Roger Winter is a significant figure in Texas art history, a painter of profound sensitivity and technique. For a period that’s now almost forgotten, in the late seventies and eighties, he was one of the most prominent artists in the state. His success in that era coincided with a body of work that featured pastoral scenes of rural Texas and realistic depictions of what he calls “the good life” in the tony Dallas communities of Highland Park and University Park. Winter’s subject matter during what might be called Dallas’s J.R. Ewing era, from wealthy children at leisure to fence rows and cattle, reflects a familiar, if old-fashioned, role for a master painter: that of capturing the lives and bucolic dreams of the collecting class.

Winter, now 86, left Dallas behind three decades ago, moving between the Hill Country, Maine, New York City, and New Mexico. He moved on thematically, too, to a variety of other subjects and styles, but Dallas still loves him after all these years. The exhibition “Dallas Collects Roger Winter” is on view through November 28 at Kirk Hopper Fine Art, and Texas A&M University Press has published Susie Kalil’s new, gorgeously illustrated book The Art of Roger Winter: Fire and Ice, underwritten by a list of notable Dallas names. Kalil’s book demonstrates that there is much more to Winter’s six-decade oeuvre than his Texas paintings of the seventies and eighties, and more, also, to his work of that period than immediately meets the eye.

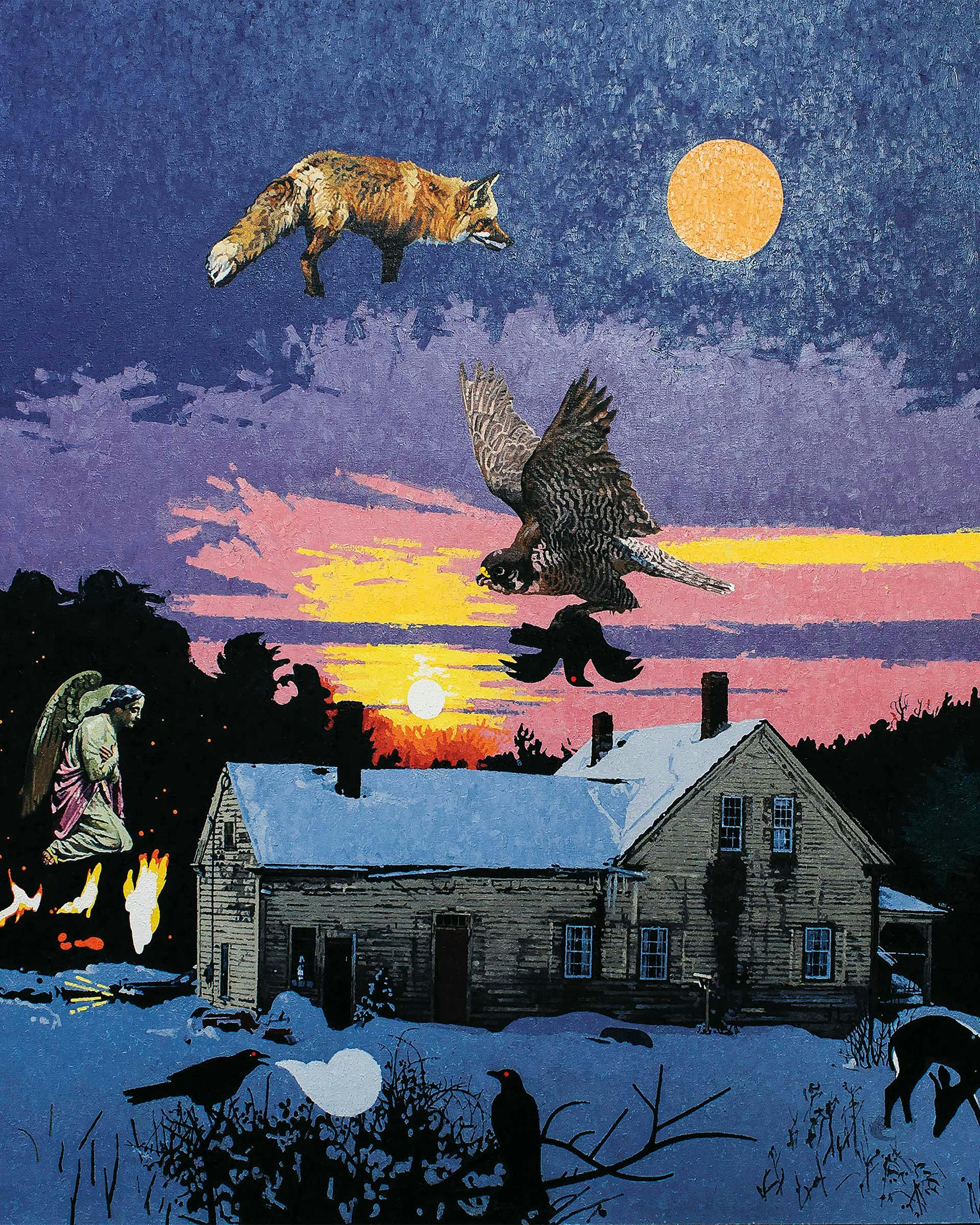

Kalil introduces Winter in her book as “a die-hard romantic whose reflection on the passage of time conveys a bittersweet awareness of the fragility of beauty, which, for him, is synonymous with sentiment.” Heady prose, perhaps, but observe how those abstractions—time, awareness, fragility, beauty, sentiment—twist together into a tangle as we try to make sense of them, and you’ll get an idea of how Winter uses paint and image to funnel interior experience onto the canvas.

Winter describes his philosophy in more plainspoken terms. “I think it’s about empathy,” he says. “You have to become what you’re drawing or painting.” When it comes to depicting people, his aim is timelessness: “A portrait should look like someone looks all their life—not just at a certain age, but how they look at five and fifty years of age.”

Winter grew up poor on the outskirts of Denison, eighty miles north of Dallas, during the Great Depression; he nearly died at age two from dust-induced pneumonia. His was the only white family in a predominantly Black neighborhood next to the train tracks. Winter remembers catching glimpses of the well-dressed city people and white tablecloths of the Texas Special passenger-train dining car as it passed his house at Christmastime; he’d gaze out the window, dreaming of a different life, as it rattled by. His own family was troubled, prone to arguments and violent fights. He once had to wrestle his mother to keep her from harming herself with a razor.

Winter attended UT and briefly served at Fort Bliss in El Paso before settling in Dallas with his wife Jeanette for nearly three decades, beginning in 1961. There, he quickly discovered a bohemian, art-hungry community of friends in Oak Lawn, led by legendary museum curator Douglas MacAgy. Winter is the last surviving artist from the era-defining MacAgy show “One i at a Time” (1971), a survey of the Dallas avant-garde at the Meadows Museum at Southern Methodist University.

Winter’s style began to mature in the late sixties and early seventies. He explored domestic themes, copying realist figures from various family photographs and juxtaposing them on the same canvas but with widely varying color palettes that emphasize the lack of organic connection between the characters. On the rearmost layer of the canvas there is often a flat, simple house. In this period, it seems, Winter was working through memories of his dysfunctional childhood home and drawing on it to construct a different geometry for the family he was raising with Jeanette.

“He understands the space between people, how we long to move through it,” Kalil writes of Winter’s art in this era. “Real life, its dreamy past and the daily ordinary present, with its deep roots and complex possibilities, is his subject.”

From 1963 to 1989, Winter taught at SMU, training a number of successful artists, most notably Julian Schnabel, who went on to become one of the most famous American artists of the 1980s and later directed two Oscar-nominated films. Winter was by many accounts a wonderful teacher—he often welcomed students into his home to discuss art—and the openness to different styles of painting required in a good mentor seems to have made a mark on Winter’s own work. His paintings changed during this time, shifting toward realism as he attempted to make a single, continuous scene evoke the same depth of feeling he’d conjured in his earlier layered-image paintings.

For subject matter, he gradually turned to what was at hand in his new life as a University Park professor now socially connected to well-off collectors. Dallas’s economy was booming at the time, thanks to the rapid growth of the oil industry, and Winter’s friends were living well.

“By the 1980s Jeanette and I had become social friends with art collectors and company who were of a higher economic class,” Winter tells Kalil. “So that extended my subject matter, without an ounce of criticism, beyond the world I’d known as a child. I grew up thinking that wealthy people would sic their dogs on you.”

Winter is especially effective in capturing the cosseted innocence of well-off Dallas kids in paintings like Highlander Band (depicting an outdoor marching band practice in which his son Jonah plays clarinet) and Horchow Sisters (in which the daughters of mail-order tycoon Roger Horchow relax in a florid backyard pool area). There is more than a hint of the idyllic in Winter’s presentation of these subjects, and it’s up to his viewers to decide if they’re encountering a dream come true or a daydream vision that turns to squiggly lines if they step too close to the canvas.

In the early eighties, Winter was promoted to full professorship at SMU, sold out three shows at New York’s Fischbach Gallery, signed a contract to write a drawing textbook that is still in use at university art departments, and won a commission for an imposing ten-by-twenty-foot landscape painting (Silhouetted Trees) that still hangs in the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. His style at this point was realist with a complicated emotional vocabulary of brushstrokes, one that Kalil describes as “a virtuosic shorthand of flicked, dragged, stippled strokes that leave behind scintillating crests of paint.”

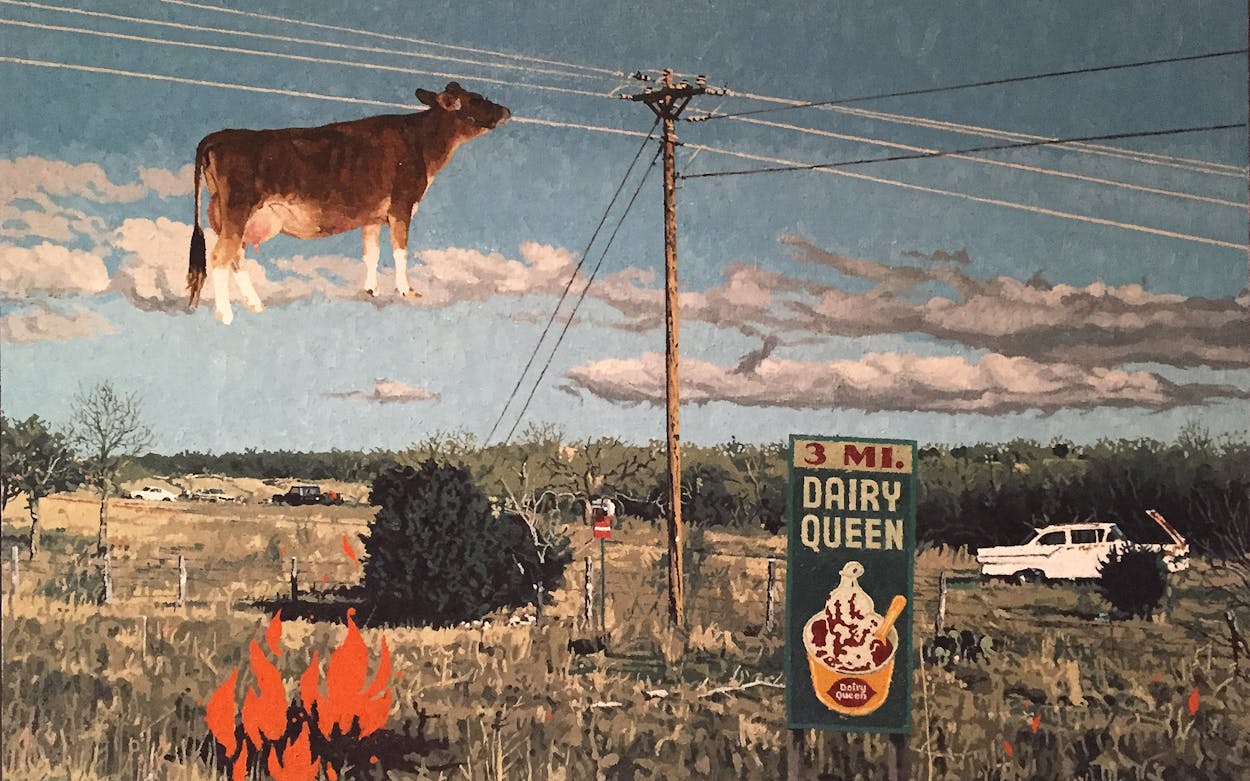

Landscapes such as Silhouetted Trees and pastoral scenes of cows and fence rows, which Winter produced in quantity in this era, seem to operate in thematic parallel to his “good life” paintings of leafy Dallas enclaves. Winter seems to be thinking in paint about where he came from to arrive in this place of prosperity, and what it meant to traverse those distances. It’s a question that also must have felt relevant to many in Dallas who bought and commissioned his work. Looking back, Winter tells Kalil that though he understood that the subject was seen as “hokey,” he “knew the shape and attitude of the cow better than any farm animal,” thanks to his dirt-poor Denison youth.

Winter had arrived at something like the top of the Texas art world, but he very quickly grew restless. He and Jeanette began spending more time in New York City, which became, alongside Texas, a second muse for Winter. Eventually, in 1989, they left Dallas for good. Winter recalls attending the funeral of an older artist friend and hearing eulogies about how much he’d helped the Dallas art scene. “I didn’t want that on my epitaph,” he tells Kalil.

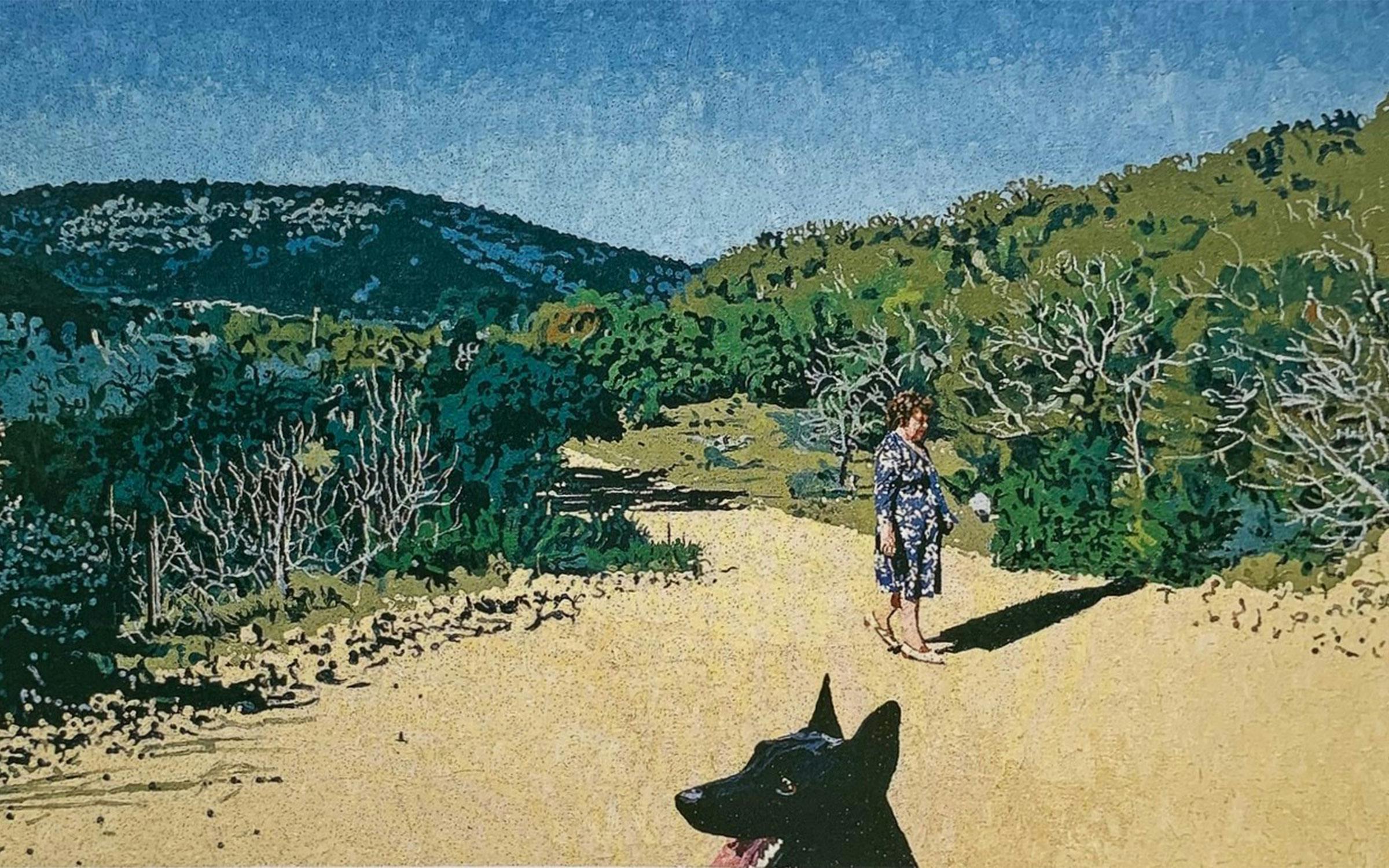

The Winters moved first to Maine, then back to the Texas Hill Country town of Pipe Creek, and later to Santa Fe and New York City. Winter seems to have taken his departure from Dallas as an occasion to rediscover the surrealism of his younger days, and though it did not start off auspiciously—he was dropped by Fischbach in the early nineties—he has had an extraordinarily prolific older age, exhibiting regularly and producing varied bodies of work on subjects like glacial polar landscapes and New York City subway riders. “Knowingly imitating myself is number one on my list of deadly sins,” he says.

The spare landscape of West Texas became another muse for Winter in works that vibrate with intimations of mortality. His 1994 Texas Odyssey #1, for example, depicts the surreal and lonely scene of a woman sweeping the side of a desert highway with a broom, dwarfed by the vast expanse of sky above.

Today, Winter is perhaps best known for his contributions as a teacher—his most recent claim to fame is having given a one-on-one studio critique to former president and aspiring painter George W. Bush, in which Winter convinced Bush to try painting some of the world leaders he had met over the years. Kalil’s book is part of a larger effort to further recognition of Winter’s accomplishments as a painter.

Winter’s constantly unfolding technique and full-hearted commitment is never more evident than in the roughly one thousand paintings and drawings he has made of his wife Jeanette over the years. Winter has approached the subject of Jeanette through all the various styles and composition techniques he’s adopted and discarded over his long career, beginning when he met her as a model in his painting class in graduate school, now 62 years ago. Many read like drawing practice or quick-sketched experiments made during quiet evenings at home, but others are fully realized paintings that speak to key thematic concerns of Winter’s—from the 1960s, when they were first making a home together, to recent years as they have both entered older age.

Kalil describes the Jeanette series as “a constant questioning of what it is to truly see another person and what is possible to depict. Each drawing or painting is a fresh collision between this questioning and the woman in front of him.” This observation describes much of Winter’s art on other subjects, as well. Each work is a fresh collision between the world as he sees it and the question of what is possible with a little paint and a lot of empathy.

Winter, again, says it best. “You fall in love with someone more than once,” he says, speaking of the Jeanette series. “I fell in love with her again and again when I did the drawings and paintings.”