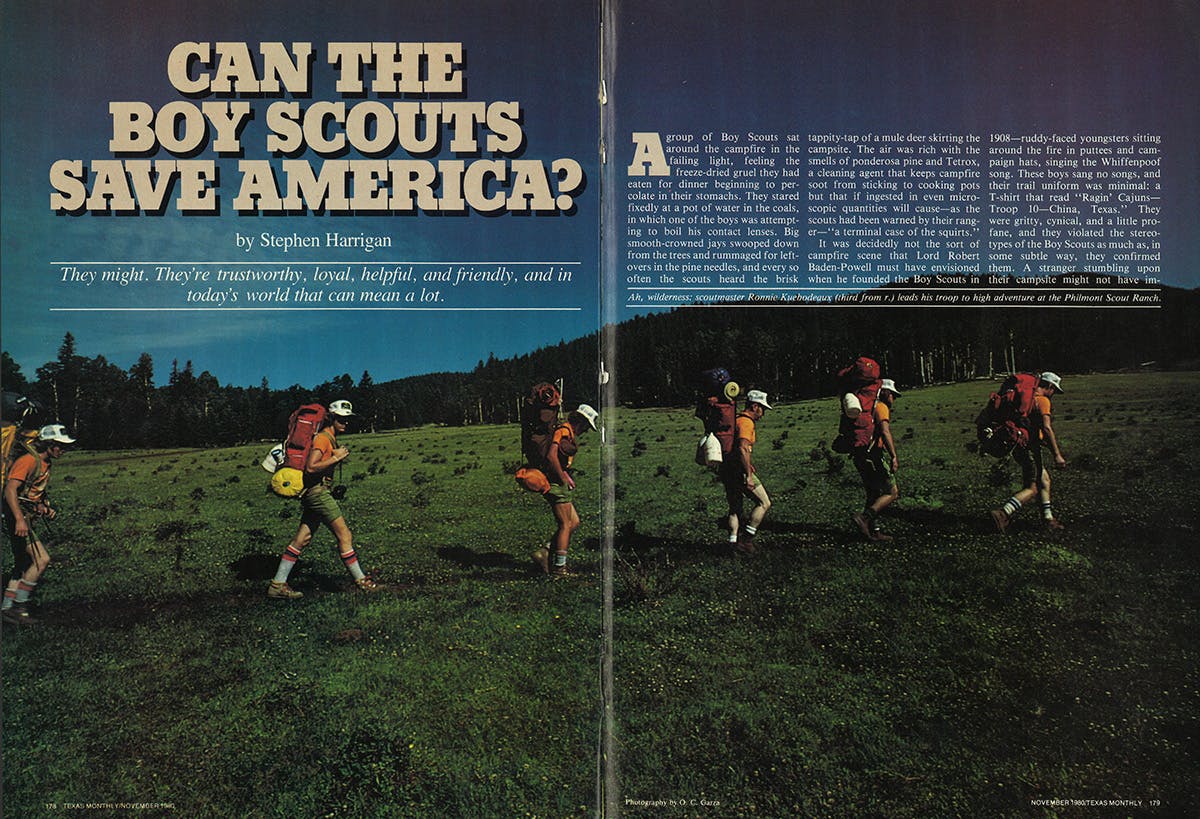

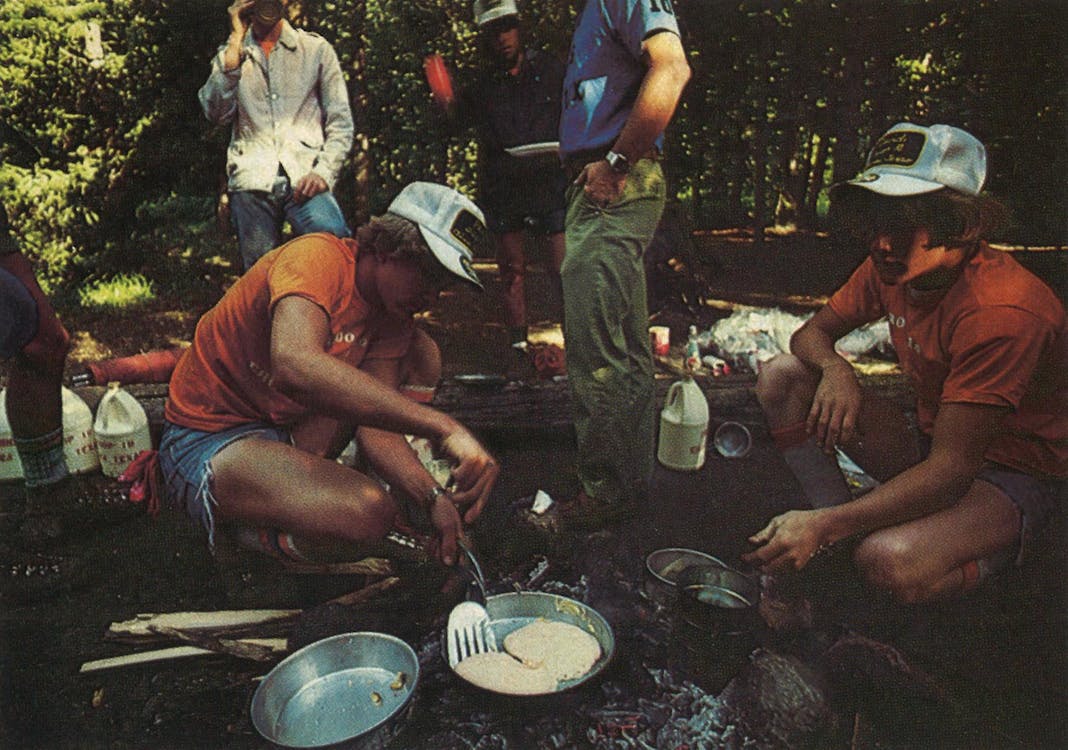

A group of Boy Scouts sat around the campfire in the failing light, feeling the freeze-dried gruel they had eaten for dinner beginning to percolate in their stomachs. They stared fixedly at a pot of water in the coals, in which one of the boys was attempting to boil his contact lenses. Big smooth-crowned jays swooped down from the trees and rummaged for leftovers in the pine needles, and every so often the scouts heard the brisk tappity-tap of a mule deer skirting the campsite. The air was rich with the smells of ponderosa pine and Tetrox, a cleaning agent that keeps campfire soot from sticking to cooking pots but that if ingested in even microscopic quantities will cause—as the scouts had been warned by their ranger—“a terminal case of the squirts.”

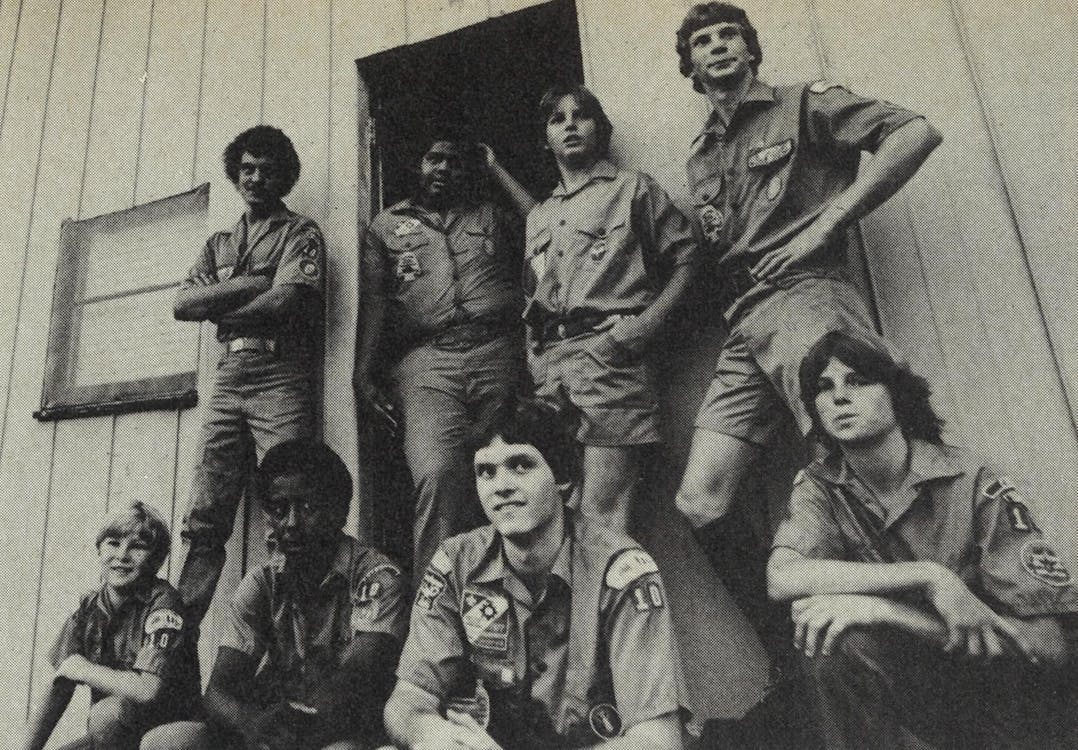

It was decidedly not the sort of campfire scene that Lord Robert Baden-Powell must have envisioned when he founded the Boy Scouts in 1908—ruddy-faced youngsters sitting around the fire in puttees and campaign hats, singing the Whiffenpoof song. These boys sang no songs, and their trail uniform was minimal: a T-shirt that read “Ragin’ Cajuns—Troop 10—China, Texas.” They were gritty, cynical, and a little profane, and they violated the stereotypes of the Boy Scouts as much as, in some subtle way, they confirmed them. A stranger stumbling upon their campsite might not have immediately taken them for Boy Scouts, but neither would he have taken them for just an ordinary group of boys. They had collective qualities of efficiency and harmony that could only have come about through training and a sense of tradition.

Besides the T-shirt, each scout had a gimme cap with his first name embroidered on the crown. Their names were George, Andy, Scott, Phil, Lanny, David, and John. Their scoutmaster’s name was Ronnie Kuebodeaux, and they called him Mr. Ronnie.

China is just a few miles west of Beaumont and far away from this mountain meadow high in the Sangre de Cristo where Troop 10 had stopped on the first day of their ten-day backpacking trip through Philmont Scout Ranch. They had had an easy four-mile walk in from base camp and had spent most of the afternoon setting up their tents and playing Frisbee in the meadow. Now the thin mountain air had finally sapped their energy. They were drowsy, and I noticed that the boys who had applied the Tetrox to the pots kept unconsciously rubbing their fingers on their pants legs. Here at Philmont every scout had two secret fears: one was getting troxed, and the other was getting eaten by a bear.

Philmont is the best known and most spectacular of the five “high adventure bases” owned and operated by the Boy Scouts of America. It consists of 215 square miles of northeastern New Mexico that was deeded to the Boy Scouts—along with an office building in Tulsa—by oil millionaire Waite Phillips. Every summer 15,000 scouts from all over the country come here to wander Philmont’s mountain trails and participate in the various programs—rock climbing, panning for gold, shooting black-powder rifles—offered in its 23 backcountry camps.

Kuebodeaux and about half of his group had been to Philmont two years earlier, and they returned this summer determined to follow the “super-strenuous” itinerary, a route that would take them 109 miles, through a dozen high mountain passes and to the top of every major peak in the ranch. The few groups they had met so far on the trail were composed of pale, skinny, scowling kids who looked like they had spent the last few years in a dark room playing Dungeons and Dragons. Their scoutmasters, who seemed to sputter in and out of cardiac arrest, were appalled when Kuebodeaux told them his group’s plans; they practically begged him to reconsider. But Troop 10 paid them no mind; they were afflicted with Cajun machismo.

Tonight the scouts were camped at seven thousand feet. Until the last mile or so of their hike they had been within view of the base camp and its sprawling tent city, where they had slept the night before. There was a mess hall down there as well, and a trading post, four chapels, a laundromat, and various administration buildings, all dominated by a gigantic, gloomy slab of intrusive rock known as the Tooth of Time.

Ronnie Kuebodeaux stood outside the small circle of the campfire holding a cup of coffee in his hand, grinning to himself. He was a scoutmaster of the irrepressible school, the kind of guy who would think it the funniest thing in the world if all of the troop’s tents got blown over by a hailstorm at three in the morning, which at Philmont is a likely occurrence. But for all that, Kuebodeaux had his serene moments as well, and he possessed a quiet, plodding sort of endurance. He had as his foil and fellow adult leader a friend from China named Cotton Waldron, Phil’s father. Waldron was heavier and less agile than Kuebodeaux, and he suffered through the uphill grades with a crestfallen expression on his face.

But now that he had his pack off his back and his feet out of his shoes and could wiggle his toes in the cool air, Waldron was just fine. It was dark now, and occasionally someone would lean down and fan the coals with a Frisbee. The talk was routine Boy Scout campfire talk, which is to say it consisted almost exclusively of jokes about farts.

Brrrrrrrrrrrt!

“Yow! Get that boy some asbestos underwear!”

“It wasn’t me! I swear to God! It was him!”

By and by the conversation swung over to the subject of bears. Phil Waldron and David Mitchell had found a deer carcass not far from camp when they were looking for firewood. Phil judged that it had been dead for four days, and David, in an equally sober demonstration of scout-craft, deduced that since there were no “kick marks” near the deer it had died quickly. Ergo, it had been killed by a bear.

Rob Smith, the Philmont ranger who had been assigned to the group for their first few days on the trail, perked up when he heard the bear talk. He was about twenty, smoked a little woodsman’s pipe, and had a gangly, solitary look, like the young Thoreau. He presented his axiom. “If a bear ever chases you,” he said, “run downhill.”

This was not strictly idle talk. There are a lot of black bears in residence at Philmont, many of whom have attached themselves on a more or less permanent basis to a particular camp, where they are regarded as both nuisance and totem. The bears lumber through the camps at night, hungry for a Rich-Moor trail mix dinner but willing to settle for toothpaste or shaving cream. There are stories of bears clawing their way through a tent to get at the Chap Stick in a scout’s pocket. To avoid this, campers must put all their food in burlap bags and string it up high between the trees.

Troop 10 was not all that afraid of bears. John Sanders was thirteen, the minimum age at which Philmont will accept scouts, but the rest were well along in high school, and eighteen-year-old Scott West was scheduled to report for Marine boot camp two weeks after he returned home. They were not really kids, and they were not the kind of city scouts that Smith had guided before, who mistook cows for deer and kept asking where the camp refrigerator was located. Nevertheless, the Ragin’ Cajuns had a healthy sense of apprehension, which was heightened by the dark, confining forest.

“Now, if you see a rattlesnake on the trail,” Smith spoke up again, “leave him alone. But if he crawls into your sleeping bag go ahead and kill him.”

The scouts accepted this sanction without comment. Smith went on to say that he knew a lot about snakes because he was a member of the Fang Finders, a snake-handling club. “I have been known to drive down the street on my motorcycle with several king snakes coiled around my arms,” he said.

The fire burned down rather quickly, and no one seemed much interested in building it up again. Soon most of the scouts went to sleep in the two-man backpacking tents they had been issued at base camp.

I went to my own tent and lay on top of my sleeping bag, reading the latest edition of the Boy Scout handbook by flashlight. It was smaller than the handy pocketsize edition I’d had when I was a scout, and I missed the cover of that earlier handbook, which featured a wraithlike Indian appearing in the smoke of a campfire, proud and protective of the three Boy Scouts sitting cross-legged on the ground. This edition has a peppy Norman Rockwell painting—his “Calling All Boys” phase. But I was glad to have it along; it is such a benevolent volume. The new handbook was written by William “Green Bar Bill” Hillcourt, author of the now-classic 1944 Scout Field Book and a Boys’ Life columnist for fifty years, as well known to the readers of that magazine as Whittling Jim or Pee Wee Harris. I turned to the introduction, which was titled “Your Life as a Scout.”

“Today you are an American boy,” writes Green Bar Bill. “Before long you will be an American man.” That was certainly true. My own experience confirmed it. Seventeen years ago—seventeen years!—I had come to Philmont as an “American boy,” as a scout. We had traveled the way Boy Scouts traveled then, not in airplanes or good-time vans but in a dilapidated school bus, spending the night along the way in vacant hangars on Air Force bases. We had arrived at base camp in an early-morning fog from which the Tooth of Time protruded like some monstrous primitive altar. I had immediately thrown up.

The idea of wilderness was something that, as a Boy Scout, I knew I ought to be thrilled about, but the fact was that after a one- or two-day camp-out I usually came home feeling like a mountain man returning to rendezvous after two years alone in the Rockies. I was the sort of Boy Scout who would fulfill the requirements for the Hiking merit badge by walking downtown, watching Journey to the Center of the Earth, and then hiking back home carrying a box of popcorn and a Coke as a trail snack. The prospect of two weeks in those fog-shrouded mountains alarmed me, but no more, I suppose, than it did the rest of my road-weary flatland troop.

We were issued our trail food (the only particular item I can remember is a product known as Bif, which was a poor man’s version of Spam) and our “tents,” which were square tarpaulins without poles or ropes or eyelets that we were supposed to figure out how to set up.

Things were miserable for the first few days. We would sit under our tarps in the rain, holding them up with a single stick and swilling Pepto-Bismol. We were pelted by hail, harangued by our ranger for being such whiny sluggards, and tormented at night by the cold, which penetrated our official Boy Scout sleeping bags as if they were gauze.

Suddenly things started to work out. The weather cleared, for one thing, but we also found ourselves transformed from acrimonious, self-centered kids to members of an efficient unit. We delegated and accepted authority; we said the Philmont Grace before meals and sang “Sippin’ Cider Through a Straw” and “John Jacob Jingleheimer Schmidt” as we hiked along the trails. It was as if the ghost of Lord Baden-Powell himself had appeared among us to rally our sagging spirits —“Best foot forward, lads! That’s the ticket! What a smashing time we’re having of it, eh?”

I remembered now with amusement the ardor of my homesickness in those early days, the sense that I had ended up at Philmont completely by accident. I had never planned to become a Boy Scout, it was simply something that boys in my community did. I had passed through the program, from Cub Scouts to Explorers, in such a distracted fashion that it surprises me how rich the whole experience now seems and what a peculiar store of knowledge and skills it has left me. To this day I can tie a taut-line hitch, measure the height of a tree or the breadth of a river by sight, start a fire with flint and steel, tell poison ivy from poison sumac. I still retain snatches of Morse code and semaphore signals, and in an emergency I could probably construct a monkey bridge or an observation tower out of logs and twine.

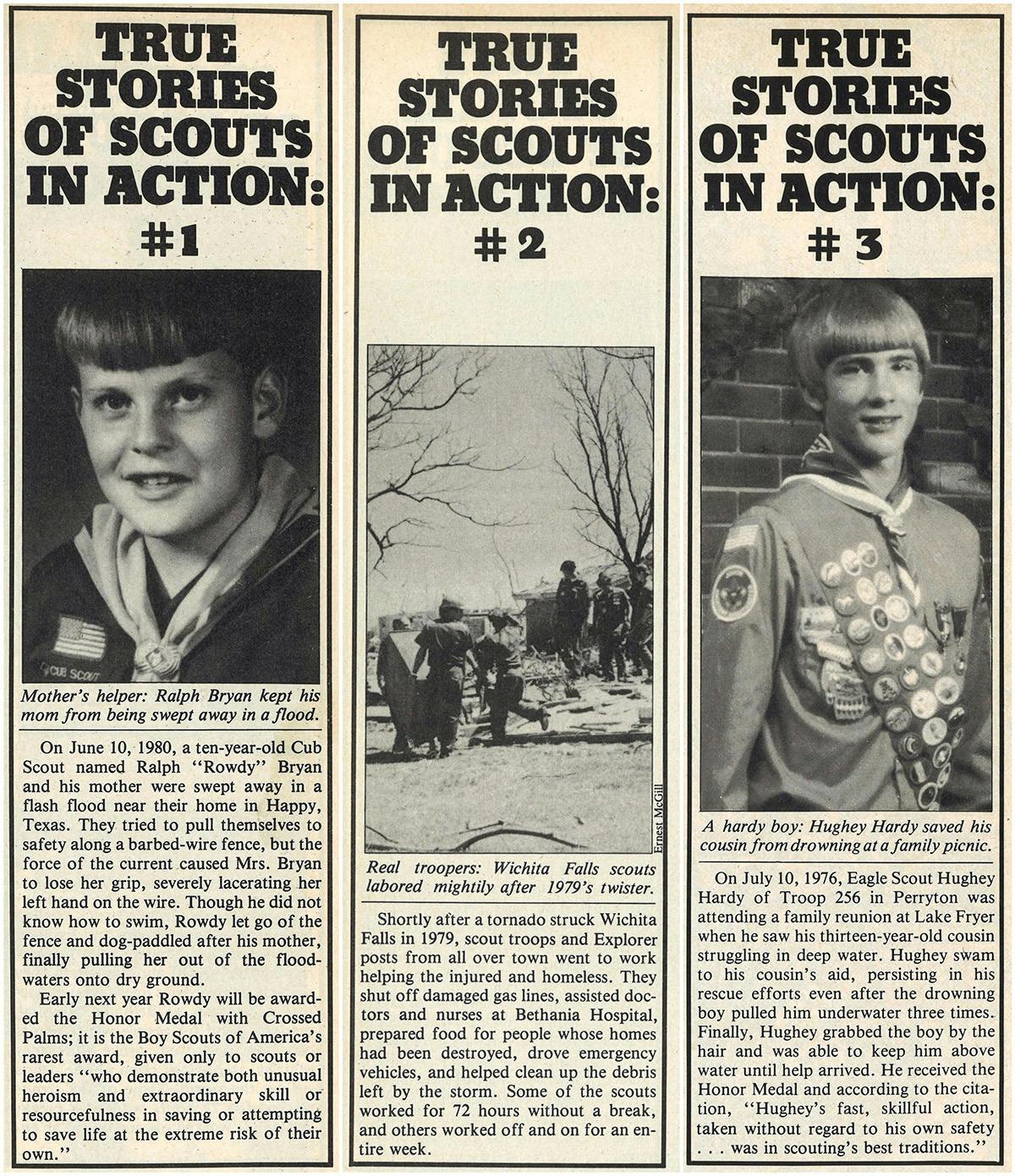

For years my life was crowded with scout functions: troop meetings, patrol meetings, Order of the Arrow ceremonies, summer camps, courts of honor, and sessions with merit badge counselors, volunteer pillar-of-the-community types who would sit in their book-lined dens nodding indulgently while I told them what I had learned about soil and water conservation or first aid to animals. I attended camporees, scoutoramas, and a national jamboree where the trading of patches was as furious as the commodities exchange. I cooked fish sticks on an open fire; I dug expended slugs from the rifle range at camp, melted them down over the fire, and made “brass knuckles” by pouring the resulting slag into molds I’d scooped out in the dirt. And I waited for the day—prayed for it—when I would be called upon to rescue someone who had fallen through ice, or to stop a gushing artery with my bare hand, or to pry an electrocution victim from the fuse box with a broom handle. When that day came some scout functionary, perhaps even the president of the United States himself, would pin a medal on me and my exploits would be depicted in comic strip form in the pages of Boys’ Life—“A True Story of Scouts in Action.”

The Boy Scouts had been a way of life for me and millions of other boys, and though as a jaded near-adult I had been guilty of belittling the movement, lately I had found myself rising to its defense. The Boy Scouts are corny, they can easily be made to seem ridiculous, and the principles of scouting, like the principles of the New Testament, can be warped and exploited. But the scout oath is a pure and formidable statement—a pledge to keep oneself “physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.” The Boy Scout movement is not just a “game,” as Baden-Powell insisted on calling it. It is an unabashed moral system.

General Baden-Powell, or B-P, as scouters reverently refer to him, was the very embodiment of British colonial pluck. In some ways he resembled other British heroes like Chinese Gordon or T. E. Lawrence, but he does not seem to have had their mystic bent or their grain of madness. He began as a young officer with the gentlemanly talents of sketching, writing, and acting, with a deep love of woodcraft and an indomitable nerve. He was as bred to the military life as the horses he rode into battle. “I enjoy this business awfully,” he wrote to his mother from the Afghan front. He seemed to love the courtesy and grace he was able to bring to the carnage of war and blood sports. While stationed in India he became so excited about a local activity called pigsticking, in which one lanced wild boars from horseback, that he wrote a book on the subject. He taught his men the fundamentals of scouting, how to move stealthily and silently through enemy territory, how to read animal tracks and live off the land. He admired his enemies—whether they were Zulus or Afghanis or Dutch Boers—and he appeared happiest when engaged with them, in the noble gamesmanship of war.

General Baden-Powell, or B-P, as scouters reverently refer to him, was the very embodiment of British colonial pluck. In some ways he resembled other British heroes like Chinese Gordon or T. E. Lawrence, but he does not seem to have had their mystic bent or their grain of madness. He began as a young officer with the gentlemanly talents of sketching, writing, and acting, with a deep love of woodcraft and an indomitable nerve. He was as bred to the military life as the horses he rode into battle. “I enjoy this business awfully,” he wrote to his mother from the Afghan front. He seemed to love the courtesy and grace he was able to bring to the carnage of war and blood sports. While stationed in India he became so excited about a local activity called pigsticking, in which one lanced wild boars from horseback, that he wrote a book on the subject. He taught his men the fundamentals of scouting, how to move stealthily and silently through enemy territory, how to read animal tracks and live off the land. He admired his enemies—whether they were Zulus or Afghanis or Dutch Boers—and he appeared happiest when engaged with them, in the noble gamesmanship of war.

Baden-Powell’s supreme moment as a soldier came during the Boer War, when he was in command of a garrison besieged by the enemy in the town of Mafeking. In 1899 the British military was making a dreary showing in the Transvaal; the Boers beat them back on almost every front. But B-P managed to hold out at Mafeking for seven months, confounding the enemy and maintaining the morale of the town’s citizens during consistently heavy shelling and short rations. Baden-Powell convinced the Boers that there was a mine field around the perimeter of Mafeking when in fact there wasn’t; he had a cannon made from scrap metal and rather odd-tasting desserts made from toiletries; he printed his own money and postage stamps, sang Gilbert and Sullivan arias for the amusement of the besieged, and went out by himself under cover of darkness, gathering intelligence from deep within the Boer lines.

While he was under siege at Mafeking Baden-Powell also found time to read the proofs of a book he had written called Aids to Scouting, a little volume he thought might be useful to his troops. When the town was finally relieved B-P discovered that not only was he at the center of a patriotic frenzy back in London but also his modest little how-to book was a best-seller.

It was boys, not soldiers, who took Aids to Scouting most to heart. Boys in England and America were a vast, clamoring horde begging to be turned into scouts. Many men had already tried to satisfy this clientele, and no doubt there were many more who were ready to exploit it. In England there was something called the Boys’ Brigade, whose members wore uniforms and performed military drills, and in America there were, among other such groups, Ernest Thompson Seton’s Woodcraft Indians and Dan Beard’s Sons of Daniel Boone. The Boy Scout movement already existed, in effect, but in a hundred little pieces. It took Baden-Powell to put them together.

In 1907 he organized a week-long experimental camp at a place in Dorset called Brownsea Island. He picked the 21 boys himself, divided them into four patrols, and taught them how to tie knots and stalk and cook out in the open. The Brownsea Island prototype was a great success. To follow it up Baden-Powell published a new edition of his famous handbook, calling it Scouting for Boys.

The Boy Scouts came to America by way of the Good Turn in the Fog incident, which is to scouting what Saul’s conversion on the road to Damascus is to Christianity. In 1909 a Chicago publisher named William D. Boyce lost his way one night in a thick London fog. A boy materialized—we do not really need to credit the report that he “saluted smartly”—and offered to guide Boyce to his destination. When they arrived, the publisher offered the boy a shilling, which he refused, saying that he was a scout and that a scout does not accept money for doing a good turn.

The Unknown Scout—as he is now called in the literature—explained scouting to Boyce and took him to Baden-Powell’s office, then disappeared. It was Boyce who, in 1910, after much legalistic wrangling and merging of various boys’ groups, incorporated the Boy Scouts of

America. In 1926 the BSA awarded its first batch of Silver Buffalo awards for distinguished service to boyhood. The first one went to Baden-Powell, and the second one went to the Unknown Scout.

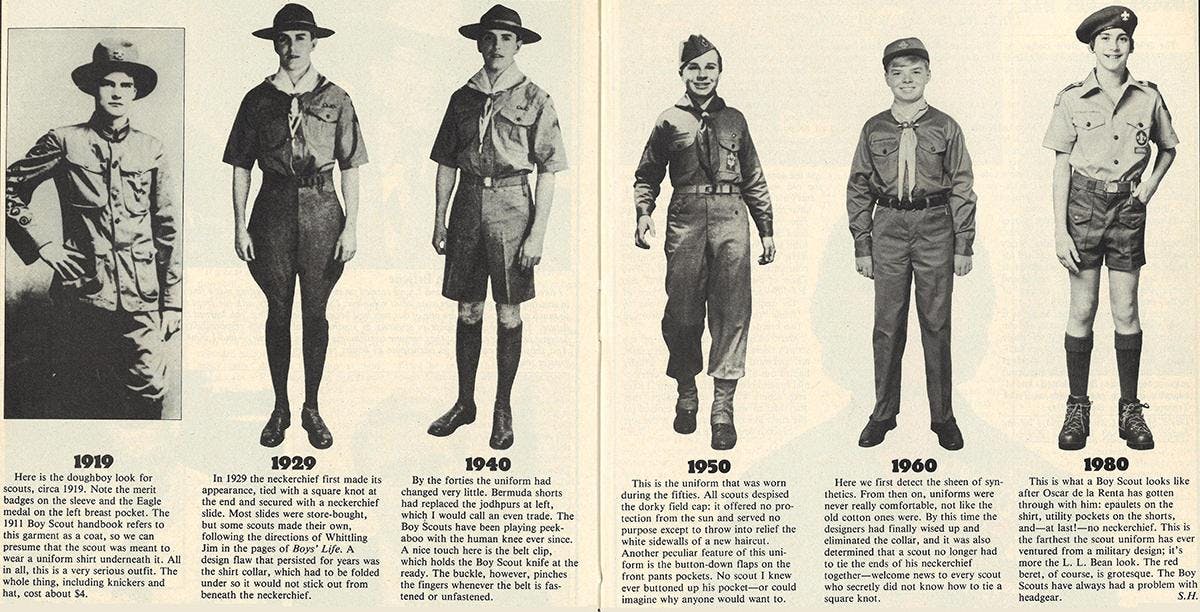

The BSA was a hit from the start. Scouts wore the same sort of khaki expeditionary uniform that British scouts wore. The first American handbook advertises official Boy Scout underwear (50 cents the set) as well as the famous scout knife and the official shoes, big ugly clodhoppers that sold for $2.50 a pair.

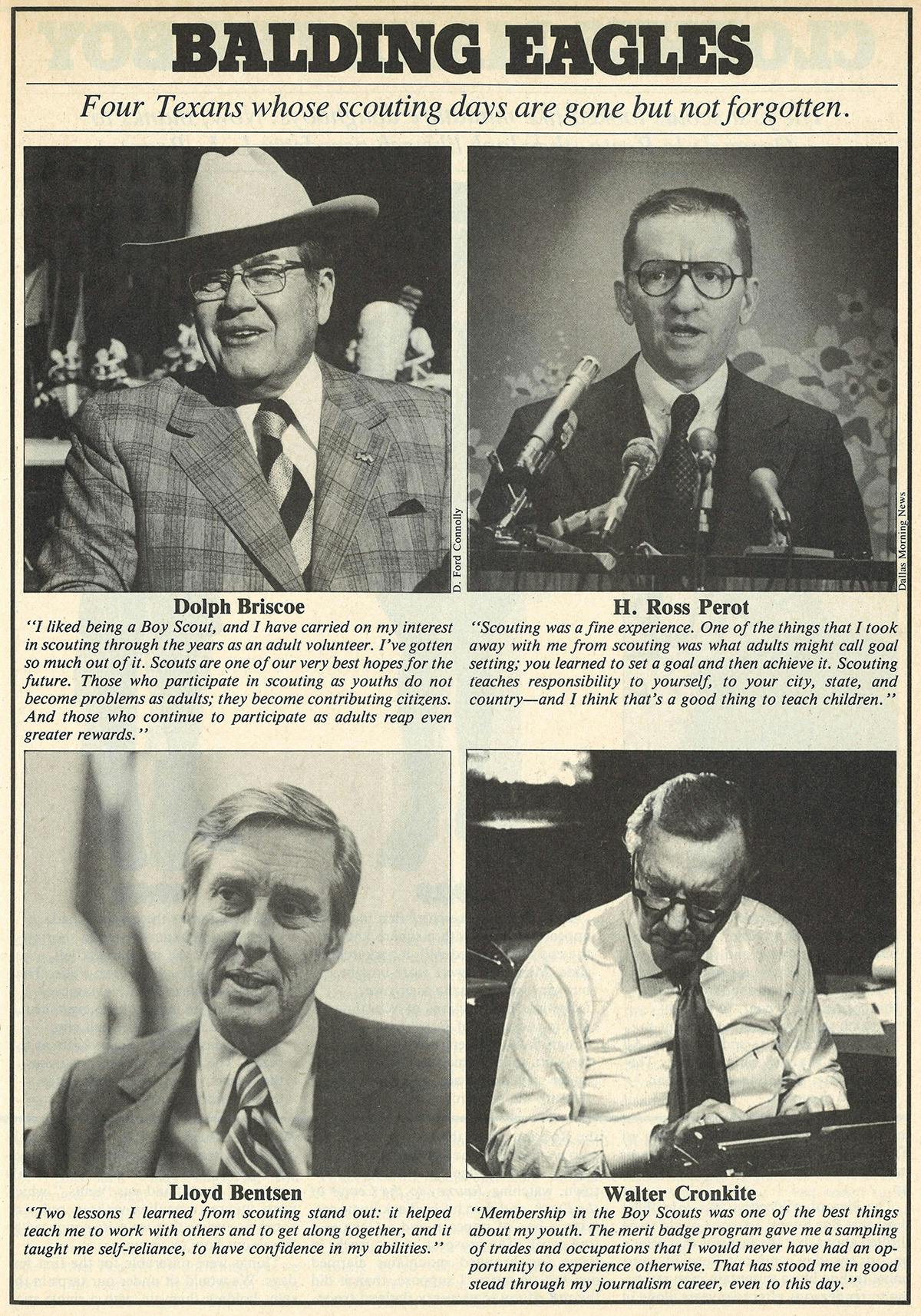

The U.S. Boy Scouts drove ambulances during the 1918 influenza epidemic, they helped out in tornadoes and earthquakes, they collected food and clothing during the Depression and gathered 30 million pounds of rubber during World War II. New editions of the handbook were published, uniforms were changed, merit badges added or deleted. Membership climbed steadily until 1972, when it began to fall off from a peak of 2.4 million scouts. The decline has been consistent and rather severe. In 1979, for instance, fewer than 1.5 million Boy Scouts and Explorers were registered at the end of the year.

Where did they all go? “One of the most obvious things,” says J. L. Tarr, the chief scout executive, “is that there’s been a big decrease in the youth population since 1972. At the same time there’s been an increase in sports participation. Dallas County alone has sixty thousand kids in organized soccer leagues, and then you have competition from the Little League, the YMCA, 4-H clubs as well. The rise in the number of single-parent families decreases the time that parents have to get involved in this kind of program. Another thing that’s obvious to me is that home, church, and school are under a lot of pressure now, and they’re the very institutions that have traditionally been the allies of the Boy Scouts.

“But I think the Boy Scouts were destined more for this time than for 1910. Most of the messages kids are hearing today are ones they don’t need to hear. What they need is a sense of honor, patriotism, duty to God.”

Tarr works out of a big paneled office in the national headquarters, which recently moved from New Jersey to a futuristic industrial park called Las Colinas near the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport in Irving. On the day I visited him he was wearing a blazer with a scout emblem on the pocket and sitting underneath a painting by Norman Rockwell. He kept looking out at the Las Colinas prairie, which was barren except for carefully groomed copses of mesquite. “I saw a hawk out there this morning,” he explained. “I was hoping he might come back.

“I’m a product of the Boy Scouts of America,” Tarr told me, swinging his chair around from the window. “I’m the first chief scout executive that was a Cub Scout. Next year I’ll have fifty years as a registered scout. As a boy I wanted to be a member of the national staff. I went on to college knowing that this was what I wanted to do.”

He spoke mostly in homilies—the pressures on young people today, and so on—but he struck me as a shrewd man who had simply decided where the line should be drawn. I asked him if homosexuals could be scoutmasters. Flat-out no. What about atheists? No again, since every scoutmaster must sign a declaration of religious principle. Well, then, can Moonies be scoutmasters? Tarr swallowed hard and implied that they could as long as they would sign the declaration, but it was decidedly a worst-case scenario.

In other areas the Boy Scouts are a little trendier. The Explorer program, for scouts fourteen through twenty, was recently opened to girls, but there is no truth at all to the rumor that the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts have merged. There are programs for handicapped scouts, deaf scouts, and “Lone Scouts,” boys who live far from any organized scouting activity. The organization has a strong inner-city presence and is making an active drive to recruit Hispanics. And of course there are the new uniforms, designed by Oscar de la Renta.

“Thank you for being interested in the Boy Scouts of America,” J. L. Tarr said as I left to tour the rest of the building. There were five stories to it, each filled with cheerful modular offices. I noticed quite a few old scouter types around—the kind of people you always see at scout functions wearing Baden-Powell moustaches and Silver Beaver badges and short pants and socks complemented by official red garter tabs. Other, younger staffers talked about Club Med and singles apartments in Dallas. When I was introduced to an associate editor of Boys’ Life I decided against asking him about the earring in his left ear.

It all happens in Irving. Here is where scout literature is written, membership fees are collected, jamborees planned, applications processed. The program that this office administers is a kind of franchise operation. The Boy Scouts of America has chartered 414 local councils, staffed mostly by volunteers, which in turn handle the administrative details of their own troops and activities. Each troop has a sponsor—usually a church or school or civic organization. (In the case of Troop 10 it is a China business called M&M Air Service.) Each scout pays an annual registration fee of $2, and local councils receive money from the United Way, among other sources.

By and large the system works well, but a boy’s scouting experience is essentially a potluck affair. If the troop he joins has a strong sponsoring institution that takes the responsibility for finding quality leadership, his life may be utterly changed. But if the unit is a haphazard one, with low morale, few outdoor activities, and a real drip of a scoutmaster, a boy will most likely stay in only long enough to waste his money on a uniform he’ll never wear.

There are other problems. For certain types of people, the Boy Scouts of America is nothing more than a vast exploitable resource. In 1977, for instance, licensed scoutmasters in New Orleans were convicted of sexually abusing the boys in their troop, and it was believed that the men were part of a network that operated in as many as thirty states. In 1974 the registration of thousands of nonexistent scouts caused a national scandal, and just a few months ago law enforcement agents in Virginia used a group of Explorers in an undercover investigation of the sale of alcohol to minors. The national office runs a cursory security check on applicants for scoutmaster or assistant scoutmaster positions, but a system that involves more than half a million adult leaders can hardly guarantee against such crimes and abuses, which were described to me, with considerable restraint, as “unscoutsmanlike behavior.”

Before dawn on the second morning of the trip Kuebodeaux was up and dressed and prowling around the campsite. “Ça c’est bon, ” he was saying. “Rise and shine!” I rolled over in my sleeping bag and looked at my watch. It was five o’clock.

The troop had changed into a different color of Ragin’ Cajun T-shirts. Most of them wore scout shorts, though a few wore blue jean cutoffs whose hip pockets bore the circular impressions made by Skoal cans.

The scouts were packed by six o’clock, their backpacks leaned against each other in the center of camp in an orderly, self-supporting row. “Okay,” said George Bieber, who was the group leader. “We’re gonna police the area.”

As group leader, George was responsible for most of the details of day-to-day life. When a trail forked unexpectedly, the direction the troop took was his decision. He told the scouts who was to cook and who was to wash dishes, who was to hoist bear bags and who was to get water. He did not seem comfortable giving orders, but he had an easy, confident demeanor that was a form of leadership in itself. He was in superior shape, in the habit of burning off excess energy at the end of a grueling uphill climb by doing push-ups with a full backpack.

I walked through the campsite with them but could not find any trash. Except for a few hot chocolate packages that had not burned in the fire, the place was inviolate.

Rob Smith bent down to the cold fire and demonstrated how it was to be put out. He worked on it for ten minutes, pouring on several quarts of water and kneading the dead coals and ashes with his fingers, finally ending up with a gray soupy mass. He stuck a stick straight up in the remains of the fire to indicate to the next group of campers that it had been thoroughly extinguished.

George and Kuebodeaux studied the topographical map, taking bearings from it for the first stage of today’s hike. We were going to Beaubien, a big cow camp six miles away. To get there we would have to go up to Crater Lake, over Fowler Pass, and through a lush, narrow valley known as Bonita Canyon.

The group set off at six-thirty in a neat, evenly spaced line. The orderly tramp tramp-tramp of our progress awakened the other scouts who had stayed in the area. They poked their heads blearily out of their tents and stared at Troop 10 as if it were a circus parade.

“What is a Ragin’ Cajun?” some kid with a New Jersey accent asked. No one bothered to answer him.

We stopped for a cold breakfast about a mile ahead and then walked uphill for another hour until we came to Crater Lake, which is a small scum-covered pond fronting a log cabin. The camp was staffed by a group of young men who wore beaver hats and nineteenth-century work clothes and whose mission it was to recreate for the Boy Scouts the atmosphere of an old-time logging operation.

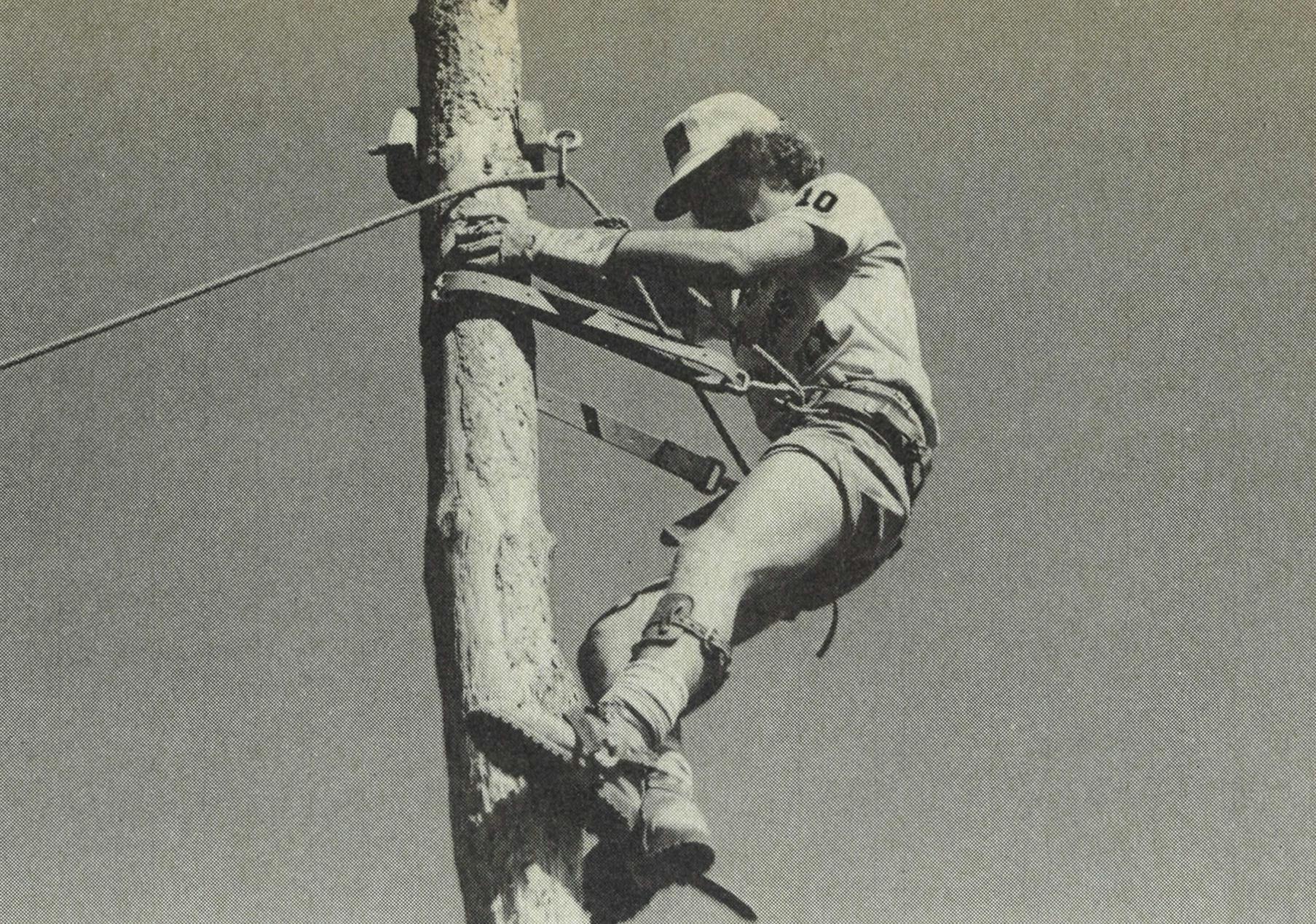

One of the staffers walked the troop down to a little clearing dominated by three thirty-foot poles made from stripped tree trunks. Yawning, he attached climbing spikes to his feet, wrapped a safety belt around the pole, and proceeded to climb to the top, lecturing on the technique all the way. When he reached the top he kissed the eyelet that his rope was threaded through, yelled “Shooocooooder!” at the top of his lungs, then took an apple out of his back pocket and ate it while he admired the scenery.

When he finally came down he let the scouts try it. They went up one by one, punching the heavy spikes into the denuded tree, making ungainly and exhausting progress, until finally they were able to haul themselves the last few inches to the top, where they performed the ritual of kissing the eyelet and yelling “Shooocooooder!” themselves.

After the pole climbing there was another demonstration, conducted in the appalling late-morning heat, of how to hew a log using an adze and increment bore and other quaint tools. “Knots are going to give you problems,” warned the lecturer, who wore a long-underwear shirt and suspenders and had an appropriately rangy appearance. He proceeded to plane the knot on a log, in perfect silence, for a full five minutes. The scouts took off their hats and wiped their brows with their forearms, slapping at the horseflies that nibbled on their bare legs. “A Scout Is Courteous,” they were no doubt thinking to themselves, while the logger hacked away, absorbed.

It was almost noon before we were climbing again, up the steep switchback trail that led to Fowler Mesa. It was not an easy ascent, and when we finally made it over the pass we eagerly ditched our packs in the meadow grass and ate the oily turkey spread some scout nutritionist had decided would make a nice lunch for a group of hungry boys. There were crackers and cookies as well, and some sort of weird chewy candy that was supposed to quench your thirst, and the ever-present orange- or grape- or lemon-flavored bug juice. After lunch John Sanders took off his boots and socks and began to tinker with the blisters on his heels. They were huge, suppurating, fascinating things, but they did not seem to slow him down in the least. He was the youngest boy on the trip, and the standard benign abuse of the other scouts naturally came his way. But on the trail he ranged far ahead of everyone else, with a quick, shuffling gait, and seemed perfectly content.

While John was tending his blisters a coed group of Explorer Scouts walked across the far side of the meadow.

“Hey!” John shouted, looking up. “You in the blue shorts! What’s your name?”

The girl in the blue shorts did not answer. She gave a polite little wave.

“They’re real scumbags anyway,” John said, and went back to inspecting the dead skin on his heels.

My memories of Philmont were very sketchy, but the next stretch of that day’s hike was suddenly familiar to me. The walk through Bonita Canyon to Beaubien was not a difficult one, simply endless. I remembered that the camp lay much farther in the distance than we had thought, tucked away in the canyon’s lap. We walked now for three hours, expecting it to come into view at any moment. Most of us by this time had blisters; mine were on the balls of my feet, which I had wallpapered earlier with moleskin. The troop walked on and on through the valley, which kept extending itself ahead of us like an optical illusion. “Why hike?” asks Green Bar Bill. “Because you are an American boy! Because there’s roaming in your blood.”

I walked behind Kuebodeaux. He had a brand-new backpack with a plastic frame that towered high over his head, so that all I could see of the scoutmaster were his short, sturdy legs pumping evenly beneath the rust-colored field of his backpack.

Kuebodeaux works as a dispatcher at the Mobil chemical plant in Beaumont. He is 44. Though he had never been a Boy Scout, he agreed to take over the leadership of Troop 10 after it folded under another leader. It was not difficult to understand why the troop was now a success. Kuebodeaux had a light, almost invisible touch with his scouts, and it was plain he was devoted to the troop. When I visited his house in China, his wife, Dean, was busy ironing his uniform, and she had just finished affixing the iron-on letters to the newest batch of Ragin’ Cajuns T-shirts. Kuebodeaux showed me photograph albums and scrapbooks of past Troop 10 activities, which included a trip to the last jamboree and a variety of fundraising efforts that provided the troop with enough money to buy six canoes and to custom-build a camping trailer. He was proud of the scout hut where they held their meetings, whose every wall was filled with advancement charts, patrol flags, trophies, ribbons, and patches. In the fourteen years Kuebodeaux has been scoutmaster, Troop 10 has produced twenty Eagle Scouts.

“I guess I just stuck with it a little longer,” he said. “When those first four made Eagle the next bunch started coming up and I just couldn’t let them down.

“You just gotta act like those kids, that’s the secret to it. Don’t ever act like an old man. Sometimes you might have to put the belt to ’em, but probably no more than once every three or four years.” “He’s a first-rate scoutmaster,” Scott had told me earlier. “It broke his heart when I didn’t get Eagle.”

It never occurred to me, as a boy, just what my scoutmaster had given up to ride herd over forty boys. I liked him, admired him, and at my parents’ suggestion would give him a little box of handkerchiefs at Christmas, but by and large I just assumed he was some sort of public servant. He was older than Kuebodeaux, with a salt-and-pepper crew cut and a permanent declivity at the corner of his mouth that held the stem of his pipe. He would rouse us out of our cots at summer camp by yelling, “All right, you swabbies, hit the deck!” When I think of him now, I see him standing in the scout hut, in the center of our semicircle of folding chairs. He is in perfect uniform, with his field cap folded over his web belt, and he holds three fingers up in the air, the scout sign that calls for silence.

I was fourteen and had transferred to an Explorer unit by the time I became an Eagle. The award was no big deal to me; I had just stayed in scouting long enough to fulfill all the requirements. But when I ran into my former scoutmaster at some function or other he shook my hand hard and looked me in the eye with a prideful intensity that caught me off guard. Receiving the Eagle to me had meant an orderly marshaling of skills and merit badges; it was like filling up a page in a stamp album. But to him it was a test of character, and I was strangely moved to discover that, at least in his eyes, I had passed.

Beaubien is a working cow camp, presided over by teenage wranglers with names like Snuffy and Cowboy Bob whose job it is to take scouts horseback riding and cook them a “chuckwagon” dinner as a respite from trail food. The elevation here is higher, and I noticed a few aspens beginning to show up as we were led to our campsite by Snuffy, who wore a big black cowboy hat that covered his ears. “If you don’t leave your campsite clean,” he said, “we’ve been known to ride to your next site and make you eat the garbage.”

A hundred scouts showed up for the chuckwagon dinner, which was actually cooked on an open fire next to a stationary chuckwagon. The food was canned stew, along with biscuits and peach cobbler cooked in Dutch ovens. Afterward the leaders and advisers congregated on the front porch of the cowboy cabin, propping their legs up on the rail and looking out at the valley. The leaders talked about politics, weather, beef—man talk. One of them wore a camouflage Aussie hat with the chinstrap set tight below his lower lip like a West Point cadet. He looked maniacal. The others had a gentler, more scoutmasterly appearance. I sat on the porch and listened to them talk, hearing the same male speech rhythms I used to hear as a boy lying in a tent at night covered with 6-12.

The scouts were beginning to wander down to the chuckwagon again for the campfire program. The cowboys had already built a fire, and when it grew dark they got out their jug band instruments and started singing “Rocky Top.”

“It’s time for you guys to exercise your vocal cords,” one of them said when the song was finished. “Now repeat after me. Howwwwwwdeeeeeee!”

The scouts returned the greeting, but the cowboy was not impressed. “I want to see them pine trees shake!”

When the audience responded satisfactorily the band struck up a tune about Beaubien’s resident bear.

He’s big around the middle, he’s broad about the rump.

Runnin’ ninety miles an hour, takin’ forty feet a jump.

They finished that one and were halfway through “Cosmic Cowboy” when there was a disturbance in the audience and scouts began pointing to the chuckwagon. There, barely visible in the dusk, hardly more than a suggestion of itself, was a bear. As if he understood that his presence had been invoked by the song, the bear ambled over to a small rise of ground and simply stood there, on display. The kids went wild. They gave the bear a standing ovation, whistled at him, cheered, delirious with their collective conjuring power.

It was that kind of night. After the campfire ended—with an appropriately spooky rendition of “Riders in the Sky”—the scouts drifted out into the meadow and back to their campsites, listening to the lowing cattle and gazing up at a point of light on the edge of a crescent moon that, I read in the newspaper later, was the planet Jupiter.

Beaubien is a soothing place; it was at Beaubien that my old Philmont troop had finally begun to work together instead of apart. Now, as soon as they got back to camp, most of the scouts headed for their tents. I lingered out in the open for a while, wondering what kind of trees we were camped in tonight. The cowboys at the campfire kept talking about pines, but these didn’t look like pines to me. I gathered a few needles and dug out my handbook to see what Green Bar Bill had to say. The needles were four-sided, squatter and thicker than pine needles. According to the handbook, they could only be spruce.

You just can’t go wrong with the Boy Scout handbook. Surely it is one of the most eclectic volumes in print—a field guide to birds, mammals, reptiles, animal tracks and habitats; a how-to book about knot tying, first aid, family life, axmanship, nutrition, religion, scout advancement. It tells how to stalk a deer and how to insulate a house, how to treat snake bite and how to clip your nails. It tells you what to say when you answer the phone (“Bill Jones here”), as well as how many times to let the phone ring before hanging up (ten).

How to read scat, how to speak in Indian sign language, how to clean your ears—it’s all there.

There have been almost a dozen editions of the handbook since Baden-Powell’s Scouting for Boys, but the current one, published just last year, is the best ever. Most of the books were written by committees, but the new edition is the product of one voice. Green Bar Bill’s prose style is warm and even, scaled without artifice or condescension to the reading mind of a twelve-year-old boy. Reading it straight through, one comes away with a strong impression of sincerity and kindness.

“Good manners always please and attract people,” Green Bar Bill writes. “Open a door for a lady. Offer a seat in a bus to an elderly person. Rise from your chair when a guest enters the room. Help your mother be seated at the family table. Say ‘Pardon me’ or ‘Sorry’ when needed. These are manly things to do.”

“You are the guests of the birds and animals,” he reminds us. “Help them. Don’t hurt them.” He tells scouts to “fight for your convictions,” that “you never need to be ashamed of the dirt that will wash off,” that “it is not the good times you have that will make you the man you want to be. It is only as you learn to overcome difficulties with a smile that you will grow to be a real man.”

Green Bar Bill is now eighty years old. I went to see him in Manlius, New York, where he lives in a little apartment in the back of an old friend’s house. There was a totem pole in his yard—made by Dan Beard, founder of the Sons of Daniel Boone—and a big scout badge attached to the outside wall of his patio. Mr. Hillcourt—as I addressed him, not thinking it appropriate to call him Green Bar Bill to his face—came to the door wearing a polo shirt and double-knit shorts. He had a clean-lined, inquisitive face and spoke with a Danish accent.

He seemed puzzled that I should have come all the way to New York just to see him, but as soon as I entered his study I knew I had found what I wanted. Green Bar Bill made believable the improbable link between a histrionic officer in the Boer War and a group of Cajun boys in China who put on uniforms and swore oaths.

The study could not have looked any other way—it was as predictable an environment for Green Bar Bill as a woodchuck den would be for a woodchuck. It was filled with scouting paraphernalia: books, Order of the Arrow patches, a signed Norman Rockwell print, souvenir coffee cups from jamborees and adventure bases, plaques, statues, a photograph of the young Hillcourt with Baden-Powell. It was clear to me that Hillcourt existed very near to the heart of the scouting movement, and that his study was as much of a national headquarters for the Boy Scouts as the offices they maintained within limousine distance of the DFW airport.

I asked Hillcourt about a needlepoint map of Denmark that was hanging on the wall. “Denmark is shaped like a big man wearing a cap,” he said. “Here are his eyes and here is a great big nose, which is dripping, and which explains these peninsulas here.”

Hillcourt was born on one of the peninsulas—near the city of Aarhus—in 1900. He first became a Boy Scout shortly after the publication of Scouting for Boys in 1910. “My brother happened to be in a bookstore when the book arrived. He bought one and brought it home. It said if you wanted to be a Boy Scout all you had to do was get together with a group of boys and form a patrol. And that’s exactly what I did in January of 1911.

“I first saw Baden-Powell in 1920 at the first world jamboree when he was proclaimed Chief Scout of the World. Every Danish troop had a chance to send one representative and my troop sent me. I picked up a disease there called jamboritis. There’s no cure for it, but you can get some relief if you keep going to jamborees.”

Hillcourt came to America and joined the national staff of the Boy Scouts of America in 1926. During his time with the organization he wrote the 1944 Scout Field Book and his other classics of scouting literature. He retired in 1965 but soon became alarmed at what he saw as the “downhill” drift of the movement.

“We had three handbooks and the word ‘campfire’ didn’t appear in the index of any of them. Instead of being a book about having fun in the outdoors, it was all about advancement and skill awards, starting with the ones that are least interesting to boys—Citizenship, Family Living, that kind of thing. Then on page 195 you finally get Hiking. Suddenly the Camping merit badge wasn’t required for Eagle. The old-time scoutmasters didn’t understand what was happening.”

To remedy the situation, Hillcourt said, he offered the Boy Scouts “a year of my life, free of charge, to write a new handbook.” They took him up on it, and the handbook was published last year. To date it has sold a quarter of a million copies, on which Hillcourt receives no royalties.

Hillcourt showed me his collection of books by Baden-Powell, including the original installment edition of Scouting for Boys and the volume about pigsticking. “To this day you can go to the library and ask for the standard work on pigsticking and this is the one they’ll hand you,” he said.

Hillcourt also had Baden-Powell’s scout knife, which he kept in a Ziploc bag. And he had a lot of mementos of his own scouting career: a Silver Wolf, a Silver Hawk, a Silver Beaver, and a Silver Buffalo, as well as a Distinguished Eagle Scout award. I asked to see his uniform, sure that it would be full of all sorts of showy and arcane council patches and Order of the Arrow flaps. He took it out of his closet and laid it on the bed. It was totally unadorned except for one small, discreet patch on the left sleeve that said “Green Bar Bill.”

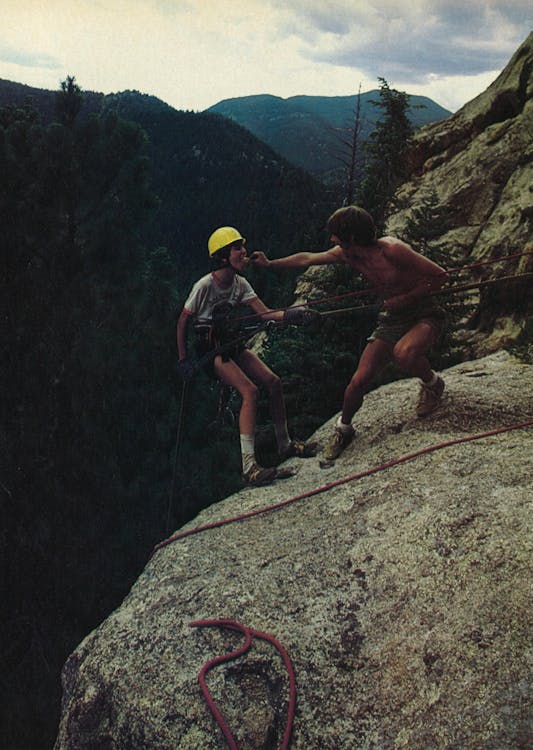

The troop walked six or seven miles to another camp called Miner’s Park, which featured a rock-climbing program that took place on twin mounds of granite named Betty’s Bra. “What we’re going to do here is teach you a little about rock climbing,” one of the staff members said, looking down at the scouts from a high ledge. “Probably just about enough to get you killed if you went out and tried it on your own. Now, if somebody yells, ‘Rock!’ while you’re climbing up here, don’t look up because it’ll hit you in the face. If you hear somebody yell, ‘Boulder!’ go ahead and look up, because it’s going to cream you anyway.”

The scouts put on their helmets and harnesses and climbed up the rock face while the staff belayed them from above. There were two routes from which to choose, and the older boys took the harder one as a matter of pride. When they came down from the Bra some of the scouts cleaned up in a wood-stoked shower while the rest went about the business of preparing dinner. The big cooking pot took a long time to boil water, and the scouts sat around the fire gazing at it hungrily, holding the Frisbees they used as plates.

“I’m so hungry I could just about eat that stuff raw,” someone said.

“I once ate four worms for twenty dollars,” David Mitchell said.

“Come on.”

“I did. I swear.”

“No wonder you’ve got gas,” said Andy Kuebodeaux.

“I ate a frog for fifty dollars and a crawdad for thirty-five dollars.”

“Would you eat dirt?” Andy asked. “How ’bout an old dried-out cow chip?”

“Let me think about that.”

“How about some Tetrox?”

“How much’ll you pay me?”

David could see that they were not taking him seriously, so he prowled around in the grass awhile until he found a grasshopper. He said he would eat the grasshopper for $5. No one took him up on it.

“Okay, I’ll eat it anyway,” he said. And he did.

“Woooeeee!” Cotton Waldron said. “That next fart’s gonna bounce!”

Kuebodeaux watched all this indulgently. He intended to get the boys to sleep early tonight, because the next day was a killer: an eleven-mile hike that would take them up and down two 10,000-foot peaks. I was planning on leaving them in the morning, and I was glad now I had picked that day to do so.

After dinner the camp staff invited the leaders over to the cabin for coffee and bug juice. You could tell that the staff had been in the backcountry for a long time, because one of them still had a pet rock, which he dragged around on a leash tied to his belt.

That night I slept with the staff on the roof of their cabin, which had a pronounced downward slope that made me afraid I would simply roll off the roof in my sleep. No one else seemed to worry. They traded a little backcountry gossip and then went to sleep. I lay awake for a long time, looking up at the summer star field, trying to piece together a few remnants of knowledge about the constellations from my study for the Astronomy merit badge. A wind came up, gusting from the north, and in the southwest there was heat lightning: silent, regular pulses of white light that came out of a clear sky. What caused that? Green Bar Bill would know, just as he could point out Perseus or Auriga in the swarm of stars above me.

I wrapped my boots in my jacket and used them for a pillow. The camp was quiet. Troop 10 was bedded down; I could see the outline of their tents below in the flash of the heat lightning. Kuebodeaux had his alarm set for four-thirty so he and the boys could make a few miles before having to stop for breakfast. I was more than ready to go back to base camp; maybe I would reach it in time to join all those knobby-kneed scouters down there for a high-starch lunch in the mess hall. But a part of me—specifically, that part of me that was not my feet—wanted to press on with Troop 10, to climb with a full pack all the way to the summit of Black Mountain, and to sit there eating a cold lunch of turkey spread and crackers, exhausted but primed to go on.

“Yes, it’s fun to be a Boy Scout,” writes Green Bar Bill. “It’s fun to go hiking and camping with your best friends… to follow the footsteps of the pioneers who led the way through the wilderness… to stare into the glowing embers of a campfire and dream of the wonders of the life that is in store for you.”

Kuebodeaux’s alarm went off forty-five minutes late, but by the time I had jumped down from the roof at six o’clock the scouts were already performing the ritual of drowning their campfire. The tents were struck, the packs were loaded and lined up in the center of the camp, and everyone in the troop was decked out in a clean Ragin’ Cajun T-shirt. They did me the farewell courtesy of three and a half Hows (How! How! How! Huh!) and said they sure wished I could go with them. Then they moved out in an orderly single file, some of them hobbling along on their blistered feet but uncomplaining—“A Scout Is Cheerful”—up the steep trail that led past Betty’s Bra and over the next mountain.

- More About:

- Longreads