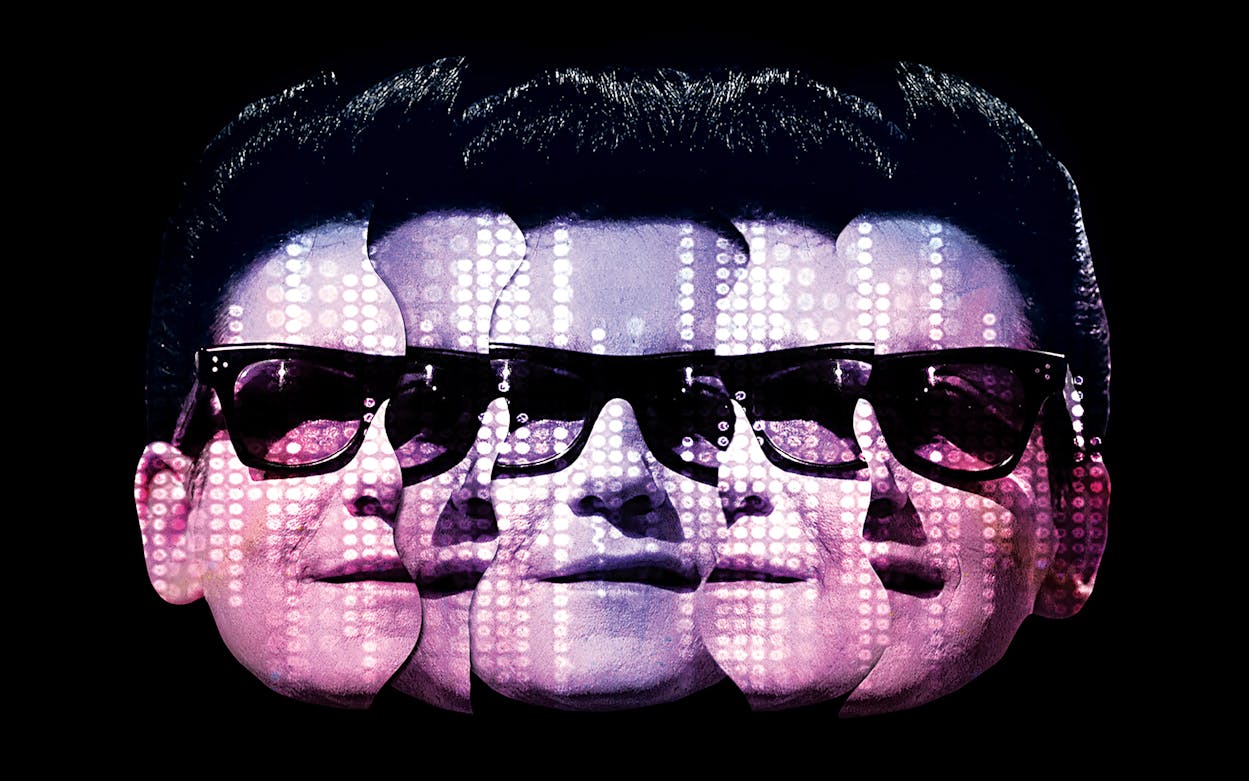

On October 1, nearly thirty years after he shuffled off this mortal coil, Roy Orbison will take the stage at the Fox Theater in Oakland, California. It’s the first of 28 dates across North America—including stops in Grand Prairie and Houston—for the deceased Vernon native, who will be joined by a full, live orchestra for In Dreams: Roy Orbison in Concert—The Hologram Tour.

The In Dreams tour kicked off this April in the UK, where Orbison enjoyed his greatest commercial success. It was an immediate hit. The laser-projected image of Orbison was beamed in front of mostly sold-out crowds during the sixteen-show run.

“The audience was dancing in the aisles. They were singing along with the songs, and most importantly, at the end of each song, they applauded,” recalls a slightly incredulous Marty Tudor, the CEO of productions for Base Hologram, which produced the show. “They were applauding a projection who can’t appreciate it. I’ve seen this hundreds of times now. I know every inch of how it’s done, and still my mind accepts it as real.” (Note that Tudor, perhaps unconsciously, referred to the projection as “who.”)

At the conclusion of the North American tour, in mid-November, Base Hologram—the company Tudor founded with Brian Becker in 2017, which has offices in Houston, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and New York—will take the operation to Branson, Missouri, the kitsch capital of the Midwest, which is home to oddball shows like a Jerry Springer–hosted live version of The Price Is Right and a Dolly Parton–themed dinner-theater horse show, for an extended run.

The tour and residency are an experiment. By the time hologram Roy leaves Branson, Becker and Tudor hope they will have gleaned sufficient information about who and where their audience is and what people like (or don’t) about hologram performances. With that market research, they hope to implement a five-year plan that includes adding at least two acts a year to their roster of spectral artists.

“I don’t want to be morbid,” Tudor says, “but we all are passing away every day.”

Base Hologram was born after Tudor saw a hologram Tupac Shakur rapping at Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in 2012, almost sixteen years after the performer’s death. Watching Tupac’s lifelike figure share the stage with real-life Snoop Dogg, Tudor—who lives in Los Angeles and has worked in talent management and production since 1980—immediately began to envision other possibilities.

He and the Houston- and L.A.-based Becker—whose company, Base Entertainment, is the second-largest promoter of live shows in Las Vegas, behind Cirque du Soleil—began researching ways to take holograms on tour. The technology had improved since its invention in the twentieth century, but Tudor says it would take two days to set up the required onstage projector and angled glass at every stop. That wouldn’t work if Base wanted to be in a different city each night. So Tudor started scoping out solutions on the internet. “The internet is an amazing thing, because everybody puts their stuff up on YouTube,” he says. “Believe it or not, that’s how I found this technology. I just started picking the phone up and dialing.” The exact technology that Base now uses is a trade secret—Tudor and Becker decline to go into details about how it works—but they can confirm that it involves an Epson laser projector. “That’s a military-grade laser in there,” Tudor says. “If you were to crank it up, you’d probably burn a hole through the wall.”

Another company, Hologram USA, originally held the rights to create an Orbison hologram. But the late singer’s estate, frustrated with the company’s slow progress, terminated the deal in 2016 and announced the switch to Base the following year. Getting the call from Roy’s Boys LLC—the company that manages Orbison’s rights, which is overseen by his sons Alex, Wesley, and Roy Jr.—gave Becker and Tudor a chance to realize their concept with a major figure in pop music.

“Roy is a real icon,” Tudor says. “He’s someone people love. His music is still relevant. There’s a huge nostalgia component there. People made out in the car for the first time to that music. We felt there was an opportunity to tap into that.”

Shortly after finalizing the deal with Roy’s Boys (and Base’s first signing, the estate of opera singer Maria Callas), they began the lengthy development process. To create the Orbison hologram, Base hired a performer to reproduce his signature stoic stage presence (George Harrison once described it as “like marble”) and recruited Eric Schaeffer, who directed the Broadway musical Million Dollar Quartet, to helm the show. They settled on a set list and answered more abstract questions—would their Roy be the 24-year-old who had his first hit with “Only the Lonely” or the 52-year-old who experienced a career resurgence with the Traveling Wilburys? Settling on the latter era, to keep eighties songs like “You Got It” and “A Love So Beautiful” in the mix, they had a show ready to hit the road a year later.

Talking to Becker and Tudor, it’s easy to get swept up in the thrill of the technology and the creative possibilities they see. They both discuss a dream show featuring all-time jazz greats jamming together onstage: John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, and a still-breathing Wynton Marsalis, in his corporeal form, playing together at the Kennedy Center (Tudor allows that they would need to make a special mash-up that featured all of the artists’ music). They can imagine reuniting the Highwaymen, giving Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson one more chance to saddle up next to Waylon Jennings and Johnny Cash, bringing new meaning to “Ghost Riders in the Sky.” And it doesn’t have to stop with the recently departed. The company is already in the process of creating a show with subjects a couple hundred million years old, teaming up with paleontologist Jack Horner (who consulted with Steven Spielberg on the Jurassic Park movies) to bring life-size dinosaurs to museums. Tudor thinks we’re about five years away from a Blade Runner future in which hologram technology will be in people’s homes, even if it’s just to make things like FaceTime more lifelike. He sees no reason the live experience should stop at concerts, either. “I’d love to do a play,” he says.

In addition to asking just how far this tech can go, there’s another question that’s hard to avoid: doesn’t it feel icky?

Tudor has heard it before, and he’s poised to flip it right back at you. “When you watch a movie starring somebody who’s dead, you’re still watching the movie,” he says. “Why isn’t that creepy? Tell me.”

Well, there’s one very good reason it isn’t creepy. Watching the late Carrie Fisher in Star Wars: The Last Jedi might be sad, but you know that she agreed to give that performance. If Paul McCartney were to approach Becker and Tudor and ask them to create a hologram of himself for fans to enjoy after his death, that viewing experience likely wouldn’t feel as unnerving as watching the unsuspecting ghost of Roy Orbison tour North America. The Orbison show feels more analogous to seeing Fisher digitally re-created for next year’s Star Wars movie.

“Which they just announced that they’re going to do,” Tudor notes. It’s actually unused 2014 footage of Fisher, but it will be used outside of its original context. So maybe that’s fair enough.

The technology to digitally re-create dead people exists. And, at least for Orbison fans in the UK, there is a demand for it. But as the technology hastens, so, too, does the urgency to discuss the ethical questions that it raises. What happens if an estate that’s facing money troubles comes calling with an opportunity that the artist might not have approved of?

“That’s where this could really go down the wrong path,” Tudor acknowledges. “They need money, so they’re going to exploit it however they’re going to exploit it. I haven’t been in a position yet where I’m torn between the commercial or the ethical, but I always lean toward the ethical. There’s always another way to make money. But if you make a mistake ethically, you could be out of the business.”

While alive, artists have the right to control the commercial use of their image, often referred to as the right of publicity. But whether this right continues into death, governed by the artist’s estate, depends on a hodgepodge of state laws. There’s no federal law dictating the postmortem right of publicity. For Texas residents, that right remains with the estate for 50 years; for New Yorkers, there’s no such protection. Robin Williams, who died in 2014, had a provision in his will restricting the use of his image for 25 years—which will be honored because he died in California, which has laws that are similar to those in Texas. For those types of restrictions to apply nationally, it’ll take new laws. “There has been considerable discussion about the need for a federal right of publicity law to create uniformity,” says Linda Wank, a New York attorney with experience in estate law as it relates to intellectual property and the right of publicity.

The Orbisons are confident that their dad, a technophile who launched his own career by partnering with a Midland-area furniture store to get himself a show on the local television station KMID at a time when only 64 percent of households in the U.S. had televisions, would have loved the idea of performing as a hologram. “He liked to stay relevant and new,” Alex says. “This was the same kind of opportunity as what he was doing in 1954.”

Other estates are less interested in, and sometimes adamantly against, the technology. Tudor says that Base was in early talks with Prince’s estate, which was uninterested. After Justin Timberlake hastily scrapped plans to perform alongside a hologram version of the pop star at the Super Bowl in February, an interview conducted two decades earlier resurfaced in which Prince, a devout Jehovah’s Witness, called such performances “demonic.”

“We’re not out to exploit people,” Tudor says. “I’m in this business because of artists like Roy.” Even though Tudor is in the illusion business, getting it right is important to him. “I’d never want to do something that’s not authentic.”

- More About:

- Music