When Delita Martin was a child, she used to place mirrors underneath her face and, as she puts it, “walk around the world upside down.” Mirrors, like the ones she tucked under her chin, were a portal to transport her into other realities. The Texas native has always imagined new worlds, but it’s only in the last decade or so that her imagination has merged with her spiritual beliefs to create the kind of art Martin displays in her newest exhibition, “Conjure,” which runs from March 13 to May 23 at the Art Museum of Southeast Texas.

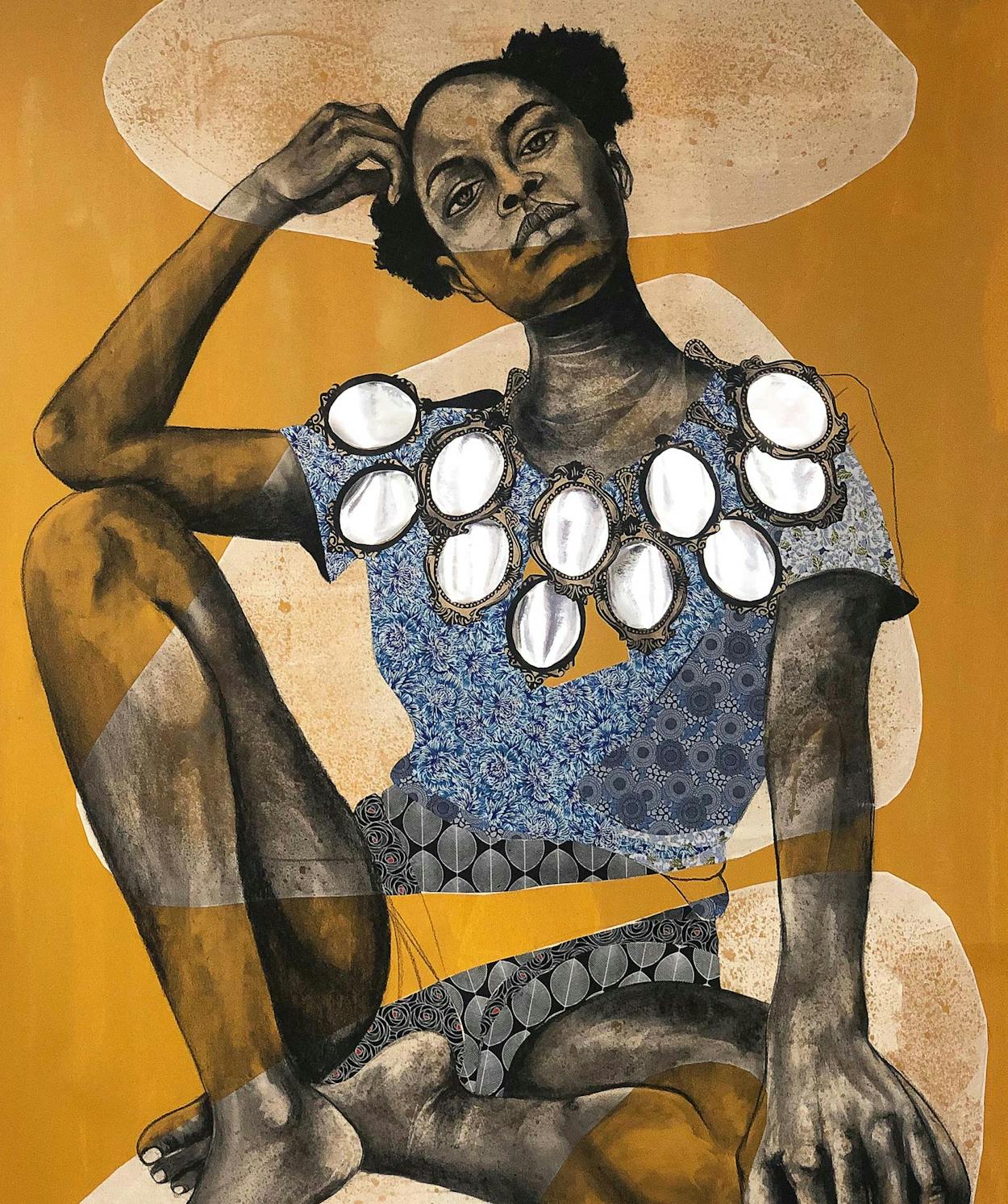

One work on display, Mirror Mirror, features a Black woman sitting against an orange background with her head cocked to the side and resting on her hand, with the elbow propped up on her knee. Her gaze is direct and unwavering, even as large white orbs cross over her face and body, revealing intricate prints and patterns in the areas they touch. One white patch is painted over her neck; through it, you can see that the neck is adorned with small mirrors. The mirrors are made of reflective paper, Martin says, so that as you meet the confrontational gaze of the woman in the painting, you’ll also behold yourself looking at her.

Those floating white patches in Mirror Mirror represent the realm Martin describes as the “veilscape,” which she defines as the “spiritual footprint that we leave in spaces wherever we go.” It’s that strange sensation you get when a new place somehow seems familiar, or when an empty space feels charged with energy. In her portraits of Black women, which are often mixed-media, Martin uses both painted patterns and patterned paper to make the invisible plane visible. She combines the veilscape with the physical realm using a mixture of charcoal, acrylic paint, gold and silver leaf, and a method of sewing called “tacking” that her grandmother taught her.

Martin’s maternal grandmother, Texanna Williams, is perhaps one of the biggest influences in Martin’s art. Williams lived with Martin’s large family (Martin is the youngest of nine) in their home in Conroe, Texas. The two shared a bedroom until Martin was thirteen, and the artidst traces many of her artistic inspirations and explorations back to intimate moments with her grandmother during childhood. In their bedroom, Williams would collect items like watches, perfume bottles, buttons, and scraps of fabric in jars and Folgers coffee cans that she kept on her dresser. By showing them to her granddaughter, Williams introduced Martin to the storytelling power of objects. “Every once in a while, she’d pour them out on the bed and she would go through and tell me stories about each little piece,” Martin says. “At an early age, I began to associate objects with people, places, and things.”

Now the domestic objects that show up in Martin’s work are rich with meaning. Jars and bowls, reminiscent of the jars her grandmother used to keep, represent the womb or the ability to hold and protect. Birds, which her grandmother loved, signify the human spirit. Each object conjures or calls upon a certain space and energy defined by love.

In one of Martin’s works, Trinity, three Black women gather closely. The piece is painted in blue hues, shot through with dashes of red and yellow patterns, and filled with more symbols that hold weight for Martin: hoop earrings that represent infinity and timelessness, stools that represent leadership, and a bird, or a spirit, encased in its own distinct blue pattern. One woman has her back turned to the viewer, and although the other two are facing outward, the mood of the piece suggests that we’ve intruded on an intimate moment between them. In a statement about the work, Martin describes that moment as “a sacred meeting between women in a spiritual realm.”

“Conjure”—which features twenty larger-than-life portraits of Black women exploring the veilscape, as well as Martin’s 2016 “Plate Installation,” which is her take on Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party”—captures the spirituality with which Martin approaches her artwork. She treats her studio in Huffman, northeast of Houston, as a sacred space and is protective of it, only enlisting the help of studio assistants on a project basis. Martin also never sketches out her ideas. She finds inspiration everywhere, even in the pattern of a stranger’s shirt at the grocery store, but she doesn’t start any work with a plan. Instead, she waits, acting as a vessel and allowing a piece to reveal itself to her, layer by layer. “There have been times when I’ve had work up and I’ve just set it to the side because she hasn’t told me who she is,” Martin says. “She hasn’t told me what her story is.”

The mystical approach is a relatively new one for Martin, although she’s considered herself an artist all her life. Her father (who made oil paintings in his free time) and her mother (who would regularly introduce Martin by saying, “This is my baby child and she’s an artist”) encouraged her craft by calling her an artist from age five—and letting her draw on everything. One of Martin’s first creations is what looks like a Christmas tree, drawn on the back of an oil painting of a white Jesus that her father made.

Because her father studied at Texas Southern University, a historically Black university in Houston, Martin, a self-proclaimed “daddy’s girl,” set her heart on attending the same school. She earned a fine-arts degree from TSU with a concentration in drawing in 2002. She later met her husband and the two moved to Indiana, where she pursued a graduate degree in printmaking at Purdue University, earning her master of fine arts in 2009 while also teaching art. After she graduated, Martin continued to teach while making art and exhibiting her work on the side, until finally, in 2013, she committed to being a full-time artist and established her studio Black Box Press. In 2016, she built a physical studio space, a 1,700-square-foot building in Huffman, where she now lives with her husband and son.

At TSU, Martin began the practice of putting together her portfolio, which gave her an opportunity to figure out the common thread that ran through her work. In graduate school, it finally struck her that her subjects were all African American women, and that everyday objects such as jars kept making reappearances. “‘What is the importance of these portraits? What are they saying?’” Martin says she asked herself. “I ultimately realized that it was a search for identity. At its very core, my work is very much about identity and reconstructing that identity of African American women and myself.”

Martin’s paintings are a rejection of the stereotypes and unrealistic beauty standards often projected onto Black women, who are repeatedly rendered invisible or hyper-visible in media. Martin was raised Baptist (hence her father’s painting of a white Jesus), but as she got older, she found herself questioning her religious upbringing and exploring the teachings of West African religions. From this perspective, memories of her grandmother’s rituals took on new meaning. Williams would interpret dreams and use herbs to heal, practices Martin’s Baptist upbringing frowned upon. Now Martin believes in a higher power, although it’s not necessarily the one she was raised to believe in.

“In a way I’m still searching, and this is the journey that I’m on,” Martin says. “That journey plays out in my work, and so I’ve become very interested in how I look when I become the spiritual.”

There’s a shift in energy, both physical and metaphysical, that Martin creates when she fills a space with larger-than-life portraits of Black women. In “Conjure,” Black women are the center of attention. But even as they invite our gaze, the women in Martin’s artwork are also looking back at us, sometimes, reflecting us back to ourselves. “You’re in a room with 21 of these women and they’re looking at you,” Martin says. “So, are you the viewer? Are you now being viewed?”