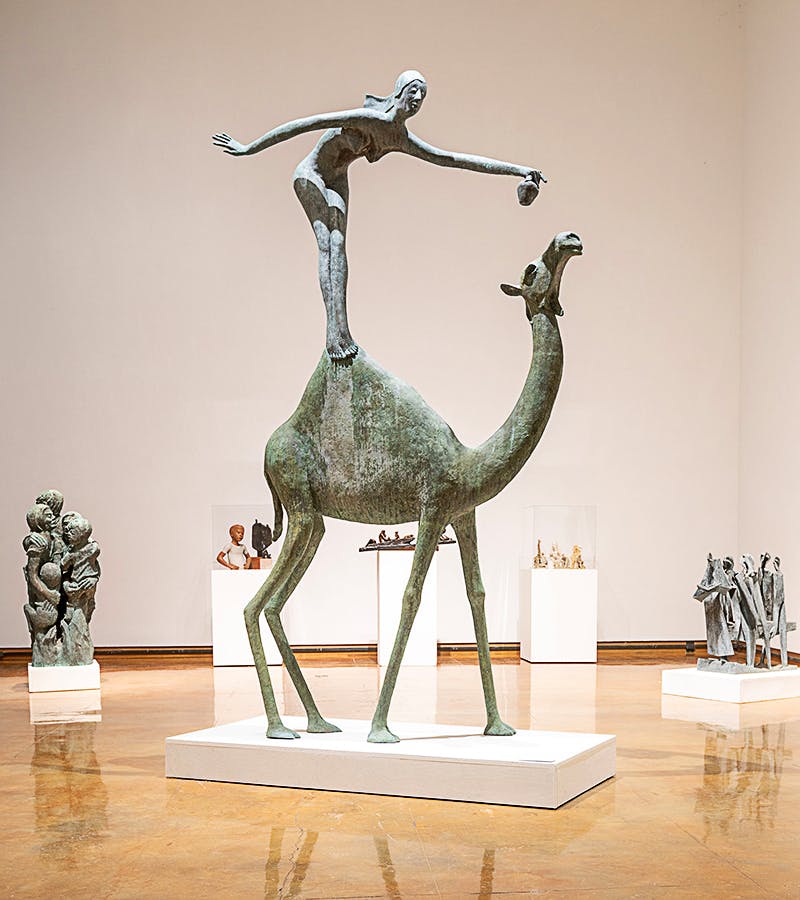

Right in the heart of industrial Beaumont, a thick blanket of untamed greenery obscures a plot of land. Any onlooker would be forgiven for thinking the lot’s abandoned, but walk through its gates and you’ll see, hidden among the wild thicket of weeds, shrubs, and oak trees, a garden teeming with sculptures that seemingly sprout out from nowhere. One depicts two men sitting close to each other on a bench, talking to their dogs but not to each other; in another sculpture, the biblical figure Eve stands playfully on a camel’s hump, dangling an apple over the drowsy creature’s mouth. Flanked by rusty Greek columns, dozens more bronze sculptures of humanlike figures stand guard around the yard.

Overlooking all of this is southeast Texas sculptor David Cargill’s angular, mid-century-modern home and studio. This statuary, which he’s maintained since he first started building his house in 1957, is where the sculptures in Cargill’s recently opened solo exhibition, “Life Is a Long Way,” permanently live. On view until March 7 at the Dishman Art Museum on Lamar University’s campus in Beaumont, the show is a retrospective of the work he’s done over his career. With full-size pieces and scale-model replicas of sculptures he’s still waiting to cast, the exhibit lets patrons catch a glimpse into the distinctive world hidden behind Cargill’s fence.

One December day, Cargill, clad in a worn Dickies jumpsuit, sinks comfortably into a chair in his living room. Sculptures ranging from fifteen-feet-tall wooden totems to small plaster modellos watch us from every corner of the room. Everything Cargill does is deliberate, from the artwork to the way he answers my questions, taking long pauses while searching for the right words. “No matter what your field is, it takes your whole life,” he says, pouring me a cup of black tea served alongside a slice of homemade butter cake. “It’s a long journey, and I don’t know if there’s a destination necessarily.”

At ninety years old, Cargill has built an extensive portfolio of sculptural work throughout his long life, creating for public, commercial, and religious entities, for galleries, and for himself. “We lived sort of a mixed life,” he says, referring to the work he and Patty, his creative and life partner, often did together. The two of them initially made the bulk of their earnings as artists by completing projects for other people. “If you think about it, most artists think about galleries and museums. We did a little of that, but mostly we were doing commissioned work. So we were solving someone else’s problem,” Cargill says.

One need only take a quick drive around Beaumont to see some of Cargill’s extensive CV come to life. A six-foot bronze bust of the legendary Texas politician and poet Mirabeau B. Lamar, which Cargill created on commission in 1965, stands in the middle of Lamar University. Strolling through the plaza between Beaumont Civic Center and City Hall, one will see Winning, a towering stainless steel sculpture from 1982 depicting three men hoisting a fourth on their shoulders in victory. After perusing Cargill’s permanent collection of fine art at the Art Museum of Southeast Texas, walk outside to see Men of Vision, a seven-and-a-half-foot wide bronze statue he completed in 1995 that portrays the four Rogers Brothers mid-stride. (Ben and Dr. Sol Rogers founded Texas State Optical in the thirties, and eventually the four brothers amassed a fortune, part of which they used to help fund cultural and medical institutions in Beaumont and beyond.)

These are just a few examples of Cargill’s public art, flecked all across southeast Texas—stalwart monuments to people both iconic and mundane. “He’s very well known because he’s still very active in the art community here,” says Dennis Kiel, director of the Dishman Art Museum, who worked closely with Cargill to select pieces for the show from his massive collection of sculptures. “And I’m sure all the people who’ve seen his work know who he is.”

But if the menagerie of bronze, terra-cotta, wood, and marble figures crowding his house is any indication, Cargill didn’t limit his creative output to what’s available for the public to see. “In the interim, I was always making things, because that’s what I like to do,” he says, adding: “I think I came to realize that was my goal. Because I like to make things, I made things.”

Born in Huntsville in 1929, Cargill moved with his family to Beaumont when he was six years old; his father was transferred there for his job as an electrical engineer at Gulf State Utilities. As a child growing up amidst the stifling heat of southeast Texas, David needed to keep his hands busy. “When I was young, I was always looking for something to do,” he remembers. “I was bored stiff in the summertime, before I got to the age of getting a summer job.”

Cargill didn’t hail from a family of artists, and there were hardly any working artists in Beaumont at the time. So his tendency to channel his boredom into artistic endeavors wasn’t spurred by a desire to lead a mystical, creative life. If anything, making art became a way of simply passing the time. “I painted because it was just something to do, and I had made some sculptures,” he says.

After graduating from high school, Cargill began his collegiate career as a premed student at Rice University in 1946, but quickly realized it wasn’t for him. “I got to thinking, ‘My goodness. I got to do this for four years, then I got to do medical school. Then I’ll have to do a residency, and then something else. I’ll be an old man before I’m doing whatever I was doing!’” Cargill exclaims. “I thought, ‘This is going to take too long.’” Recognizing his penchant for making things, Cargill tried to tack on a second major in architecture, but the school registrar wouldn’t allow him to do so.

It wasn’t until his uncle, the English department head at New York University, told him about industrial design programs in the Northeast that Cargill saw an opportunity to leave his medical studies behind. He applied to Pratt Institute in New York, was accepted, and transferred in 1948 to begin his studies in industrial design. The program provided an avenue for Cargill to combine his love for making things with practical applications, but pursuing fine art as a serious career path still hadn’t crossed his mind. “As far as doing art, I probably never would have done it if I hadn’t met Patty,” he says. “Because she was an artist all the way.”

Cargill met Patty when she was studying painting at Pratt. The two fell in love right away and married in 1950. He earned his B.A. in industrial design from Pratt in 1952, and then the two moved back to Beaumont. “They had just the start of the museum, and we thought we could have some classes,” he says, referring to the Art Museum of Southeast Texas. Initially known as the Beaumont Art Museum, it was incorporated in 1950. Cargill had his first southeast Texas art show there in 1951, and in addition to teaching at the museum, he and Patty cobbled together a living doing whatever they could. “We tried everything to begin with. Did a little advertising, all kinds of stuff. But there wasn’t really an art community.”

Hoping to become a professor, Cargill enrolled in the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, a self-directed graduate program that is often cited as one of the nation’s leading art schools. Patty stayed in Beaumont, making her own way and meeting up with two other women in the area who were involved with the arts. “While I was [at Cranbrook],” David says, “they cooked up the plot of everybody going to Europe.”

Cargill earned his M.F.A. in sculpture in 1954 and returned to Beaumont, only to be told he’d be leaving again soon to travel across Europe. “I wasn’t really keen on going at that time. I just wanted to come home and work,” he says, but his consternation was short-lived. “I got over that. It took me about until we got past Bolivar on the ship.” David, Patty, and their two friends took off on a freight ship across the Atlantic and embarked on a journey to and across Europe, venturing to France, Spain, and Italy. Cargill took photos of every sculpture he saw along the way. “We’d just gotten a new station wagon, and we took it with us,” he says. “We toodled around. We had no reservations. We went wherever.”

But their plans changed. “We were due to spend a year, but it turned out Patty was pregnant,” Cargill says. “So, we felt like we needed to come home.” They returned to Beaumont in 1956, where Cargill commenced building his home studio and settled permanently to raise his family and continue his work.

“We didn’t have air-conditioning until long after I was grown up,” chuckles Cargill’s daughter Idakatherine, now Idakatherine Graver, a painter based in Phoenix. She and her younger sister Chancel, a retired doctor, spent their childhoods in the fifties and sixties surrounded by their parents’ art—an anomaly within an industrial city. “At that time, in Beaumont, we were extremely odd,” she says. “I was very shy, and it was hard to be living completely different from everyone that we saw. I never knew there were times when we didn’t have money. I just thought my parents were so strange in the choices they made.”

And yet growing up in an artistic home had its own enchantments. “It was a tremendous space for imagination and experiencing the mystery of what it is to be alive,” she says. When the children were bored, for instance, David and Patty would set up a still life and have their children do contour drawings. “I think the life they created just soaked inside of me, and it’s really who I am,” Idakatherine adds. The Cargills’ creativity was unique in that it wasn’t built on trying to grab the attention of others. Instead, it was rooted in the mere pleasure of having worked hard to create something beautiful. “He did a lot of commissions to feed us, but also he was constantly doing his own thing,” she says. “I’ve never met anybody as unaffected by the culture and the need to either have a kind of status or security or do anything anybody else was doing.”

Whether he noticed what was going on in the culture or not, the culture started to notice Cargill. At some point in the seventies, his work drew the attention of Lincoln Kirstein, the arts magnate who, among his many significant contributions to American art in the twentieth century, is best known for bringing the Russian ballet dancer and choreographer George Balanchine to the United States. Together, they cofounded both the School of American Ballet and New York City Ballet.

Cargill and Kirstein eventually struck up a brief correspondence. In one of their letters, Kirstein described Cargill as “one of those rare creatures, a working-artist whose work corresponds to some necessity, and neither to vanity, self-exploitation or the haphazard corruption of the art-mart.” In the midst of their communication, Cargill sent catalog of some of his sculptures to Kirstein. At the time, Kirstein was a partner in a gallery in New York, and he invited Cargill to show his work there. The infrastructure for vocational artists in New York City was, like now, gargantuan compared with the handful of opportunities available in southeast Texas, and Cargill’s reputation might have expanded tenfold.

But Cargill turned him down. “Ultimately, I wasn’t prepared to do it,” he says. “It was very shortsighted of me. If you look at a career and everything, it was probably the dumbest thing you could have done.” Cargill attributes this lapse in judgment to the fact that he didn’t know who Kirstein was, and didn’t bother to investigate, either. “It was crazy,” he says. “Just crazy.” Instead, Cargill focused on becoming part of the southeast Texas art community’s fabric, and of the area’s landscape, too.

Many of the initial commissions David and Patty worked on after they returned from their European expedition in the late fifties came from local churches, beginning with St. Elizabeth Catholic Church in Port Neches in 1957. “Patty was teaching art lessons to little kids. One of their fathers was an architect from St. Elizabeth’s and thought there might be some sculptural project that I could do.” Through that connection, Cargill met with the church’s priest, Patrick Hickey, who commissioned Cargill to create the altar and the large-scale crucifix that hangs on the front exterior. It was a collaborative project with Patty, who designed the church’s stained-glass windows.

From there, Cargill started to build a rich assortment of liturgical art that can be seen at dozens of places of worship around the Golden Triangle—the area around Beaumont, Port Arthur, and Orange. In Beaumont alone, Cargill’s sculptures adorn the grounds of seven churches, and range from terra-cotta reliefs of children dancing around a Christlike figure to large, wooden entryways engraved with scenes of celebration. For the most part, his liturgical work strays away from realism and toward the abstract, stripping scriptural stories of their visceral qualities in favor of portraying more essential narratives of love, community, and joy. The ubiquity of Cargill’s work throughout churches in southeast Texas indicates that he can skillfully imbue sacred spaces with a sense of the divine.

Still, Cargill says the work simply paid the bills, and he’s hesitant to call himself religious. “I don’t know how to define that term. Do I have faith? Yeah, I got faith,” he says. But he doesn’t like to pin himself down to one particular denomination. “I was raised in the Presbyterian church, and I knew the rules. But it never got to my heart.” Regardless, Cargill’s work in southeast Texas churches led to perhaps his biggest liturgical commission yet: for the remarkable Chapel of St. Basil at the University of St. Thomas in Houston. Completed in 1997, the chapel is a white cube with a golden dome on top, a black plane that slices through the structure, and an entranceway designed like a tent flap. Inside is a stark, minimal space, where light pours in from outside and drifts across the room as the day ticks on.

Philip Johnson designed the building, and during its construction a committee of professors in sought out a local artist to contribute to parts of the chapel. Ultimately, they thought Cargill was the best and only choice for the job. “Many people don’t realize that a lot of the influences Philip Johnson had were medieval architecture,” says Charles Stewart, an associate professor of art history at the University of St. Thomas. “So he upgrades or modifies medieval aesthetic for modernist architecture, and, in a way, David Cargill does the same thing with sculpture: he takes medieval aesthetics and medieval ideas and modifies that for modern contemporary sculpture. So there was a nice fit between the architecture and the sculptures within the chapel.”

Cargill designed many of the interior elements at the Chapel of St. Basil, including the altar, the sculpture of Mary and Jesus in the chapel’s eastern wall, the tabernacle, and the Stations of the Cross. The latter is one of the church’s more striking features: it’s a “sunken relief,” where the sculptures are carved into the wall as opposed to jutting out from it. Light from outside fills the fourteen sculptures detailing Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection that comprise the Stations of the Cross, creating a near-holographic effect as the images appear to emerge from the wall and move as you walk by. “As the sun moves across the sky from morning to night, the patterns change within the chapel,” says Stewart. “So every time you go the chapel, it’s a different experience because the light has changed. If the chapel is also recording the passage of time, these sculptures and these Stations also record the passage of time.”

In 1998, Cargill received the national Religious Art and Architecture Design Award from the American Institute of Architects. But in true David Cargill fashion, the sculptor didn’t attend the flashy subsequent award ceremony in San Antonio. “I fluffed it off,” Cargill sighs. “It would take a couple of days of your time, and it would have been a little bit different if it was down the street.”

“If you are an artist in a community like this, such as David or myself, you can get a lot of work done because there’s not a whole lot of distractions like, shall we say, other larger communities or venues,” says Keith Carter, a renowned photographer who lives and works in Beaumont. “Unlike a lot of artists, whether they’re in New York or Beaumont, David never, as far as I can tell, was absorbed with being famous or having great note in art history books. He was always interested in doing work, and always was and is to this day generous to younger artists.”

Carter experienced that generosity firsthand when he was young. Before they built their permanent home, David and Patty lived in the garage apartment in the duplex Keith and his mother lived in. As a child, Keith would see Cargill working on sculptures in the garage and wander in. “I would stick my head in and say hello, and he was just the nicest man on the face of the earth,” he said. “We’ve stayed friends ever since.” As Keith grew older and developed his skills with a camera, he turned to David for mentorship. “He would lay my little, crummy pictures on the studio floor, and he’d crop them and recompose them. He would tell me things like, ‘you need to learn to be ruthless with space.’” Carter says. “And to this day, I’ve got that tattooed on my brain.”

In addition to his photographic work, Carter teaches at Lamar University, and he often takes students to learn from his old mentor. “I take my classes over there, if they’re a good class, once a semester, just so they can see how somebody lives with art and makes it and lives with it,” he says. “He makes quite a difference here.”

Cargill also serves on the acquisition committee at the Art Museum of Southeast Texas, advocating for artists who, like him, got their start outside of the traditional gallery system. “A lot of times, when someone wants to offer something, whether it be a gift or they want the museum to purchase it, a lot of people on the committee will look at that person, see their track record and say, ‘Well, where else have they had their work? Do they have work in any galleries? Do they have work in any museums?’” Kiel tells me. “But David will say, ‘Well, you got to start somewhere, and if you really like this piece, why hold back just because they’re not in any gallery or in any museums yet? Let’s be the first museum to take a chance and get the ball rolling.’”

Rooting himself in Beaumont also gave Cargill the space to nurture his family. “He stayed close to where he grew up, and we have a small family, but we’re close,” Idakatherine says. “And [David and Patty] had a really powerful, beautiful marriage, where they cared about each other the whole way.” Theirs was a lifelong partnership in art and love, and living with another artist only strengthened each of the works David and Patty did. When they weren’t working on commissions together, they gave each other constant feedback on their respective projects. “The initial idea [for a project] could come from her that I ended up doing, and vice versa,” Cargill remembers. “She was my harshest critic. Never hurt, though. Never hurt the end product.”

Cargill rarely strayed far from his family, but sometimes his art did draw him away. In 1962, Cargill spent nearly two months casting his commissions at the Guastini Foundry in Florence, Italy. Patty stayed behind to watch over the family. Cargill returned home energized and soon built a foundry of his own in his backyard. It was an unusual choice for Beaumont in the sixties, but to Cargill it was something that simply had to be done to continue his work. “It was primitive,” he says. “You just had to figure out a way to melt the metal and move things.”

“It wasn’t really fair,” Idakatherine interjects.

“There’s nothing fair about me,” Cargill says.

“Well, [my father] got to go to Europe while she stayed home. She would’ve liked to go to Europe while [David] stayed home, but it just wasn’t part of the time. It wasn’t the way people thought,” she says. “Especially here, where pretty much everyone I grew up knowing and she knew worked at home, and there just wasn’t any structure for her here to find her footing, really. I guess I just really feel for her. So I always like telling her story.” Cargill nods. “Yeah, I got credit for a lot her thinking.”

Despite these external pressures, David and Patty always found refuge in each other. “Art was the most important language that they shared and worked on,” Idakatherine adds. “She was always making things better.” The two of them were constantly collecting, thinking about, and creating art, and, naturally, their artistic processes became profoundly intertwined—which is particularly evident at a Dishman Art Museum show they collaborated on together in 2011.

Entitled “He Said/She Said: They Spoke with One Voice, Figurative Works by David and Patty Cargill,” the idea behind the exhibit involved having David choose one of Patty’s paintings, while Patty picked out one of his sculptures. The two works were then paired, resulting in, say, a sculpture standing on a pedestal in conversation with a painting on the wall right behind it. They followed this process to select all the pairs, exhibiting the best of both practices. “There was this implied narrative dialogue that I had never seen before,” says Carter, who took his students to see the show. “It was a beautiful experience.”

Patty passed away a year later, in 2012, after a decade-long battle with multiple myeloma. As her health declined, she stopped making art. Despite this, “she never stopped thinking,” David says. “No, she never stopped being an artist,” Idakatherine agrees. “It was wonderful to work with her,” David adds.

While “Life Is a Long Way” could be seen as the culmination of an artist’s career, it’s clear that Cargill still has many projects he’s set out to complete. He’s planning another solo show with the Art Museum of Southeast Texas in 2021 and hoping to bring another one of his recent creations to life: a sculpture of a man, waist-deep in rushing floodwaters, towing a woman, her two children, and a dog in the fragile skiff behind him. Cargill showed me the model, called The Rescue—says he was inspired to create the piece after seeing the civilian rescue efforts of the “Cajun Navy” after Hurricane Harvey devastated the area. And this spring, he will be honored as the featured artist at Lamar University’s Le Grand Bal, their annual fundraiser for the College of Fine Arts and Communication.

“My nature has never been to look back,” Cargill says. “It’s caused me lots of trouble in life because I need to look forward. I wake up in the morning and say, ‘Well, it’s a good day. Let’s do something.’ I don’t think I planned very well or anything, but I was happy doing what I was doing, and every day was a fresh day. I didn’t have to look to look back.”

“You’ve had a wonderful life,” Idakatherine says. David shrugs. “I can’t complain.”