This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It’s opening night for the new G. Harvey Show, and the nouveau riche of the New West have gathered to celebrate their heritage. At the Trailside Galleries in Scottsdale, Arizona, the last great bastion of traditional Western art in a world gone abstract, sleekly dressed couples mill about, holding slim, elegant drinks that look like urine specimens, looking other couples up and down as if they were paintings. Men are in bolos and Lauren, their year-long tans bringing out the color in their eyes. Women glide by in suede skirts held up by belts with silver buckles, their neck muscles tight from the exercise that comes from wearing enormous turquoise earrings.

They all have the bearing of people who are obviously important, wherever they are from. And they have flown in from more than a dozen states, including California, Colorado, Minnesota, Montana, Wisconsin, and of course Texas. Gossip abounds that even Europeans are in the crowd. Look, in the corner, there’s Pete Folger, the senior vice president of the ad agency Saatchi and Saatchi in Los Angeles, talking to a man who is referred to as “a major Seattle investor.” And in a huge gray cowboy hat comes the strapping Roger Craig, the manager of the San Francisco Giants. Shaking hands all around is the stately Kendrik deKoning, a commercial and residential builder in Phoenix. Rich as chocolate, the gallerygoers’ lives are seemingly perfect—except for one vital matter. They are all missing the very thing that can make them truly stand out and turn their wealth into status. They all need a painting from a reclusive 56-year-old Texan who signs his name “G. Harvey.”

The bluebonnet genre was dying, and Harvey knew it: “I just wanted to try something a little different and do something dramatic with a cowboy.”

Gerald Harvey Jones might never turn a head among the East Coast art establishment—one director of a respected museum of American art dismisses him as a postcard painter—but to those who follow Western art, where the landscapes are grand, the Indians noble, and the cowboys stoic, he is like a god. He turns the brutal world of the Old West into a kind of romantic Eden, a land where no one is hurting and opportunity can be found at the end of every journey.

No other Western artist produces so many paintings—about fifty a year—at such high prices. One of his large works will easily fetch $70,000. But what’s amazing is how he has done it. Over and over, whether the setting is in the wilderness or a quiet Western town, Harvey tends to paint the same subject: a cowboy on horseback, headed down the middle of the painting toward an unknown future, with the last streaks of the setting sun or soft window lights from buildings helping to guide his way. This simple image, the horse and rider at twilight, has a mesmerizing power over his followers.

“My God, there it is,” says one Harvey worshiper as she comes through the door in one of those designer sweaters with little patches of fur sewn into the shoulders. Other fans beside her murmur in uncritical delight. The centerpiece work on the front wall, on sale for $75,000, is Cowboy’s Payday, a three-by-five-foot painting of a group of cowboys at dusk herding Longhorn cattle to market down a rain-drenched street. As in all of Harvey’s paintings, the cowboys are silent and sinewy, the faces are never clearly seen, and a suffused light, emanating from a saloon and a church at the sides of the painting, bounces off the watery ruts in the road. “My dear,” says the Trailside Galleries’ president, Christine Mollring, an austere British woman with clipped black hair like a Chanel model, “everyone is going to want that one.” Mollring looks like the last person to run a Western art gallery—in fact, she didn’t know that cowboy art existed when she bought Trailside in the early sixties—but she definitely knows how to sell. “This is vintage Harvey, you know,” she says confidentially to a potential buyer, referring to Cowboy’s Payday. “There’s no telling what it will be worth someday.”

Her customer, a broad-shouldered fellow in a leather duster and ostrich boots, turns away from Mollring. “Well, where is he?” he asks, as if the sight of Harvey might in some way validate this vision of the West. His gaze drifts over the hundred or so people in their de rigueur Western fashions, staring at art that has nothing to do with the way they live now. He skips right past a thin man in a plain gray suit with a red rose in the lapel. The thin man’s gray eyes blink behind his glasses, and his white hair, cut the same way for the last ten years, is flipped up in front. Standing beside his prim, pretty wife, nervously interlocking his fingers before him, he smiles weakly.

This is G. Harvey, the painter of the great American cowboy? Artist of the golden West? In Western art, the painters are as beloved for their masculine cowboy lifestyles as for their work: Arizona cowboy painter Bill Owen lost an eye last year in a calf-roping accident, but the demand for his art remained steady even though he was painting one-eyed. But Harvey? He looks like a slimmed-down version of Larry “Bud” Melman from David Letterman’s show.

Those who recognize Harvey come up reverentially to shake his hand. “On my ranch,” says one man, “I’ve probably got every print you’ve ever done.” A woman exclaims, “I bought one of your paintings years ago. It was of a horse in front of another horse. You remember that one?”

Harvey smiles as politely as he can. “He sort of is uncomfortable about publicity,” a gallery representative whispers. Actually, Harvey is so adamant about his privacy that back in his Hill Country home in Fredericksburg, he has built a high stucco wall around the yard and his studio to keep the public from looking in. “I don’t enjoy going to these shows,” he says in his soft, flat voice. “If you want to know the truth, I’d rather be home painting.”

After murmuring thank-yous to everyone, Harvey quietly stands back in a corner as all but one of his 32 works, ranging in price from $3,600 to $85,000, are sold.

Dozens of people have put slips of paper in envelopes beside each painting; whoever has his name drawn from the envelope gets to buy that work. “Dammit, Sid,” says the builder deKoning, “draw my name.” DeKoning has bid for seven of the works, from cowboy paintings to landscapes to city scenes, but as the sale winds down, he realizes grimly that he won’t get one. The gallery, however, brings in $700,000 for the night.

“I’ve waited years for a moment like this,” says the “major Seattle investor,” visibly moved, when he hears his name announced for Cowboy’s Payday.

But the paintings are only half the story. The other half, of course, is money. As the Harvey lovers drift away, they never realize that they have been part of a carefully orchestrated plan to turn the shy artist into a highly desirable yet elusive commodity worth millions of dollars on the art market. In a financial and marketing scheme that experts say is unheard of in contemporary art, Harvey has signed a multimillion-dollar contract to sell his art exclusively to a wily and widely respected Houston entrepreneur named Randy Best. Through the purchase of art galleries and art printing companies, and with ingenious promotional techniques, Best, a longtime Western-art lover, has essentially put Harvey “into play,” hoping to turn him into one of the most popular artists in America, regardless of what the critics might say. The Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History is negotiating with Harvey to have him paint a series to be exhibited as part of the five hundredth anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of the New World. And he is preparing a whole new series of paintings to show in Leningrad and Moscow—maybe at the Kremlin—in either 1992 or 1993.

As surprising as it might be that a man whom some consider to be just another cowboy artist could gain such attention, G. Harvey’s fame is a powerful reminder of the way America’s frontier heritage still grabs hold of our collective memory. But his story is also a modern version of how the West has always been won—by making something new out of virgin territory and by using a little imagination to become richer than one’s wildest dreams. “Gerald wants something we all want,” says Tony Altermann, an influential art dealer from Dallas and a longtime Harvey friend. “He wants something of his to last beyond his lifetime. He is searching, in his way, for immortality.”

If there is anything that seems destined not to last, it is Western art. Long the butt of jokes by connoisseurs of modern and European art, always relegated to a provincial, second-class status in art centers like New York, the head-’em-off-at-the-pass school of painting—with its fat buffalo, windswept prairies, Indians riding furiously, and explorers shooting rifles—gets hardly more than a mention in American art history textbooks.

But, oh, does it sell. As far back as the early 1800’s, painters and illustrators headed west to record the last frontier, and when they returned, they found a stream of curious buyers ready, regardless of how much the art snoots hated it. In the mid-1860’s, Albert Bierstadt sold a sixty-square-foot painting of the Rocky Mountains for $25,000 to an American railroad man living in London.

Then, in the 1880’s, two commercial illustrators, working for publications such as Harper’s Weekly and Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly (the nineteenth-century equivalents of People magazine), hit upon the formula that helped transform the West into the stuff of myth. Frederic Remington and Charles Russell revolutionized the Western art business by making a folk hero out of the great white man on horseback. Their cowboys and cavalry troops portrayed good over evil, intrepid men who courageously beat back savage Indians and a savage land.

Harvey lovers never realize that they are part of a carefully orchestrated plan to turn the shy artist into a highly desirable yet very elusive commodity.

Though one elitist at the time sniffed about Remington’s “indifference to beauty of form, his unfeeling realism, and his poverty of color”—a critique that can still be applied to much Western art today—his and Russell’s works were eagerly sought after by industrialists, bankers, and other rich people who previously thought of American art as portraits of ugly rich Easterners and their uglier daughters. This new cowboy art reflected their own lives with its portrayal of hard, self-reliant men ready to confront all odds in their drive for success. Russell got $10,000 for his large works in the early 1900’s, which was the auction price of a Monet at the time. Remington’s Bronco Buster became one of the most famous nineteenth-century American sculptures. Even today, their work sells for stupendous sums: Remington’s Coming Through the Rye, a sculpture of four cowboys riding abreast, sold at auction last year for $4.4 million. In the Depression years, oilmen like Tom Gilcrease of Tulsa and Amon Carter of Fort Worth began picking up as many Russells and Remingtons as they could. Gilcrease and Carter eventually opened their own museums—and for the next thirty years, that is where Western art stood. A small group of oilmen competed for the next Remington that came up for sale while everyone else turned to John Wayne movies and Louis L’Amour novels for their frontier mythology. Though the Western masters were selling, the contemporary Western artists were not. In 1965 four cowboy painters got together in an Arizona bar and formed the Cowboy artists of America, dedicated to preserving the Remington and Russell tradition—they struggled to find buyers for their paintings.

Still, there were a few holdouts who were certain a market existed somewhere for contemporary Western art. In 1966 a cigar-chewing former Texas Tech football player named Bill Burford, who knew little about Western art, opened the Texas Art Gallery in downtown Dallas, where he tried to interest rich Texans in mostly bluebonnet paintings by artists like Porfirio Salinas. “Hell,” says the burly, balding Burford, ”we were just muddling along, looking for someone who could paint a good Texas scene. Back then, you know, this state had bluebonnet painters coming out its ass.”

One of those painters was a skinny young San Antonio native who, in the sixties, was supervising the arts and crafts center at the University of Texas at Austin. At night, Gerald Harvey Jones would work on typical Hill Country landscape paintings, with the big sky, the burnt orange hills, and the bluebonnets scattered in the lower front of the canvas. He shortened his first name to an initial and dropped his last name to make it easier for buyers to remember him. But it didn’t help. Harvey sold paintings to galleries for as little as $25 apiece.

His break came in 1965, when John Connally, the governor of Texas and an early Western art collector, came across the young Harvey’s work in an Austin gallery. Needing presents to give to various Mexican governors on an upcoming trip, Connally hired Harvey to paint twelve views of the Connally ranch. “I knew he had a great future,” Connally recalls, “but the reason I liked him was that I could afford him.” Connally also showed Harvey’s work to his buddy Lyndon Johnson, then the president of the United States. Johnson promptly commissioned Harvey to paint Johnson’s birthplace, boyhood home, and ranch house. Harvey had learned his first lesson in selling art: If certain famous people buy your work, then other famous people will want it too. “All of a sudden,” says Harvey, ”I thought I had a future doing this.”

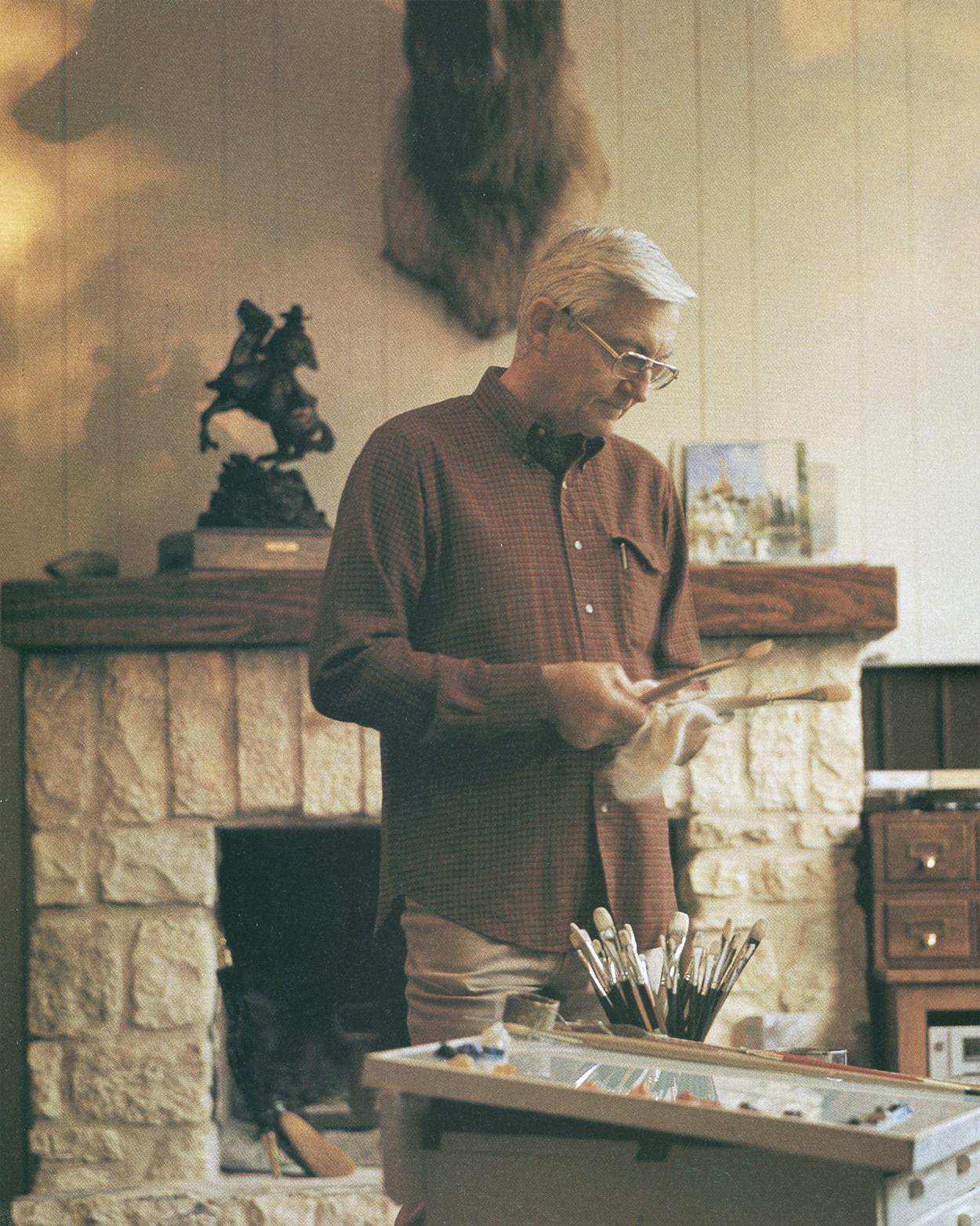

Harvey recalls his past for me one morning in the two-story studio that sits fifty yards behind his 137-year-old Fredericksburg home. Sunlight slips through the windows, past walls full of Western paintings, deer and antelope heads, and bear and cougar skins. A Bach Brandenburg concerto plays lightly from the upstairs stereo. Harvey, in white New Balance tennis shoes, khakis, and a white button-down shirt, slouches on a couch, a man utterly at ease compared with the way he looked at the gallery opening. Though art historians’ surveys never include a Harvey painting in their lists of the most prominent Texas art—the lists tend to prefer works like the half-buried Cadillacs in Amarillo—Harvey’s art is prominent in other ways. Six corporations have contacted him, each saying it would pay him at least $1 million for a series of new paintings.

Today, Harvey is himself a corporation. Trailside Galleries, which exclusively handles his original paintings, says it has two thousand people on its mailing list who are interested in purchasing his work. This year eight of his paintings will be turned into prints, selling in more than 1,300 galleries around the country for up to $1,000 each. And now, to spread his name in other parts of the country and Europe, Harvey has begun to paint non-Western scenes: He has finished at least three Civil War paintings to capitalize on the resurging public interest in that war, and he is in the midst of a project to paint turn-of-the-century street scenes of ten major cities in the U.S. Both the Civil War and the street-scene paintings will be turned into another highly advertised series of prints, bringing him thousands of new fans and untold thousands of more dollars.

Yet even these new works are basic variations of his trademark Western look. In two of the Civil War paintings, for example, Confederate and Union troops are headed through rain and snow on horseback. Change their uniforms and they could be cowboys. In a huge painting of an early 1900’s Wall Street scene that Harvey completed last year, a man in a yellow slicker and hat, looking suspiciously like a Texas cowboy, stands in the lower center of the canvas tending to a horse.

As Harvey talks, his eyes occasionally flit over to another just-completed painting, leaning against a wall, of five cowboys on horseback headed down a snow-packed road in a Wyoming valley. The Tetons loom behind them. The dying light of the afternoon slants across the painting, strengthening in the foreground and fading toward the back. He could do this kind of scene in his sleep. Yet when he puts it up for sale, somebody’s going to pay at least $60,000 without blinking an eye.

“You see this right here?” he says eagerly, pointing to the horses in the painting. “a horse’s ears set the whole tone of a painting. If a horse’s ears are relaxed, it gives a whole different feel to it than if the horse’s ears are back. I don’t find a painting very intriguing unless I can put a horse in it.”

To learn how to paint a horse, in 1967 Harvey bought an old mare named Buttons, kept her on a piece of land he owned near Austin, and went out daily to sketch her. He began taking trips to the Spade Ranch near San Angelo to sketch cowboys. Though the crew-cut, bespectacled Harvey didn’t even pretend to be a cowboy—he rarely rode a horse and had tried raising a few head of cattle—he knew the bluebonnet genre was dying. “I just wanted to try something a little different,” Harvey says, “and do something dramatic with a cowboy.”

Yet he refused to do the same old Remingtonesque picture of the cowboy hurtling through the brush with gun in hand. Harvey is a devout Christian with little stomach for violence, and he is a devoted family man who says proudly that he has consulted his wife, Pat, on every decision he has made, even artistic ones. He didn’t want to show guns at all. Compared with most Western painters, who liked to have their stagecoaches bouncing and horses bucking, Harvey decided to depict cowboys on horseback as they drifted through rainy towns, forded gentle rivers, or cut through fresh snow. His cowboys were going to be the last great independent men, painted a little taller than normal men and always heading someplace else.

“Frankly,” says Michael Duty, the director of Indianapolis’ Eiteljorg Museum of American Indian and Western art, “I thought his paintings looked like one of those CinemaScope movies shown on a regular television screen, in which all the figures got elongated—and for me, it all seemed a little too pat.”

Harvey, however, thought there was an audience for what he likes to call “nostalgic, wholesome themes.” He wanted to create a dreamy, serene West that was about to vanish forever, one heroic age yielding to another. In his Western city scenes, for example, his cowboys ride on the same roads with streetcars and Model T automobiles. In the background are oil derricks or the first tall buildings of downtown. Harvey has bathed the scenes in a twilight glow, adding gaslights, long shadows, warmly lit windows, and oil-field flares to enhance the atmosphere. ”I thought I needed to juice up the paintings,” says Harvey. “Add some mood.”

Indeed, Harvey found his work could touch the Western middlebrow audience in a way other paintings did not. And it came right at the perfect time—for just as he perfected his trademark cowboy look, the boom hit.

In the late seventies, as the price of oil headed past $30 a barrel, Texas entered one of its most wondrous periods of wretched excess. A lot of people found themselves rich and proud of it, ready to show off their splendor by purchasing something other than another home or airplane. And that’s why, on a March evening in 1976, four hundred of them dressed up in black ties and evening gowns and went to the ballroom of the Adolphus Hotel in Dallas to watch something called the Western Heritage Sale.

Joe Marchmann, a wealthy Plano land developer and part-time Santa Gertrudis breeder, and John Connally, who also raised Santa Gertrudis, had decided to promote the breed by auctioning 38 head of the cattle in a setting that resembled a glittery society ball. To add even more glamour, Connally suggested throwing in a few cowboy-and-Indian paintings to be auctioned off in between each cattle sale. “To be honest with you,” says Connally, ”we didn’t have a clue what would happen.”

What happened was the very rebirth of Western art. The crowd, with nothing but time and money on its hands, went absolutely gaga. The cattle auctioneer, selling paintings just like he would a bull, would shout. “All right, what am I bid for this Harvey? It’s a nice big old fine piece. Hum-de-la-hum-de-la, how about ten thousand dollars?”

“It was a little insane,” says Bud Adams, the owner of the Houston Oilers and now a huge Western art collector. “We didn’t know if the art was good or bad, we didn’t know the artists, but we were so caught up in the hoopla, trying to out-bid everyone there, that we would have bought any old cow painting.”

Each year, the prices, and the hype, got bigger. The Western Heritage Sale was moved to Houston’s Shamrock Hilton to accommodate larger crowds of nearly 1,500 people, and in 1981 $4 million worth of art was sold. Prices for a single painting were hitting six figures. “If we had told Connally that we’d sell more art by shooting the artist out of the cannon and landing him in a net across the ballroom, he’d do it,” says Don Hedgepeth, a Western art consultant from Kerrville who helped recruit the artists for the early shows.

The Texas boom for cowboy art also helped fuel the boom throughout the West: The annual show for the Cowboy Artists of America in Phoenix went from $320,000 in sales in 1975 to $1.4 million in 1980, mostly because Texans flew out there to buy everything in sight. In 1979 ARTnews magazine claimed that Western art had become “one of the highest-priced sectors in all American art,” and soon dozens of Eastern artists headed West, donning cowboy boots and hats, painting Dustin Hoffman–looking Indians and stereotypical cowboys riding oddly shaped Thoroughbreds.

Much of Western art is still laughably bad, no more than overblown imitations of a Remington or a Russell that the artist has seen in an art book. Even the titles are imitated. For example, in 1889 Remington painted Cow-boys Coming to Town for Christmas. In 1987 G. Harvey painted The Cowboys’ Christmas. As one newspaper art critic has written, contemporary Western art is “maybe a few steps above black-velvet Elvis paintings.”

But one man’s kitsch is another man’s beauty. A few painters scattered through the West did emerge as stars. Some painters became known for their Indians, others for their cavalry scenes, others for their great trail rides—and Harvey for his shadowy cowboys. Art dealer Burford staged a series of shows for Harvey through the late seventies, and the invitation list was like a who’s who of Texas power: Amarillo oilman Boone Pickens, Dallas mayor Robert Folsom, Kerrville flooring and pizza tycoon Lloyd Brinkman, and Dallas developers John Eulich and Mack Pogue. They were men who never lost sight of the idea that a good painting was a good-selling painting, a financial investment that could be sold for a profit later on. “Harvey became the status symbol of the new oil-money crowd,” says Marchmann, who co-founded the Western Heritage Sale. ”It seemed like there was this little club of men, all gunning for the next G. Harvey painting just so they could say they had beaten the others at getting it.”

There was even a Harvey auction at Burt Reynolds’ home in Los Angeles. The Harvey club flew out from Texas to mingle with Burt’s friends, like Sally Field, Dom DeLuise, and Ed McMahon. Another guest, comedian David Steinberg, called the auction “the greatest collection of gentile wealth ever assembled in one room.” In 1980 another Harvey auction at the Fairmont Hotel in Dallas, attended by eight hundred people, brought in just under $1 million in sales for 27 paintings and 10 bronze sculptures, which was said to be one of the largest sums ever collected by a single contemporary American artist in one show.

Harvey is still widely popular even though, as one Western art consultant remembers, “The pictures in the catalog for one Harvey show looked just like the pictures in the catalog for the next year’s Harvey show.” For those who followed Western art but weren’t Harvey lovers, it was a baffling phenomenon. What made Harvey so much more appealing than the other Western artists who were actually better painters and also painting a greater variety of subjects?

“They’re just nice to look at, plain and simple. There’s a good, nostalgic feeling about them you don’t see in other artists,” says Pickens, who has hung his sixteen Harvey paintings throughout the offices of his new Mesa Limited Partnership headquarters in downtown Dallas. But no doubt part of Pickens’ love for Harvey is revealed when he happily bounds around the office with an art appraisal list in his hand, pointing out that a Harvey that he bought in 1970 for $3,200 is now worth $25,000. “And look over there,” he exults. “You see this one, Boomtown Drifters. The best piece Harvey has ever done. We got it in 1979 for sixty-eight thousand dollars, and it’s now worth more than a hundred thousand dollars.”

Brinkman, who has nine Harvey paintings in his boardroom, is one of the biggest private collectors of Western art in the world. His corporate headquarters, filled with hundreds of paintings and sculptures, is better than many Western art museums. Yet despite his obvious aesthetic love for the subject, he never forgets that art is commerce. It was a lesson he passed on to Harvey, whom he befriended in the early seventies. Brinkman taught Harvey that an art career is built like a good business: One finds his niche in the market, creates a product that fills that niche, and never strays from it. Recalls Brinkman, “I said, ‘Hell, G., it doesn’t make a lot of sense to paint a regular painting for ten thousand dollars when you can put those lights in and knock up the price to thirty thousand.’ ”

But no one took greater interest in Harvey than Randy Best. The 47-year-old Best is well known in the Texas financial community for his agricultural, real estate, and oil-drilling investments as well as for the Mason-Best partnership that specializes in large corporate acquisitions. Ever since Best read a book as a young man about Charles Russell, however, his greatest passion has been Western art. In G. Harvey, he saw someone who could enchant a nation the way Remington and Russell once did, and he wanted a piece of the action.

In late 1984 Best came to see the artist and, using oil-field parlance, announced that he wanted to buy all of Harvey’s production. “Whatever you paint,” Best said, “I’ll write a check for it on the spot.” It was an astounding proposal. Best essentially became to Harvey what the fifteenth-century Medicis were to the Renaissance painters—his patron, his sole supporter, and his mentor. Best had a plan to spread G. Harvey’s name throughout the world.

If one only reads the New York art writers, it is easy to believe that the most significant art trends in America today involve multimillion-dollar Van Gogh sales at Christie’s or the “discovery” of the latest avant-garde artist in SoHo. But in the eighties, another movement began to emerge, especially in the West, emphasizing realistic, nonabstract American painting. Southwest Art, a magazine begun in Houston in 1971 to highlight cowboy art for Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma readers, now covers all representational art west of the Mississippi; with a circulation of 73,000, it has become one of the top three art magazines in the country. New museums focusing on American realism have opened in Indianapolis and Los Angeles. Scattered throughout the West are numerous “schools” of art—wildlife artists, Santa Fe landscape artists, Taos impressionists, Native American artists, California plein air artists, Arizona desert artists, Jackson Hole mountain artists, and of course, the cowboy artists. “We’re in for another set of increases in this marketplace,” says Jacqueline Pontello, an editor at Southwest Art, ”and the difference this time is it’s not going to be centered in Texas. It’s going to be national. I get calls every day from all over the country asking what big Western artists are hot.”

In 1985, though oil prices were dropping and many big-time Texas Western art buyers were going bankrupt—the whole Texas cowboy art market seemed on the verge of collapse—Randy Best also sensed a national boom on the horizon. Best told Harvey that he would sign a written contract to buy everything for the next decade. Harvey was jolted. “I didn’t know what to say,” Harvey recalls. “It was like a dream. I could now paint all I wanted, anything I wanted, and never have to worry about anything else.”

Rumors quickly circulated that the agreement was worth $13 million to Harvey over the next ten years. No one in the art community had ever heard of such a thing. It was like one of those contracts that free-agent baseball players received. How could Randy Best, rich as he was, afford to shell out that kind of money, considering the fickle taste of the public? What if no one cared about Harvey’s work in a couple of years?

Best won’t comment on the amount of the contract except to say that it was worth “many millions of dollars.” He explains, ”But the feeling was that Harvey was such a hot property that if you had some kind of deal with him that was even remotely reasonable, you would come out in the long run very well.”

Best was already experienced in this game. When he was thirty years old, he started representing a little-known landscape artist from Victoria named Dalhart Windberg. He tried all kinds of schemes to make Windberg famous. He once advertised that he would give away a Windberg print to anyone who would buy an American car or home by a certain date. All one had to do was walk into a designated gallery, receipt in hand, to pick up the print—whereupon the gallery owner would try to sell that person two or three more Windberg prints. “There was a time when you couldn’t go into a dentist’s office without seeing a Windberg print on the wall,” says one famous art critic. “It was obvious that Randy was one of the few people around who had an instinct for making money in art.”

With the Harvey deal, what few people knew was that Best had ingeniously set up a pipeline to pump Harvey’s work all over the country. He had quietly bought Trailside Galleries in Scottsdale (and its sister gallery in Jackson, Wyoming) and art galleries in Dallas and Houston in order to sell Harvey originals. He bought interest in Southwest Art magazine in part to advertise his star artist. And he set up contracts with art dealers around the country to handle Harvey prints that would be coming from—that’s right—Best’s own printing company, Somerset House. “What we soon realized was that Randy Best was out to corner the Western art market,” says Danny Medina, an art writer in Scottsdale. ”He could buy painters and package them. You weren’t going to be able to hide from someone like G. Harvey even if you tried.”

“Not true,” Best tells me one afternoon in his Dallas office, his steely blue eyes bearing in. Behind him is a large Harvey cowboy painting; three Harvey bronzes sit on various tables. “A plan like this is only as good as the artist, and Harvey is at a point where his wonderful reputation feeds upon itself. We just help speed along that reputation all over the world.”

According to the arrangement, Best and Harvey decide on a certain retail price that a painting will sell for at Trailside, and then Best pays him 60 percent of that price; the 40 percent Best makes when he sells the painting, he keeps as profit and to run the gallery (most galleries keep between a half and a third of the price they get for a painting). While other artists have to sell their work as soon as they finish it to make a living, Best has the luxury of keeping Harvey’s work off the market for as long as he wants. In Best’s hands, a Harvey painting is like a rare commodity, hoarded and manipulated to drive up the price. It creates a feeling of cliquishness about his work. People begin to wonder what Harvey is doing behind those walls of his home. By the time his highly promoted, once-a-year show comes around, Harvey lovers are chomping at the bit to get to his work.

And if they can’t get one of the originals, they can always get a print. To maintain Harvey’s image of exclusivity, Best offers limited editions of a Harvey painting, sometimes as few as 1,250 prints. Other times he offers prints as “time-limited,” meaning that a person has to buy that print before a certain date, at which point the prints will be forever taken off the market. Through careful marketing, Best has made it feel like an accomplishment just to get hold of a fairly cheap Harvey print.

So far, say Best and Harvey, the plan has worked perfectly. “How could the damn deal go wrong?” asks Bill Burford. “I’ll tell you this much. If Harvey’s not the most famous artist around, he’s the richest. He’s got to be making two million dollars a year now, because he was making a million dollars a year with me, and that was ten years ago.”

As evidenced by last spring’s Trailside sale, Harvey truly has a bigger national following: His 32 paintings sold to buyers from sixteen states, including Vermont and New York. And although Best has now sold his interests in Southwest Art and in the Dallas and Houston galleries—Harvey paintings have bypassed Texas altogether and are now sold only at Trailside—he has used his numerous contacts to get Harvey the Smithsonian deal (“a chance for enormous national exposure,” says Best) and the Russian tour, for which Harvey will paint scenes of Russia at the turn of the century. There is little doubt that those scenes will show a rider, bent slightly over his horse, trudging down a gloomy Moscow street.

And so all G. Harvey must do is produce—a challenge that does not seem particularly difficult, considering how driven he is. Each morning at six o’clock he walks out the back door of his home filled with his own paintings and heads for his studio, where he will paint, save for a breakfast and lunch break with his wife, until six o’clock that evening. Though Harvey has his temperamental side—“He’s a total prima donna about his work,” says one art writer, “just like, well, any other artist”—he is genuinely pleasant to be around. Walking down the main street of Fredericksburg, he is unassuming, waving almost shyly at the shopkeepers he knows, and at a little cafe, gently inquiring of a waitress if she’s having a nice day.

It is a placid life, but I still cannot help but wonder if he gets tired of it, especially the painting. “Think about it,” says Burford. ”He’s had so much pressure on him to paint, to fulfill all those obligations, that he’s got to be like a machine.” At lunch, I ask Harvey if he ever gets bored doing all those cowboy-on-the-road paintings.

“Sometimes I might get a little tired of it,” he says, “but then I always go back to it.”

I remember something Boone Pickens had once told me: “Never forget, Gerald gets a lot of pleasure out of what he does, but he’s also a businessman. He knows he’s got a technique that sells. It’s like a guy with a golf swing. Why fool around with the swing if you’re playing excellent golf?”

I ask Harvey, “Do you go back to that kind of painting because that’s what people want?”

He is silent for a long time. “No,” he says in his same flat voice. “It’s hard to explain. There’s just something about it that intrigues me, that always has. Something about the nostalgia, about all those people back then, about the way families worked, about how the light coming out of those windows felt so warm, so kind. . . . I don’t know.”

Lunch is over, and we head back to the studio. I want to tell him that I think his paintings ignore how difficult the West really was. Hardship was the rule back then; life was brutal and short. He is painting an illusion. But then he stops and looks at me, and suddenly full of emotion, he says, “You have to realize that these paintings are all I’ve ever wanted to do. It makes me happy. Even if no one bought them, I’d do them. And the amazing thing to me is that people get the same kind of satisfaction out of them that I do.”

For Harvey, I realize, the West remains a paradise of the imagination. Its history did not create myths for him so much as his own myths created the West. Perhaps that’s why he keeps constantly painting these same scenes, to remind himself that those myths will never go away. And in the end, what’s wrong with that?

Back at the studio, the conversation winds down and Harvey is fidgeting on the couch. It’s obvious that he’s ready to go back upstairs, where another painting waits for him on the easel. “I’m just getting started, and I’m trying to get just the right slant of light,” he says.

I shake his hand good-bye, he pats me on the shoulder, and I walk outside toward the high stucco walls that guard his home. But before opening the gate, I hear the sound of Bach swelling from the studio. I turn back once more to look. The artist is already at work again, a wistful chronicler of a disappearing, twilit world.

- More About:

- Business

- Art

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Cowboys

- Skip Hollandsworth

- Fredericksburg