This story originally appeared in the November 2017 issue with the headline “A Pioneering Pitmaster.”

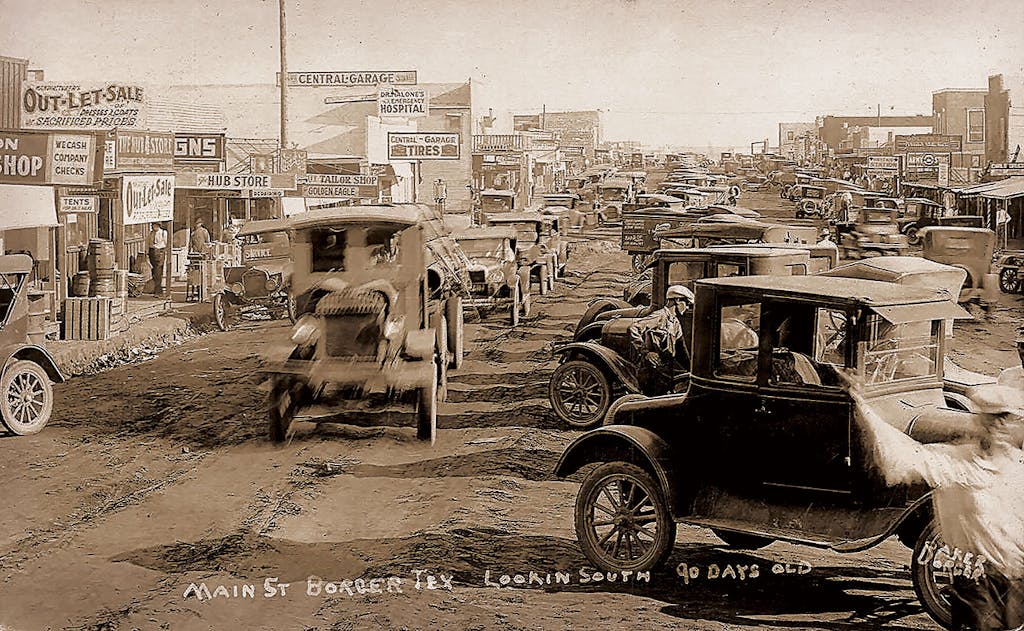

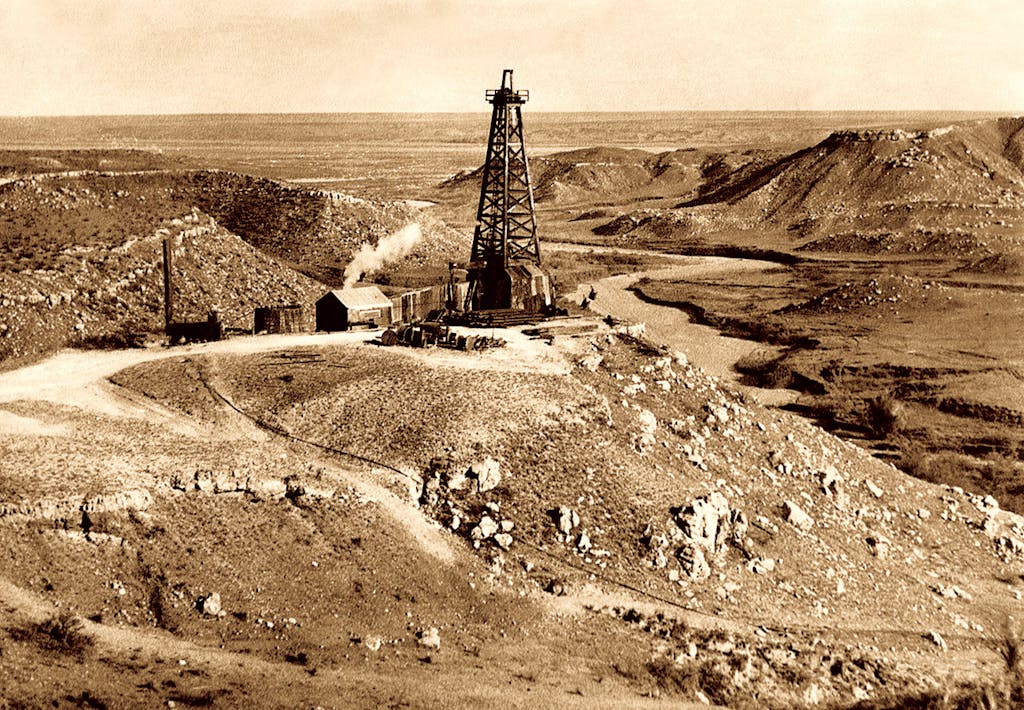

The dusty patch of land that would become Borger, Texas, wasn’t much more than a raucous encampment of oil prospectors when Etta Randall, a 29-year-old divorcée with an 8-year-old daughter in tow, traveled 450 miles from Mineola to make a new life for herself there. Forty-five years later she’d tell a reporter from the Amarillo Daily News: “When I first came, in 1926, there weren’t any buildings, any wooden houses. Everywhere you looked, all you could see were tents, hundreds of them.” Given her bleak description of the place, she likely arrived around the time A. P. “Ace” Borger, a Missouri-born land speculator capitalizing on the nascent Panhandle oil boom, acquired 240 acres of land and began to sell plots for his namesake town. In newspaper ads, the Borger Townsite Company made big promises, like oil riches, and smaller ones, like actual buildings and houses. By the end of the year, the population of what had come to be known as Tent City had swelled from a few hardy souls to an estimated 45,000, all lured by dreams of hitting it big.

It’s not clear what possessed Etta to move to Borger; in a collected history of Hutchinson County, her eldest daughter, Lillar George, would say only, “Times were hard for the black folks of Borger, but not as hard as they were at Mineola.” Maybe it was poverty or her failed marriage that motivated the move. More likely it was an escape from a place where the Second Ku Klux Klan was on the rise and racism was so deeply entrenched that her congressman, Morgan G. Sanders, campaigned against an anti-lynching law. Perhaps the limitless possibility of starting from scratch appealed to Etta, the idea that she could leave all that behind and find her footing in a town that was doing the same.

To start, Etta ran a laundry service, as she had in Mineola. Later she found a job at a hotel, and then she met her second husband, S. E. White, a carpenter at the Rex Theatre, on Main Street, which by that point was bustling enough to be known locally as the White Way. Together they worked and raised her daughter Lavata, socking away money in the dirt, literally. “My husband and I would take our daily earnings, put them in a big tin can, and bury them in the ground inside the tent,” she recalled. By 1934 they had saved up enough to open their own business, a barbecue joint on North McGee Street, just off Main. They called it White Way Bar-B-Q, but everyone who remembers it now called it Etta’s. Indeed, advertisements for Etta White’s Barbecue Stand started to appear in the Borger Daily Herald in 1938. She and S.E. ran the place with the help of Lavata and Lillar, who had followed her mother and sister to Borger a few years earlier. But there doesn’t seem to be any doubt as to who was in charge: “Mother attended to the cooking and fire,” Lillar recalled. “White Way Barbecue” finally made it into Borger’s printed business directory in 1941, with a “(C)” next to the name to denote a “colored” business (that indignity disappeared with the 1946 version). Etta would add “Southern style fried chicken” to her menu a few years later, but it was her beef that proved most memorable.

“If you wanted barbecue, that’s where you went,” says Cleo Morrison, who moved with her family to Borger in 1944, when she was twelve years old, and who now volunteers at the Hutchinson County Historical Museum. “She served beef and ribs, coleslaw, beans, and her own special barbecue sauce,” she says, but it was Etta’s unusual style of beef that everyone came for (and, for Morrison, the pinto beans: “I was there one day when she was fixing to season them. She added a big spoon of Crisco and some salt”). In an old concrete pit outside, behind a four-table dining room Morrison remembers as spotlessly clean—“She had about scrubbed the design off the floor”—Etta cooked hundreds of pounds of shoulder clod (instead of the more traditional brisket), smoking the whole thing for hours, cutting it into bite-size cubes, covering it in sauce, and then cooking it a little more. This made for tender, highly seasoned chunks of meat reminiscent of our modern-day burnt ends and distinct from the sliced and chopped brisket common throughout the rest of the state. It’s a style of barbecue cookery uncommon then and now. But there’s one restaurant that continues to serve beef in the same way: Borger’s own Sutphen’s Bar-B-Q, which opened in 1950 in nearby Phillips and moved to Borger in 1964. It’s doubtful the similarity is a coincidence. Joey Sutphen, the former owner and the son of the founders, Joe and Marjorie, said he wasn’t sure of the origin of the family’s style, but he did acknowledge that Etta was in Borger “for a long time.”

Her longevity was indeed remarkable, in that she not only survived but thrived in a lawless boomtown that burned to the ground twice in twelve months and whose first sermon was delivered, according to a June 11, 1926, headline in the Crosbyton Review, “from [a] beer keg in [a] domino parlor.” No doubt she watched Borger become a haven for bootleggers, gamblers, and gangsters, a turn of events that prompted the Fort Worth Star-Telegram to label it the “Sodom of the Panhandle” in June 1926. She certainly would have been affected by the 1929 murder of District Attorney John A. Holmes (appointed by the governor “to relentlessly prosecute criminals who infested oil fields during Borger’s boom years”), the subsequent imposition of martial law, and the arrival of a contingent of Texas Rangers, who arrested a dozen people on narcotics charges on their first day. They found the town so in need of legitimate law enforcement that they opened a temporary headquarters there. Borger was a rough place for anyone, especially a young black woman. Ace Borger himself was shot to death at the post office in 1934 by the county treasurer.

A “big, jolly person,” in Morrison’s words, Etta served four generations of Panhandle residents, an eternity in the fickle world of restaurants, much less barbecue joints. And she clearly made a good living doing so. “Back in the early seventies,” Morrison says, “she went out to the Cadillac dealer here in Borger. She was gonna buy a car. She was milling around and looking and trying to get the salesman’s attention. He just ignored her. Etta left and went to Amarillo to buy her Cadillac. When she went to the desk to pay for it, she counted out $100 bills and bought it in cash. The guy in Amarillo called over to the dealer in Borger and said, ‘You need to pay attention to your customers. This one paid cash.’ ”

It took a heart attack to make Etta close her restaurant, in 1972, one year after she told that Amarillo Daily News reporter that she had no plans to retire. She died two years later. She had survived divorce and the premature deaths of loved ones (Lavata at forty and Lillar’s two children, both of whom drowned soon after they’d arrived in Borger). She’d turned her back on unfortunate circumstances, made it through the early days of an anarchic and dangerous oil town, and pioneered a distinct style of barbecue that lives on to this day in the Panhandle.

- More About:

- Black BBQ