Last year, I bought a whole beef carcass for the first time. I was helping with a barbecue event where the main attraction was the full steer cooked over wood in a pit built with concrete blocks. The price quoted from Cameron’s 44 Farms—known for its quality Angus cattle—for the entire steer was $4.25 per pound. At the time that was more than what most pitmasters were paying for Prime grade brisket, but a lot less than tenderloin. The steer arrived in eight large pieces, stacked onto a wooden pallet and surrounded by cardboard. We cooked those large pieces, what butchers call subprimals, in their entirety, then trimmed the fat and separated meat from bone for serving. Depending on their spot in line, guests ate from the chuck, or the round, or anywhere in between. The whole animal, minus the head (which wasn’t included), was consumed, and I didn’t hear any complaints.

Last month, La Barbecue in Austin paid $7.52 per pound for Prime brisket. That’s high even compared with the rest of the current market. Although beef prices across the board have come down since then, it’s safe to say that prices for the beef cuts used for Texas barbecue—beef ribs, brisket, shoulder clod—rose significantly in the last few months. At the same time, the value of live cattle is still recovering after plummeting in May. Both of those issues were because of the bottlenecks at beef processing plants across the country that have been shut down or had their output throttled by alarming rates of COVID-19 spread among their workforces. Although some joints are absorbing the costs, many have had to raise menu prices or have simply tried to persuade customers to order barbecue that’s not brisket.

This price hike has made me think back to that whole cow I ordered. What if a barbecue joint could get the beef it needs without being dependent on the national supply chain? Is it possible? To find out, I talked with Clinton Burns, the owner of Smithville Food Lockers, about how a restaurant could use a small-scale beef processor such as itself to keep its smokers full of beef, pandemic or no. Smithville Food Lockers is inspected by the state of Texas’s Meat Safety Assurance Unit rather than the USDA. State-inspected facilities (if you’re curious, here’s a full list) aren’t allowed to sell the meat they process beyond state lines. Although they are allowed to sell to Texas restaurants, they have few restaurant clients because they mainly deal in whole and half carcasses. They might offer some individual cuts and sausages at a small retail counter, but they don’t have the capacity to send a few hundred briskets to a barbecue joint every week. In other words, if a joint used a small processing plant like Smithville Food Lockers, they’d need to redesign their menu to use more of the steer, preferably the whole thing.

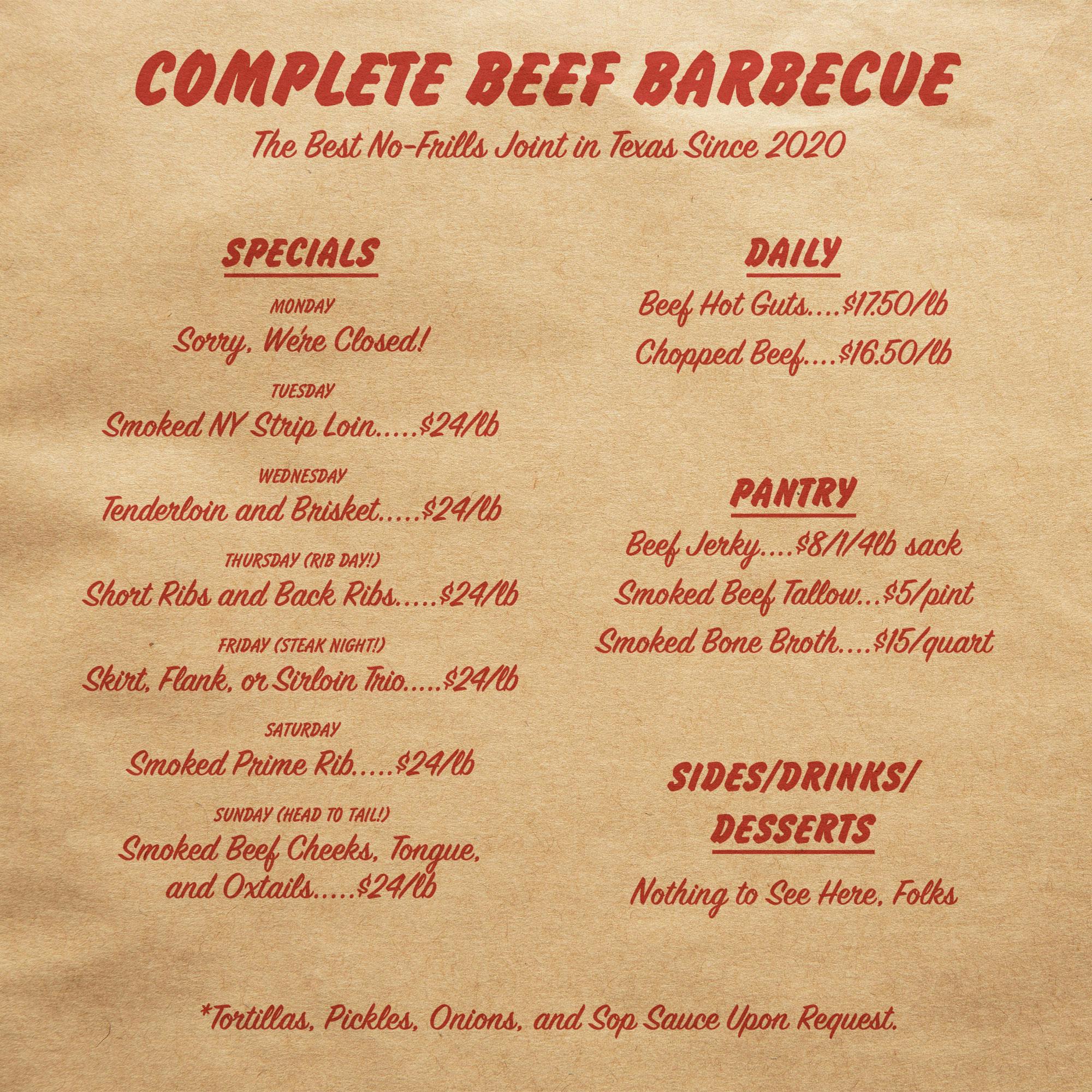

To give an idea of what that might look like, I set out to create a fictitious menu for a barbecue joint that I’m calling Complete Beef Barbecue.

For this endeavor, I needed to find out how much meat a joint needs for a typical week, so I turned to another expert: pitmaster Bryan Bracewell, of Southside Market. He told me that the Elgin location uses an average of 11,500 pounds of raw meat every week; of that, 4,600 pounds is made into their famous hot gut sausages. I looked at how to use a full steer to match that level of barbecue output.

So how much barbecue is in a whole steer carcass? Using the Beef Cutout Calculator, I created a spreadsheet (we’ve uploaded it here if you’d like to take a look) of all the beef cuts and then used USDA data on cooking yields to determine how much barbecue would result. The short answer is that a 1,250-pound live steer will result in about 427 pounds of cooked barbecue. To produce the same amount of barbecue as Southside Market, Complete Beef Barbecue would require twenty head of cattle per week. The big difference is that with just forty briskets per week, it couldn’t be a daily offering.

Complete Beef Barbecue is built on a foundation of smoked sausage and chopped barbecue. The chopped barbecue comes from several different cuts like the shoulder clod, the gooseneck, and the chuck. All the trimmings and fat are to be used for sausage. Other more prized cuts are offered as daily specials. Seven days’ worth of boneless strip loins are smoked for Tuesdays, tenderloins and briskets join forces on Wednesday, Thursday is beef rib day, and the Prime ribs are smoked and sliced on Saturday. The steaks that aren’t as familiar as strips and ribeyes— like flanks, skirts, and tri-tip—make up the options for Friday’s steak special, and Sunday is reserved for beef cheek barbacoa, smoked beef tongue, and oxtails.

The concept might sound foreign to barbecue diners used to ordering smoked brisket anytime they’d like, but meat market barbecue in Texas was built on using the whole animal. Many old-school pitmasters remember cooking a whole lot more of the steer than what we eat at barbecue joints today. Joe Capello, of City Market in Luling, said it used to get whole steers delivered when it was still a functioning market that sold raw beef. “The hindquarters were cut up for the meat counter—the rounds and the T-bones. The forequarter was cut up to barbecue—the brisket, the short ribs, and the shoulder clod,” he said. Allen Prine, of Prine’s BBQ in Wichita Falls, said they brought in whole forequarters in the eighties. “We’d cut these big 110-pound pieces into about eleven different shaped pieces,” he said, adding, “We cooked them all exactly like we do the briskets now.”

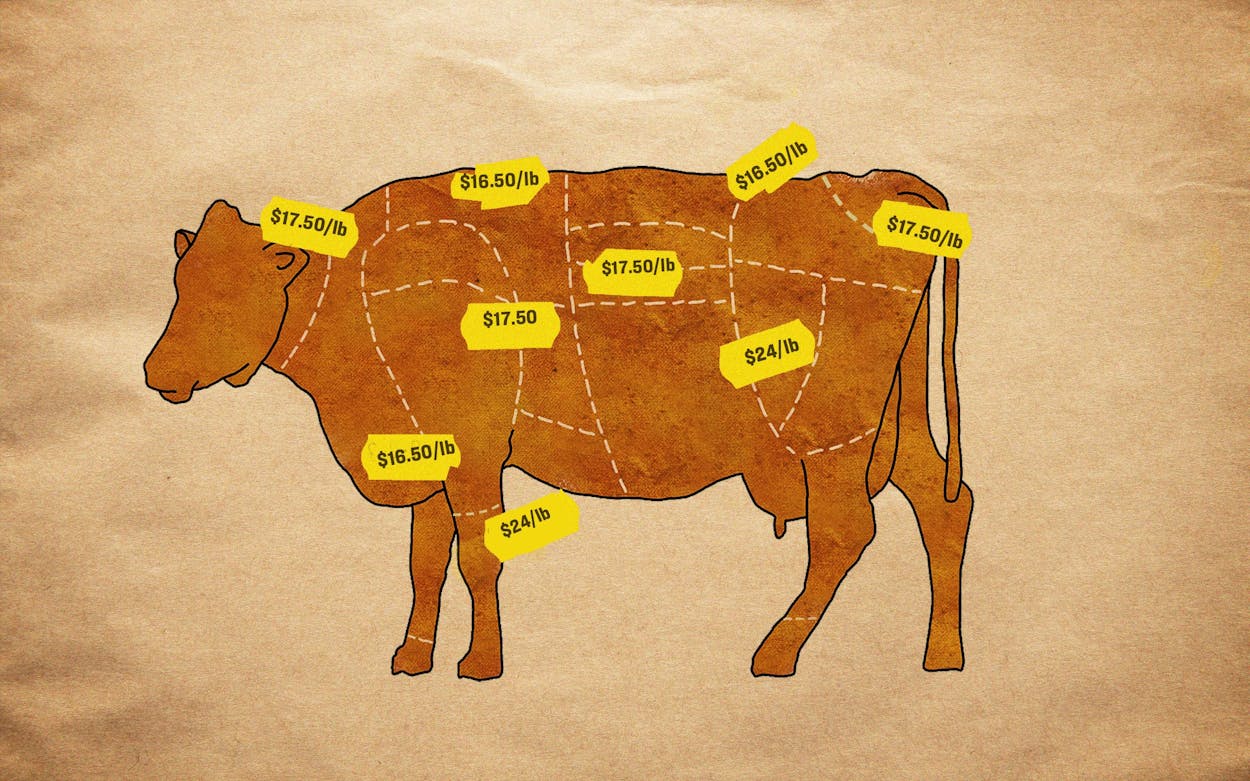

Getting those whole steers delivered would require a relationship with a rancher or a small slaughterhouse that can provide its own cattle for processing. Burns, at Smithville Food Lockers, said the standard price for a steer from his brother-in-law’s ranch to be fully processed into steaks and sausages would be $5.50 per pound for a whole carcass. At 44 Farms, the price is still $4.25 per pound for a whole steer cut into subprimals. Complete Beef Barbecue would require processing somewhere in the middle as well as a steady volume of twenty head per week, so I’ve assumed a price per pound of $4.75.

Complete Beef Barbecue would operate as a sort of barbecue market. There wouldn’t be any sides or drinks, and definitely not pork or chicken. Because of that, the revenue wouldn’t get the benefit of those cheap add-ons that usually boost restaurant profit margins. Still, a full menu of reasonably priced barbecue would mean a food cost around 40 percent of gross revenu, which isn’t out of the ordinary for full-service barbecue joints. It would be mostly a walk-up joint, with a few picnic tables. On request, it would offer tortillas, pickles, onions, and “sop sauce,” which I’ve seen on old menus, referring to the liquid used to mop the meat with during cooking.

As brisket prices come back down from the stratosphere, barbecue joints might even be getting more comfortable returning to their previous business models, but that doesn’t mean we should be comfortable returning to business as usual. Many of the meat plants are operating despite their workers continuing to contract the coronavirus at alarming rates. The meat supply system just experienced the biggest shock most of us have seen in our lifetime as a result of COVID-19. Beef processing capacity has experienced a rebound since the depths of the coronavirus-related shutdowns, but the virus hasn’t gone anywhere. With the alarming increase in new cases of late, a repeat of the volatility we just witnessed isn’t out of the question.

Now might be the time to reconsider the model for modern Texas barbecue. Instead of relying on the massive beef companies to provide boxes of briskets, maybe cutting out the middleman by using smaller slaughterhouses to process locally raised cattle is a path forward, even if it means smoked brisket just once a week. Maybe Texas is ready for Complete Beef Barbecue.

- More About:

- Smithville