, though it’s impossible in the dorm. “We share sinks,” she says. “There are five for everyone in the dorm, and four showers, and we all use the same water fountain.” Though she says that the prison is doing a fine job wiping down tables and benches, there are no hand sanitizers. Inmates and guards worry that Mountain View regularly endangers everyone in the facility by continuing to bring prisoners from around the state to its crisis management wing for counseling. Inmates arrive almost every day from the outside world.

Jimenez stays on top of the news, both good and bad. She knows five state representatives have joined the five judges and the many others on her side. She knows that Moore has essentially crossed over to her side, and she knows the power of the district attorney to make or break a case. But Jimenez cried when she learned that Attorney General Paxton was pushing against another attempt to set her free. “They are treating me like a ball that they are throwing at each other,” she told Potkin.

She prays a lot, and imagines home. Lately, while eating in the cafeteria or walking back to the dorm, she’s found herself having a recurring daydream in which she gets off a plane in Mexico to a large crowd of people. They are mostly in their twenties and thirties, and they are all waiting for her. As she walks through the crowd, she spies her mother, who is crying. Soon the two hug, and then Jimenez cries, too, as the crowd falls away. Then she wakes from her reverie and she’s once again sitting on her prison bed.