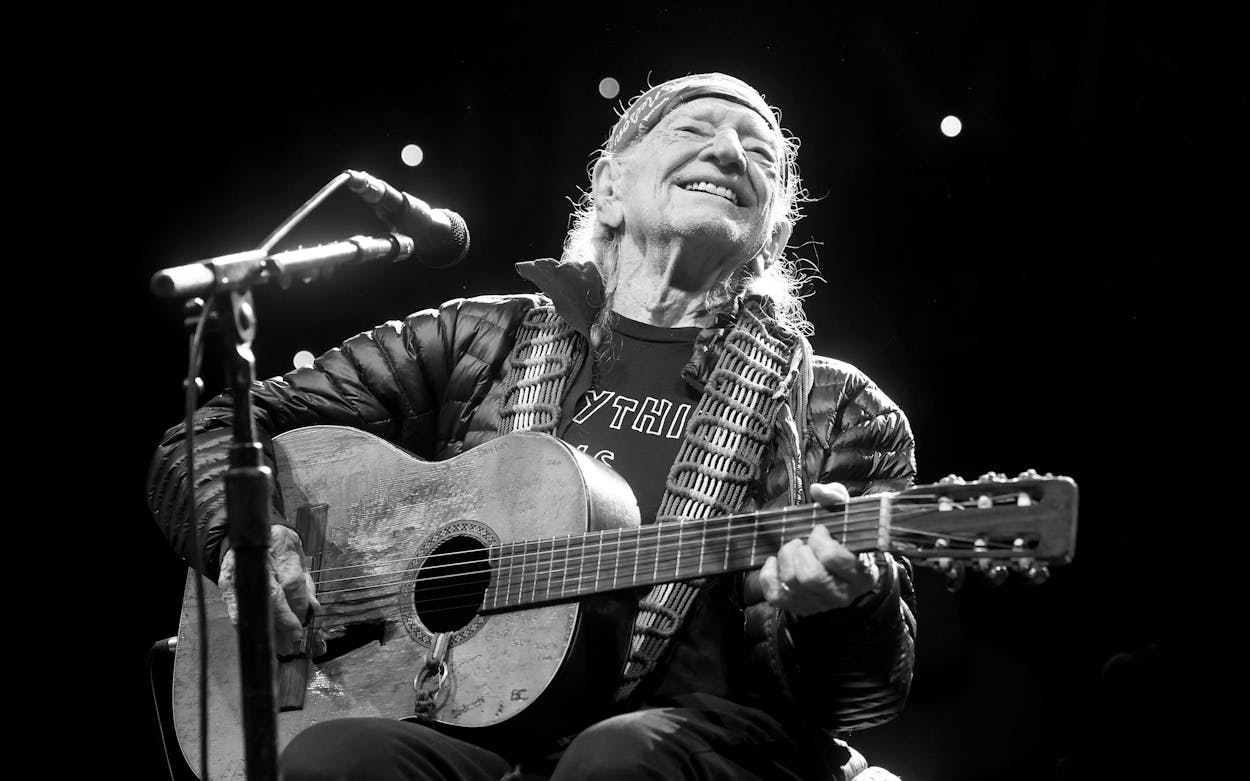

At this point, Willie seems to have outgrown the ability to surprise people. Is he really, at the age of ninety, still touring and playing nearly a hundred shows this year? Will he really release three albums in 2023, an unheard-of pace for an artist even a quarter his age? And is his new record—his 151st, by Texas Monthly’s math—really his first-ever album of bluegrass, a style he’s scarcely even flirted with up until now? The answer to all those questions is, of course, “Absolutely.” He’s Willie Nelson. And anyone still expecting him to pay mind to conventional notions of genre, proper release scheduling, or time itself must’ve missed the last half century of his career.

Inside Willie World, Bluegrass is a record Willie has been threatening to make for years. “Whenever we’ve been about to record,” says Buddy Cannon, Willie’s go-to producer since 2012, “he’d mention maybe doing a bluegrass project. But then we’d find some other songs we wanted to do, and it’d unconsciously get put on the back burner. I can’t even remember who said, ‘Okay, let’s do it now.’” With that green light, the initial plan was to rework old Willie songs with bluegrass pickers and have him sing them as duets with bluegrass vocalists. Cannon pushed back. “There’s a lot of harmony in bluegrass, but there aren’t a lot of duets. And the more I looked at his catalog, the more that felt like a gimmick. These songs deserve better than that.”

Steering clear of contrivances—making a real bluegrass album—was Cannon’s priority, and something of a minefield. Hard-core bluegrass lovers are strikingly possessive of the genre, reflexively dismissive of tourists and dabblers. The closest Willie had ever come to their turf was the T Bone Burnett–produced Country Music, in 2010, in which he was backed by some of the all-star pickers Burnett had assembled for 2000’s hugely successful O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack. “[Willie’s] T Bone record was great,” said Cannon, “but for purists, it had a lot of electricity on it.” Cannon himself is less rigid, but he also remembers being five years old and tagging along with his uncle—whom Cannon says could play any stringed instrument—when he picked under shade trees with local ’grassers in Henderson County, Tennessee. Cannon regards the genre like a first love.

He put together his own supergroup, starting with core members of Alison Krauss’s band, Union Station: bassist Barry Bales, banjo player Ron Block, and multistring virtuoso Dan Tyminski, who stuck to mandolin for Bluegrass. “Those guys love to play,” said Cannon, “and when they aren’t getting paid to play, they just play. And they all love Willie. I’ve never seen people so excited to come make a record. We could’ve run the studio on the adrenaline.”

Cannon chose the songs, anthems like “Bloody Mary Morning,” “Good Hearted Woman,” and “On the Road Again,” but also deep, back-catalog cuts like “Somebody Pick Up My Pieces,” which had previously appeared only on 1998’s Teatro, and “Man With the Blues,” which Willie first cut for D Records in Fort Worth in 1959. Once the sessions started, Cannon would play Willie’s version of a given song for the players and then let them do what they do—namely, place them into timeless, traditional arrangements, with bass and mandolin subbing for a drum kit and a banjo occasionally picked double time under a melody. “A few dyed-in-the-wool purists will say, ‘Willie’s not bluegrass, so I’m not listening,’” said Bales. “But others will look at the credits and say, ‘I know Aubrey Haynie [who plays fiddle] and Rob Ickes [who plays Dobro] . . . and there are no drums on it . . . so I’m giving it a try.’ And nobody can listen and say that we’re calling it bluegrass but it’s not.”

It’s an instantly arresting marriage of sound and songs. “Bluegrass is played a little bit in front of the beat,” said Bales, “and Willie sings behind the beat. So while we’re leaning forward like we’re going off a ski jump, he’s laying back. That builds a little tension and intrigue in there.” Cannon is less technical in his description, summing the style up simply as being “all about the feel.” It’s hard to describe the recordings with much more concrete specificity. Listen and you’ll hear a wry wink in the way Icke’s Dobro opens “Home Motel.” Somehow Tyminski’s mandolin accentuates the smile in the melody to “On the Road Again,” making it shine a little brighter. And the chiming, seven-note guitar run that multi-instrumentalist Bobby Terry plays at the front of “Still Is Still Moving to Me” is so out of the blue it’s almost comical, setting the table for a rendition even more relentless than Willie’s original.

“‘Still Is Still Moving’ is the last song we tracked,” said Cannon. “When I played Willie’s version for the band, they were all in the control room with their pens and charts out, but I was thinking to myself, ‘We’ll never get this thing the way it’s supposed to be.’” When the song ended, he told them he’d changed his mind and wanted to wind down with something else. They protested, persuasively. “In about twenty minutes, we had it cut,” said Cannon. “It was just one of those magical things.”

That’s essentially how the whole process went for the backing tracks, which were recorded over two days in Nashville, every song cut live. The sole overdubbed instrument on the album is Mickey Raphael’s harmonica, which shows up only sporadically and is actually hard to find; it may be a long-standing signature of Willie’s sound, but there’s just not a lot of harp in bluegrass.

The other element Willie fans will likely seek but not hear is Trigger, which doesn’t make even a cameo on the record. Willie’s voice sounds stronger than it has in ten years, and you can hear, in his note choice and phrasing, how much fun he’s having with the new arrangements and melodic shifts brought on by the bluegrass. But the bluegrass style of guitar playing is characterized by flat-picking and fast strumming, which is not what Willie and Trigger do. “When I go down to Austin to get Willie’s vocals, he always brings Trigger in and has him on a guitar stand right beside his mic,” said Cannon. “He’ll sing, then pick him up and start noodling around. On this particular record, Trigger was sitting there, but Willie never touched him.” When they were finished, both men agreed Willie’s guitar would have taken Bluegrass to a different place.

“Willie said this is the first record he hasn’t played Trigger at all since he’s had him,” said Cannon. “I guess he’ll have to play him twice as much on the next one. And he probably will.”

- More About:

- Music

- Country Music

- Willie Nelson

- Austin