When I was seventeen, just weeks into my senior year of high school, my parents told me that they’d be moving the family across the country. After struggling for several years to carve out a living in the face of diminishing opportunities in our fading Rust Belt community in northwest Indiana, my mom and dad—a nurse and a salesman, respectively—had sought out and found greener pastures in McAllen, 1,465 miles away from all my friends. They’d both be working for a small medical supply company started by my aunt, whom I hadn’t seen since I was little. My family had moved around enough when I was a kid for me to know what that looked like: trying to pretend that it would be a grand adventure, even as I said goodbye to my friends and prepared to start over—this time in Texas, of all places.

My journey to Texas ended up being delayed. My folks uprooted the family to McAllen right around Thanksgiving, but concern over whether I’d be able to graduate with the rest of the class of 1998 if I moved led me to stay behind. I bounced from living with a cousin to sleeping in the basements of a few friends’ houses in order to finish high school. The reprieve wouldn’t last forever. I wasn’t college-bound, so I didn’t really have a plan except to finish high school and then land in a place I knew only as the home of George W. Bush and giant pickup trucks. It might shock a student who grew up taking Texas history classes in middle school, but the Lone Star State didn’t occupy a big place in my imagination. My friends and I had watched Dazed and Confused a bunch of times. That was about all I knew.

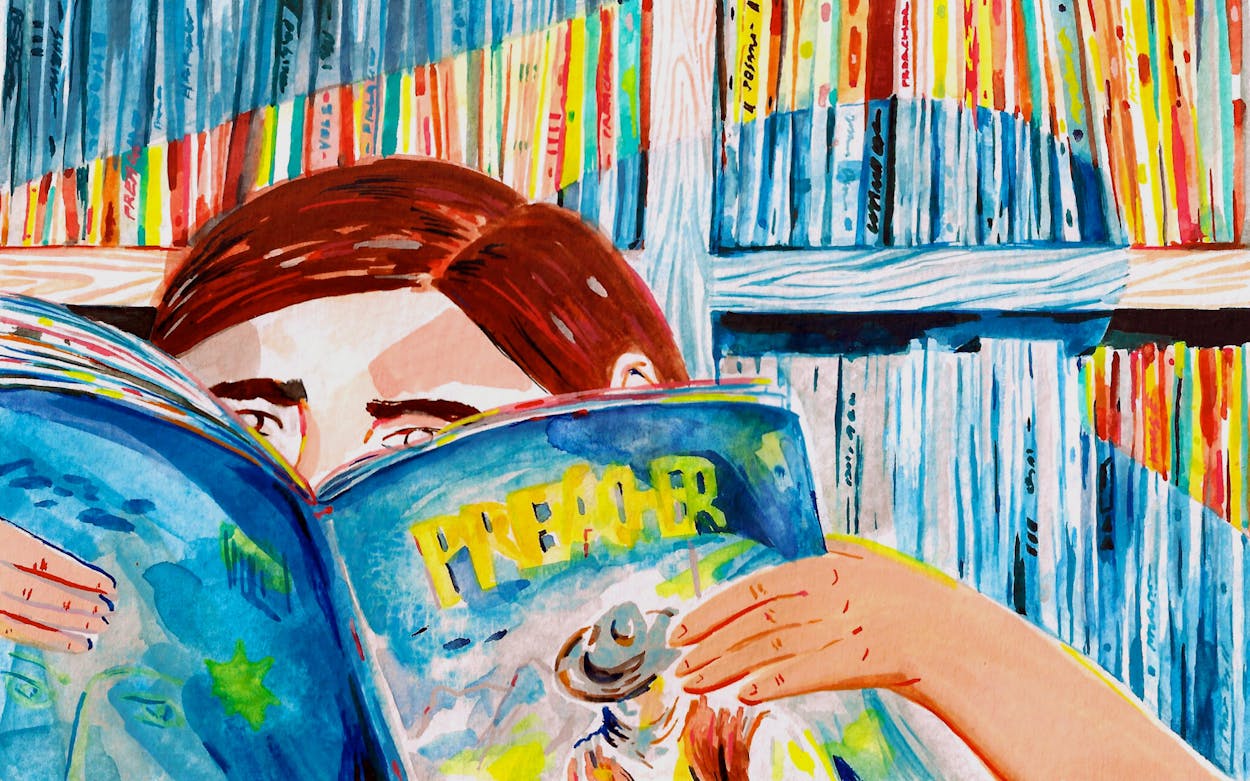

After my parents moved away, I adopted an unofficial second home: Clubhouse Comics, a spacious store with a wide selection of comics and graphic novels, and a loft area where I could hang out, watch Buffy, and play Magic: The Gathering with a gang of regulars. The store was a mile and a half from school, and on days when I didn’t have anything else going on, the manager was willing to let me come in after school and stay till he locked up. One afternoon, as I was complaining about my eventual move to Texas, he decided to help. He handed me a copy of the first volume of a graphic novel called Preacher, by the Irish writer Garth Ennis, with illustrations by British artist Steve Dillon. The cover art depicted a trio of badass-looking figures—a swaggering preacher, a tough-looking blond woman in a sports bra, and a sunglasses-wearing sidekick taking a drag off a Marlboro—walking away from some sort of smoking heap and directly toward the reader, the words “Gone to Texas” above them.

Preacher instantly became an obsession for me. I devoured that first volume, in which I learned who those heroes on the cover were: Jesse Custer, with his quest to find God; Tulip O’Hare, the mysterious hit woman whose heart he’d once broken; and Cassidy, a hard-drinking Irish vampire. I began to set aside a little bit of my paycheck from my after-school job at a pizza place to buy the subsequent editions. It was the story I’d been seeking, full of big ideas about God, masculinity, honor, and right and wrong. All of those themes were wrapped up in an aesthetic of Texas outlaw cool, full of heroes out of a postmodern western or a Willie Nelson concept album (the series opens with the first lines of his song “Time of the Preacher”), combined with gleeful, supernatural horror, immature jokes, and a whole lot of swearing. To my adolescent mind, it was the distillation of everything I was seeking.

Preacher is the story of Custer, who gets a superpower called the Word of God when an all-powerful spiritual entity winds up in his head, allowing him to speak commands that must be obeyed by all who understand them. Custer uses his power to seek out the Almighty himself, in order to ask him why the world is the way it is. He approaches his mission guided by the simplified moral certainty of someone who learned right and wrong from John Wayne movies. Over the course of around 75 issues, Jesse and his friends travel the globe—from West Texas to a grim, seventies-era Scorsese vision of New York, to France and on to New Orleans, to the Hopi desert, and then back to Texas—in pursuit of the Lord. I started to think, well, hell, Texas might be kind of exciting.

Revisiting Preacher as an adult, I can still recognize why the series meant so much to me. Ennis, an Irishman writing a story that paid homage to the American westerns, horror, and war movies he grew up watching, romanticized Texas as a sort of ur-America, with a convert’s zeal. His version of Texas heroism was drawn from a hodgepodge of sources and filtered through a postmodern lens, as interested in deconstructing the mythos of its setting as it was in glorifying it. It was the sort of nuance that I craved as I was building my own identity: I was old enough to know that the tropes of many of the stories Preacher invoked were jingoistic, sexist, and racist—but also that they were fun, exciting, and cool, and I was thrilled to find a comic book that was as interested as I was in trying to reconcile those things.

The series starts with a heavier focus on mythologizing than it does on deconstruction, but as it progresses, that begins to flip. Jesse’s relationship to masculinity is drawn straight from John Wayne, whom he idolizes. Early on in the series, he recalls the farewell his father gave him before he was murdered, telling the seven-year-old Jesse, “You gotta be like John Wayne,” and laying out rules for life: “Don’t take no s— off fools, and you judge a person by what’s in ’em, not how they look,” he says. “You gotta be one of the good guys, son, ’cause there’s way too many of the bad.” After his father is killed, Jesse sheds his final tears. “I knew John Wayne never cried,” he explains, “So neither did I.”

Over time, we learn that it’s all more complicated than that. Jesse’s rigid moral code, initially presented as a distillation of the Texas values instilled in him by his father and his heroes, leads him to come up short when navigating the complexities of the world he finds himself in. Freezing yourself at a child’s idea of what a man should be is no way to go through life, after all. The way Jesse’s ideas of morality, honor, and loyalty get flipped from a mission statement to a set of limiting factors as he deals with racism, his own deep-rooted sexism, his dearest friend’s predatory nature—all of that was downright revelatory to me as a teenager.

As the series approaches its climax, it connects the flaws in Jesse’s heroic stance with the ways that the Texas mythology, too, falls apart under closer examination. “Look too close and the legend cracks, but then, that’s legends for you,” the narration to the final story arc begins, as Dillon illustrates pages of the night falling on the Alamo. “Was Bowie a slaver, a drunk, a psychotic? Did Crockett beg for his life before Santa Anna, for mercy that could never come? Are heroes nothing more than desperate men?” it asks. “To dwell on such things is to miss the point.” The myth can matter, even if it doesn’t match reality—and part of growing up is recognizing that we’re able to take the meaningful parts of the stories that shape us, and benefit from the lessons they instill, without clinging to them as the basis of our grown-up identities.

That, ultimately, is the story of my relationship to Preacher too. If you ask me today if the series is good or not, I’m not sure I can answer the question. Revisiting it, there are moments that feel dated, jarring, or cringeworthy, and I know that there are things I took from the book that reflect the personal journey I wanted to be on more than, perhaps, the source material itself—values that I found in Preacher because I was eighteen years old and trying to grow up to be someone I could respect.

My late teens were, by necessity and circumstance, a transformative point in my life. I wasn’t living at home anymore, and I knew that I would be off to start a new life in Texas a few months later. The idea of landing in a new place, without either the friends I’d had from high school or the structure of going away to college, made me reconsider who I wanted to be. Preparing to go to Texas was scary, but it was also an opportunity to reinvent myself, and I knew that some of the things that I liked doing with my friends—watching South Park every Wednesday, idolizing Quentin Tarantino movies, driving around listening to Denis Leary routines—were more like habits than part of the person I really wanted to be. Preacher was like a bridge between the two. It had its own irreverent sense of humor, and it validated my conviction that, yeah, westerns were cool. But as I started to recognize what my actual values were, and notice the ways that the things I identified with were inconsistent with them, Preacher had something to say about that too. I was looking for something that said, “You can still be tough, you can still be funny, you can still be a man, you can still think a lot of your old heroes are cool, and you don’t have to turn into a bully to have those things.” I don’t know if anyone else who read Preacher would identify that as the point of the series, but it’s what I wanted to find at that point in my life, and I found it.

To me, Preacher is a story about growing past your juvenile, self-destructive notions of masculinity and learning to treat the women in your life as true equals. It’s about doing the right thing, but not so much in the John Wayne sense of standing with your side and against the other guys at all costs—rather, it’s about accepting that doing the right thing sometimes means letting go of your pride, and holding yourself and your friends accountable, even when that comes at a price. Those things don’t feel as righteous as belting somebody in the mouth who deserves it, but I’ve always read that as Jesse’s journey in Preacher and tried to make it my own journey, as I’ve gone from Clubhouse Comics to a few decades of calling myself a Texan.

By the time I finished reading Preacher, I was living in the Rio Grande Valley. Life on the border didn’t look a whole lot like the Texas that I imagined while I was reading. On some level, even as a teenager, I knew that wasn’t the Texas I’d be moving to. The series itself told me that such a place didn’t exist, had never existed—that it was a little boy’s dream of a land of clear-cut heroes and villains. Like Jesse Custer, I was trying to grow up and be a man. I’m sure I’d have gotten there eventually, with or without his story to help me find it, but it found me—and I found Texas—at just the right time in my life. I didn’t wake up most mornings feeling like I had opened the first chapter of a sprawling epic. I put in a few weeks at community college, got a job at the mall, went to punk shows, and made a few friends who hung out at IHOP. But eventually I found my own adventure, and there were moments—when I would drive past the ranches along U.S. 83, or walk along the train tracks under an impossibly large sky, or, after I followed an old girlfriend up to San Antonio, when I’d sit at the Alamo at midnight writing in my notebook—that felt close enough to being in the Texas of myth for me.