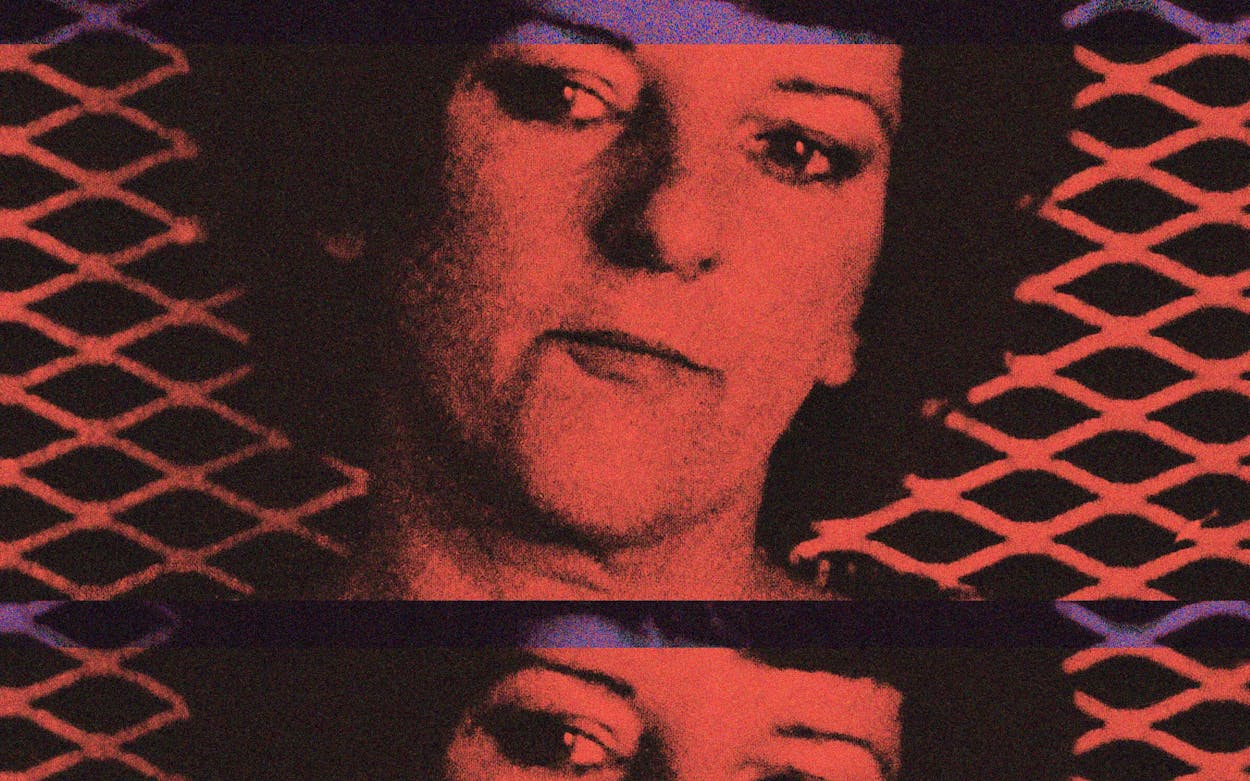

The tale of Texas baby-killer Genene Jones—the children she harmed, the people who allowed it to happen, and the long fight for justice—bookends a vast swath of my life and career. I began reporting this medical horror story nearly four decades ago, at age 24, on a freelance assignment for Texas Monthly. It led me across the Lone Star State for four months, deep into a saga that would generate international headlines, a made-for-TV movie, my first magazine article (10,000 words), and a job offer that rescued me from law school.

Certain there was a larger tale—How had she gotten away with so much, for so long? What had driven her to it?—I continued reporting. The first edition of this book was published in 1989. By then, Genene Jones, licensed vocational nurse, was regularly described as “one of America’s most prolific serial killers.” She was credibly suspected in more than a dozen unexpected baby deaths and routinely blamed for “up to sixty.” An expert at the Centers for Disease Control later found that, during a fifteen-month “epidemic period” on the 3–11 p.m. shift at the charity hospital where Jones worked in the pediatric intensive care unit, children were 25 times as likely to suffer cardiac arrest—and ten times as likely to die.

Yet, to that point, she had been convicted (in 1984) of murdering just one child, in a small-town clinic in the Texas Hill Country, where Jones had gone to work after the San Antonio hospital had quietly sent her off with a good recommendation. Family members of her many other presumed victims, whom Jones had treated in the ICU, found this maddening. But a 99-year prison sentence, imposed on Jones at age 34, seemed to ensure that she would live out her days behind bars.

Decades later, that certainty began to wane. Texas has a reputation for throw-away-the-key justice. But in 1977, the state’s legislature had passed a mandatory-release law aimed at curbing severe prison overcrowding and reducing billions in construction costs for new lockups. The impact of this measure belatedly became clear: if Jones continued accumulating outsized credits for “good time,” Texas would have no choice but to turn her loose in the spring of 2018—after she’d served just one third of her sentence for murdering fifteen-month-old Chelsea Ann McClellan.

Petti McClellan, the little girl’s mother, was onto this before anyone. McClellan had appeared regularly before the Texas parole board, helping ensure that Jones wasn’t sprung even sooner. By 2012, she’d learned there was only one way to keep Jones behind bars: prosecutors would have to prove a new murder case against her, from the events that took place in the San Antonio hospital’s ICU.

Proving homicide in a setting where children were already gravely ill had been too daunting a task for prosecutors back in the early 1980s. As the surgeon who presided over an internal investigation told me in 1983, excusing the hospital’s failure to alert criminal authorities: “If they’re sick enough to be in the pediatric ICU, they’re f—ing sick enough to die.” Key witnesses had since passed away; memories had faded; documents had been shredded—or disappeared. These infant deaths were now the coldest of cold cases. By any measure, it seemed impossible.

Thus began the improbable second life of this byzantine tragedy.

Just as she’d told me when she and I first spoke in her trailer home in San Angelo in 1983 (“I haven’t killed a damn soul!”), Genene Jones repeatedly denied to her state captors that she’d ever harmed children under her care. On August 6, 1984, in her prison-intake interview after being sentenced to ninety-nine years for murdering Chelsea McClellan, Jones flatly declared: “I’m here for something I didn’t do.”

Five years later, when Jones came up for her first discretionary parole review, she stuck to that story, according to prison records. If the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles required her to admit guilt before considering her release, Jones proclaimed, “she would never do so as she is not guilty of these offenses.” She said her criminal convictions resulted “from her efforts to assert the rights of good care for indigent children at a Bexar County Hospital facility.” If freed, she told her parole examiner, she would flee Texas “for my own safety,” explaining, “With all of the bad publicity, someone would probably kill me.”

But no one was eager to turn her loose. Jones would be denied parole in 1989, then every three years through 2014—nine times in all. For years, Jones continued to insist she’d been wronged.

Yet Jones, in exchanges thirteen years apart, also privately acknowledged varying measures of guilt. The first came in October 1998, after Jones had been incarcerated about fifteen years, during a routine thirty-minute interview with a state parole officer named Marcy Ferguson. Ferguson provided a detailed account of this conversation to prosecutors at her home two decades later, after she’d retired. She told them she would “never forget the exchange for the rest of her life.”

During her parole interview, Ferguson recalled, Jones admitted committing the two crimes of which she’d been convicted: murdering Chelsea McClellan and harming Rolando Santos. Then, as Jones was leaving the room, she stopped at the door, spun around, and sat back down. She had something she wanted to “get on the record.” That’s when Jones told her: “I really did kill those babies.” Ferguson said she began to rummage through her files on Jones’s two convictions when the inmate interrupted her to say: “You won’t find them in there.” This was even more chilling: Jones was confessing to killing children for whose deaths she’d never been charged. According to Ferguson, Jones then told her she “didn’t want to see this in Texas Monthly.”

At the time of the confession, Ferguson merely noted it in a brief comment in Jones’s confidential parole records: “Contrary to prior reports and file material, Inmate Jones admits she committed the present offenses. She tearfully stated she was sick and claims she feels bad for the victims’s families.”

In 2011, Jones also wrote the Texas nursing board, which was belatedly acting to revoke her nursing license, to apologize “for the damage I did to all because of my crime . . . I look back now on what I did and agree with you that it was heinous, that I was heinous.” The board revoked Jones’s license to practice nursing on June 10, 2011. Her letter was quietly filed away.

Jones’s startling confessions, to crimes both judged and those never tried, remained a secret buried in government files, even as the prospect of her release from prison began to loom.

With “good time” credit, Texas’s mandatory-release law would spring Jones from prison as early as March 2018, at age sixty-seven, after she’d served thirty-four years and eight months of her ninety-nine-year sentence. During more than three decades behind bars, Jones had generally committed only minor infractions. The most serious offense in her disciplinary file occurred in September 2011, when Jones lost sixty “good days” for “threatening to inflict harm on an officer.” Explained a summary of the episode: “Offender stated that she had nothing to lose and the next time she has a problem she was going to kick the officer’s teeth in.”

As the prospect of Jones’s release became known, alarmed family members of the Texas children who had died under her care began to organize. They were aided by Andy Kahan. Kahan was the city of Houston’s crime-victim advocate, a former parole and probation officer skilled at drawing media attention; Jones’s release, he declared, would make her “this country’s first serial killer ever to be legally released.”

The group’s most passionate advocate and informal leader was Chelsea McClellan’s mom, Petti, who had become a nurse herself in the years since Jones’s conviction. Petti spoke often of her belief that if Jones ever got out—even as a senior citizen—she would surely kill again, and of her determination to prevent that. “This is my mission now,” she said. “Losing a child does not consume you; it drives you.” She told me she was fighting for the children who’d died at the San Antonio charity hospital. “None of the babies in San Antonio had any justice. That really bothered me. Those babies were just treated like trash babies. It’s like they didn’t matter.”

In private meetings and press interviews, the family members pressed the Bexar County DA’s office to do the only thing that could keep Jones behind bars: bring—and win—a new murder case against her, for one of the many unexplained baby deaths in the San Antonio hospital’s ICU back in the early 1980s. (There is no statute of limitations on murder.)

By 2014, with the promise of freedom just four years away, Genene Jones was keen on getting out—and was again denying her crimes. According to a summary of her parole interview that year, “the offender expressed no remorse for the present offenses and maintains that she did not commit either of the offenses.” Jones, the summary added, “was interested in her projected release date.” The Texas parole board had signaled the inevitability of her mandatory release in 2018, setting the conditions for Jones’s freedom. It included electronic monitoring and no work or contact with children.

In fact, Jones was plotting to accelerate her release. “I’m excited,” she’d written a friend several months earlier. “If all goes as planned, I could be out by the end of the year.” In June 2014, she petitioned the San Antonio courts on her own behalf, seeking immediate release on a claim that her sentence had been improperly extended, and that she was thus “a free citizen being illegally held in the state of Texas prison system which is cruel and most definitely unusual punishment.” Jones said her “illegal confinement” had “caused mental, physical, emotional and health issues,” for which she was demanding “financial compensation.” Jones’s petition was rejected by year’s end.

As she awaited her freedom, Jones took comfort from a covey of supportive pen-pals—former inmates on the outside and a cluster of prison-ministry evangelicals. Early in her prison term, she’d flirted with Judaism (“I’m leaning toward the Hebrew religion,” she’d told me in 1987 after I noticed the Star of David that had replaced a cross on the chain around her neck). Now Jones was a born-again Christian. Her correspondents exchanged long letters and Christmas cards with Jones, and filled her prison commissary account.

In a taped prison phone call with one of her friends on the outside, Jones exulted about the “big stink” years earlier over the reported destruction of Bexar County Hospital medical records. She believed this would stymie any effort to bring a new murder charge against her. District attorney Susan Reed, commented Jones, “said that she’d take one of those [cases] . . . and keep me in here the rest of my life. Well, now she can’t do that because there’s no records.”

Then in her sixties, Jones complained about prison conditions (“Sodom and Gomorrah everywhere you look”) and wrote often about her latest medical afflictions. She had been issued a walker and was receiving seven different medications. “My health is not good,” she told one friend. “My kidneys are struggling and they have found a malformation in my skull that traps spinal fluid. I am dizzier (than my normal self ), lose my balance, can’t swallow, weak arms, ringing in my ears (not always at once). But God’s grace is sufficient.” She wrote of suffering from gout in both feet, a bowel obstruction, cancer, and a broken kneecap. She passed on news of dire diagnoses (“I was told Monday my heart was failing”) and threatened surgery (“They will cut me from navel to back to see if they have to remove a kidney”).

But the end of her time in captivity was growing closer, and nothing seemed able to stand in the way. “I am going home in 13 months,” she told one correspondent in a pair of letters. “Satan keeps trying to take me out before I leave here.” The believers always wrote back, offering warm reassurance. “I love you, sweetheart,” declared one. “No weapon formed against you shall prosper . . . you are on your way to heaven.”

Some of Jones’s correspondents appeared interested in more than saving her soul. In October 2016, Andy Kahan, the crime-victim advocate, discovered a handwritten Christmas card signed by Jones listed for sale on a “murderabilia” website for $750. It carried a notation from the seller that availability of genuine Genene Jones correspondence was “extremely rare.”

In November 2014, Bexar County DA Susan Reed, seeking her fifth four-year term, was ousted from office. San Antonio’s new DA was a Democrat: Nicholas “Nico” LaHood, a brash, forty-two-year-old criminal defense lawyer sporting suspenders, slicked-back hair, and arms covered with tattoos.

In December 2016, with Jones’s mandatory parole just fifteen months away, assistant DA Jason Goss, a young LaHood deputy (he was in diapers at the time of Jones’s crimes) decided to take on the mission of keeping her locked up. Earnest, aggressive, and ambitious, Goss was a native of Bryan, where he grew up in the shadow of Texas A&M University. He dipped snuff and wore Caiman alligator boots.

In his quest for a new murder indictment, Goss soon zeroed in on the death of eleven-month-old Joshua Sawyer on December 12, 1981, at the height of the pediatric ICU’s mysterious “epidemic.” Sawyer, admitted for severe smoke inhalation after being rescued from an explosion and fire at his family’s small rental home, had shown signs of improvement before arresting twice and dying under Jones’s care. Especially shocking was the lab report documenting a deadly level of Dilantin, the anti-seizure drug, in Joshua’s blood.

Goss and DA investigator Larry DeHaven interviewed Connie Weeks, Joshua’s mother, who was just twenty when her son died. Like many of the ICU’s patients, the little boy had been transferred to the county hospital because his family lacked insurance. “We were very, very poor,” Weeks told me. She recalled how, by Joshua’s fourth day in the ICU, his seizures stopped and he was breathing without a respirator. A friend had talked Connie into taking a break—for a shower, a change of clothes, and a movie at the nearby Galaxy Theater. “I knew he was doing better,” said Weeks. Then an usher came into the darkened movie theater to summon her back to the ICU. Joshua had suffered the first of the unexpected emergencies that led to his death—after Jones had arrived to care for him.

In 2017, after Goss located Weeks—by then fifty-six and employed at a local bank—she handed him an investigative windfall. Weeks revealed that she’d saved her son’s three-inch-thick medical record from three decades earlier. “It’s all I had left of Joshua,” she said later. “Everything else was destroyed in the fire.” The investigators next tracked down a valuable witness: George Farinacci, the hospital lab technician who ran the test revealing the baby’s toxic Dilantin overdose—a reading so high it had initially exceeded the electronic equipment’s upper limit. Farinacci was now working in a San Antonio suburb as a dentist.

By late spring, Goss felt confident he had enough. He went to the Bexar County grand jury on May 25, presenting all his evidence in a single day, starting with a two-hour PowerPoint presentation. He then brought in just a handful of witnesses, including Connie Weeks and Petti McClellan.

Left to deliberate after prosecutors exited the room, the grand jurors took less than two minutes to indict Jones for murdering Joshua Sawyer. Her alleged weapon: a massive overdose of Dilantin. The grand jury then took five more minutes to set Jones’s appearance bond at $1 million, easily enough to keep her behind bars until trial—and well past her mandatory state-prison release date, then just nine months off. As the grand jurors exited their courthouse meeting room, men and women were in tears, and they hugged the waiting mothers. “I’m stunned,” said Petti McClellan afterward. “I didn’t think this was ever going to happen.”

Josh Sawyer was only the start. Less than a month later, the same grand jury indicted Jones for murdering two-year-old Rosemary Vega by injecting her with “a substance unknown” in September 1981. Recovering in the pediatric ICU from a successful heart operation performed by the hospital’s star surgeon, little Rosemary, after being placed on a respirator, experienced breathing problems, then suffered seizures and multiple arrests on the 3–11 shift over two consecutive nights—all under Jones’s care. According to a later internal hospital review, “Nurse G. Jones was in attendance during the final events.”

The girl’s mother had offered Goss’s grand jury a heart-wrenching account of her baby’s demise. Just eighteen at the time, Rosemary Cantu worked in the hospital’s housekeeping department, where her duties included cleaning pediatric ICU rooms. She knew Genene Jones. Cantu told me she had watched the nurse push a drug into Rosemary’s IV line shortly before she went into cardiac arrest. “She walked in with the injection. I saw her and asked her, ‘What was she doing? What are you going to give her?’ . . . She said, ‘I’m giving her something to help your baby rest.’ After she walked out, not two minutes later, my daughter started turning purple. The monitors went off; people started running. She was doing good until Genene injected her.”

A short time after burying her daughter, Cantu quit her job at Bexar County Hospital. “I went back, tried it, and I couldn’t take it.” Cantu was fifty-four at the time of the indictment, with five surviving children and twenty grandchildren. “I’ve been waiting for this moment since my daughter passed away,” she said, on the day the murder charge was handed down. “It just hurts me that I waited so long before somebody would hear me.”

Two more murder indictments followed eight days later. The grand jury accused Jones of killing eight-month-old Ricky Nelson in July 1981 and four-month-old Patrick Zavala in January 1982, in each case injecting the baby with “a substance unknown.” The fifth (and final) new case was handed down on Halloween. It accused Jones of murdering three-month-old Paul Villarreal on September 24, 1981, by injecting him with heparin; while recovering from elective surgery, Paul died during the 3–11 p.m. shift after experiencing unexplained episodes of uncontrolled bleeding. Now charged with the murders of four little boys and one girl, Jones faced a total of $5 million in appearance bonds. Each case was punishable with a life sentence.

With her state prison term running out, Jones, then sixty-seven, was transferred to the Bexar County jail on December 4, 2017. She arrived in San Antonio in red scrubs and handcuffs; her white hair was thin and cropped. She moved slowly, with the aid of a walker. Reporters and cameras greeted her. “Do you plan to plead guilty to these five charges?” one asked, thrusting his microphone to her face. Jones kept her gaze downward and said nothing.

Jones made her first courtroom appearance three days later in a wheelchair, with a surgical mask over her face, and remained silent during her arraignment. She was represented by two court-appointed attorneys: Cornelius Cox, a San Antonio courthouse veteran who began practicing law in 1984, the year of Jones’s original murder trial; and Brigitte Garza, who mixed criminal defense work with her specialty in immigration law. After each of the new murder charges was read, Cox announced on his client’s behalf that she was pleading “not guilty.” She was quickly wheeled out of the courtroom afterward.

Cox spoke to reporters after court, dismissing any talk of a quick plea bargain, making clear he intended to pursue all options in her defense. In fact, Jones had already privately received the only offer she would get from LaHood and Goss, who were eager to take her to trial. It would require her to plead guilty to murder in all five cases, and accept a sentence that would push her mandatory release past her hundredth birthday. It was quickly rejected. “It was a plea offer that wasn’t much of a plea offer,” Cox later told me.

By the spring of 2018, parents pressing for new convictions were in a state of high anxiety. On March 6, DA LaHood, seeking his second term, had been beaten in a bitter campaign for the Democratic Party nomination by defense attorney Joe Gonzales, his onetime law partner and former friend. Gonzales’s likely victory in heavily Democratic Bexar county—and January 2019 swearing-in—seemed certain to displace Goss, a LaHood loyalist whom the families viewed as their irreplaceable champion in prosecuting Jones.

For a time, the parents harbored hopes that Goss could convict Jones of murdering Joshua Sawyer before he left office at year-end. Goss tried to make that happen by offering procedural concessions to Jones’s defense team, including an agreement to transfer venue to any location in Texas. But Jones’s lawyers were happy to run out the clock, clearly believing she’d fare better when Goss, the man who had pieced together the five new murder cases, was gone.

Gonzales dismissed the notion that Goss was indispensable. “There are certainly other prosecutors as competent as he is to handle such cases,” he told me. After taking office in January 2019, the new DA assigned a pair of experienced deputies to handle the Jones prosecution: Catherine Babbitt, his head of major crimes, and assistant DA Samantha DiMaio, who had a personal history with the Jones case. She was the daughter of Dr. Vincent DiMaio, the former chief county medical examiner who was the first to alert the DA’s office about Jones back in 1983. “I’ve lived it for a very long time,” she noted.

By July, they’d secretly teed up a deal. Jones, who was loath to formally confirm her status as a “serial killer,” wouldn’t acknowledge a single new murder. Instead, she would plead guilty in all five cases to injury to a child with intent to cause serious bodily injury. The resulting fifty-year sentence would likely send her back to prison for the rest of her life. “In our minds, it would accomplish the exact same thing” as a murder plea, said Babbitt. “And in Genene’s mind, she would not be known as a serial killer.”

The agreement was so far along that Babbitt and DiMaio had already held a private meeting with the wary families to sell them on it. Eager for everything to go smoothly, lawyers for the two sides also decided to take the unusual step of first presenting the agreement to the presiding state district judge, Frank Castro, informally, rather than in open court. But after Castro ushered Cox and DA Gonzales into his chambers for the private meeting (leaving Babbitt waiting outside), he told them he wouldn’t approve the deal. Babbitt recalls that Gonzales emerged looking “a little defeated,” informing her that the judge wouldn’t accept less than a murder plea from Jones. “In his head, she was a baby-killer, not a baby-injurer,” said Babbitt. “I guess the semantics of it made a difference to him.”

Once again, it seemed, Genene Jones would be going to trial.

By New Year’s Day 2020, Bexar County’s prosecutors were making their final preparations to try Genene Jones, then sixty-nine, for murder. During their year on the case, Catherine Babbitt and Samantha DiMaio had gradually won the parents’ trust and steeped themselves in the story of Josh Sawyer’s death—by far, in their view, their best shot at convicting Jones. The evidence for her prosecution had grown to forty-two boxes.

On January 6, DiMaio sent the defense team two pretrial documents spanning Jones’s tumultuous life. The first was the state’s witness list for the Sawyer trial. It contained 267 names. The second was a laundry list of “extraneous offenses”—notice of all the “crimes, wrongs, and acts” that the state was prepared to use to convict Jones. It included ninety-six separate items, including claims that she had murdered twenty-four children. The last item on the list: “on or about” 1977, Jones had “committed the offense of Aggravated assault by holding a gun” to her mother’s head.

Cornelius Cox called Babbitt later that day: Genene wanted to make a deal.

The details rapidly fell into place. Jones would plead guilty to murdering Josh Sawyer “with a deadly weapon” and receive a life sentence. The other four charges would be dismissed, but each family would be allowed to give a victim-impact statement in court, directly addressing their child’s alleged assailant. Jones would receive a life sentence, requiring her to serve twenty years before ever becoming eligible for parole. With credit for time she’d already served awaiting trial, that would keep her behind bars, at minimum, until December 3, 2037, when she would be eighty-seven years old. It was virtually certain that she would die in prison, fulfilling the goal of her victims’ aging parents.

It was over in thirteen minutes. Genene Jones, dressed in blue scrubs, pushed her walker into the courtroom on the morning of January 16, 2020. After confirming her guilty plea in a raspy whisper, she watched—but remained silent and expressionless—as the presiding judge, and then tearful family members, assailed her for her crimes.

For those who had waited decades to attain any measure of justice in the deaths of their loved ones, the case remained an emotional roller-coaster. Connie Weeks, Joshua Sawyer’s mother, sternly told Jones: “I’m glad today that you will never see daylight as a free woman and your life will end in captivity for killing my son.” Standing just feet away from her child’s killer, Weeks concluded, “I will leave you with this: I hope for you to live a long and miserable life behind bars. Goodbye.”

After the formal proceedings were over, Jones stood up, glanced at the back of the courtroom, and quickly wheeled herself out a side door.

A few months later, Bexar County’s chief medical examiner notified the DA’s office that she would legally amend the Texas death certificates for the five children. Joshua Sawyer would be listed as a victim of “homicide.” The cause of death for the four other children would be memorialized as “undetermined.”

Peter Elkind is a former associate editor of Texas Monthly and coauthor of The Smartest Guys in the Room: The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron. He lives in Fort Worth. Excerpted from The Death Shift: Nurse Genene Jones and the Texas Baby Murders (Diversion Books). Copyright Peter Elkind, 2021.

- More About:

- San Antonio