The guitar solo in “On the Road Again” begins seventy seconds into the song. You’ve almost certainly heard it, whether or not you paid it any mind. A restatement of the melody on Willie Nelson’s trusty nylon-string Martin acoustic, the solo draws little attention to itself except as a companion piece to the melody, which feels about right.

“It’s just Willie,” says singer-songwriter Norah Jones, a prominent admirer turned occasional collaborator, about moments like this. “It’s an extension of him—his guitar, just like his singing. It makes sense.”

But as with practically everything that has anything to do with Willie Nelson, you’ll find layers of meaning and wonderment beneath that homespun surface. “His ‘On the Road Again’ solo? It’s harder than it sounds,” says guitar ace Jim Campilongo, Jones’s bandmate in a throwback-country act called the Little Willies. “Some of the things he does don’t lay on the fingerboard the way you’d expect. There’s always a few surprises—all these twists and turns.”

Listen again to the solo, and errant details snap into focus. Willie plays the first line of the song’s melody in a square, upright cadence, savoring a hint of dissonance in one passing tone. With his second phrase he relaxes into a swingy syncopation that better suits the tune. He sticks to the melody but with subtle grace notes and quirky phrasing that let you know who’s doing the sticking. It’s just Willie, you might say.

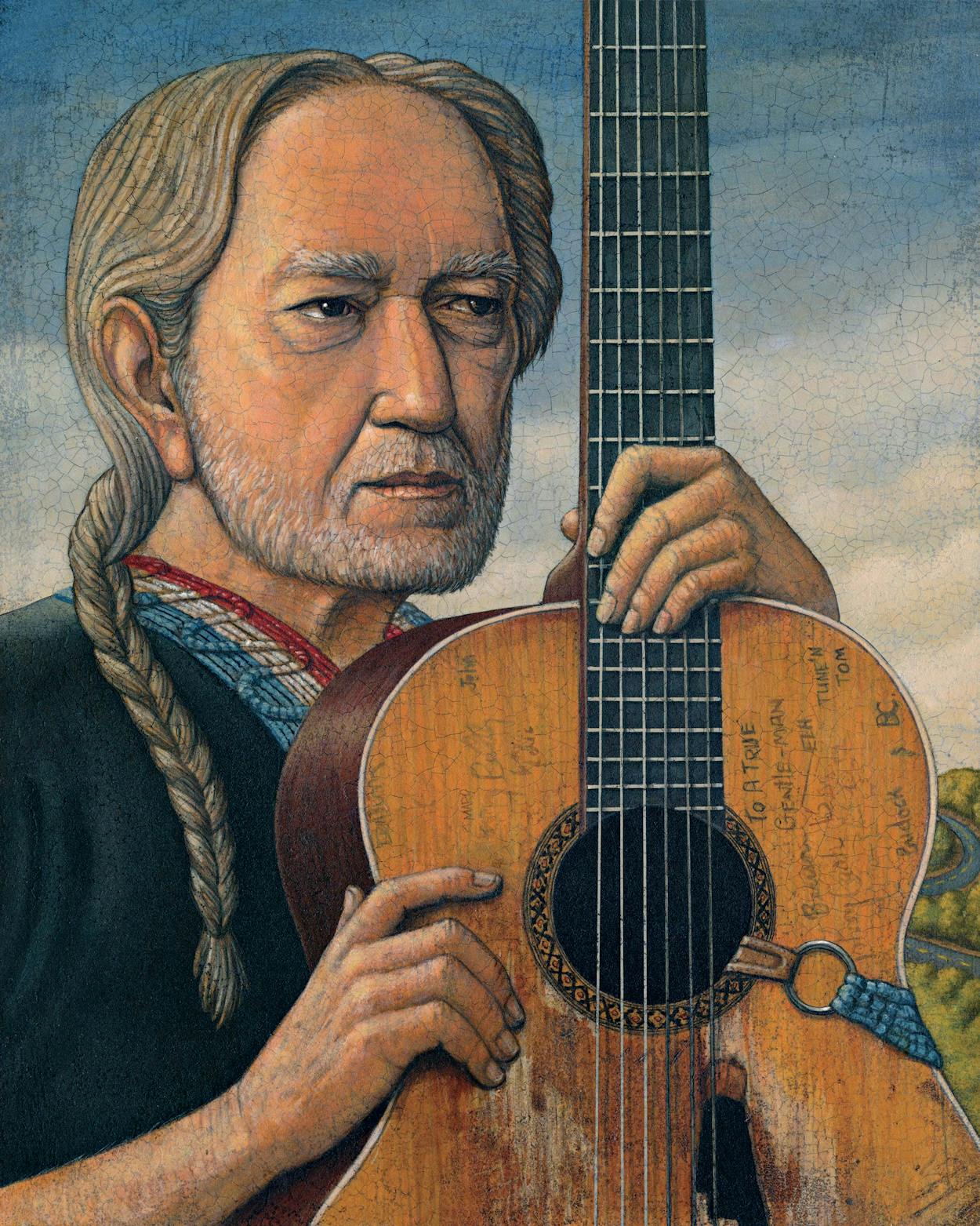

When we say “just Willie,” of course we’re really talking about a tandem. That Martin guitar—a weathered and scuffed N-20 classical model from 1969, custom-fitted with a Baldwin Prismatone pickup—goes by the name of Trigger. This is, by an order of magnitude, the instrument we’ve heard Willie play most often over the last half-century.

“I think when you can play one guitar and get what you need out of it, it’s a relationship just as powerful as your voice,” says blues-rock legend Bonnie Raitt, who has been playing her trademark ax, a Fender Stratocaster widely known as Brownie, for just as long. But Raitt isn’t one to mythologize Trigger as some magical talisman, separate from its owner’s intentions. “Willie breathes as one with his instrument,” she says. “What knocks me out is his beautiful lyricism, and the emotion that he wrenches out of each note.”

On a sad, stoical ballad like his 1980 recording of “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground,” the emotion and phrasing are all of a piece. Willie’s solo strikes a typically elusive balance of understatement and pathos—the sentimentality offset by how hard he picks each note, with downstrokes that suggest the spark of flint against steel. Yet there’s vulnerability in how he finishes those notes, often with a quivery, imploring vibrato.

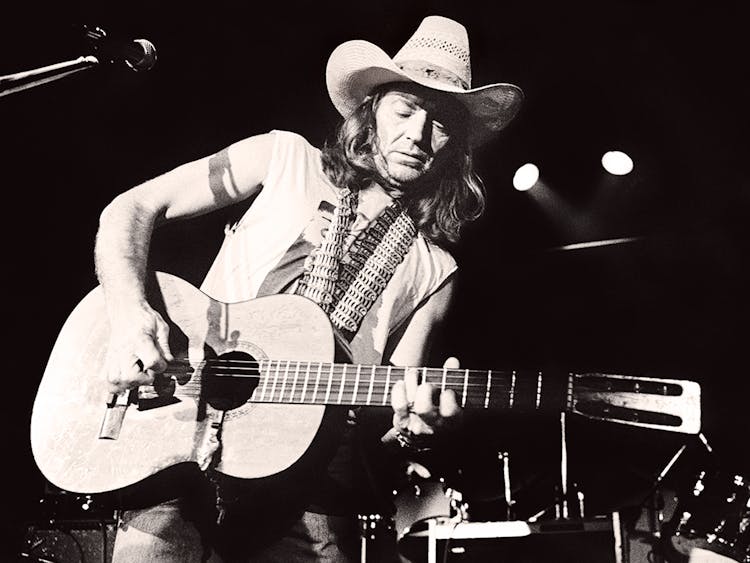

One common way to describe this musical impression is “personal.” A better word might be “personable”—Willie’s playing not only signals who he is, but also makes you feel like you know him. “To me, it’s always mirrored the way he sings,” says Vince Gill, a Country Music Hall of Famer who’s been crossing paths with Willie since Gill was a teenage picker. One of the hallmarks of that singing style is his unruly phrasing—especially the way he elasticizes time, often rushing ahead of the beat like a colt defying his reins. “A lot of people talk about Willie and say, ‘He back phrases,’ ” says Gill, referring to a vocal style that slouches behind the beat. “Which he does—but he also front phrases. And it makes room for him to play. He’s having this call-and-response at all times with the musician in him. It’s just as simple as a conversation.”

If that metaphor calls to mind the example of bluesman B. B. King, so it should—he named the various Gibson semi-hollow bodies he used over the years Lucille and made a trademark out of their anthropomorphic banter. (He once titled an album Lucille Talks Back.) Raitt, who favors this brand of talk-back herself, also uses the term “call-and-response,” with the guitar firmly in response mode, providing commentary. “It’s not an embellishment, it’s an expression of what you’ve just sung, and it takes over,” she explains. “Then when you’ve finished with that phrase and it’s time to sing again, it’s a conversation. And I think B. B. and Willie are the ultimate purveyors of that.”

The blues form a common denominator here—and so, at least on some level, does jazz. “I feel akin to Willie and always have,” Raitt reflects, “because he loves Frank Sinatra and Django Reinhardt as much as he loves Hank Williams and Bob Wills.”

Django Reinhardt was a Romani guitarist whose quicksilver ebullience belied the fact that two fingers on his left hand had been mangled in a caravan fire. During the thirties he perfected a unique fretboard technique using his two good playing fingers, which will seem like an outright miracle if you’ve ever marveled at his zippering arpeggios, as Willie obviously has.

Campilongo once joked that Willie plays like Django if he’d had only one finger. That may suggest a put-down—but Willie has called it the greatest compliment he’s ever received.

He’s never been shy about touting his hero; “Django & Jimmie,” the title track of his 2015 album with Merle Haggard, is only the most literal citation. “I loved the human sound he gave his acoustic guitar,” Willie recalls in his memoir It’s a Long Story. Thirteen chapters later, when he gets around to Trigger’s origin story, there’s a telling echo: “I had the sound I’d been looking for. I heard it as a human sound, a sound close to my own voice.”

Beyond that humanity, Willie derived a degree of musical sophistication from Django, and not just by constantly playing “Nuages,” Django’s impressionistic calling card. “He couldn’t write the songs he writes, with those melodies or those chord structures, without Django and that jazz influence,” says Gill. “He’s way deeper than a three-chord country guy.”

Still, the affinity is most evident in Willie’s guitar playing, especially the way he deals with tension and release. He often employs jazzy chord substitutions, and when faced with a melody that moves from one point to another, he likes to lean on the jangly half-step in between. (For a prime example of this approach, consult the sublime version of “Funny How Time Slips Away” he recorded with Johnny Cash for VH1 Storytellers, from 1998.)

All those cursive little flourishes that prettify a melody, like a vine on a wrought-iron trellis? Also Django. “The way Willie uses slides, slurs, and hammer-ons—that’s all guitar lingo—is similar to how Django Reinhardt would do those things,” Campilongo says.

Willie’s most iconic jazz dalliance is the 1978 album Stardust, but I’ve also seen him perform twice with trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, falling into companionable rapport. Those Jazz at Lincoln Center concerts yielded a pair of albums, Two Men With the Blues and Here We Go Again: Celebrating the Genius of Ray Charles, each one a master class in the deep-river idea of American music.

In his 2019 song “What Comes after Certainty,” the Austin-based singer-songwriter Bill Callahan makes a sly reference to one of Trigger’s more notable characteristics—the thatch of autographs that festoon the instrument’s face. “And I signed Willie’s guitar when he wasn’t lookin’,” goes the line.

In a recent profile, Callahan told Texas Monthly that no, the claim isn’t true, and by email he expanded on the subject. “i would say that willie listens to his guitar very deeply and he is singing to the depth of that listening. there is a palpable electricity of feeling between the two, like he owes something to his guitar, it’s a relationship. his guitar is the sound of the honor he pays it. but you get a sense that it’s a two way street—that trigger would get lonely without willie. in a willie instrumental song, i don’t miss his voice because it is still there, in the guitar.”

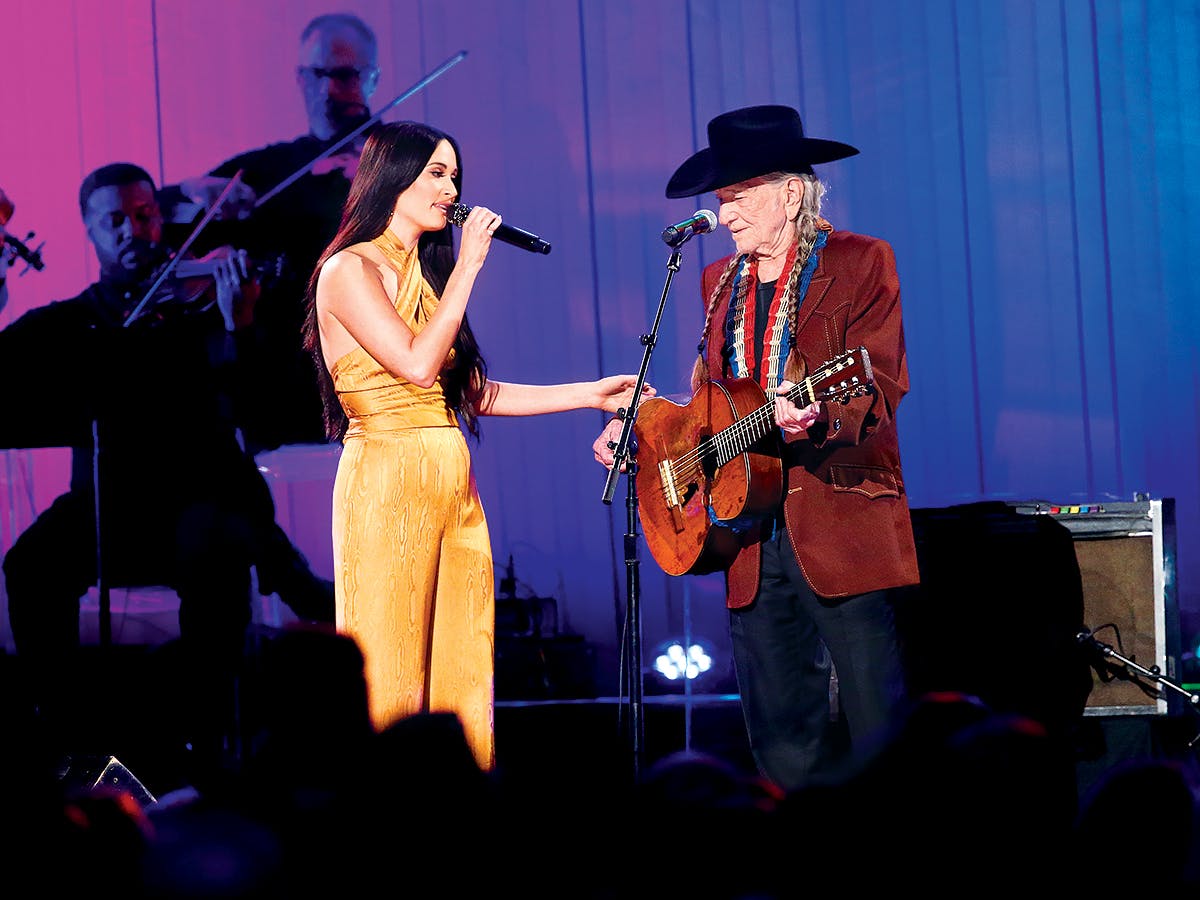

The prospect of missing Willie’s voice has become a more tangible concern lately. Perhaps you saw him on the 2019 CMA Awards, struggling to get through “Rainbow Connection.” He cradles Trigger as if holding on to a lifeline, fingers fluttering without striking a note. When Kacey Musgraves walks out to join him in a duet, the sweetness and smoothness of her tone feel like a reassuring salve. “It was one of the most poignant things I’ve ever seen on TV,” says Gill.

A few years ago, when Willie canceled a run of tour dates due to illness, I worried about whether I’d see him in concert again. But he kept his 2017 engagement at the Mid-Hudson Civic Center, a couple of hours north of New York City.

Willie was in fine, rambunctious form, urging Trigger into action from the opening bars of “Whiskey River.” Later there came a fondly meandering “On the Road Again,” with a solo that weighed puckish hesitation against antic strumming. This was followed by an exquisitely sensitive “Always on My Mind,” with Willie transforming an eight-bar break into a pocket concerto, a small feast of fleeting dissonance and offhanded flourish.

Who else sounds like this? I asked myself then, as I often do when contemplating Willie on guitar. The answer is obvious but worth saying anyway: Nobody does. It’s just Willie.

Nate Chinen is a former music critic at the New York Times and the author of Playing Changes: Jazz for the New Century.

This article originally appeared in the Willie Nelson special issue with the headline “Willie Nelson, Guitarist.” Subscribe today.

More Essays About the Red Headed Stranger:

Willie Nelson, the People’s Champion

Willie Nelson, Interpreter of the Great American Songbook

- More About:

- Music

- Willie Nelson