A yellowed, faded, and crinkled telegram hangs behind glass on a wall at the National WWII Museum, in New Orleans. It is lasting evidence of a social and political revolution that raged in Texas in the years after World War II. Lyndon B. Johnson, then a U.S. senator, sent this message on January 11, 1949—75 years ago today—to Dr. Héctor P. García, a Mexican American civil rights activist in Corpus Christi. “I deeply regret to learn that the prejudice of some individuals extends even beyond this life,” Johnson wrote. He explained that he had arranged for the remains of Felix Zepeda Longoria, an Army private from the South Texas town of Three Rivers who had been killed in action three and a half years earlier, to be reinterred in Arlington National Cemetery. Johnson concluded, “I am happy to have a part in seeing that this Texas hero is laid to rest with the honor and dignity his service deserves.” He was writing in response to what would become a national outrage: the refusal of a local funeral home director to allow the Longoria family to hold Felix’s memorial service in its chapel because they were Latino. This telegram, part of the Special Collections and Archives of the Mary and Jeff Bell Library at Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi, is now on loan to the National WWII Museum, where visitors to the newly opened Liberation Pavilion can read it themselves.

Most Texans will not be familiar with the Longoria Affair, as it’s known, though the controversy was a defining moment in Texas history. It had lasting effects on the fight for Mexican American civil rights and on the careers of Garcia and Johnson. But this story as it’s typically told is about the many people and groups who fought over the symbol of Felix Longoria. Missing is the Felix Longoria who lived.

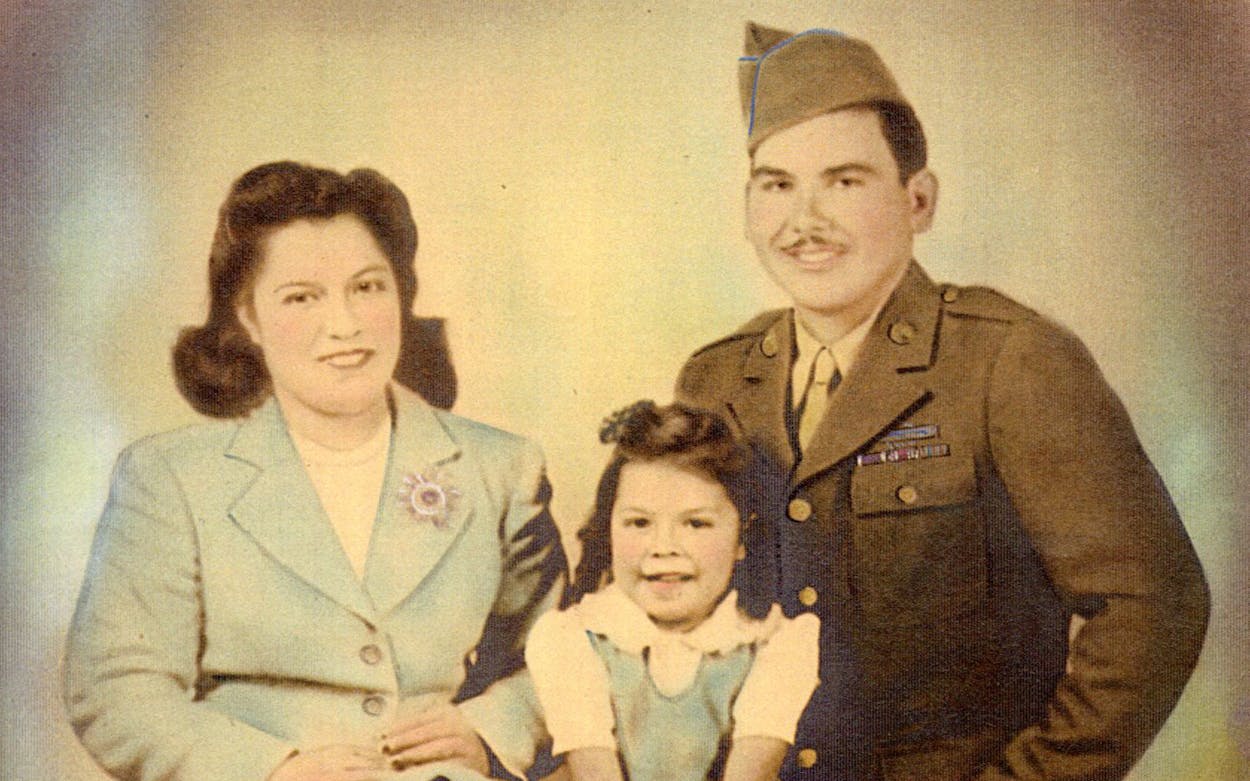

Historians differ over some minor details but agree on the larger picture: Longoria was an ideal representation of the all-American citizen-soldier of World War II. Nearly six feet tall, the brown-haired, brown-eyed, physically fit young man was shaped by hard work and duty. His father, Guadalupe Longoria, settled his family in Three Rivers, about 75 miles southeast of San Antonio, in 1913 at the town’s founding. Born in 1920, Felix was the youngest of four sons. While ultimately marginalized due to racial segregation in the town, his father nevertheless enjoyed a respected status as an intermediary between white and Latino communities. The elder Longoria’s sons often worked by his side in his fence-building and brush-clearing business. Felix began performing adult labor at the age of eight or nine, from which point he only went to school once or twice a week, resulting in his not getting past the third grade. In his late teens and early twenties, he also toiled in the South Texas oil fields as a welder and truck driver. Felix was well-liked and had an easy way with people. He met Beatrice Moreno in Three Rivers when he was sixteen, and they married two years later. Over the next several years, the young family shuttled between the small town of Three Rivers and the nearby city of Corpus Christi, looking for more and better work. Their daughter Adela, nicknamed Adelita, was born in 1941. Beatrice remembered Felix as a loving husband who liked dancing; Adela remembered him as a doting father. Decades after his passing, Beatrice could not recall her Felix without tears.

Felix Longoria entered into the armed services in November of 1944, convinced that he needed to serve. Despite having premonitions about his death, he pushed those fears aside. He joined the U.S. Army as a private, with his basic training occurring at what was then Fort Hood. (In 2023, the base was renamed Fort Cavazos after Richard Cavazos, the nation’s first four-star Hispanic general, a native of Kingsville). In the spring of 1945 Felix received his orders. He was being deployed to the Philippines. Years later, Adela hazily remembered traveling with her mother to a town near Fort Hood to say goodbye before he shipped out. On that day, father danced one last polka with wife and daughter.

Longoria’s Twenty-seventh Infantry Regiment supported the major offensive of General Douglas MacArthur to retake the Philippines. On June 16, 1945, while on a volunteer patrol to mop up lingering resistance outside Luzon, Longoria was killed by a Japanese sniper. The U.S. Army laid Longoria to rest in the Philippines alongside many other U.S. soldiers who were killed in action. Though his time in combat was short, it revealed that the gentle, friendly, young family man had iron within him. He earned a Bronze Service Star, a Purple Heart, a Good Conduct Medal, and a Combat Infantryman’s Badge.

The next several years were difficult for Beatrice, who struggled to move forward with her life. Then, in late 1948, she received a telegram from the Army asking her where to ship her husband’s remains, as they were in the process of being reinterred from the Philippines. This was an agonizing moment for Beatrice, who had to make difficult, long-term arrangements quickly while she relived the worst part of her young life. Though she’d since permanently moved to Corpus Christi, she decided that laying her husband to rest in his hometown of Three Rivers was the right thing. This was where his family resided, where the couple first met, and where they had been happy. But the only funeral home in the town denied her the use of its chapel for a memorial service. The mortician was quite clear that “the whites would not like it.”

In addition, Private Longoria’s grave would be relegated to the Latino section of the town’s segregated cemetery—on the far side of the same fence that the Longoria family had built for the city years before. Beatrice had experienced racial discrimination, of course, but this denial was still a surprise given the circumstances. She made her way back home to Corpus Christi, where her parents and siblings were waiting. Under tremendous stress and grief, she broke down sobbing. Her sister quickly arranged for the mediation of Corpus Christi community leader and physician Héctor P. García. Highly educated and a veteran, García contacted the mortician, Tom Kennedy, directly to plead for the family’s use of the chapel. Though Kennedy was also a veteran, he refused to change his mind, giving García a brusque reply.

Private mediation having failed, the situation was now public. García happened to have just started a fledgling Mexican American advocacy group, the American GI Forum, that was then focused on the unfair distribution of veterans’ benefits to Mexican Americans. García and the members of the GI Forum quickly adopted the Longoria matter as their cause. For them, Longoria was a powerful symbol of the discrimination experienced by Mexican American citizens in nearly every facet of daily life in Texas. That such racism extended to the grave, even for those making the ultimate sacrifice, erupted as a national media sensation. A headline in a Port Huron, Michigan, paper read simply “Disgraceful Incident.” In Coleman (near Abilene), the local paper ran a front-page photo of Felix’s parents, with grim expressions, holding a framed portrait of their son. The caption described them as “slightly bewildered by the turn of events.” García wrote to Texas’s newly elected U.S. senator, Lyndon Johnson, to ask for his help, and Johnson quickly intervened by arranging for a hero’s reinterment at Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C., for which the family was tremendously grateful. Beatrice told a New York Times reporter that she hoped the sorry episode would prevent similar discrimination in the future. “I’m all mixed up about this,” she said. “I am glad, of course, that Three Rivers has come to feel the way it has. Maybe it will help others.”

History would prove her right. The controversy had lingering effects for many of its advocates: Johnson garnered strong Mexican American support for the rest of his storied political career. García and his American GI Forum became national forces for Mexican American civil rights through important court cases on education and criminal justice, such as the successful 1954 Texas jury discrimination case of Hernandez v. Texas before the U.S. Supreme Court. The image of a decorated war hero being denied a memorial service in his hometown energized the Mexican American civil rights movement in Texas and across the nation into a more ambitious and active phase in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Not everyone agreed with this narrative, however. At the time, the state Legislature organized sham hearings that were designed to whitewash the racist event and, perhaps more important to lawmakers then, the bad publicity. Vindictively, Jim Crow supporters within the town of Three Rivers feverishly denied racism, seeking to discredit Longoria, his wife, his family, Johnson, and García with counternarratives of family disfunction and immorality. Hurtful and misleading narratives—that Beatrice Longoria dated another man while her husband served, that the denial of the memorial service was to prevent a family brawl—continue to this day. They live on despite the fact that the Longoria patriarch refused to sign statements to such effect pressed upon him by town fathers. This pressure was so great that the elderly gentleman had to temporarily leave town for his health.

This denial of history has extended into the twenty-first century. In 2009, a Texas state historical marker was placed in downtown Three Rivers, but—in part due to opposition during the planning process—its language is euphemistic and ambiguous, describing the funeral home director’s refusal as “widely interpreted to be racially based” and noting that “at the time, separation between Anglo and Mexican-American citizens was commonplace.” Repeated efforts to rename the town’s post office in honor of Longoria have also failed. In 2004, a campaign to name the post office for Longoria earned the support of numerous activist groups and Congressman Lloyd Doggett, but after pushback from the community, the proposal was scrapped. “Local people don’t want this,” Three Rivers resident Patty Reagan told a Los Angeles Times reporter. “We like the name the way it is.” In 2022, U.S. representative Vicente Gonzalez again introduced legislation to change the name; the bill didn’t make it out of committee. Gonzalez’s press secretary, Mauricio Armaza, told Texas Monthly that Gonzalez won’t reintroduce the bill, since his district no longer includes Three Rivers. The town is now represented by Monica De La Cruz. “We hope that Congresswoman De la Cruz will continue this effort,” Armaza wrote in an email.

Felix Longoria’s life touched upon the lives of all Mexican Americans who served or knew those who served. And this is a story that resonates today. Latino veterans still face disparities. They earn less than their white counterparts and are more likely to struggle to find a job after leaving the military. Denying Longoria’s family an opportunity to formally grieve at the only funeral home in his hometown was an indignity to his memory. It was an indignity to his entire family. It was an indignity to all Mexican Americans, more than 350,000 of whom served in World War II. Latinos nationwide saw their own sufferings—large and small—reflected in this ugly episode. This explosion of disgust fueled a new, more aggressive phase of Mexican American civil rights. But while the story’s outcome is important, an underappreciated aspect is the way Private Longoria’s virtuous life embodied the all-American values so many of his countrymen aspired to. It is not just the death of Felix Longoria, but his life that is key to understanding the Longoria Affair.

- More About:

- Texas History

- South Texas