During his early days in the majors, before Nolan Ryan was traded to the California Angels in 1971, there were seasons when he wasn’t sure he’d show up for spring training. He’d struggled mightily with control during his six years pitching for the New York Mets, posting a less-than-impressive 29–38 win-loss record. Maybe, the Refugio-born right-hander thought, it was time to give up on his dreams, move back to Texas, and train to be a veterinarian.

But his wife, Ruth, insisted he give the game one more try, so he did. And then he bonded with the Angels’ pitching coach, Tom Morgan, and everything changed. “He got me thinking about what I had to do to be consistent from pitch to pitch,” Ryan told me. “I grew up as an overthrower because that’s all I knew: throw as hard as you could for as long as you could.” Throughout the 1972 season, Morgan worked to clean up Ryan’s delivery and help him harness two of the best pitches in major league history: a blazing fastball and a knee-buckling curve. The results that first year were dramatic: a respectable 19–16 W-L record and an eye-popping 2.28 ERA. For the first time—but not the last—Ryan led the league in both walks and strikeouts. He was still struggling to consistently get the ball where he wanted, but when he did, batters had a tough time connecting.

What followed was one of the most storied careers in Major League Baseball: seven more seasons with the Angels and then the triumphant return to Texas (definitely not as a veterinarian). He spent nine years with the Houston Astros and then five more with the Texas Rangers, making him perhaps the only professional athlete who is revered in both the Houston and Dallas–Fort Worth greater metropolitan areas.

Along the way, there was a dizzying variety of records: the most strikeouts ever, the most bases on balls, the most no-hitters, and a tie for most one-

hitters. Unsurprisingly, given his penchant for walking players, he never pitched a perfect game. Very surprisingly, one of the greatest pitchers to ever take the mound never won the Cy Young Award, an injustice that ranks right up there with Steve McQueen’s Oscar-free mantelpiece.

Ryan retired in 1993, but he’s never really left the game behind. In 2000 he, his son Reid, and businessman Don Sanders founded the Round Rock Express minor league baseball team in the suburbs of Austin—yet another Texas metro area with reason to admire him, apparently. (In November their company bought an interest in another minor league team, the San Antonio Missions.)

And then, in 2008, Ryan rejoined the Rangers, this time as team president. The ball club at the time was in sorry shape, and fans were drifting away. Determined to upend the franchise’s fortunes, Ryan deployed the same sort of methodical approach that Morgan had taught him decades earlier. “That first spring, I spent a lot of time telephoning fans who’d decided not to renew their season tickets,” he said. “I think they appreciated that somebody picked up the phone and asked them about their thoughts and frustrations.”

Ryan built a front office that reflected his decency and accountability. He dotted the organization with his own hires, but even those he inherited considered him a friend as much as a boss. “I wanted everybody

to feel respected,” he said. “And they were appreciated. I hired people I felt had the same mindset as I did and wanted our fans to feel appreciated by the leaders in the organization. I wanted that to filter down through the whole organization.”

It’s impossible to single out one explanation for a losing team turning into a winning team, but suffice to say that the Ryan-led Rangers ramped up with shocking speed: a winning season in 2009 and World Series appearances in 2010 and 2011, the franchise’s first ever. They didn’t bring home the Commissioner’s Trophy either time, but it was a big shift for a team that had won only a single playoff game in its history.

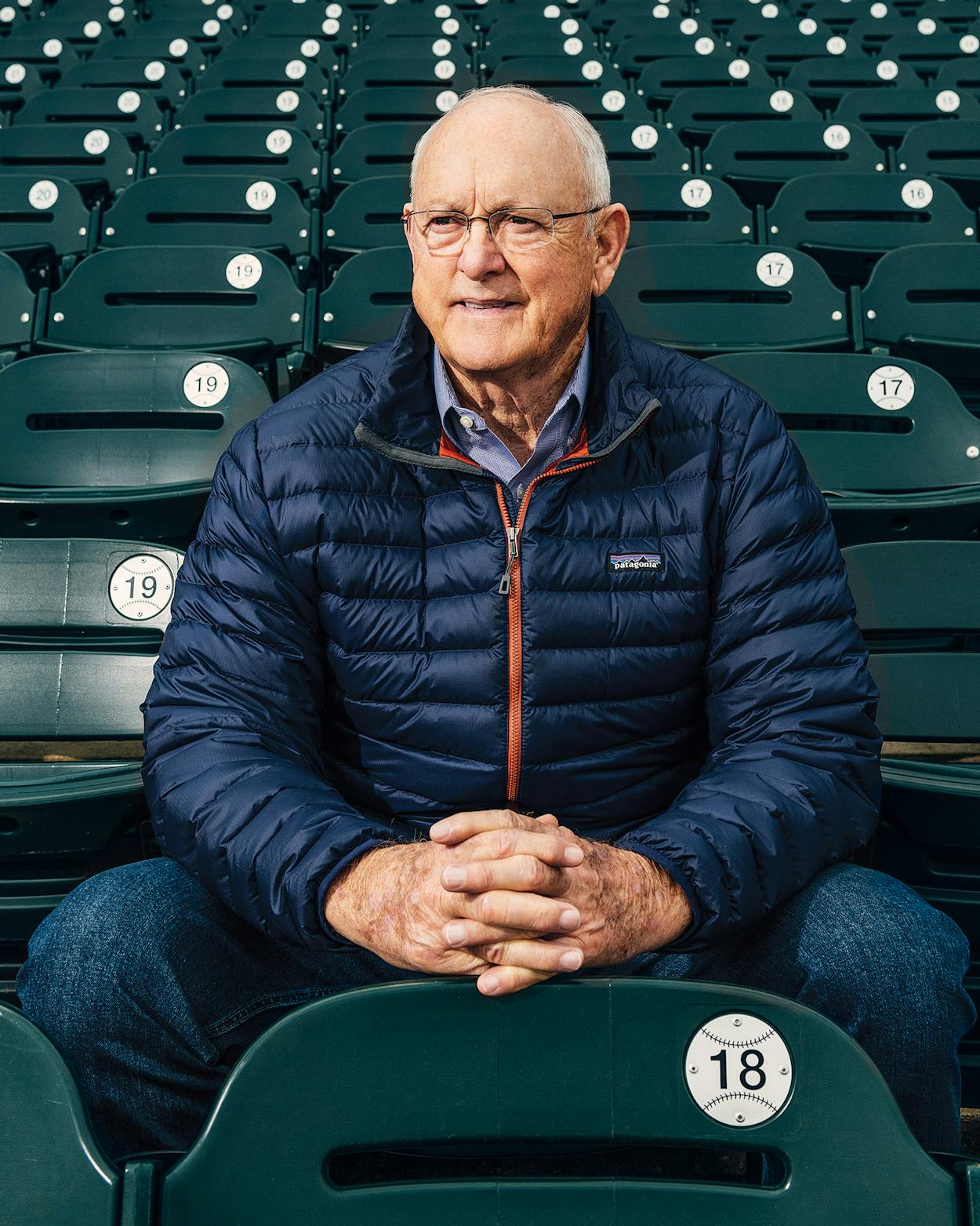

Ryan left the Rangers in 2013 and joined the Astros as an executive adviser to owner Jim Crane, helping guide the franchise’s rise to championship contention over the next six seasons. Today, he devotes his professional energy to Nolan Ryan Beef, the cattle ranching company he founded in 2000. Much of his free time is filled with school volleyball matches, football games, theater productions, and the assorted other duties of a 76-year-old grandfather. At every chance, he and Ruth make the three-hour drive from Georgetown to their second home, on a sprawling South Texas ranch. There, amid sagebrush and rolling hills, they soak in the solitude and breathtaking views.

Sometimes Ryan gives back to the state that has shown him so much love. Several years ago, when floods devastated the Fort Worth suburb of Mansfield, he turned up with an H-E-B truck and cooked steaks for those affected. “I think when you’re in a position to help people, you want to do it,” he said. “I take pride in the fact that my children feel the same way.”

He still pays attention to the game that made all of it possible and has no shortage of opinions about how baseball is played today. Ryan earned one of his more notable stats during his second season with the Angels, when he threw seven consecutive complete games. To put that number in a contemporary context, that’s one more complete game than any major league team’s entire pitching staff had during the 2022 season.

“That’s what you were expected to do in those days,” Ryan said. “When you started a game, your intent was to finish it. On that Angels staff, we only carried nine pitchers; now every team carries thirteen or fourteen pitchers, and they use them differently. A lot of teams didn’t even have closers back then.

“It’s changed because of the people running the game,” he continued. “I think a lot of pitchers are underutilized—they could pitch later into the game. Teams just aren’t taking advantage of the talent they have on their staff.” Ryan thinks in particular of the pitcher who might be his modern-

day heir, Dallas native Clayton Kershaw, a devastating fastballer who plays for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Last April, Kershaw was pulled from a perfect game after seven innings. That sort of thing doesn’t sit right with Ryan, who probably would give an eyetooth to have pitched a perfect game. “I understand the precautions they’re taking,” he said, and you could almost hear him shaking his head in frustration over the phone line. “But I don’t think it’s necessary.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Nolan Ryan’s Extra Innings.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Sports

- Nolan Ryan

- Arlington