On Tuesday, September 24, about 1:45 pm, Arthur H. Dilly was admitted to the home of Stephen H. Spurr at 2101 Meadowbrook in Austin. Both men knew it was no ordinary visit. Dilly, executive assistant to University of Texas Chancellor Charles A. LeMaistre, had telephoned Dr. Robert D. Mettlen, assistant to UT-Austin President Spurr, a short time earlier with an ominous message.

The message: LeMaistre had a letter he wanted delivered immediately to Spurr. Mettlen, who anticipated what the letter would say, told Dilly to send it out to him and he would deliver it to Spurr at his home. “That probably would not be appropriate,” said Dilly. “It probably should be delivered directly to the president.”

“Good. Come on out,” said Mettlen. Spurr accepted the letter from Dilly at 1:47 pm, saying “Thanks, Art.” The chancellor’s representative left immediately.

LeMaistre’s letter contained two terse paragraphs. The first that Spurr had been relieved of his administrative responsibilities as president of The University of Texas at Austin, effective immediately. The second advised him that LeMaistre’s action in no way altered Spurr’s academic status as a tenured professor in the Department of Botany and at the LBJ School of Public Affairs.

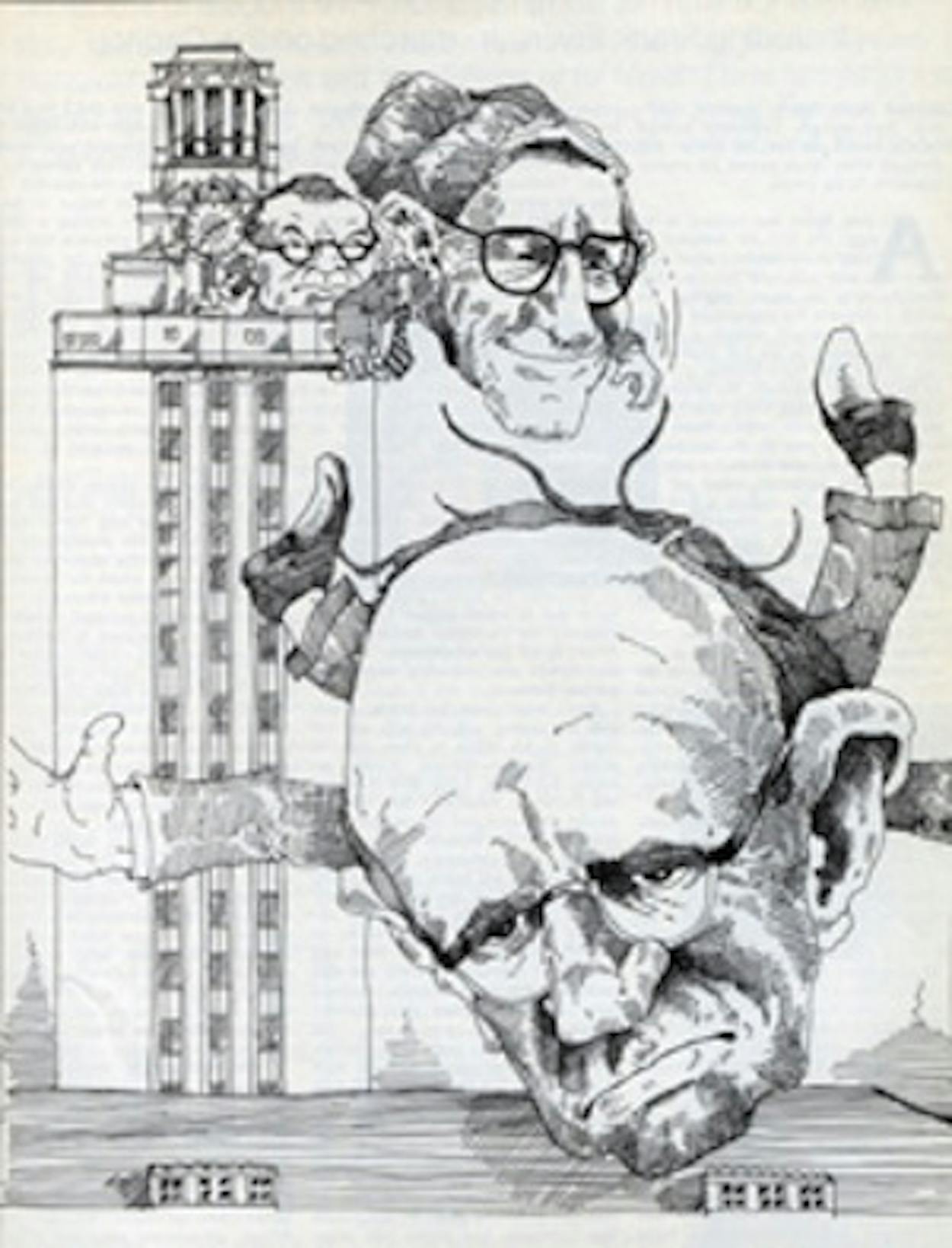

Spurr’s summary dismissal became an instant cause célebre in Texas educational and political circles, and was front-page news for the state’s major dailies. The firing even set off minor shock waves throughout the national academic community, plunging the University of Texas into its deepest crisis in 30 years—since the last time UT’s top administrative official was abruptly terminated. The victim in 1944 was Homer Rainey, fired by the Board of Regents for challenging regental interference with his administration. Five thousand students, including an outspoken young man named Frank Erwin, Jr., had marched on the Capitol protesting Rainey’s firing. The American Association of University Professors reacted by placing UT on its blacklist and formally censured the school; many top instructors left and others never came. The university didn’t really recover academically until the late 1950s and it was not long afterwards that Governor John Connally named an older, wiser Frank Erwin to the Board of Regents.

Erwin, by then was National Democratic Committeeman from Texas, a powerful political figure in his own right, and soon became embroiled in a series of controversies with administrators, faculty, and students. LeMaistre took over as chancellor in 1970; and the exodus began soon thereafter. UT-Austin President Norman Hackerman, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences John Silber, and perhaps a dozen lesser luminaries of the UT-Austin administration, and faculty departed because of differences with LeMaistre and Erwin over how the university should be run—and by whom. Silber was fired; the rest resigned, some on their own initiative, others by request. Spurr’s dismissal culminated a four-year period during which UT lost some of its finest academic minds, but the university never fell into academic disrepute comparable to the post-Rainey period. What effect Spurr’s firing will have, however, remains to be seen.

The firing came 36 hours after LeMaistre (with deputy chancellor E. D. “Don” Walker on hand as a witness) confronted Spurr with a demand that he sign a suggested letter of resignation or face dismissal that very day. It was a tactic that LeMaistre had used from the very outset of his administration. Spurr was stunned by LeMaistre’s rapid recital of allegations and by the demand for his immediate resignation. He was not given the opportunity to respond to the charges—LeMaistre had already made up his mind—and the chancellor’s sole concession was to give Spurr time to discuss the terms of his resignation.

Spurr had underestimated both the growing discontent of several regents with his administration and LeMaistre’s increasing determination that he had to go. Spurr had long suspected that Erwin wanted him out, and he knew that he had irritated regents Ed Clark of Austin and Jenkins Garrett of Fort Worth. If Spurr needed further evidence that he was on shaky ground, he needed only to recall an incident that took place during the summer. An Austin regent, probably former Texas governor Allan Shivers, warned Spurr that LeMaistre would ask the UT-Austin president for a medical certificate to determine whether Spurr had sufficiently recovered from open-heart surgery to perform his duties. This seemed odd to Spurr, because LeMaistre is a medical doctor who was completely informed about Spurr’s medical condition. Sure enough, LeMaistre insisted on the certificate, but the matter was dropped when Spurr passed the evaluation with flying colors.

At first, Spurr was inclined to resign. He says he intended to step down anyway after January 10, 1975—the date Erwin’s term as regent expires. He asked LeMaistre for contractual assurance that he would receive a year’s leave of absence at his full professor’s pay of $38,000, three-fourths of what he received as president. He requested approval to continue living rent-free in the president’s home, with utilities and household help paid by the university, for one year. He also wanted continued free use of a university-leased car for a year. Finally, he desired a $10,000 annual research grant, renewable on a year-to-year basis, to hire a research assistant and meet nonsalaried research expenses. The financial difference between resigning and being fired totaled more than $50,000.

LeMaistre, a cold, humorless man whose distrust of academicians as administrators has been manifest from the first days of his chancellorship, agreed to go along with Spurr’s terms, subject to regent approval. Others who involuntarily resigned from administrative positions to devote full time to teaching and research had received similar benefits.

Despite these initial negotiations, Spurr had reservations about resigning. He asked LeMaistre whether the chancellor had issued the resign-or-be-fired ultimatum at the request or with the approval of the Board of Regents. “He told me that he had the unanimous backing of the board to take whatever administrative action he wished in the matter,” Spurr said shortly after his dismissal. Later, when asked by philosophy Professor Edmund L. Pincoffs, chairman of the select faculty committee investigating the firing, to specify exactly what LeMaistre had said about the support of individual regents, Spurr backed off slightly: “I cannot recall the-exact language used by the chancellor, but I do know that I was led to believe that the chancellor was acting on behalf of the Board of Regents,” Spurr said, modifying his earlier contention that LeMaistre claimed “unanimous backing.”

Returning from LeMaistre’s downtown office—referred to sardonically by UT faculty members as “the Fortress”—Spurr decided to check out regental attitudes. He didn’t have much time: LeMaistre had warned him to sign the letter by 5 pm that afternoon or be fired. He first phoned Erwin, the regent with whom he had clashed most often but also the regent who Spurr felt showed the least regard for LeMaistre’s views on how the UT System should be managed. Spurr had known since the early summer that Erwin wanted him out by the end of this year, but he also felt that Erwin was even more hostile toward LeMaistre. He contacted Erwin, partially to gain information and partially in hopes of finding an ally. The tall, greying regent came to the president’s campus office an hour later, bringing the omnipresent Don Walker once again along as a witness. Erwin soon dashed any hopes Spurr might have nurtured. He discussed the situation in full and friendly fashion, but expressed no sympathy for Spurr’s plight and told Spurr that he would support LeMaistre, whatever the chancellor decided in the affair. Spurr has subsequently charged that Erwin was ultimately responsible for his dismissal.

Spurr went home for lunch, talked over the matter with his wife and returned to his office to place calls to several regents—Shivers, Austin attorney Ed Clark, Lady Bird Johnson, and James E. Bauerle, a San Antonio dentist. He concluded that neither Mrs. Johnson nor Dr. Bauerle had any forewarning of LeMaistre’s action. “At least two had not heard of the action, had not heard it discussed, and expressed themselves as being greatly upset by the matter,” Spurr wrote to Pincoffs on October 16. “A third told me that he was terribly sorry and that he thought I would have made “a helluva good President if they (the regents) hadn’t kept picking away at me.’” That sentiment probably came from Shivers. Spurr’s conversations with at least three of these five regents, coupled with an indirect report on still another regent’s attitude, convinced him that LeMaistre did not have unanimous support. Spurr nevertheless continued to lean toward resigning. He phoned LeMaistre and asked the chancellor to read the proposed letter of resignation that LeMaistre had shown him seven hours earlier. “I told him that I was strongly inclined to write that letter but that I felt that my wife and I both had to sleep on it overnight with regard to the personal effect it would have on our lives,” Spurr recalls. They agreed on a new deadline of 11 am the next day.

That evening Spurr began to have serious qualms about writing a letter that would say, as LeMaistre had suggested, that he resigned for personal reasons. “My friends would ask me, ‘Well, does that mean health?’ and I would have to say no. I had a complete exam by my cardiologist last Friday after the regents’ meeting and passed with no reservations. Well, it became increasingly apparent to me that people would suspect the worst—that I had been caught in some serious wrongdoing—and that I resigned to avoid being exposed.”

Thirty years ago Homer Rainey had faced a similar situation and had concluded “that in the long run it didn’t matter whether I was president of the university, but that the important thing was the manner in which the university was operated.” Rainey eventually “was able to set aside all personal considerations.” Spurr’s resistance to LeMaistre began with personal considerations, but before long he, too, came to believe that larger issues were at stake. Consultation with several close friends cemented his resolve. Spurr held a council of war at his home that night with four members of his administrative team: university vice-presidents Jim Colvin, Ron Brown, and Bob Mettlen, and assistant to the president Don Zacharias.

Shortly before 11 pm, Spurr reached his decision to fight. The issue, as he saw it, was academic self-governance—including the right of campus administrations to make decisions in academic matters free of regent interference. To underscore that issue, Spurr drafted a letter to be sent to LeMaistre Tuesday morning, September 24, advising that Spurr would not resign and requesting full opportunity for review of Spurr’s three-year performance as president.

Time was of the essence on the morning of September 24 for both Spurr and LeMaistre. Spurr placed urgent calls to James W. McKie, Dean of the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences; Wayne A. Danielson, Dean of the School of Communications; Lorrin Kennamer, Dean of the College of Education; law professor Charles Alan Wright; government professor William S. Livingston, and philosophy professor Edwin B. Allaire, asking them to be at his office at 11:30 am. Kennamer was out of town; the rest agreed to come. Spurr intended to ask them to serve on a special ad hoc committee to evaluate his presidency. He would inform them of the reason for his request simultaneously with the delivery of his letter to LeMaistre.

The chancellor also was making phone calls that morning. Two were to professors on Spurr’s list—Charles Alan Wright and William S. Livingston—asking them whether they could be in LeMaistre’s office at 1 pm. Summons also went to business law professor Lanier Cox, student body president Frank Fleming of Dallas (who is close to Erwin) and student vice president Bill Parrish of Houston (who isn’t). But Wright told LeMaistre he would have to cancel a 1 pm class lecture to make the meeting. LeMaistre told him not to do that. Soon thereafter, Spurr’s letter stating his refusal to resign reached LeMaistre. LeMaistre’s office then called those invited to the 1 pm meeting to advise that it had been cancelled. The chancellor decided, without delay, to make good on his threat to fire Spurr and to get the word out to the public. Less than fifteen minutes after Dilly handed Spurr the letter containing the bad tidings, LeMaistre’s assistant for news and information matters distributed the chancellor’s official statement concerning the firing to the capitol press corps.

Why did LeMaistre decide to fire Spurr? The statement handed to the press shed little light on the chancellor’s motives. After citing the regents’ rules to substantiate his authority, LeMaistre said that his confidence in Spurr’s ability to administer the affairs of UT-Austin had been “severely eroded” over the past few months. “This erosion has been accelerated by a generally uncooperative attitude on the part of Dr. Spurr and an effort on his part to discredit the chancellor and System administration through direct contact with members of the Board of Regents,” LeMaistre’s statement read.

There were no specific allegations, leaving the field open for the inevitable speculation which followed. Spurr himself felt that LeMaistre was carrying out Erwin’s orders, or perhaps only his wishes. Some faculty members viewed the firing as LeMaistre’s attempt to consolidate his power, a bold move to become the survivor of a triangular power struggle between the chancellor, Erwin, and Spurr. The elimination of Spurr and the expiration of Erwin’s term as a regent in early 1975 would leave LeMaistre in position to call the shots, not only for the far-flung UT System, but also for UT-Austin, its most important component and certainly the school of greatest interest to the regents. LeMaistre could solidify his position by naming a more docile president, thereby reducing tensions between the campus, the System, and the regents.

Other faculty members interpreted the dismissal differently: they considered Spurr a weak president and believed that LeMaistre wanted a stronger and more decisive leader for the Austin campus. Virtually everyone agreed, however, that Spurr’s direct contacts with the regents had little to do with his dismissal; regental involvement with the daily administration of UT-Austin often assumed monumental proportions, and if Spurr had refused to work directly with the regents, he wouldn’t have lasted as long as he did.

Whatever LeMaistre’s reasons, there was little doubt that once he had publicly committed himself, the regents would ratify his actions. Even Spurr conceded that his firing was a fait accompli which left the regents no real choice as they gathered in an emergency special session on Wednesday, 24 hours after Spurr’s dismissal. Spurr observed that the regents “were not given the opportunity to consider my dismissal. They were simply asked to confirm the chancellor’s authority to dismiss me, which is quite a different question.

“The impulse of anybody who is trained in the corporate world to support management until you fire management is very strong,” said Spurr. “It’s one of the basic axioms. And it’s one that several regents have voiced, and it’s one that by and large we all adhere to. If I have a strong disagreement between a dean and a department chairman, I listen to both sides, I gather evidence, but if the matter is essentially equal, right or wrong, I support the higher man.” Knowing that he didn’t have a chance if the issue was only whether LeMaistre had the power to fire him, Spurr asked the regents to gather evidence on the merits of his case instead of voting immediately to “approve, ratify and in all things confirm” LeMaistre’s action. But a vote to delay would have implied that the regents lacked confidence in LeMaistre’s judgment.

Mrs. Johnson, the only regent to indicate publicly any concern about Spurr’s ouster, could bring herself only to abstain. “We all have ill served the University,” she cautioned, telling her fellow regents that she did not feel she had enough facts to “approve and sanction” LeMaistre’s action in good conscience. Nevertheless, she said she also was unwilling to do anything to undermine LeMaistre’s ability to run the UT System. The vote was taken quickly; it was 8-0 for LeMaistre.

Mrs. Johnson’s high regard for Spurr could well be understood in light of her late husband’s strong support for Spurr’s efforts to promote recruitment of minorities to the UT faculty, staff, and student body. Her abstention may also have been influenced by one of those tortuous interrelationships which often characterizes Texas politics: Spurr’s lawyer, Sal Levatino (a former attorney for the UT System) is in partnership with Jerry Nugent, whose brother Patrick is married to Mrs. Johnson’s daughter Luci. Jerry Nugent was an observer at the regents’ meeting.

LeMaistre, tense but matter-of-fact, told the regents that he had relieved Spurr because of declining confidence in his administrative decisions. Significantly, LeMaistre omitted any reference to his earlier charge that Spurr had tried to discredit LeMaistre through direct contact with individual regents. When the regents had gathered privately, immediately before going into public session, Vice Chairman Dan Williams of Dallas said he would offer the resolution ratifying LeMaistre’s decision, Jenkins Garrett, a Fort Worth attorney objected to a sentence charging that Spurr had gone around LeMaistre to try to undermine the chancellor with the regents. Three other regents joined in Garrett’s objection so the sentence was deleted.

Perhaps the regents felt LeMaistre could not support his accusation. More likely, however, Garrett was aware that he and other regents had gone around LeMaistre to deal directly with Spurr. In fact, it was Spurr’s insistence on going through channels on a matter of special concern to Garrett that may have cost Spurr Garrett’s support on the weekend preceding the firing. Garrett’s displeasure arose from what he considered Spurr’s failure to assure financing this year for continued acquisitions and cataloging for the Special Collections in the Humanities Research Center (HRC). Garrett, whose hobby is book collecting, was already irritated by the way Spurr had worked out the management of the HRC after former chancellor Harry H. Ransom relinquished his responsibilities as Coordinator of Special Collections on September 1.

Garrett favored continued funding of special collections by special grant from the regents. Without informing Garrett, Spurr called deputy chancellor Walker in early September and suggested that “the best way of taking care of the needs of the HRC and other special collections would be through the regular budgetary process.” This would have put Spurr in stronger position to control the amount spent for HRC, and would have weakened the regent’s role. When Garrett phoned Spurr for a progress report on HRC on September 19, Spurr in turn telephoned Walker and found that his recommendation had not gone forward to LeMaistre. Spurr phoned back to Garrett, and Garrett exploded.

Alarmed by Garrett’s anger, Spurr approached him the next morning immediately before the regular monthly regents’ meeting. “I asked Mr. Garrett whether I could meet with him after the meeting to explain my actions,” Spurr recalled. “He replied that the matter was out of my hands and would be handled directly by the regents and the System administration.” With that curt rebuke, Garrett coldly terminated the conversation and turned away from Spurr. In an informal executive session later that day, Garrett expressed his displeasure with Spurr. One of those present recalls that Ransom, the man who made the Special Collections world renowned, was “very much upset” at Spurr’s effort to change the management of the collection.

The HRC controversy was not, in itself, of sufficient consequence to warrant Spurr’s dismissal, but it is significant as an illustration of three major factors that led to his downfall:

• the insistence of the regents on injecting themselves personally into administrative decisions which Spurr considered his responsibility;

• Spurr’s apparent failure to stick to the exact procedure he agreed to follow once he became involved in working with regents on a quasi-committee basis on problems like HRC funding and management;

• Spurr’s strong disagreement with individual regents over spending priorities.

Spurr says the HRC problem was one of the reasons LeMaistre gave him in demanding his resignation. LeMaistre told him he had spent most of Saturday, the day after Garrett had criticized Spurr to the other regents, drawing up a list of reasons for the firing. So it appears that LeMaistre either had made up his mind already to get rid of Spurr or the events of the Friday executive session crystallized that decision. There is no demonstrated evidence that Erwin directly encouraged LeMaistre to act at that time.

Spurr concedes that he cannot prove it, but he believes nevertheless that Erwin was a major factor. Spurr probably is correct in this respect. Without ever making any direct demand, Erwin made it clear he wanted Spurr out. Erwin was so explicit on this point that some of his close associates—especially students whom he befriended—were talking about it as early as last May. One student recalls that Erwin “gave me a pretty good indication that Spurr would be out by the end of the year.” The student was not surprised because he had always understood that “Spurr was not the man Erwin wanted” as president. The student said Erwin complained last May that Spurr was not shooting straight with him, a reference to Spurr’s failure to gain admission to the UT Law School for a friend of Erwin’s.

Erwin denied after the dismissal that he had ever pressured Spurr for a student’s admission. Spurr subsequently backed off from any implication that Erwin had pressured him directly, but Mettlen, Spurr’s assistant, said there definitely was pressure on the president’s office.

Erwin further resented the fact that Spurr consulted with Shivers but not with Erwin on selection of the new law school dean, Ernest Smith. Spurr says it was at LeMaistre’s suggestion that he went to Shivers, not because Shivers was a regent but because he was chairman of the life trustees of the Law School Foundation. He says Shivers agreed with him that he could not go through the regents on the politically sensitive appointment. At Shivers’ suggestion, Spurr asked Chief Justice Joe Greenhill of the State Supreme Court, Attorney General John L. Hill, and the incoming president of the State Bar of Texas, Lloyd Lochridge, to help interview the candidates recommended by the faculty-student selection committee.

Erwin, whose differences with retiring law school dean Page Keeton were well known, approached Spurr and asked whether he would mind telling who was on the list recommended by the committee. “I said, ‘Frank, I prefer to be in a position where I can tell the faculty and students that I have not discussed the matter with you until after I have made my choice,’” Spurr recalls. “And Frank laughed and said, ‘I understand the politics of it.’” Erwin’s amusement was short lived.

Spurr had also aroused the ire of another influential regent, Ed Clark, over use of university funds for a World Energy Conference on the UT-Austin campus in 1975. Clark was pushing hard for the conference, which Spurr also favored but gave lower priority than academic needs. The two were on a collision course at the time of Spurr’s dismissal. Clark was also indignant that Spurr had appealed to Governor Dolph Briscoe in mid-July to consider a special legislative session to give all state employees, including college personnel, a pay raise. Clark, once regarded as the premier Austin lobbyist, was angered because Spurr had injected himself into political lobbying, an area reserved as a matter of policy to the regents and the chancellor. What Clark did not know was that Spurr had consulted with Erwin and LeMaistre, and they had approved his letter to the governor. Indeed, Erwin had even offered suggestions for improving it.

After the regents ratified the firing, LeMaistre refused to elaborate on his original statement, and the regents also rejected demands for a public explanation. LeMaistre wrote the select student-faculty committee investigating the incident that he was withholding a bill of particulars on advice of counsel. LeMaistre promised to release a comprehensive public statement “after it has been cleared by legal counsel.” Governor Dolph Briscoe added the weight of his constitutional authority to force LeMaistre to make good on his promise. Apparently the preparation of LeMaistre’s explanation was a tedious, ticklish, legal process. UT System lawyers pored over the draft, attempting to protect LeMaistre from a suit for damages arising from statements that might be deemed professionally harmfully to Spurr, as well as to make certain that the chancellor’s reasons would stand up as a valid basis for firing the president. (The statement was scheduled for release in November, after Texas Monthly’s press deadline and more than a month after Briscoe’s ultimatum.)

Spurr’s sudden dismissal, combined with LeMaistre’s sketchy explanation of it, made Spurr into something of a hero at the UT-Austin campus. His public image had previously been that of a mild-mannered, almost Milquetoastish man frequently under fire from students and faculty; suddenly he blossomed in the aftermath of his firing into a resolute, occasionally earthy champion of academic self-government. When he accused Erwin—always cast as the devil in such matters—of engineering his downfall, the bespectacled, balding Spurr became an instant campus martyr. He touted his own “independence and vigor in pressing for what I believed to be right in the inner councils of the System” as one of the underlying reasons for his dismissal. And he told a slightly titillated, faculty audience in his farewell address that when he accepted the presidency, his philosophy was that “I wasn’t going to—if I may say it—kiss anybody’s ass as a university administrator.” Having by his own evaluation made good on that pledge, Spurr now is a tenured professor enjoying the pleasure of teaching and research. His is a comfortable martyrdom.

As for the university itself, it appears to have survived the loss of its president with little of the wrenching dislocation of the Rainey episode. The regents of that age represented the essence of political and economic power in Texas; they thought they could get away with anything. They failed to recognize that the university was part of a larger, national academic community. Today’s regents learned that lesson well. They are far more careful and more subtle than their predecessors of 30 years ago. Every controversial action is invariably supported by academic arguments and a legal brief. At the moment, the regents are also blessed with good luck: they are not dealing with the activist students of the late Sixties, but with a different breed altogether. And the student body president is on friendly terms with Erwin, a situation which would have been unthinkable four years ago. All the signs indicate that the university will survive Spurr’s firing far better than it did Rainey’s.

Erwin, whose life has been wrapped up in UT affairs for the past twelve years, is not expected to return to the Board of Regents next year. For once he does not have the governor on his side, having supported Ben Barnes’ abortive race against Briscoe with his customary gusto. But speculation abounds that Erwin would like to stay on, perhaps become UT System chancellor, UT-Austin president, or legislative lobbyist for the System. None of these positions seem likely to go to him.

But the thought must be disturbing to much of the bruised UT academic community. And to LeMaistre.

- More About:

- Austin