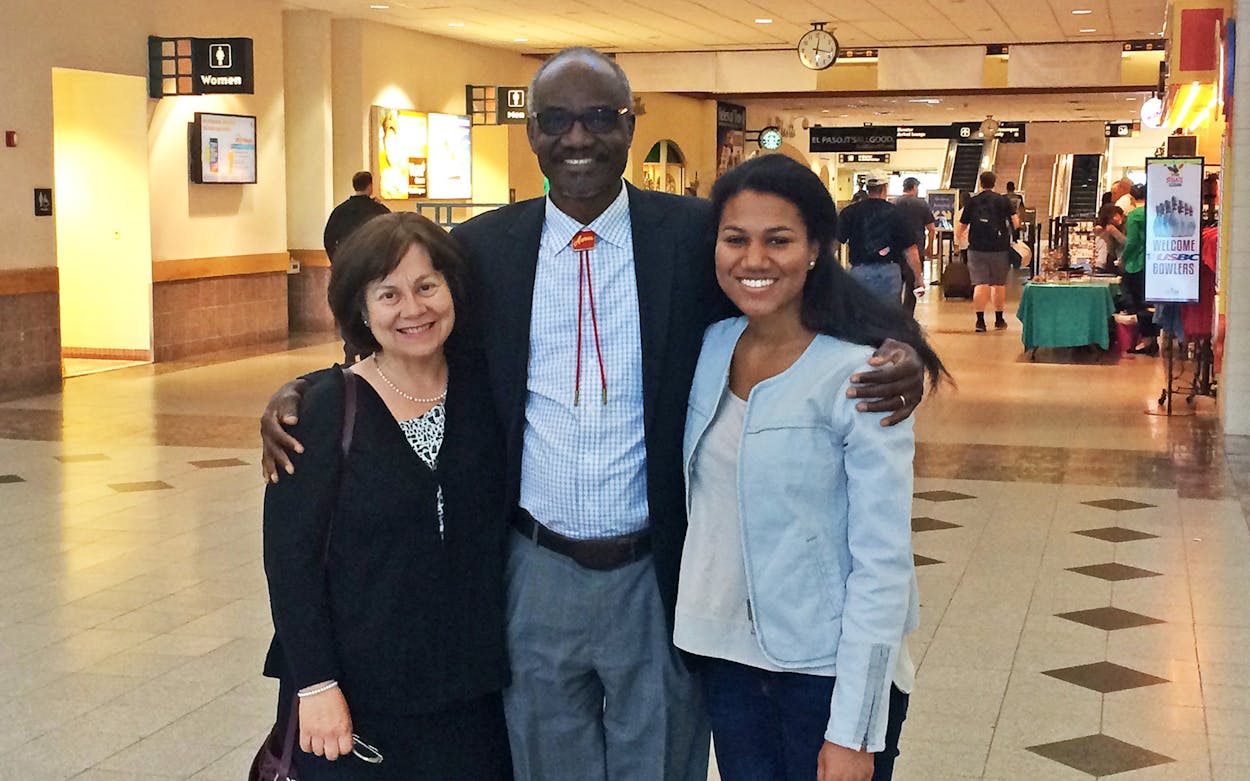

On a blisteringly hot mid-July day nearly thirty years ago, as my parents walked down the jet bridge at the El Paso International Airport, they heard the faint notes of a mariachi tune playing in the distance. After rounding the corner of the walkway and stepping into the terminal, the two stumbled upon the source of the music: fifteen of my mother’s friends and colleagues had gathered, some with instruments, to welcome my African father to the United States—a country he had never visited but had agreed to call home after marrying my American mother abroad. With a freshly pressed permanent resident stamp in his passport, my father readily embraced a new title that day. It was one that my mother had taken on just nine years before him, and one that I would acquire by birth a year and a half later: El Pasoan.

“I thought that was the best day of my life,” my father recently told me. “From that first hour at the airport, I found myself in a place where I could live and enjoy the people around me.” After fleeing the conflict-riddled nation of Chad in the early eighties, he saw El Paso as the promise of a new beginning for him.

For someone who now identifies strongly as an El Pasoan, I spent the better part of the first two decades of my life somewhat baffled by my family’s existence there. In a border city where the census estimates that more than 80 percent of the population identifies as Hispanic or Latino, and just under 4 percent identifies as Black or African American, my family—a tall, lanky African, a white woman with the slight hint of a Georgia drawl, and an immensely bushy-haired kid—was an unusual sight. Like many El Pasoans, we’re bilingual. But instead of Spanish, our romance language of circumstance is French. (My mom is quite capable with her Spanish, though, and defiantly says that people who are bothered by the language’s prominence in the city should probably get out of town.) Unlike other cities in Texas where African immigrants have established substantial enclaves, El Paso is not the most obvious place for a family like mine to plant its roots. And yet there’s no other place we’d rather call home.

During the past few months—as I’ve been living in my current home of New York City, once the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States—the concept of home has been weighing heavily on me. Now as I sit in my apartment in Brooklyn for days on end, I think of morning walks in the foothills of the mountains in the Chihuahuan Desert. As I push my way through a crowded bodega-like grocery store, I dream of mole enchiladas and honey-filled sopaipillas at L&J Cafe. Bouncing along to the soca and calypso music my neighbors blast on the steps of their brownstones, I think of the banda and ranchera music drifting from the backyards of neighbors in El Paso.

Living in Brooklyn is the most recent stage of an introspective journey to better understand both what it means to be sub-Saharan African and a Black person in America outside of the isolation of my hometown. My college years took me to the frigid shores of Lake Michigan, the Brittany region of France, and the West Campus neighborhood near the University of Texas at Austin. Since graduation, I’ve lived in a landmark neighborhood in Washington, D.C., a crumbling apartment with a perfect hammock overlooking a lagoon in francophone West Africa, and now in a historically Black and unnervingly gentrifying neighborhood in New York City. Each move has represented another step forward in my interrogation of my racial and cultural identity, but every step has also been a reminder of how deeply El Pasoan I am.

My mother was my age, twenty-seven, when she first moved to El Paso, albeit reluctantly. Raised in a swampy, lush part of the East Coast, she was wary of the seemingly harsh climate of the Southwest that she recalled from a cross-country road trip from Atlanta to Northern California in her childhood. She remembers Yuma back then as “one of the hottest places,” and to her, the wide-open spaces that Texans have romanticized for centuries seemed like “the beginning of nothing.”

She was working abroad when an organization in El Paso first recruited her to work for them, but she declined the offer, uncertain about her career trajectory. A couple years later, she was living near her parents in Northern Virginia when she received the job offer again, so she relented and visited El Paso. Though she was pleasantly surprised with what she found there (her future coworkers were especially kind, and the desert in November wasn’t all that bad), the decision to stay, by her telling, took a couple of nudges from up above.

First, there was the time she turned on her car in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., and Marty Robbins’s buttery voice filled the vehicle with the lyrics of “El Paso,” a song she had never heard until that moment. Later, when she was at a discount clothing store in Virginia looking for new jeans, the only pair that fit perfectly was labeled “El Paso Jeans: Made in El Paso, Texas.” (The pants are long gone, but the cut-out label is still on display via a thumbtack in our house.) Finally, she had prayed for a sign that she shouldn’t go, but one never appeared. So she and her mother packed up her tiny Toyota Corolla and made another cross-country road trip, this time so that she could start a new life out in the West Texas town of El Paso. She assumed her stint there would last only a couple of years, but she hadn’t yet experienced what she now points to as what makes El Paso special: its sense of “cariño,” a Spanish term describing affection and care.

“This culture is so open to loving you,” she says, citing El Paso’s Mexican influence, which seems to envelop everyone around it in kindness. She’s come to adore the Chihuahuan Desert landscape, and when we talk on the phone, she often reports on the blooming status of native and naturalized plants in the neighborhood. In the spring, the bird of paradise attracts butterflies and hummingbirds, and the sweet acacia trees sprout yellow flowers before giving way to green leaves that provide respite from the scorching sun. She can’t resist stopping to smell the light fragrance of the Chihuahuan sage, the shrub whose spearlike branches sprout purple blooms in the summer.

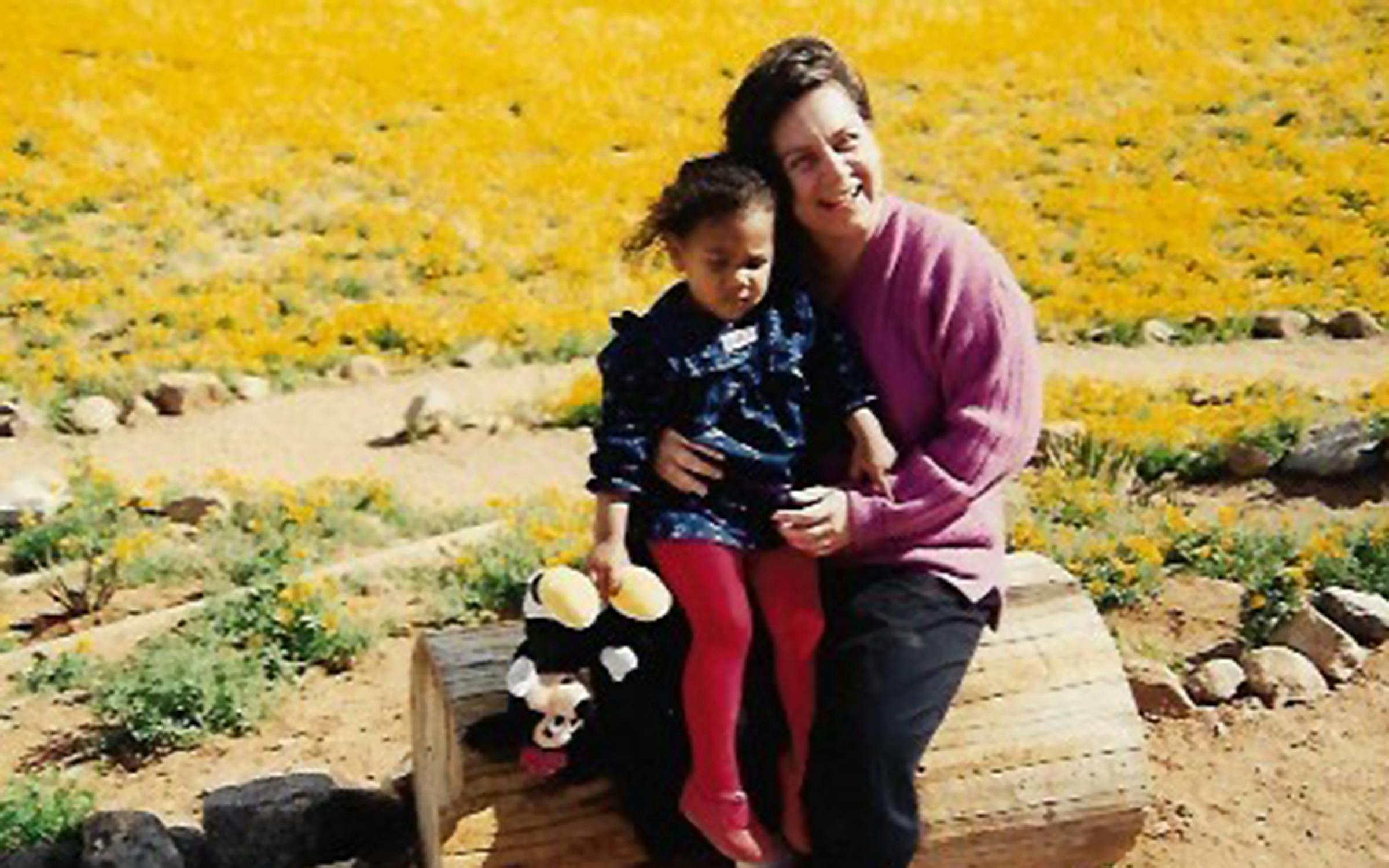

My father feels similarly about the El Paso community’s warmth, although for him, it’s even more personal. “It looks exactly like my culture,” he mused one recent evening. He points to the large family gatherings we often saw in public parks for birthday parties and on Mother’s Day, as well as the deep respect for elders, as key elements of his own heritage that he sees reflected in his adoptive culture. Familiar with the semiarid Sahelian region of central Africa, he also finds comfort in El Paso’s often misunderstood climate. Where non–desert dwellers see dusty, dry, and barren, El Pasoans see Franklin Mountains State Park, which, at 27,000 acres, is the country’s largest wilderness park in an urban setting. They see the blast of yellow-orange that takes over the city each spring as the Mexican poppies bloom in large masses. They see thriving wildlife, including Mojave rattlesnakes, geckos, coyotes, jackrabbits, mountain lions, and more than one hundred species of birds. And, of course, they see flawless blue skies and three hundred sunny days per year.

I began to make sense of what El Paso meant to me after I learned more about the concept of the “third culture kid,” describing someone who spends their formative years outside the culture of either of their parents. Oftentimes third culture kids are the offspring of diplomats or missionaries, and have lived in many different places and therefore call no single place home. In my case, I am a third culture kid in the sense that besides a few trips to my parents’ places of birth, I never spent significant time absorbing either of my parents’ cultures, and I therefore adopted elements of the culture of my surroundings in El Paso. As a multicultural family, so far away from any extended family on both sides, we struggled to establish or maintain cultural traditions that reflected the heritages of my parents. I used to feel frustration that my parents hadn’t passed down any identifying customs to help ground me in my identity and connect with the extended family I seldom saw. But when I look back, we did have a tradition—that of the borderland, the place that embraced us with cariño.

In elementary school, that tradition looked like my classmates and me donning pink and yellow ruffled skirts to learn a folklorico dance to the classic “De Colores” for a school performance. Later it was the quinceañeras, where I watched my friends become women as their parents gifted them a pair of commemorative high heels. In high school, it happened through dancing cumbia just across the Rio Grande from our sister city of Juárez, at the Chamizal National Memorial, a park and cultural center established to commemorate the agreement between Mexico and the United States that settled a centuries-long dispute over the border’s location. At Christmas, it tastes like red tamales from Gussie’s on Piedras, the glow of thousands of luminarias on Scenic Drive, and journeys in Las Posadas in the nearby town of San Elizario. During Lent, it’s the aroma of caporitada, the delightfully sweet and salty cheese-filled bread pudding gifted by an old friend to my mom at church each year. In the summer, it’s the cast harmonizing to songs in “Viva! El Paso,” the annual musical performance that recounts the past four hundred years of El Paso’s history in an outdoor amphitheater tucked away in a canyon in the Franklin Mountains. In unexpectedly spiritual moments, it’s the mesmerizing vision of the matachines as they dance and rattle their instrumental gourds.

In spite of the cariño, I understood early on that my family was “other” in El Paso, and that an antiblack sentiment persisted in some corners. I remember the heat rising in my cheeks as my parents spoke French in the grocery store, oblivious to the gawking around them. I recall the never-ending search for a stylist who knew how to care for my dense curly hair, and the shame I felt when more than one turned me away, recoiling at my frizzy texture. I still feel, with stinging clarity, the moment when a classmate derisively called me “blackie” on the elementary school playground, and the unsettling realization that this wasn’t just his observation of my skin tone but a disparaging remark intended to make me feel less than.

And yet, for the most part, I felt and continue to feel a sense of solidarity with the community where I was raised. In fact, I feel privileged as a person of color and the child of an immigrant to have grown up in a majority-minority city full of immigrants and their descendants. Certainly, I do not forget that what I view as essential multiculturalism, others, especially in recent years, perceive and broadcast as a threat to their sense of nationalism. It is this demonization of the border, those who inhabit it, and those who are making their way to it that pushed a white man from Allen to take the lives of 23 people in a mass shooting in an East Side Walmart on August 3, 2019. A few days after Christmas last year, I visited the memorial for the victims that was erected in the Walmart parking lot, and wept in my car as I grieved for the lives and the sense of safety that this man had stolen from us. I continue to feel anger that no matter how much we preach “El Paso Strong,” we may never fully recover from the trauma of that hate crime.

Toni Morrison, my favorite author, once said: “In this country, American means white, everybody else has to hyphenate.” To the rest of the country, many El Pasoans have a hyphenated or asterisked identity: Mexican-American, Latino, Hispanic, first-generation American. Even though my hyphenation looked different from that of most of my friends in El Paso, I felt connected to them by our shared sense of multiculturalism and the universal grit passed on to us by our immigrant ancestry. Growing up in El Paso was a gift that shaped how I’ve viewed my place in every community in which I’ve settled in my adult life.

Now as my mind and body desperately seek refuge in this public health crisis in my home of New York City, I catch myself dreaming of El Paso’s warm embrace. I think of my mother who, at my age, found profound and unexpected beauty blooming in the severe desert conditions. I think of my father, who experienced peace in a new community after years of exile from his own. While I’ve certainly felt more in rhythm with my Blackness and African immigrant identity since leaving El Paso, I have yet to find a place where I feel at home the way I do there.

That’s the paradox I’ve come to understand about El Paso: in spite of its quasi-ethnic homogeneity, or perhaps because of its majority-minority identity, it’s a nourishing place for people who don’t quite fit any typical “American” mold. In our binational and bicultural identity, my family reflects the beautiful ambiguity of a border town. And though I’m not certain I’ll live in El Paso again, I know it will always be home.