This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

A full moon sat in the cloudless sky over the Opryland U.S.A. complex outside of Nashville on the October night of the 1981 Country Music Association awards ceremony. Sleek limousines swooped in and out at the front entrance of the Opryland Hotel, whisking ladies in sequined outfits and men in tuxedos to the Opry House. Meanwhile, in one of the rooms of the hotel, a drunk George Jones was getting dressed to go to the ceremony. He refused to wear a tux; instead he donned an open-collared frilled shirt and a brown Western suit. He had spent the whole afternoon—after having his hair done—hiding out in the hotel, drinking, in the charge of a man whose job it was to see that the elusive star didn’t escape, as he was wont to do. George didn’t really care about the highfalutin awards show, even if he had gotten the male vocalist and single of the year awards the year before. He figured that after thirty years it was about time.

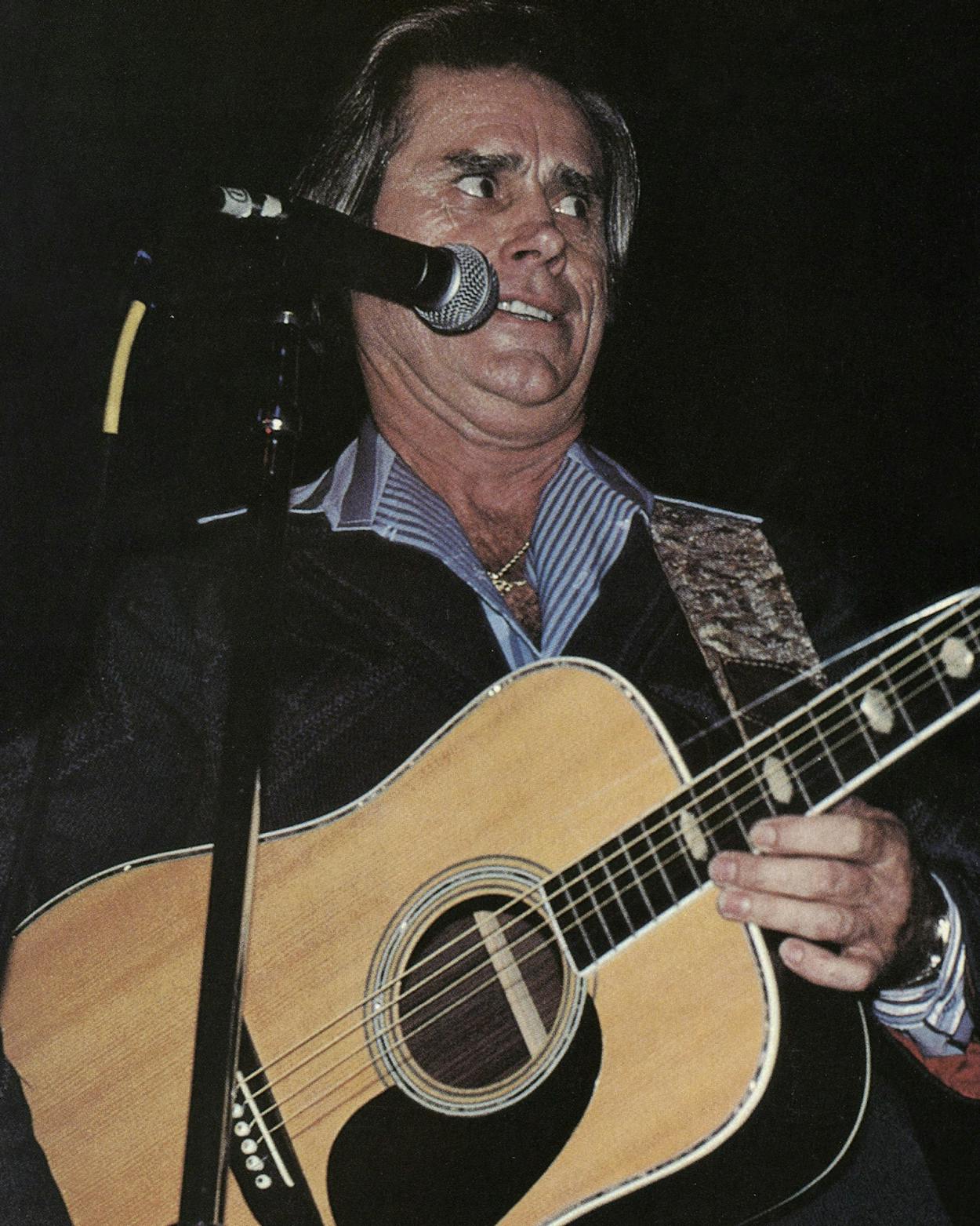

But the executives from CBS, which now owns Jones’s contract, weren’t going to let him get away this time. Looking like a herded animal—67 whipcord inches of blood and guts with a face as rivuleted as the base of a volcano, out-of-focus eyes that verged so close together as to almost collide in the middle of his face, and graying muttonchops—George was surrounded by a phalanx of people when he finally walked slowly down the hotel hallway to the door.

A limousine had been sent to the side entrance to pick him up—none of his companions wanted his picture taken in his drunken state. A woman in a fur-trimmed white gown had George by the arm. She looked as though she thought he was about to crumple into a heap at her side. Bent-shouldered, George shuffled down the steps, his female friend never letting go of his arm.

I Am What I Am

George Jones’s songs about drinking and lost, illicit, or unrequited love have long sustained hardworking and hard-loving people through their arduous lives. Whether they drove a truck, worked as roughnecks, farmed, or cut hair for a living, they listened to the music of George Jones on their radios and record players. They looked up to him as someone who could, if he wanted to, make it, regardless of his inadequacies or the circumstances of his birth. George’s maverick lifestyle—a testimony to the unbridled emotion found in honky-tonk music—makes his expression of that music much more believable.

Infinitely fallible, George Jones has a violent temper. He has bruised more than one woman’s face; he carries a gun and has occasionally used it to threaten or frighten people; he lies blatantly or runs away to avoid confronting difficult situations; he is indifferent to the value of money and thoughtlessly borrows and squanders it. But these aberrations of character are at least tempered, if not balanced, by an extreme generosity, a homegrown honesty, an inherent humility, and a tender heart—that is, when he’s sober. He detests people who put on airs, although he himself has grown to expect a certain amount of deference from the go-fers and hangers-on who surround him. And invariably, regardless of how alienating George is, people—from his producer and manager to his fans and family—forgive him.

In general, country music has the most loyal of fans. George, of all the country stars, has given his fans plenty of reason to abandon him, yet they will come a thousand miles to see him, again and again, knowing full well that he might not show up. There is no country artist more beloved by his fans, no one whose interpretations are so awe-inspiring to other musicians, from Waylon Jennings to Ray Charles. Often compared to Hank Williams, George is too modest to claim to stand alongside the Shakespeare of country music. Whereas Williams’s early death made him into a tragic icon in country music, George’s rattlesnake constitution and refusal to succumb to adversity make him seem more pathetic than tragic. And though Hank and George are equally charismatic, George is the better singer. He ranks alongside Frank Sinatra and Billie Holiday as a master vocal stylist; his ability to wrap his voice around a lyric, sliding it up and down with remarkable ease, or to emote through clenched teeth is a constant source of wonder to his fellow musicians. Unlike Sinatra, though, George has never been one to manipulate the media. Of the two, he stands closer to Billie Holiday as someone who seemingly has no control over his life or his prodigious excesses. He doesn’t pretend to understand his own power; he is in fact intimidated by it, preferring to run away rather than to face it.

Despite his loyal following and his prolific output of more than a hundred albums, George was largely ignored by the intelligentsia of country music until 1980, when he garnered Country Music Association awards for male vocalist of the year and single of the year (“He Stopped Loving Her Today,” a gloomy tale of a man who ceased to love a woman only after he died and was carried away, taking his love for her with him). The laurels for this song carried over into 1981, when he won the coveted Grammy from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences for best male country vocal performance of 1980, the Academy of Country Music 1980 awards for male vocalist of the year, song of the year, and single of the year, and the Country Music Association’s 1981 award for male vocalist. After the album I Am What I Am (which included “He Stopped Loving Her Today”) went gold—selling 500,000 copies—CBS Records executives realized that there was more money to be made off George than they had thought possible, and in December 1981 they offered him a new contract—one of the best for a recording star in country music history.

Since George came from humble origins, the trappings of success were at once a temptation and a travesty for him—a temptation because those trappings could easily become the end rather than the means, and a travesty because they removed him from his roots and deprived him of the very feelings that inspired him to begin with. He has always refused to cater to the slick pop-country sound that came into existence in the sixties in Nashville. In this respect, George is a purist, for though he may have left the country, no one has ever successfully taken the country out of him.

Poor Man’s Riches

On September 12, 1931, in Saratoga, deep in the Big Thicket, George Glenn Jones came into the world as a breech baby with a broken arm. Early that morning his father, George Washington Jones, took all the kids over to a cousin’s house six blocks from his half wood-frame, half log house, while his wife, Clara, waited for the child to be born. It was the same house in which she had given birth to her seven other children and in which they spent most of their formative years, all of them sleeping in one big room. In the late afternoon, George Washington went to get the kids and told them, “You’ve got a twelve-pound baby brother.”

George Jones grew up in a rural part of East Texas. His father worked as a truck driver in Kountz and later, when they moved to Beaumont, as a pipe fitter in a local shipyard. His wife was of Irish descent, and he was part American Indian. A strict man with a drinking problem, he must have seemed unapproachable to the kids. George tells tales of his father’s coming home from a bender and chasing him with stove wood or being in such a state that his entire family would have to flee to someone else’s house to avoid him. According to W. T. Scroggins, who is married to George’s oldest sister, Helen, “George’s daddy did like most men used to do then—they’d git their payday and they’d git their groceries an’ ever’thing and then a lot of ’em’d git drunk.” Irrational rages characterized his mood when he was drunk, a trait that he passed on to his son.

Both of George’s parents loved music, and it was as much a part of George’s growing up as was chopping wood to fill the stove. They got their first radio in 1938, and on Saturday nights they would listen to WSM’s Grand Ole Opry out of Nashville. George always instructed his daddy to be sure and wake him up if he was asleep when Roy Acuff or Bill Monroe came on. Family members recall him as a four-year-old walking barefoot down a dusty road, banging on a pot and singing as loudly as he could. At age five George would sit on his cousins’ front porch and play with the guitar. “He’d lay it down ’cross his lap,” says W.T., “ ’cause he couldn’t even hold a guitar. He never cared about nothin’ but country music.” He was all ears, pug nose, and cowlick, with close-set, slanted hazel eyes and a square jaw. He was a serious-looking child —until he smiled his wide moon smile.

Except for a boy named Ishmael Spell, who was the same age but stood a whole head taller than he did, George didn’t have many friends as a child. “It seems like he was in a dream world,” says Helen Scroggins. “He’d sit for hours, just by himself, drawin’ in the sand with a stick or leanin’ up against a tree. He didn’t have much to do with nobody. He was just a loner.” But his family made up for his lack of friends. “We spoilt him.” says Helen of his mother and brother and sisters. “We was pretty proud of him.”

George’s dad bought him a cheap Gene Autry guitar when he was eleven, and George thought it was the best in the world. He would stand in front of the local cafe and strum and sing for anybody who would listen. He played a lot in the Baptist church his family attended, until later when he couldn’t reconcile playing in honky-tonks with playing in churches.

George couldn’t see any use in school and was continually truant, especially after the family moved to Beaumont. His favorite hangouts when he skipped school were the radio stations in Beaumont—KRIC and later KTRM. He and a sidekick would appear every noon to hear Richard Prine (“King of the Hillbilly Drummers”) and his band aired live on the 12:05 show. The boys would stand with their noses pressed against the glass door of the studio, avidly listening and watching. By the time he had gone through the seventh grade twice, he convinced his family he should quit school.

At seventeen, he got his first job as a deejay—which lasted only a few months—on Jasper’s KTXJ, where he had a half-hour afternoon show. Shortly thereafter he started playing lead guitar with Eddie and Pearl, a husband-and-wife team who were the first hillbilly musicians in the area. She played bull fiddle (stand-up bass), and he played guitar and sang. They were devoted to each other, but they made an odd couple—Eddie was handsome and dapper, but Pearl looked much older. George shared their trailer with them and got room and board plus $17.50 a week, traveling with them to gigs around Beaumont and in Louisiana. Eddie and Pearl were the first of George’s many surrogate parents. At that time, he didn’t really have a place to call home. His father was a town drunk, and his mother moved about from one of her children’s homes to another.

By the time George was in his late teens, he had played in every beer joint around, sitting in with any band that would let him when he wasn’t playing with Eddie and Pearl. He was lucky if he got $10 a night. It was during those forays into dingy taverns that George first started drinking.

Eddie and Pearl had a six-thirty morning show, first on KRIC and then on KTRM. One day Hank Williams came by the station to sing. George backed him up with electric guitar but could hardly hit a lick because he was so awestruck. At the time, George was known more for his imitations of his idols, Roy Acuff and Hank Williams, than for his own interpretations. After the show, Williams gave George some good advice: he told him not to try to imitate anyone but to develop his own style. George went to see Hank’s show that night in Beaumont and was thrilled when Williams remembered his name and announced to the audience that he was going to sing “I Just Can’t Get You Off of My Mind,” which a young man by the name of George Jones wanted to hear.

Tender Years

In 1950 the nineteen-year-old George was working as a house painter for a Beaumont contractor and playing music at night. The contractor had a daughter named Dorothy, and she and George soon found themselves walking down the aisle. Dorothy’s parents gave George a fancy guitar for a wedding present.

The young couple lived in her parents’ house, and the strains that commonly arise in such a living arrangement soon appeared. One evening George asked Dorothy to feed his rabbits in the back yard, because he was running late for a gig. He later told Helen, “They acted like I’d insulted her. They said, ‘Don’t you ask my daughter to go feed no rabbits!’ ” He decided they had to move, and he took Dorothy to look at an apartment he had picked out. But she was reluctant to start homemaking on her own, and one day at Helen’s she told George, “I didn’t wash no dishes or cook before I married you, and I don’t intend to now.” They separated before their daughter, Susan, was born. Shortly afterward, they were divorced.

The judge decreed that George should pay $30 a week child support. “Back in them days thirty dollars was hard for a man to make, let alone pay a woman,” says W.T. “Ever’ time he got a week behind with the child support the judge would throw him in jail. We’d have to pay the child support and git him out. He’d always call us. So finally the judge recommended he go in the Marines.” For the next two years, from November 1951 to November 1953, George did his stint, stationed at Camp Pendleton, California. The child support payments went directly to Dorothy.

In 1952, while George was back in Beaumont on leave, he caught a Lefty Frizzell show at Yvonne’s, the Gilley’s of the time. Frizzell was one of the biggest country music stars, and George followed his music closely. Lefty sang only a couple of songs that night because he’d been injured in a car accident the night before. His managers, Jack and Neva Starnes (who owned a nearby club bearing her name), approached the perky, crew-cut George and asked him to take Frizzell’s place. Sparkling clean in a starched white cowboy shirt and shiny black boots—all five feet seven inches of him—Jones was ready and willing to sit in for Frizzell for the rest of the night.

While he was stationed in California, George once went AWOL to Bakersfield to play on KUZZ’s Cliffie Stone’s Hometown Jamboree along with Buck Owens, another struggling country artist. As soon as George got out of the service, the Starneses began booking him all around Texas and Louisiana, including Shreveport’s Louisiana Hayride, where he first saw Elvis Presley.

Jack Starnes, along with H. W. “Pappy” Daily of Houston, had formed Starday Records the year before. George was one of the first artists they signed, and his first single, “There Ain’t No Money in This Deal,” was cut in the Starneses’ living room in Beaumont, with egg cartons tacked on the wall to dampen the sound. Their fourteen-year-old son, Bill—who later would be involved in other ventures with George—was in the next room running the tape recorder. The record wasn’t any great success, but George was delighted nevertheless. His first album, George Jones Sings, was released soon after.

Pappy Daily, Starday’s producer, hit it off with George from the start. He recorded George for the next twenty years, and George found support in him that he would never again find in any individual in the music business. Pappy was never officially George’s manager—their handshake was enough—and he advised him not to sign a personal management contract with anyone. George has since signed many contracts and regretted every one.

Now a white-haired octogenarian who still works three days a week at Glad Music Company in Houston, Pappy admits that he indulged George more than he did his own children. “George Jones is the best kid I ever knew,” he says. Whenever George needed money, he’d call Pappy, who would give him an advance from his royalties—as much as $20,000—for anything from a swimming pool to a bus payment.

Although George’s career picked up considerably after he signed with Starday, he was still playing any job he could get. “If he got thirty-five dollars a night he thought he was in high cotton,” says Pappy. George had just cut his first single with Pappy, “Let Him Know,” when he met Shirley Corley, a carhop at a Prince’s Drive-in in Houston. Flirting with her, he flashed his new record. Shirley was an attractive, petite East Texas eighteen-year-old, as country as they come. She was more taken with George’s cute country-boy personality than with his would-be star status, and she married him two weeks later. “I was crazy about him,” says Shirley. “You know how you get a crush on somebody when you’re young—I was smart enough to know really that I shouldn’t have married him, but I did.” He told her he’d never really had a home or anybody to love him and take care of him, and Shirley was more than willing to give it a try. The union lasted fourteen years, and they had two children, Jeffery and Bryan.

In 1955—the same year his first son was born—George was hired on as a deejay at KTRM in Beaumont. During that same period, J. P. Richardson, whom everyone knew as the Big Bopper, had an ethnic program on which he played what they called Harlem music. The blacks in the area were certain that the Big Bopper was also black, so convincing was his accent. Slim Watts, another deejay with KTRM, had a band named the Hillbilly Allstars. Slim was the one who gave George the nickname Pee Willicker Pickle Puss Possum Jones. Eventually the name was shortened to Possum, and George still occasionally refers to himself as Old Possum.

In 1956 George had his first hit record, “Why Baby Why,” written by a Beaumont songwriter named Darrell Edwards. It went to number four on the top ten country singles chart and stayed in that position for fourteen weeks. With the success of that one record, George decided to head for Nashville in August of the same year. He stopped by W.T. and Helen’s on his way to show them the diamond ring for which he’d gone in debt. He’d bought a secondhand car, too, and he told W.T., “I don’t know whether I’ll ever make it or not, but I’m goin’!”

The Race Is On

Nashville, even today, seems more like a town than a city, with its frame houses, old stores with dilapidated neon signs on the fronts, and brick buildings along the hilly, tree-lined streets. In the area around Ryman Auditorium—former home of the Grand Ole Opry—are blocks of small honky-tonks with their usual contingents of winos and street people. When George arrived in Nashville, the music industry hadn’t yet evolved into the city’s major preoccupation. Nashville was still a down-home place, even though many longtime residents considered the influx of “hillbillies” to be downgrading to the area. As the years went by and people in the music industry realized the considerable potential for moneymaking afforded by country music, more and more record companies came to set up shop there.

George was a rube in Music City if ever there was one, and without Pappy he might never have reached the stage of the Grand Ole Opry, which was the goal of every country musician. After several unsuccessful attempts, Pappy got him a guest spot on the Opry, and from then on George recorded in Nashville.

After “Why Baby Why” George didn’t have another hit until 1958, when he recorded “Treasure of Love.” In 1959 he recorded “White Lightning,” written by the Big Bopper, with an electric rockabilly sound. Practically every year since then, George has had one or more songs in the top ten country hits. With Pappy as his producer, he recorded—to name but a handful—“The Window Up Above” (one of the few songs he wrote by himself), “Tender Years,” “She Thinks I Still Care,” “A Girl I Used to Know,” “You Comb Her Hair,” “The Race Is On,” and “Take Me.”

George’s career peaked again when the music trade magazines—Cash Box, Billboard, and Music Reporter—named him country male vocalist of the year in both 1962 and 1963 for “She Thinks I Still Care.” That song crossed right over to become number three on Houston’s pop charts, an unprecedented event—in George’s history, at least. He was so suspicious of music other than country that he failed to show up for Larry Kane’s American Bandstand–type television show in Houston when he was scheduled to appear.

George always was—and still is—a failure at keeping promises, especially in relation to his constantly changing managers, and this tendency spilled over into his family life. Shirley became inured to driving to the airport to pick him up only to have him not be there. From the beginning of their marriage she would call W.T. to go find George when it was time for him to go on the road. W.T. was the only one in George’s family whom he looked up to—W.T. didn’t drink—and George regarded him as a kind of older brother.

Once W.T. went looking for him at a Holiday Inn in Beaumont when George was supposed to make a flight to Nashville. The people at the front desk finally gave him George’s room number after W.T. threatened to knock on every door in the motel. When W.T. knocked at the door, George yelled, “Who’s there?” and his brother-inlaw said, “It’s me—W.T. You’d better open up unless you want this door kicked off’n its hinges.” George opened the door wearing nothing but his undershorts and cowboy boots. He’d been watching television with a bucket of beer for company. He said, “I guess I’d better go, then.” He got dressed and followed W.T. out like a lamb.

In 1960 George and Shirley had moved to the Beaumont suburb of Vidor—a haven for the Ku Klux Klan—where it was cheaper to purchase a house. In 1961 they bought a bigger house and another one nearby for George’s parents. George was making up to $750 a performance—big money for those days—and enthusiastic plans for the future accompanied his increased income. He had always dreamed of owning a spread and raising horses and cattle, so in 1965 he bought sixty acres on Lakeview Road in Vidor and built a two-story mansion, a horse show stadium, and a barn. He called it the George Jones Rhythm Ranch and had plans for horse shows and country music shows. George was full of ideas, but he was never a good businessman. He loved to wheel and deal, but none of his projects sustained his interest for long. The ranch project and then his marriage to Shirley folded.

Shirley now lives with her current husband, John Clifton “J.C.” Arnold, in the low-slung ranch-style house that she and George bought. The house is plushly decorated, with butterfly motifs in every possible place, from the wallpaper in the bedroom to the lampshades in the living room. Today Shirley is as vital and beautiful as any 45-year-old woman could hope to be. J.C.—235 pounds of good ol’ boy bulk—has been a good husband to her and a fine father to George’s kids.

Shirley blames the demise of her marriage to George on his drinking and being on the road. Never too impressed with him as an entertainer, Shirley stopped accompanying him to shows early in their marriage, because she never knew when he was going to leave her stranded somewhere. Even when he was home, he seemed to prefer spending most of his time out with his drinking buddies, and Shirley didn’t think he treated the children right. “That’s the only thing that bothers me,” she says. “Not that he was mean to ’em, just that he didn’t ever have any time or any love for ’em.”

George left Texas after he and Shirley split up. Always one to play upon people’s pity, he called W.T. on his way out of town, saying he’d given his last penny to Shirley and needed to get back to Nashville. W.T. borrowed $1000 for him. About two weeks later, George telephoned Bill Starnes, Jack and Neva’s son, from Oklahoma City and asked him to become his manager. Bill agreed, and they moved to Nashville and rented a house together. George returned only to visit his sons and family or to play a show. He took his and Shirley’s house in Lakeland, Florida, as his share in the divorce settlement, leaving Shirley with three mortgaged houses in Vidor and half of the writer’s royalties on his songs.

In 1968, George—then 37 years old —was on top of the country heap. As Mr. Country and Western, his popularity would only increase over the next ten years, especially after he married Tammy Wynette.

Take Me

George Jones and Tammy Wynette became country music’s most celebrated couple, and their relationship provided a steady stream of gossip for their fans. Tammy first met him in 1966 when she and songwriter Don Chapel, who later became her husband, tried to pitch him a song. They found him in a motel room, wearing silk pajamas and watching television with a lady friend. Tammy left that day heavyhearted because he had seemed oblivious to her. Tammy was attractive, but it was her voice that George noticed first. Later that same year he heard “Apartment #9,” her first hit single, on the car radio and commented on what a good singer she was and predicted that she would make it to the top. Soon they were being booked on the same shows by concert promoters, and they developed a nodding acquaintance.

It was a surprise to her when, in 1968, George showed up at a benefit in Red Bay, Alabama, where she had grown up. She had mentioned the concert to Bill Starnes a week earlier and asked that George come. Bill told George about it but never expected that he would agree. The day of the concert, on impulse, George decided to go, so they jumped in his new Eldorado and drove down to Red Bay. Tammy visited with George in her bus for a few minutes while the band played the opening numbers. As she left to go onstage, she gave George a peck on the cheek and said, “I love ya, George.” George responded, much more seriously, “I love you, too, Tammy.” After the performance, he and Tammy met briefly and embraced with considerably more gusto.

The next day, Tammy called George and they talked at length. When they got off the phone George told Bill to pick Tammy up and bring her over to his house—she was at a shopping center in Madison, Tennessee, a Nashville suburb. Tammy stayed at George’s for a few hours, and when Bill came back to get her, George was irretrievably in love.

Three days later George and Bill were invited to the Chapel house for dinner. Tammy had been playing George’s new record, “I’ll Be Over You When the Grass Grows Over Me,” which, ironically enough, had been written by her husband. Don and Tammy had been arguing all day over George. When the guests walked in, everyone was tense. They ate a good dinner—Tammy is a great cook—and then moved from the dining room into the kitchen and sat at the table. Out of the blue, Don said, “Tammy needs to be with you, George. She loves you and she needs to be with a big star like you instead of a nobody like me.” Tammy pshawed the idea and told him not to talk that way. Finally, after Don had said the same thing several more times, George got up and knocked over the kitchen table, saying, “You’re goddam right she loves me, and I love her, too!” And with that, Bill had two little girls and two suitcases in his hands, Tammy had a baby in hers, and they were all out the door.

Tammy and George could hardly stay apart—the first year they spent $300,000 on jet charters alone to squeeze their reunions into their separate schedules. Within a month, thanks to Bill Starnes, Tammy’s marriage to Don Chapel had been annulled.

At a show in Dallas George insisted that Bill introduce Tammy to the audience as Mrs. George Jones. As Bill recounts it, “I went in this building with nine thousand people in it and all these other country stars and announced that George was on the bus and he’d be out in just a few minutes, but that he wanted me to introduce his new wife, Mrs. George Jones. And I could see the people lookin’ at one another. And I said, ‘You probably know her as Tammy Wynette,’ and they just went ape. It was somethin’ to behold.” Tammy and George didn’t actually get married until February 1969, nearly five months later.

George wanted to see Tammy become a star—and she was certainly impatient to make it—but at the same time he was bored and jaded by stardom. As W.T. puts it, “When Tammy and George were married, he’d done made it. And he loved to come home and stay two or three months. ’Course, Tammy was a lot younger’n George, and she wanted to keep making shows, see. I think she was wantin’ to go bigger—she wanted to git big as George.”

The love that bound George and Tammy was of the soulful, charismatic sort. On the strength of that affection, Tammy hoped to bring an end to the self-destructive patterns that had held sway in George’s life for so long. Even before they were married, Tammy witnessed George’s drunk and violent side, but she made the mistake of thinking that he would change once he settled into married life. After it became clear how serious his drinking problem was, she began nagging him about it. But Tammy handled George, even when he was drunk, with more patience than he deserved. On one occasion when he came in drunk and passed out, she was determined that there was no way he was going to go out and drink some more when he woke up, so she took all the car keys—including the golf cart keys—and hid them under her mother’s bed. When she checked later and found him gone, she was astonished to discover that he’d escaped on a lawn mower.

Their only method, however stopgap, for alleviating problems in their marriage was to move. They moved to Nashville in 1972 and changed residences a number of times. George loved to decorate houses; his favorite style was Spanish colonial. His bedroom was done in red, black, and white and had a huge four-poster bed and carved mahogany furniture. Tammy’s taste ran to pink rather than red. In their antebellum mansion south of Nashville, she decorated her bedroom entirely in pink: shag rug, circular bed, stuffed animals. The chandelier even had pink bulbs in it.

One of Tammy and George’s main difficulties was that they were with each other so much of the time. They started doing shows together shortly after they were married, but George was his usual undependable self, often perpetrating one of his famous disappearing acts whenever he wasn’t sure of his reception. Tammy carried the show for him on those occasions, but it made her angry, especially when the querulous fans would demand, “Where’s George?” and she would have to tell them he wasn’t going to appear.

Though George has been known to say repeatedly that all he wants out of life is peace of mind, it eluded him in his marriage to Tammy. Toward the end of the six years they were together, after their daughter, Tamala Georgette, was born, Tammy bluffed him into giving up drinking by demanding that he choose between her and alcohol. It worked for a year, and George was a model, sober husband. But Tammy hadn’t had any hit records recently, and she would often cry herself to sleep at night. George tried to comfort her, but eventually he took to drinking again in defense against her depression. It was the last straw for Tammy when, right before a projected Christmas vacation to Acapulco, he took off with a couple of drinking buddies. When she asked for a divorce this time, she got it.

According to Helen, George and Tammy still have a deep affection for each other. “I think George is over Tammy now,” she says, “but there’ll always be somethin’ special between ’em. But she wanted her way and he wanted his way. They was too much alike.”

Things Have Gone to Pieces

It was the end of Mr. and Mrs. Country Music, but their fans never could accept the separation and are still waiting for them to reunite. To this day, George will quip about himself and Tammy and intersperse her name in his songs, and Tammy still has to endure the irrelevant queries of “Where’s George?” from her audiences.

George had a mountain of problems before he met Tammy, but their breakup only made them worse. It became obvious to Tammy that she couldn’t break his cycles of erratic behavior; he was still an out-of-control drunk. In his songs about the degenerative effects of whiskey, his own life and the misery he sang about became one—in effect, he excused his own acts on the basis of living his art.

One of the major consequences of George’s marriage to Tammy was his break—at her insistence—with his producer of twenty years, Pappy Daily. George signed on with Tammy’s producer, Epic Records’ Billy Sherrill, two years after they were married. The two men’s styles were very different. Pappy may not have been as technically proficient as Sherrill, but he staunchly refused to cater to the pop sound that took over Nashville in the late sixties. Sherrill, on the other hand, preferred complicated arrangements with symphonic string backgrounds, even though they were poorly suited to George’s grass-roots sound. And whereas the benevolent Pappy was genuinely fond of George, Billy Sherrill saw him as merely an appendage to Tammy. In the end, not only did George lose Tammy but through her he lost Pappy Daily, his main link to his roots.

Nonetheless, in the ten years that George and Billy Sherrill have worked together, Sherrill has garnered him 22 top ten hits. George and Tammy continued to record together for a while after their divorce, and the hits kept coming. They recorded “Golden Ring” and “Near You,” both of which went number one. In 1977 they did “Southern California,” but that was their last collaboration until 1980, when they did “Two Story House.”

Adrift without Tammy and wanting to get back a sense of where he belonged, George left Nashville and turned to an old songwriting pal, Earl “Peanut” Montgomery, and his wife, Charlene, in Alabama. The Montgomerys, being plain country people themselves, provided George with the ideal surrogate family. Charlene took charge of George’s house; Peanut took over his cars as he got tired of them; and Charlene’s sister, Linda Welborn, kept him company, since he was petrified of sleeping alone in a house at night. Linda and George lived together for four years.

But even old friends have occasional disagreements. A schism developed between George and the Montgomerys when Peanut got religion and quit drinking—and tried to persuade George to do the same. Peanut even bought a church and started preaching. In an argument ostensibly over money (but more likely over the fact that Peanut wouldn’t drink with George), George shot point-blank at Peanut, from one car to another. Luckily Peanut’s car door stopped the bullet. Out the same night on $2500 bond, George claimed that the press exaggerated the incident and that he and Peanut were still on good terms.

George’s relationships with his series of managers—some of whom had only their status as good ol’ boys to qualify them—weren’t improving either. One problem with having a manager is that even though the star is the one who brings in the money, he works for and gets paid by the manager. George’s built-in hatred of authority made it hard for him to accept that arrangement. He continually embarrassed his booking agents by not making his shows. George’s resentment at being hounded and caged with a baby-sitter overrode his sense of obligation to his fans and made him more uncooperative than ever.

In January 1979, on one of his visits to Nashville, George met a cupid-faced, intelligent young woman named Linda Craig, who tended bar at the Sound Track in the Best Western Hall of Fame Inn. The Sound Track is a low-ceilinged hangout for record industry executives and musicians, as well as tourists who make the Country Music Hall of Fame their base while taking in Music City’s sights. George spent a lot of time there, and Linda sent him a drink on the house whenever he came in. One night he came in by himself and sat down at the bar and talked with her. “I felt really close to him right away. At first we were just friends, but it gradually got into a romantic relationship.”

George was a model companion for about the first three months, but eventually he became difficult to deal with. He was using lots of cocaine, missing concerts (at least fifty dates in 1977 and 1978), and being sued by a number of promoters. He owed CBS Records $400,000, and in October 1978 Tammy sued him for $36,000 he owed in child support. He filed for bankruptcy in December 1978, with more than $1.5 million in debts. His use of cocaine had hurt his voice, and for the next year, during the time he was with Linda Craig, George grew increasingly paranoid about both Shug Baggott, his manager at the time, and Linda.

Linda had refused to accept presents from George, not wanting to be accused later of using him. But her loyalty was lost on him; cocaine paranoia took over, and he accused her of being in league with Baggott against him. Linda described late 1979 as particularly difficult for her and George. “It was like George had all this frustration and anxiety,” she said, “and he’d accuse people of things they hadn’t done—even real close friends of his—and they just didn’t want to deal with him. I was in love, and I wasn’t going to turn on him, no matter what.”

Finally, in December 1979, the suicidal George checked into a Birmingham hospital. He was down to 96 pounds and suffering from alcoholism, drug abuse, and malnutrition. But as predictably as George Jones falls, his friends and admirers always pick him up again. When George left the hospital after a month, he was surprised and gratified by the support shown by fellow musicians, especially Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings, who paid off his hospital bill and got a bus and band together for him. Tammy’s career wasn’t doing too well at the time either, so they agreed to appear together again, and her brother-in-law Paul Richey took over as George’s manager. It didn’t last long, though. Eighteen months later, George was still in debt, even though he was working more and more.

After a performance at Billy Bob’s Texas in Fort Worth in June 1981, George complained to Billy Bob Barnett about his management and said he was broke, with less than $300 in his bank account after working for more than a year and making at least $15,000 a performance. Billy Bob was sympathetic and suggested that he take over as manager. Although the affable ex-football player had made himself a millionaire several times over, he’d had no experience in managing country music stars the likes of George Jones. But he was a genuine fan of George’s, and as a businessman he was intensely interested in the money George would generate. Billy Bob was prepared to sign a contract that would make him legally responsible for George’s unbelievable pile of debts; he would also take over those suits that were still pending against Jones from the concert dates he had missed. It seemed that George had finally found a manager who was really on his side.

One month later, Pee Wee Johnson, a Nashville club and restaurant owner who was a good friend of George’s, gave a mammoth going-away party for him. Billy Sherrill, George’s producer, presented him with a plaque with a gold record on it for the album I Am What I Am. Fourteen hundred people showed up for the party—they were all but hanging from the ceiling—and George was ecstatic, playing a ninety-minute set.

But true to form, George got cold feet. He disappeared and then called from Alabama the day after the contract signing was to have taken place to tell Billy Bob that he had decided to manage his own affairs. He agreed to make up part of the money Billy Bob had spent by playing some shows at Billy Bob’s Texas in Fort Worth, but he has yet to make any of them. George’s silver Mercedes, which Billy Bob paid off the note on and drove from Nashville to Fort Worth, is still sitting in the garage of the house Billy Bob bought for George.

These Days I Barely Get By

George Jones may never actually put a gun to his head, but he nonetheless seems bent on destroying himself in his nonchalant fashion. In late March of this year, George and his current girlfriend, Nancy Sepulvada, were driving from Muscle Shoals, Alabama, to Texas. They were stopped outside of Jackson, Mississippi—she had been driving 91 miles an hour on the freeway and he was charged with possession of cocaine and public drunkenness. On the way back to Muscle Shoals alone the next day (after arguing with Nancy and her daughter), George totaled his Lincoln Continental, flipping it seven times, but he emerged unscathed except for a few scratches on his forehead. The police found an empty vodka bottle in the wrecked car. Shortly afterward, he entered the same Birmingham hospital he had been in three years earlier.

But barring a major metamorphosis, all the hospital stays in the world will never unravel the mystery that is George Jones. His conflicts are multiple and irreconcilable. Some are traceable to his upbringing, others to his success. In the fundamentalist Christian faith of his parents, drinking, dancing, and philandering were all taboo—yet he witnessed his father breaking the first two of those taboos and certainly must have seen many other people merely nodding to convention while they did exactly as they pleased. Success has driven a wedge between him and his family, and although he is extremely generous to them, they nevertheless continue to plague him in his personal life.

Other inconsistencies can be traced only to the workings of an unfathomably complex mind. Although he has always craved a solid family life, he has destroyed any potential for it in each of his marriages. And even though he’s been called one of the world’s greatest vocal stylists by any number of renowned artists, he is still unaware of his own power and is subject to fits of uncontrollable stage fright that are only dampened, never extinguished, by alcohol. His dependence—because of his own fear of fending for himself and his unwillingness to face the mundane aspects of day-to-day living—on managers, hangers-on, and people with questionable motives has undermined his faith in people to the point where he no longer trusts anybody, friends included. Yet he continues to maintain dependent relationships. He hates to be alone and feels comfortable in the role of big daddy. He can buy cars for people, and he can lend them money—he can give them anything but love.

But the greatest mystery of all is how a man bent beneath a lifetime of personal failure can remain at the pinnacle in his chosen profession. The answer is that there is no one—although there are thousands who try—who can sing like George Jones. His songs are sorrow-tipped arrows that go straight to the heart, and ultimately whether George Jones ever succeeds in mending his ways is of little consideration. What does matter is that he continues to sing in his haunting, untrained howl those mournful songs as only he can.

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Country Music

- East Texas