This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The Sukeba II left Port O’Connor around five Friday morning, finding its way out through the dark channel with the help of radar and buoy lights. At first the other tournament-fishing boats kept pace, but the Sukeba II is fast, making around 25 knots at top speed, and it soon drew out of sight of the competition. But it wasn’t out of hearing: the radio chattered incessantly as the fishermen called one another to make last-minute bets.

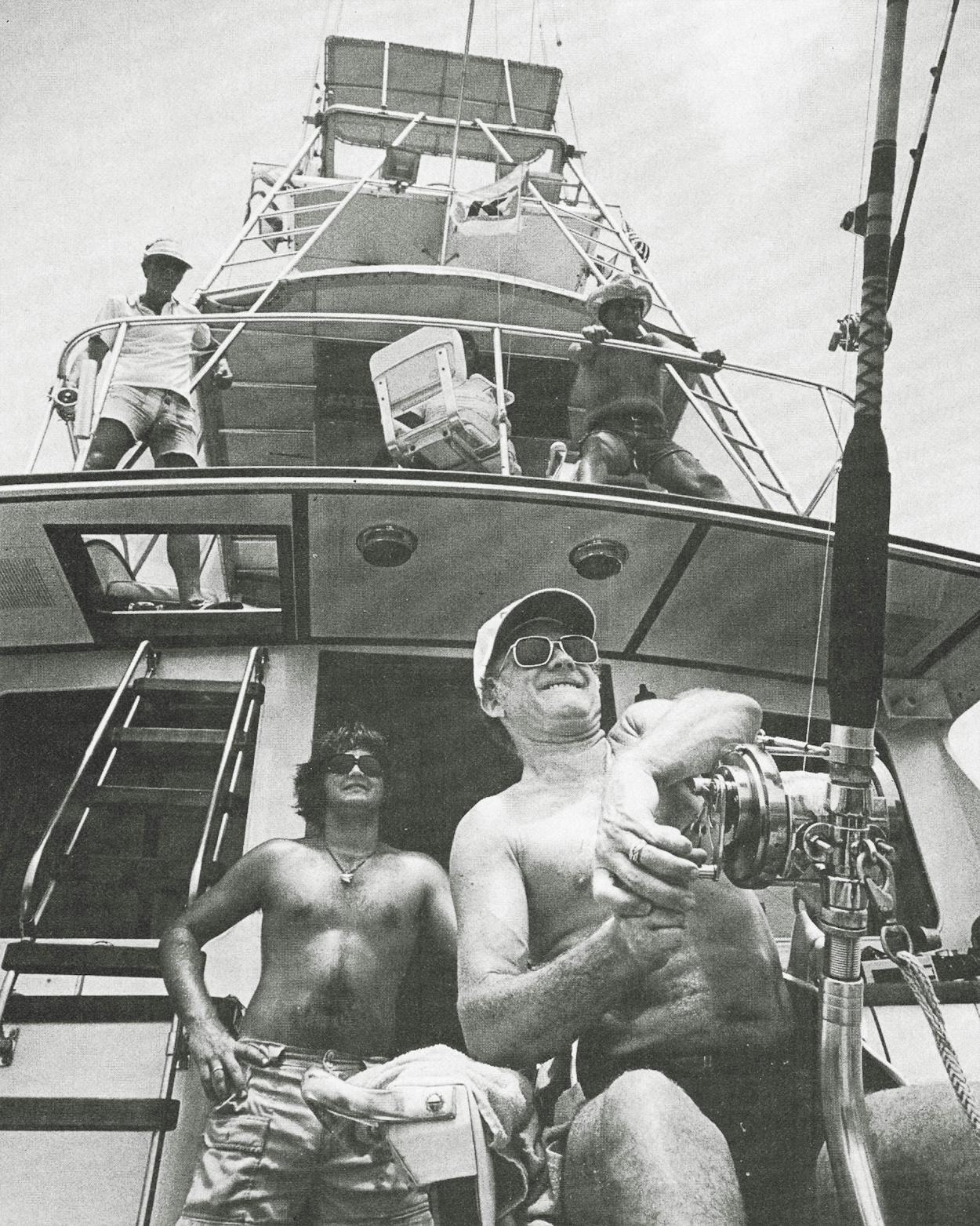

A 65-foot custom-designed fishing boat, the Sukeba II is owned by millionaire oil consultant Henry Keplinger of Houston, who doesn’t like his first name and prefers to be addressed by his nickname, Kep. Keplinger had come for the Poco Bueno Port O’Connor Offshore Association billfishing tournament, more commonly called the Walter Fondren tournament, after its founder, a former running back for the University of Texas and now a Houston investor. Fondren and a few fishing buddies had fished competitively against each other in a haphazard way for years. But they wanted to find out who the best fishermen truly were, so in 1968, over a bottle of Scotch, the tournament was born.

Ninety boats entered in 1980; most of them had survived a waiting list of several years, for this is the Gulf Coast billfishing tournament, and every sportsman willing to invest $500,000 to $1 million in a boat and crew wants to enter. They don’t come just for the money, though this year it amounted to nearly half a million dollars. The true allure is that big-time billfishing may be the most exclusive sport in the world. As one of the boat owners pointed out: “Hell, nowadays anybody can belong to the country club and own a set of golf clubs. A lot of guys can afford African safaris or even a stable of polo ponies. But not many can come up with the dough to buy and maintain a true blue-water fishing boat like you’ll see down here.”

As the sun came up, the water began to change color. When the boats had left the Port O’Connor docks the bay had been gray; about ten miles out, the water turned green and then turquoise and then a startling cobalt blue. The Sukeba II was headed past the continental shelf, where the floor of the sea suddenly plunges from a depth of thirty or forty fathoms (180 to 240 feet) to eighty or a hundred fathoms. It is at the continental shelf that the big marlins and sailfish live. Kep’s boat got there about eight-thirty, when the sun was already beating down.

Kep had won the tournament in 1978 and was intent on winning it again. So his crew had avoided the onshore activities: a dinner party every evening in a central circus-style tent, parties in private homes, parties on board the various boats. As at all rich men’s tournaments, there were plenty of distractions. A party atmosphere prevailed, created by wives, friends, and hangers-on who weren’t there for the serious business of fishing but just to have a good time. Since midweek the tiny Port O’Connor airport had been crowded with private planes flying in the crowd.

The festivity peaked Thursday afternoon in an exercise called the Intercoastal Canal Olympics. This consisted of the Rope Walk, the Chair Throw, and the Ridden-Out-of-Town-on-a-Rail Race. The last event was probably the most painful, but the most demanding was easily the Rope Walk, which required each contestant to traverse a hawser stretched forty feet across one of the boat slips. As if walking the swaying rope with the anticipation of falling in the water wasn’t difficult enough, the competitors had to drink three beers each before trying it. Fondren had set the meet record the year before by making it halfway across, but he’d retired on his laurels, claiming that the glory wasn’t worth the rope burns he sustained when he fell.

But while others might have come for entertainment, Kep had come to fish. A surprisingly quiet, self-effacing man, considering his wealth and position, Kep has been chasing the wily billfish for a good ten years, during which he has owned a succession of boats, each one bigger and more elaborate than the last. If you ask him to define the fascination of game fishing he will grin and say, “Hell, I don’t smoke and I don’t drink. Everyone’s got to have a vice; this is mine.” Then he adds seriously, “I work very hard, most times fourteen to sixteen hours a day, and this is just about the only form of relaxation have.”

On board the Sukeba II as guests and to do a little business on the side were George Temple, a Houston oilman; Richard Adkerson, a high-powered accountant from Houston; and Tom McGreevy, a financier from Santa Fe. All had flown in on Kep’s turboprop MU-2 plane. Captain Gerald Needham and his two mates, Joey Woodhead and George Overton, made up the crew. The captain and Joey are full-time crewmen; George Overton is something of an anomaly, a man of means himself but not wealthy enough either to own such a boat or prominent enough to be asked to fish on one. He had been invited simply because he was one of the most knowledgeable billfishermen on the Gulf Coast.

Under the rules, Kep could not begin fishing until nine, but the remaining time was well spent in cruising slowly while the captain looked for patches of floating seaweed or slick water or schools of bait fish—anything that might attract the billfish. There are three above-deck levels on the Sukeba II—the main deck, the flying bridge where the captain steers the boat, and finally, some twenty feet above the deck, the tuna tower. From the tower one can sometimes see a big billfish swimming along just below the surface. George Overton stood there, scanning the sea for any clue to where the fish were.

The craft entered in the tournament ranged in size from 45-foot Bertrams and Hatterases up to custom-built boats like Kep’s 65-footer, the largest boat in the tournament fleet. Though these boats are intended primarily for sportfishing, they are luxurious indeed. Most can sleep eight or nine people and have air-conditioned salons, several bathrooms complete with showers, and elaborate galleys that are bigger and better appointed than the kitchen of the average apartment. Most are equipped with sonar, depth finders, bottom scanners, and the best radios available. Some even have loran (long-range navigation), a necessity for boats that sail into foreign waters for the fishing near Cuba and the Bahamas and even off the coasts of Central and South America. The Sukeba II houses two private staterooms and three bathrooms. There is even a color television set aboard. In fact, sitting in the air-conditioned salon drinking beer or iced tea, the crew could have easily forgotten what they had come for—to haul in the biggest and the most billfish.

Kep wasn’t about to let them forget, though, and at nine they tossed out the baits. A boat the size of the Sukeba II trails five baits, two from outriggers, two from rods set along the side rails of the fighting cockpit, and one from a rod right in front of the fighting chair. Kep was using artificial baits, which can be skipped faster than dead bait, allowing him to troll faster and cover more water.

Patience is a necessary virtue in billfishing, which is one reason that the boats are as comfortable as possible. But after only an hour of trolling everyone jumped into action as one of the lines abruptly snapped out of the clips that held it to the outrigger—a knockdown, as it is called. The excitement soon abated, though, when George Overton reported that a lowly twenty-pound wahoo had taken the bait. Wahoos are good to eat, but they have no value in a billfishing tournament, so George Temple landed the fish. Kep was the most experienced angler on board, and he would fight the first billfish that took the bait. The three guests did take thirty-minute turns in the fighting chair, for luck and their entertainment. They kidded each other about who would be in the hot seat when a big blue marlin got on a line and how they would keep Kep from taking the rod by locking him in one of the bedrooms.

The winning catch is based on a point system. In addition to the points given for weight (one per pound), a blue marlin is worth five hundred points, a white marlin three hundred points, and a sailfish one hundred points. Obviously, the biggest prize is the blue. It is the largest, the scarcest, and the hardest to catch of all the billfish. Some blues weigh up to one thousand pounds, but these are rare and are found only in the waters off Australia. Most of the blues in Gulf Coast waters average three to four hundred pounds. They are a true fighting fish, sometimes leaping spectacularly out of the water as they thrash about trying to throw the hook, sometimes going to the bottom and refusing to surface for hours, sometimes even ramming the boat. Depending on the skill of the captain, the strength of the angler, and the fight in the fish, landing a blue can be an all-day ordeal. Two weeks after this tournament the Chingadera, one of the most impressive boats, caught a 672-pound blue during a tournament at Port Isabel. It required a six-hour fight to boat the fish, and Rob Terry, the angler, couldn’t unclench his hands for twenty hours after the fight.

White marlin, although more abundant than the blue, run only about half as big. A very large one might weigh three hundred pounds. And sails, the most common of the billfish and therefore the least prized, average only about sixty pounds. But regardless of their size, all billfish are elusive. One expert has estimated that it takes 55 hours of trolling to catch one fish, which meant that the tournament entrants faced pretty long odds: they would be fishing on the waters of the Gulf for a total of only twelve hours over the two days of the contest.

As the morning wore on, Gerald Needham worked the boat back and forth over the blue sea, searching for any sign of the big fish. At one point George Overton sang out from the tuna tower that a marlin was rising for the starboard bait. The knockdown came and the line went whizzing out, making the screaming sound of huge deep-sea fishing reels. But it was just another wahoo. George came down from the tower cussing. “I swear,” he said, “I saw a good marlin. That damn wahoo jumped on that bait before the marlin could hit it.”

Before long, radio reports on what the others were catching started to come in. By late morning any number of boats had one sailfish on board, and the Little Sister and the Teal had each landed a white marlin. By noon the Aquarius had two sails and the little Bil-Fisher and the Charybdis had each caught a white. Kep was falling significantly behind. He had reckoned that of the ninety boats entered, his chief competition would be Bill Brock, Bob Byrd, and Rob Terry, joint owners of the Chingadera, and Walter Fondren, whose boat was the Tsunami. He based this judgment on their past performance, the quality of their boats, the skill of their crews, and the price they’d brought in the Calcutta.

A Calcutta is a betting pool. Each boat’s chances of winning had been sold to the highest bidder and then the money was pooled. Once the tournament was over, the owners of the top eight boats would receive half the money, and the bettors on those boats would be paid the other half. (Another $45,000 in prize money came from the entry fees.) The bidding had been held on the Wednesday night before the tournament was to begin. In the big tent that had been set up close to dockside two professional auctioneers hawked the boats. Most went for $3000 to $4000 until the Chingadera sold for $7500. The Tsunami brought the highest price, $10,000. Kep’s boat was second at $9000. Both Walter Fondren and Kep formed syndicates with their guests and crew members and bought their boats’ own chances. A betting syndicate headed by Russell Stein, a Houston stockbroker, bought the Chingadera’s.

Kep had turned in for the night before they got around to bidding on the Sukeba II. But he left a blank check with his captain, Gerald Needham. A near-disaster occurred when the auctioneer didn’t hear a bid from Needham and almost sold the boat to another bidder for $8000. The mistake finally got straightened out, though, and Needham’s bid was recognized. “Hell,” he laughed, “Kep would have fired me if I hadn’t’ve got that bid in.”

One o’clock came and went, and still the sea around the Sukeba II remained empty of tournament fish. More reports came in: by two o’clock ten sails and seven whites had been caught. The boats were now entering the dead part of the day, when the fishing would be at its poorest. “Damn,” Captain Needham fretted, “I’d give a pretty penny for just one blue. Even a little one. We’d wipe out everything every other boat has got so far.”

Then, at 2:20, the port inboard rod suddenly began to sing. “Knockdown!” yelled George Overton from the tuna tower. George Temple had been sitting in the fighting chair, but he quickly got out of the way as Kep came scrambling out on deck from the salon. “It’s a blue,” Overton reported. “I can see him.”

On the flying bridge, Needham began backing the boat to make it easier for Kep to take the rod out of the railing socket and get back to the chair with it. They’d attached a safety line to the big rig, so it could be recovered if it got jerked out of his hands. Kep is not a very big person to start with, and he’d recently had an operation on his right elbow. It was all he could manage, even with the boat backing down and the line singing out, to hold the heavy rod and get to the chair. “We’re losing too goddam much line!” he yelled at Needham. “Goddam, Gerald, give me some help with this boat!”

“You’re all right,” Overton said as he came tumbling down the ladder from the tower. He and Joey immediately began to rig the fighting harness around Kep’s torso. “You got him now, baby,” George said. “Just stay with him.”

Now began the careful business of keeping the fish on the line as it wore itself down. Although most of this maneuvering was done with the boat, Kep decided to try to get some line back. Over four hundred yards of the 130-pound test line had already gone out, creating a terrific drag. So, in slow surges, Needham backed down on the fish while Kep tried to reel in. It was difficult, for the blue was swimming in a zigzag pattern. George Overton stood behind Kep’s chair, swinging it back and forth to keep the line pointed where he thought the fish would be. “He doesn’t know he’s hooked yet, Kep,” he said. “You better put some strain on him.”

Kep was looking tense, as was everyone else. “How big you think he is, George?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” George said, “but I bet he’ll go two hundred easy.”

Then Kep noticed the crowd around him. “Some of you guys get up top,” he commanded. “We don’t need this many people down here. And watch those cigarettes, goddammit. One spark and this line is gone.”

All of a sudden the big fish seemed to realize it was hooked. Down it went, heading for the bottom. From the flying bridge Needham yelled, “He’s sounding!” The captain immediately started to back the boat down. The rod abruptly bent and the line began to scream out. Kep, who had been straining with both hands to hold on, suddenly jerked one hand loose to jam the big drag lever on the side of the reel to full drag. The line slowed, but not much.

“Gerald, dammit, we’re going to lose this fish!” Kep yelled.

“You’re all right,” the captain called back.

Joey got some liquid detergent and squirted it on the seat of the fighting chair to allow Kep to slide back and forth more easily as he fought the fish with his shoulders and upper body, trying to retrieve some line. Now the fish was not moving, just lying immobile on the bottom. “He’s down there sulking,” Overton said.

The action settled into a pattern: Kep pumping the fish, trying to bring him up, trying to gain back a little line; Needham cautiously helping him by maneuvering the boat. Then an unexpected danger appeared. A seismograph boat was bearing down on the Sukeba II from the port side. Behind it, on a mile of cable, the boat was pulling a barge that dangled wires and equipment almost to the bottom. If the boat crossed Kep’s line it would be snapped and the fish lost for sure. Everyone began to yell at once. Needham, trying to see the name of the boat, frantically called for the binoculars. Meanwhile, Kep was shouting for someone to do something. He couldn’t turn and see the seismograph boat, but he knew what it meant.

“You just fight this fish,” George said as he swung the chair toward the fish’s position. “Get him off the bottom.”

At what seemed to be the last minute Needham reached the captain of the seismograph boat on the radio and it sheered off, taking a course that would clear Kep’s line—if the fish didn’t decide to run in that direction.

Kep had been fighting the blue in the broiling sun for 45 minutes now, and the strain was beginning to tell. The crew put a towel over his shoulders and soaked it with ice water. He was still trying to move the fish, struggling to get in a few turns of line on the big reel. Then, suddenly, the reeling was much easier. Someone groaned, “We’ve lost him.”

But George said, “No. He’s coming up. Reel like hell, Kep. Don’t let him get too far ahead of you.”

Kep was shouting for Gerald to give him some help with the boat. But the boat was doing fine, edging forward at just about the right speed as the fish rushed toward the surface and Kep reeled frantically. Then the blue jumped, rising out of the water and turning in an arc to plunge straight back into the sea. He was about two hundred yards off the stern and he was big. “Better than two hundred pounds,” George said. “Maybe two-fifty.”

It was now past three o’clock and no one else had reported a blue. If Kep could boat this fish he’d be leading the tournament. As the fight went on the marlin was clearly beginning to tire. Gerald and George wanted Kep to work the fish harder, to get it in the boat as fast as possible. Kep did begin reeling harder, but he did it reluctantly, complaining that the fish still had too much fight in it to bring it in.

Then somebody yelled, “There’s the double line!” The double line is two strands that connect the leader to a swivel secured to the main line. It was now just breaking water, meaning that the marlin was no more than forty feet from the boat.

George said, “Look at that swivel—it’s cocked.” Worried that it might snap, Kep backed off, giving the fish a little slack to take the strain off the swivel. Needham had jumped down into the fighting cockpit, where there is another set of controls, and was running the boat from there. The crew held a hurried conference about what to do, whether to bring the marlin in quickly, risking the extra stress on the metal, or to work it slowly and take a chance that the swivel might chafe the line in two. Kep wanted to play it conservatively, but Gerald and George thought it best to boat the fish right away.

“It’s six of one, half a dozen of the other,” they argued. “Let’s try him.”

Reluctantly Kep began to crank on the big reel. The fish came closer as the double line again broke water. Now they could see the marlin clearly in the water, swimming slowly behind the boat, its bill slicing the water, its dorsal fin raised. It looked big, very big.

The cockpit was cleared of everyone except the crew. Gerald grabbed the flying gaff, which works like a harpoon: the gaffer can hit the fish, leaving the gaff head embedded, and then pull it in with an attached rope. Slowly Kep worked the big fish up to the back of the boat. Joey opened the transom door, through which the fish would be pulled once it was close enough. George had gone to the controls and was keeping a slow speed ahead. Suddenly Gerald leaned over and struck the marlin behind the gills. The crew hauled it aboard, and Kep had his fish. It lay there long and blue, iridescent, about ten feet from its tail to the tip of its bill.

“He’s a good one,” George said.

Everyone on board made the trip home in a state of quiet excitement. Once Gerald had reported the fish, the radio began to crackle with congratulations from the other boats. Kep, sitting back in the lounge with a diet drink in his hand, commented, “Catching a good one sure makes the trip back a lot shorter.”

A large crowd was gathered around the weighing dock when the Sukeba II pulled in, and they cheered as the fish was unloaded. It weighed 262 pounds, which, with the 500 points for catching a blue, gave Kep 762 points and a commanding lead. Neither the Tsunami nor the Chingadera had caught anything; the smaller boats, none of which had been considered a threat, had had all the luck.

There was a dinner and a party that night, but it was not well attended—most of the crew members were now concentrating on the fishing. Kep’s men were asked a lot of questions about where they’d fished. Gerald said he figured the Sukeba II would have more company the next day but that it didn’t make any difference if others tagged along or not; one boat might get several fish, while a quarter of a mile away another boat would never get a strike.

The next morning, going out again through the dark channel, the crew was filled with anticipation. But the first indication that things might not go so well came only twenty minutes after the lines went out, when the Mary Jane, a 46-footer, reported she had hooked a blue. Then the Spare Time said that she was tied on to a blue. Still, Kep wasn’t worried; he had all day to fish and he didn’t need much besides a couple of sails or a good white to win. If he got another blue he was a sure winner.

Soon the Mary Jane called in that she’d boated the blue and that it would weigh at least two hundred pounds. The Spare Time reported that her blue was “just average.” So Kep felt he was still leading—until he heard that the Mary Jane had boated a sail. Sounding a little worried, Kep said, “We better put something on board. We might not be ahead anymore.”

Other boats were calling in steadily with reports of sails and whites, too fast to keep an accurate record of who had what. A boat whose name Gerald didn’t catch reported she was tied on to a blue, but nothing more was heard, so Kep assumed she’d lost it.

Meanwhile, the Sukeba II’s sea yielded nothing. Gerald patiently trolled back and forth over the continental shelf, looking for grass, looking for slicks. Up in the tower George scouted for fish. Once he spotted a school of yellowfin tuna, but Gerald steered carefully around them because Kep couldn’t afford the time it would take to reel one in. A little after noon the Mary Jane reported she had another sailfish on board. “This is getting serious,” Kep said.

By now the guests were doing everything they could think of to change Kep’s luck: switching brands of beer, changing shirts, varying the order of the visitors to the fighting chair, calling on all the known fishing gods. But none of it was doing any good.

And then, just before two o’clock, the Katie Ann reported she had a good blue on board. That would go with the sail she’d caught the day before. George said, “I hope we can hold third.”

Gerald replied, a little grimly, “If we are third.” At two-thirty he blew the boat horn, sounding it four times, not for any particular reason but “just in case,” he said, “the fish hadn’t noticed we’re here.” Then everyone fell silent as the last thirty minutes—and Kep’s chances of winning—slipped inexorably away.

At three o’clock Joey began reeling in the baits and storing the rods and reels in the forward compartment. After that there was nothing much to do except sit in the salon and drink beer or soft drinks.

George Temple said, “Damn, if we’d just caught at least one sail today.”

But Kep just shrugged wryly and said, “That’s fishing.”

As the Sukeba II came idling up the channel in the growing dusk it passed the weighing dock. The same expectant crowd was there, the same jubilant crews unloading their catches. But this time Kep didn’t stop—he had no prize to declare.

They announced the winners and handed out the money that night. The Mary Jane, with 1134 points, was first, winning $150,480. The Katie Ann barely beat Kep out, winning $75,240 for her 769 points. The Sukeba II was third with 762 points. Kep won $56,430. The Chingadera and the Tsunami finished out of the money.

Later, someone remarked that the cash ought to make him feel better about not winning. “Well, I suppose so,” he said slowly, realizing that the speaker knew nothing of the mathematics of owning a craft like the Sukeba II. “I suppose if I’m very careful my share of that check will run the boat for thirty days.” Then he smiled. “But if you go deep-sea fishing after prize money you shouldn’t go at all. There aren’t many sure things in this world, and billfishing definitely isn’t one of them.”

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Fishing