The first time Ann O’Connor Williams Robinson laid eyes on Jim Harithas, he was pinning a guy to the ground.

It was 1974. Harithas had recently moved from New York to Houston to direct the Contemporary Arts Museum. That day inside CAM, Harithas was removing a maquette of one of the painter Leo Tanguma’s murals to make way for his first show at the museum, and Tanguma wasn’t having it. He punched Harithas, and they were tussling on the museum’s loading dock when Ann walked by.

A striking, stylish brunette, Ann was studying art history at Rice University and owned an art gallery next door to the museum. She had macho culture in her blood, too, as a scion of one of the state’s oldest ranching, oil, and gas dynasties. An O’Connor from South Texas, she grew up roping and riding and sneaking out of her family home near Victoria to play poker with the cowboys down at the pool hall on the Refugio highway.

Jim, with the upper hand in the fight, looked like her kind of maverick. He was handsome in a geeky way—wire-framed glasses, receding but abundant curly hair, and a mustache as thick as a wooly caterpillar. Decades later, Ann would grin and let loose a laconic, smoky chuckle when she described that moment and remembered wondering, “Who is thaaat?”

So begins the story of a renegade art power couple the likes of which Texas might never see again. Years before the state’s major museums presented politically or socially conscious fare, Ann and Jim Harithas founded the Art Car Museum (in 1998) and the Station Museum of Contemporary Art (in 2001). Both spaces operated as “activist” institutions, supporting artists who weren’t afraid to push visitors outside their comfort zones. In 2016, Ann opened one more, the Five Points Museum of Contemporary Art in Victoria, as a gift to her hometown.

The Harithases commissioned much of the work their museums displayed. Unlike some of the state’s other institution-builders, though, they had little interest in amassing or sharing a collection. Nor did they etch their names onto their buildings.

In fact, the couple disliked bureaucracy and rules so much that they didn’t even establish a foundation to keep their museums going in perpetuity, or leave instructions for their heirs. It was as if they knew an era would end with them. Ann died in December 2021, at the age of eighty, followed by Jim, last March, at ninety, leaving behind a complex estate that could take years to settle. Along with the three museums, they owned multiple homes and personal collections, most of it funded by her family’s money. And they had seven kids between them—her four, from two previous marriages, and his three, from his first marriage.

Molly O’Connor Kemp, one of Ann’s daughters, said the family is still debating how to preserve their parents’ legacy. Much to the chagrin of the state’s art community, the Station—the crown jewel of Harithas World—has been “on hiatus” since November 2022. Kemp and her siblings established a trust to pay for two years’ worth of programs at Five Points and the Art Car Museum that Ann planned before she died. They are most keen on keeping the Victoria museum open.

Kemp made it sound as if reviving the Station wouldn’t make sense without the founders leading it, because shows there grew out of Ann and Jim’s relationships with artists. The Art Car Museum and Five Points are more self-sufficient, but there’s still an issue of maintaining the Harithases’ vision. The heirs have considered showing some of the couple’s collected work “because that’s something we can do easily,” Kemp said, “but without it being, like, all in the past.”

Five Points sits within a former car dealership so immaculately converted that many first-time visitors are shocked to find it in rural South Texas. Aesthetically, Victoria’s museum blends the vibes and missions of the Harithases’ Houston spaces, but it has something they do not: a program called the Manhattan Art Program that’s coordinated with area schools.

Five Points was quiet when I visited last spring to see a show that might have mortified its founder. Ann was so private that friends and family often described her as a recluse. Jim was the frontman by default. “The Creative Era of Ann Harithas,” which reopened Saturday at the Art Car Museum, shifts the focus, suggesting the depth of a story that was not told during her lifetime.

The show is a revealing retrospective of the collage art Ann made throughout her life and kept close to her chest. She learned her first words by peering at scrapbooks of collages her great-aunt Mettie Harbison constructed with homemade glue. Years later, collage remained Ann’s language of choice. She occasionally lent pieces for exhibitions, but her work was so personal—more like a diary—that she rarely sold it, even to her kids. (Kemp remembers how her mother once took back a piece Kemp had bought.)

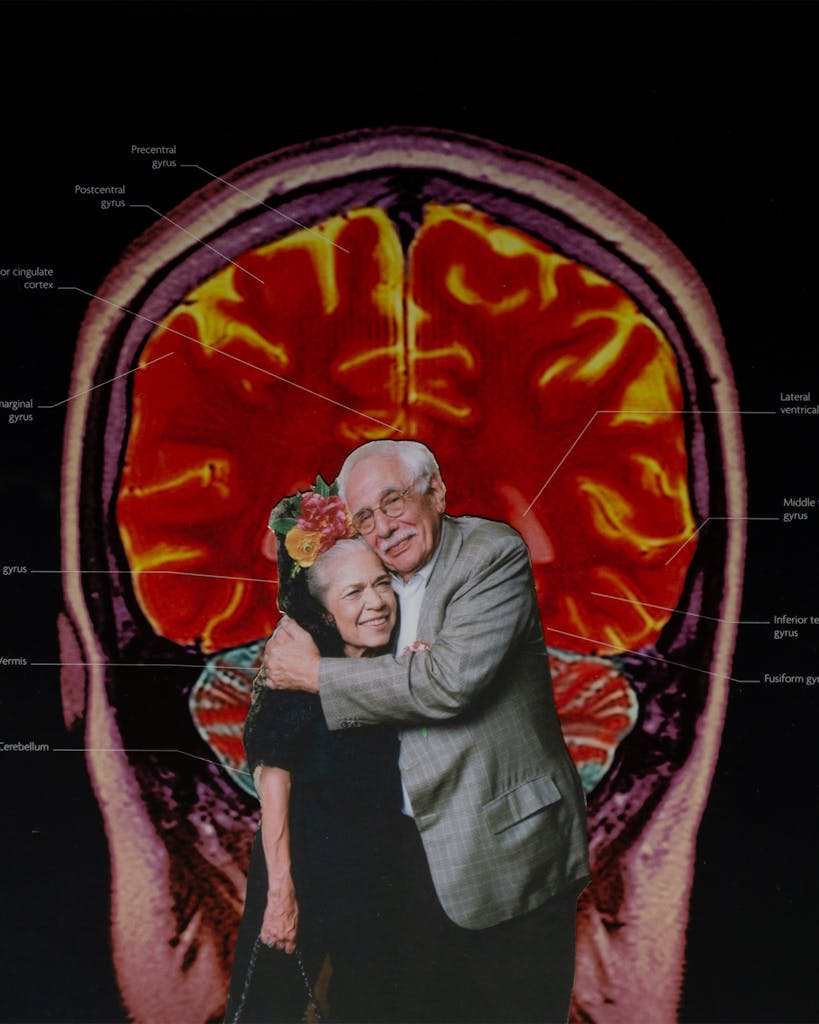

The collages fuse Surrealism and Minimalism, and some are made with as few as three cut-out images from magazines. Ann experimented with digital techniques to make large prints but also produced many small collages in series. Collage was never just idle business for her. Constructing her own visions of reality based on Southwestern culture, high fashion, religion, spirituality, politics, and class structures, she had a sharp nose for irony. Ann created her Memory series of self-portraits after suffering what appeared to be a stroke in 2012. The process of regaining her memory was aided by juxtaposing pictures of herself through the years with images of menacing creatures and scans of her brain.

In the Harithas tradition, the show also features Swamp Mutha, a sumptuously collaged art car Ann made with the late Jesse Lott, one of several artists she considered family. The show’s videos illuminate how Ann was on her own path as a curator and patron. During long sojourns in New Mexico, she immersed herself in Native American culture and spirituality. In New York, she befriended Terry Dintenfass, a dealer who represented contemporary artists shut out of the mainstream. “She almost had a calling to join, to be a part of that, and it took all of her interest,” Kemp told me. “She wanted to bring that back to Texas.”

Ann had a special place in her heart for artists who came from humble beginnings. Along with Lott, she championed the multimedia artist Travis Whitfield. Her patronage changed his art, Whitfield told me; she paid his way to a famous printmaking workshop to increase his income, and without asking if he needed it, she rented an apartment for him in Houston.

The conceptual artist Mel Chin, who grew up in Houston’s Fifth Ward, famously walked into Ann’s gallery fresh out of grad school, hauling a four-foot ceramic work he called Western Dynasty. It resembled an ancient Chinese vessel but was decorated with a longhorn motif. He set it down and told her, “I want to show here.” In her deadpan way, she shot back, “Well, you are.”

Ann fell hard for art car counterculture after seeing the work of California sculptor Larry Fuente in 1978, the year she and Jim married. Never one to start small, she commissioned Fuente to build her first art car (there would be dozens over the years). Fuente’s heavily beaded and faux jewel-crusted Mad Cad debuted as a centerpiece of “Collision,” a show Ann curated at Lawndale Art Center in 1984. (In those days, Kemp was attending the upper crust St. John’s School and could always spot her mom’s dazzling, funky art cars among the Mercedes Benzes and Land Rovers that lined up each afternoon. “She was definitely in her own element,” Kemp said.)

The dynamic, anything-goes oil-boom years were a time of foment and wild experimentation across the Texas art scene, and Ann was all in with any work that promoted community. Along with supporting Lawndale, she helped Lott and Rick Lowe launch Project Row Houses and organized shows in California and New York to promote Texas regional talent. For her cheeky 1980 “Gun Show,” she presented art made with weapons at an actual gun show near Los Angeles. “It was the kind of thing that shifts peoples’ minds—taking things out of context and putting them into a new context that shook the normal ecosystem,” said the artist Susan Plum, one of Ann’s close friends.

You can understand why Jim, too, was smitten.

The son of erudite Greek immigrant parents who instilled his interest in politics and social justice early (his father was a U.S. military judge), Jim spent his youth between the U.S. and Germany. He got through college in fits and starts, quitting early to become a painter. He lived hand-to-mouth in New York before the Army drafted him and sent him to France for two years during the Algerian War. Landing his first jobs as a curator in the early 1960s, he befriended some of America’s most influential artists and quickly gained a reputation as an innovative agent of discovery. The sculptor Barnett Newman convinced him to forget about the big museums in New York and go where he could have a greater impact, advice that would shape his entire outlook.

By his late thirties, Jim was directing the prestigious Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. That also put him in the thick of civil rights and anti-war protests, and his antiestablishment mindset didn’t sit well with the Corcoran’s board. He fit in better with his next gig as director at Syracuse’s Everson Museum of Art, where he gave Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Joan Mitchell, and Norman Bluhm their first solo museum shows and established one of the nation’s first art programs for incarcerated persons. When the CAM came calling, East Coast friends tried to discourage him from taking the job, certain that moving to Texas—a cultural wasteland as far as they could tell—would derail his career.

For a few years, Newman’s advice to blaze trails beyond New York seemed golden. Jim put the CAM on the map with his early support of Texas artists who were among the region’s first blue-chip contemporary talents, including Luis Jiménez, James Surls, John Alexander, Terry Allen, Mel Casas, Julian Schnabel, and Dorothy Hood. While Ann became the biggest benefactor of Jim’s shows at the CAM, and they collaborated on an exhibition of her kachina collection for the museum, his relationship with CAM’s board grew combative. When they hired a business manager to rein him in, Jim resigned. He’d had it with museum bureaucracy. Museums were failing people; a new model was needed, he insisted.

During the first years of Ann and Jim’s marriage, the blended Harithas family led a peripatetic life. Jim took time to reset, in his way, by delivering medical supplies to war-torn regions of the world. He and Ann also took the kids on extended trips to Mexico, lived in Rockport for a year, and migrated briefly to New York’s Upper East Side. All the while, their shared ideas about what a museum should be developed further.

They founded the Art Car Museum to promote the vernacular art form as an expression of freedom that is a “God-given American right,” as Jim put it in his Art Car Manifesto. Set within a low-slung metal building near the Heights, that space dominates its block like the road warrior of museums, surrounded with a concertina wire fence and topped with spiky metal sculptures. The interior aesthetic is gutsy, too.

Jim and Ann welcomed debate and urged the artists they worked with to think as hard as they did. That’s a big part of what the Station was about. There was a reading room at the front door, and films and lectures accompanied every show. The Station is where Ann and Jim collaborated most as curators and patrons, Kemp said. “I think she gave him the steering wheel, but she was right there with him in the front seat.”

Many of the Station’s shows grew from Jim’s long forays into unsettled parts of the world in search of artists he thought were doing urgent, necessary work. “He had this unique ability to find artists who were saying something he thought could apply to the rest of the world,” Kemp said. Shows featuring local and regional artists also addressed issues of justice—democracy, censorship, repression. Aside from their purposefulness, exhibitions at the Station always looked refined—they were expertly designed and lit, with walls often reconfigured. The Station may have marched to its own beat, but its shows were as well-produced as those of any major museum.

Jim and Ann expected their artists to challenge them, Mel Chin told me. When he was sharing work in progress with Jim, he knew to expect “a period of questioning what a piece meant by the emotional response it generated, based on his deep knowledge of art history and what works can bring to society.” Ann, meanwhile, would “ever-so quietly meditate” in front of works to absorb them. Chin knew he’d hit the mark if a piece surprised them both. His standard for new works, even now, is asking himself, “What would Ann and Jim think?”

“There was a political radicalism about Jim, but he was deeply critical and not frivolous,” Chin said. “He liked to sit in a hard chair, not a soft chair, at a table, and read deeply and try to understand things.” Jim also kept a punching bag in his home office for those times when he needed to work out ideas.

When she was younger, Ann could breeze through Neiman Marcus on a Christmas shopping spree that made heads spin, flaunting the rules with a cigarette in her mouth that no one dared question. She had homes all over the place and traveled by Lear jet. But she rarely broadcasted her wealth. “You’d never know she had a dime,” said Travis Whitfield. During their heyday, Ann and Jim often took pals dancing at Gilley’s in Pasadena or Schroeder Hall in Victoria. Life with the Harithases was often a party, and Ann could be the life of it.

Ann approached every part her life with “a collage frame of mind,” said Maurice Roberts, Five Points’ chief curator. “She’d take these disparate components, whether they were people or artists or styles, together to create a synthesis.” He was her first digital assistant in the 1980s, and as with other friends she loved, she always found ways to keep him in her orbit. Roberts said, “We’re all like her living collage.”