Barbecue and squabbling go hand in hand. Arguing why my favorite place is better than yours is a sport (sometimes we at Texas Monthly act as referees), and barbecue families can be some of the fiercest competitors. In Lockhart, the departure of Kreuz Market in 1999 from the building that now houses Smitty’s may be the state’s most famous barbecue split. The Black family of Black’s BBQ in Lockhart had a spat before opening Terry Black’s Barbecue in Austin in 2014. And let’s not forget the couple of months in 2013 when two barbecue joints in Rockport both claimed to be the true Top 50 barbecue joint in town. This kind of infighting goes way back: more than a century ago, an El Paso dispute became what was probably the first Texas barbecue rivalry to end up in court.

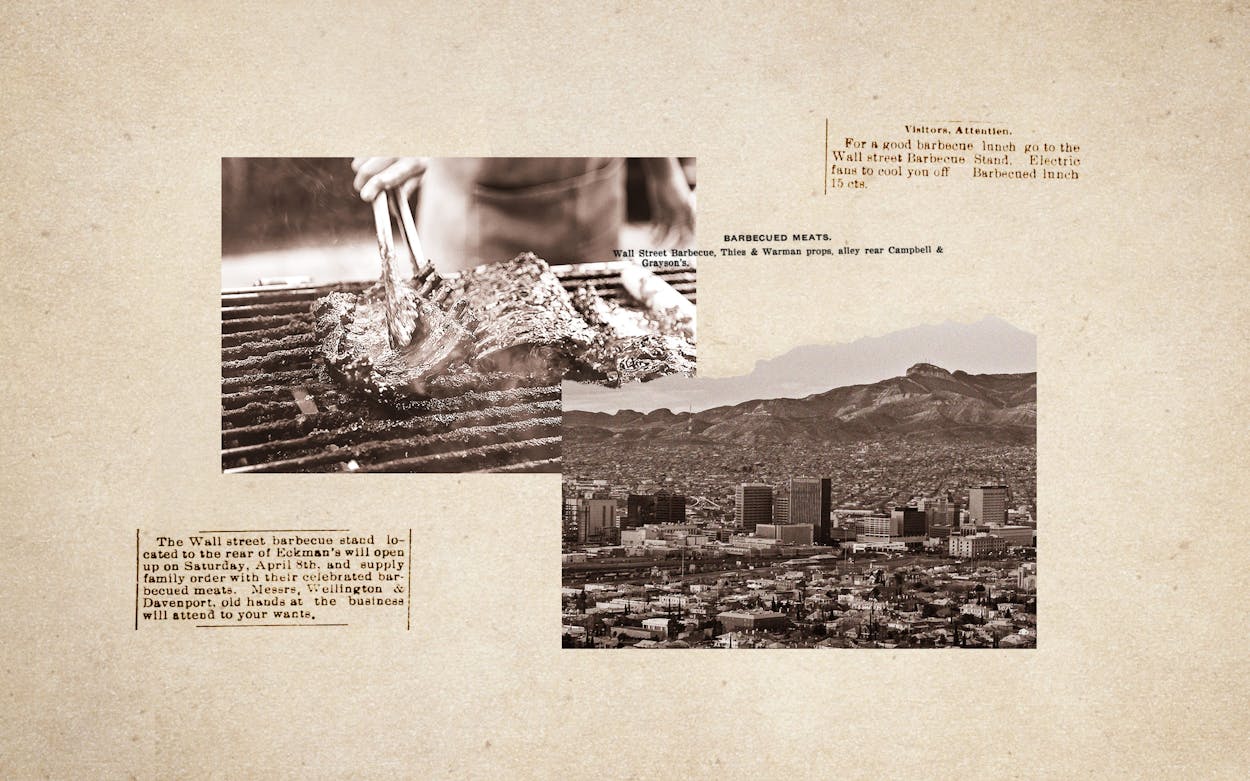

El Paso played an early role in Texas barbecue history. Lockhart and Elgin in Central Texas might get all the credit today, thanks to the longevity of Kreuz Market and Southside Market, but grill masters smoked plenty of meat out in West Texas too. The WAD Market in El Paso advertised “meats and fowls barbecued to order” as early as 1893, and the first recorded mention of smoked brisket for sale in Texas was from Watson’s Grocery in 1910. Just a few years earlier, the city witnessed a tussle between the established Wall Street Barbecue and upstart Pioneer Barbecue.

Henry “Pap” Davenport opened Wall Street Barbecue on April 8, 1899, in an adobe building in a back alley, a half block off busy San Antonio Street. Davenport, a Civil War veteran from Arkansas, had moved to El Paso to work as a cattle driver before opening his own restaurant at age 62. As a restaurant dedicated to serving barbecue, Wall Street was a rarity in Texas; at the time, most barbecue businesses were primarily meat markets.

Davenport was a savvy businessman. The El Paso International Daily Times praised him as a “champion barbecuer of the southwest” while reporting on the “fine barbecue meats and corn and light bread” he had provided to its staff two months after opening. After a competitor opened a few blocks away, he again sent lunch to the Times, and the El Paso Herald received “venison, beef, and beef’s heart, cooked in a manner that would temp the most fastidious appetite.” The competitor was already out of business by the time Davenport catered the fireman’s ball in November, and the Herald gushed that “the barbecue on Wall Street knows how to prepare a meal fit for Persian kings.”

Even with the good press, Davenport headed south to Mexico, along the Sierra Madre rail line, looking for gold. He sold Wall Street Barbecue to George H. Cranston, who installed electric fans in the restaurant and advertised fifteen-cent barbecue lunches in the Times in June of 1900. In October of that year, Cranston advertised that his restaurant was “strictly American” and didn’t allow Chinese diners. The 1901 the Worley’s El Paso directory listed twenty-six restaurants, two of which are listed as “strictly American” while eleven were Chinese-owned, including American Kitchen. Wall Street Barbecue wasn’t listed that year, but was the only restaurant listed under the new “Barbecued Meats” section in the Buck’s El Paso directory of 1902.

Cranston died on the county poor farm, a sort of working farm for the poor and destitute, in late 1902, and Wall Street Barbecue had yet another owner, Carl Theis (sometimes spelled Thies). It’s unclear when Theis moved the business from the alley (which was behind what is now SK Cosmetics Beauty Supply at 210 East San Antonio Avenue) to its new location at 414 Mesa Street, but the original building is not included in El Paso’s 1905 map from the Sanborn insurance company. In 1907, Theis had tired of Wall Street Barbecue, and sold the new location to Henry Ballard and Joseph Franklin, who thought they’d be the only barbecue game in town. “Do you like barbecued meats?” they asked in a June 1907 newspaper ad. They were about to be double-crossed.

“You have met us before,” the ad promised for Pioneer Barbecue. The owner was one Christine Theis, Carl’s wife, and Pioneer Barbecue opened its doors two blocks from Wall Street Barbecue two months after the new owners took over. Ballard and Franklin were furious. They claimed that Christine was listed as the operator of Pioneer Barbecue because Carl had signed what amounted to a non-compete contract when he sold them Wall Street Barbecue. “It is alleged that when the plaintiffs purchased the place of business from the defendants that the contract was made that they would not go into the same line of business again,” read an El Paso Herald report from the court proceedings on October 12, 1907. Two days later, Judge Goggin sided with Carl and Christine Theis. They would not be forced to shut down Pioneer Barbecue.

That was more than a century ago, and even today I don’t know of a successfully defended non-compete clause in Texas barbecue. This may have been the first mention of one. Pioneer Barbecue kept advertising, offering free delivery for orders costing more than a quarter, and claiming to be the only barbecue joint in town offering pork, lamb, and beef. Ballard and Franklin, however, got the last laugh. Carl Theis took out a want ad looking for a job as a camp cook in late 1909, just eighteen months after opening Pioneer Barbecue. Ballard continued to operate Wall Street Barbecue until 1918, aside from a brief break in 1914 to deal with a case of “the grip,” or influenza. It was quite a run in a time when most of the barbecue joints mentioned in newspaper ads and city directories lasted just a year or two.

A newspaper ad offered for sale “the oldest barbecue place in town,” cheap, in 1918. The building at 414 Mesa soon ended its run as a barbecue joint and became an auto service offering chauffeured cars. Today the location of the barbecue joint would align with the parking garage entrance off Mesa into One San Jacinto Plaza. Henry Ballard retired, then died at age 81 in 1931, the same year his grandson Conger Ballard Jr. was born. Conger became a successful pop songwriter, and Linda Ronstadt famously performed one of his songs, “You’re No Good.” If only his grandfather could have played that tune for the folks who got away with breaking Texas barbecue’s first non-compete clause.

- More About:

- El Paso