As sixteen-year-old of skinny arms and knobby knees, I stood at the front of a U. S. history class with a big red poster board and a bit of self-righteousness. Our teacher had assigned a research project, and as I roamed the Brownsville library’s bookshelves without direction, I had found a tiny treasure: a book about a Mexican man from my own hometown. It was thin and floppy, written by a graduate student in history at the University of Chicago. The subject was Juan Cortina, the man who had rounded up an army and shot several men as he declared war against the violent change of power South Texas experienced when it became part of the United States. In an 1859 proclamation, Cortina decried the arriving Anglos for forming, “with a multitude of lawyers, a secret conclave, with all its ramifications, for the sole purpose of despoiling the Mexicans of their lands and usurping them afterwards.” In traditional historical accounts Cortina went down as a border bandit, a “plunderer and murderer.” But in 1949, Charles W. Goldfinch offered a different image, one that had lived on in Mexican border ballads, that rendered Cortina a man outraged by the plight of his people. And so, on a cheap slice of cardboard, I drew a balance with all the ugly descriptions on one side and all the pretty ones on the other. The moral of the story was simply that history had more than one telling. To me, this most basic idea was the most profound revelation. I did not fully realize it at the time, but Juan Cortina’s story was, in a way, my story too. For my family had been in South Texas at the time of the Cortina uprising and for more than a hundred years before, and in time they also would fight for the land they had lost, though with law books and lawyers instead of guns.

Anyone who remembers seventh-grade Texas history class knows that in textbooks the story of our state begins just far back enough to show how brave men with Anglo surnames had conquered a cruel, empty brushland. They briefly recount that this land had been a Spanish province, then Mexican territory. But there is no mention, for instance, of the great Mexican ranches that already dotted the area when the Anglos arrived or of the ranchers’ winter trips to the area’s cities, where there were social clubs, colorful silk dresses, romantic violin serenades. An entire way of life, governed by a sophisticated system that rewarded and discriminated based on birth, class, and skin color, slipped into the whiteness of pages, erased and selectively forgotten.

It was into that social system that José Nicolás Ballí was born—on the privileged side, to be sure. In 1749, 72 years before Stephen F. Austin would set foot in Texas, the first Ballís had arrived from northern Mexico to the province of Nuevo Santander, what is now the Lower Rio Grande Valley. There they would become a powerful landed dynasty. Ten years later, King Carlos III granted the offshore island, then called Isla de Santiago, to Nicolás Ballí, the grandfather of José Nicolás. But it was the grandson, by then a Roman Catholic priest, who surveyed the property, claimed it as his own in 1800, and put up a ranch there. With the help of a nephew, Juan José Ballí, he raised cattle, horses, and mules and worked to Christianize the area’s Karankawa Indians. Eight months after the priest died, in 1829, the newly independent Mexican government finally confirmed title to him and his nephew. By that time Isla de Santiago was already acquiring the name by which it is known today: Padre Island.

To Texans and Mexicans alike, Padre Island is a nice getaway for the limited budget, a beach resort close enough for three-day weekends. Here, Winter Texans dine on fresh fish while their relatives up north shiver through December. Here, college students drink a week of their lives away and dance with barely dressed strangers in sticky outdoor clubs. Rich Mexicans pick up tans during Holy Week and cruise late at night in their shiny Jettas. Skinny beauty pageant contestants strut around in high heels and wide smiles in hopes of a crown. But to the Ballís, the island whispers of a proud but sad past. The last family members to claim a piece of it sold out at the close of the Great Depression, expecting to receive royalties from its underground riches. They never saw a cent. The island’s very presence was a continuing reminder of their fall from preeminence—until last summer, when a Brownsville jury heard their arguments and vindicated their claims.

News of the verdict appeared in dozens of papers nationwide, spread across the pages of the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, and USA Today, and as far away as Argentina. “Six decades after a New York lawyer bought Padre Island from a Mexican American border family, a jury determined Wednesday that he had swindled the family’s impoverished descendants out of $1.1 million in oil and gas royalties,” the Associated Press reported. Historians called it “revolutionary,” an overdue acknowledgment of a shady time in Texas history during which hardworking people were stripped of their land. My branch of the family was not involved in the Padre Island lawsuit, but distant relatives were, and we celebrated together. “The victory of the Ballí heirs,” wrote Gilberto Hinojosa, a dean at the University of the Incarnate Word and a South Texas historian, “confirms a heartfelt sentiment among Mexican Americans that this is their land and they belong here.” Once a family whose last name few outside the Valley could pronounce (By-yee), the Ballís became, almost overnight, world-famous.

Yet the victory took centuries of work and lifetimes of hope. It took generations of white-haired matriarchs and patriarchs passing on the story to their grandchildren, decades of searching for old documents that would speak the truth. It took marches and massive family meetings and some miracles too. The Ballí family is a family of self-made genealogists, historians, lawyers. When nobody would acknowledge their roots, the Ballís unearthed them. When nobody would tell their side of the story, they wrote and proclaimed it themselves. When nobody would represent them, they asked to approach the bench, Your Honor, and they said what they had to say. You see, the Ballís weren’t just born Ballí, they became it. And once they began to change, there was no turning back.

“I’ve been telling people I’m gonna move on with my life after this,” Pearl Ballí Mancillas mumbled as we waited in the Brownsville federal courthouse for the jury’s verdict. She sighed. “But then I ask, ‘What is my life? This is all I’ve ever known.’ ”

The history of the Ballí lawsuit really begins in the blurry years after Padre Ballí’s death. Just months afterward, his nephew, Juan José, sold the island, but the story goes, Santiago Morales, the Mexican man who bought it, may have suffered buyer’s remorse. Exactly what was happening on Padre Island at that time is impossible to know. The Ballís had divided the island among themselves into two large tracts, north and south. At the same time, Anglos who arrived from throughout the United States and Europe set foot on other parts of the island and called it theirs. Among these was John Singer, the brother of the man who invented the modern sewing machine. And there was Pat Dunn, the famed Duke of Padre Island, who, the Ballís’ lawyers say, erected guard posts to keep others out, and in 1928, claimed title to almost the whole island through squatter’s rights. The whole time, various Ballís with island roots and from other landed branches had been trying to determine what they owned. One of them was Ignacio Ballí Tijerina, whose ancestors had possessed an even larger tract on the mainland known as La Barreta, where cattle baron Miflin Kenedy later built his ranching empire. “Before the law, we are all equal men,” Tijerina wrote in the articulate, typed notes he left behind. “Before society, we are not.” Over lunch at one of the five tables in the Brownsville Cafe, in a white T-shirt with an imprint of the Ballí coat of arms, his daughter Herminia Ballí Chavana tells me the story. Her father and his brothers, she says, were approached in 1910 by a Mexican American man who had been sent by an Anglo lawyer to offer them 25 pesos each for their signatures. His brothers refused the offer and instead sent Tijerina to the Mexican archives in Reynosa to find out what their ancestors had owned.

But he was not let in, he wrote in his notes, so he sought special permission from a Matamoros judge some sixty miles away, then made his way back to Reynosa. The archives were in disarray. “Los americanos,” as he called the Anglos, had already been there—without the extra trip to Matamoros. They pieced together land ownership through wills and birth and marriage certificates, bribing the archives’ keeper for some of the originals or simply taking what wasn’t theirs. Herminia’s voice grows furious as she paraphrases her father’s memoir. “The Anglos would steal the deeds,” Herminia says angrily, her hand shaking violently as she grabs a white paper napkin from the table and stuffs it under an imaginary jacket. Later they would hire locals to pay landowners to sign documents that some of them could not even read, sealing the transfer of their land.

As the research of land ownership progressed, speculation abounded and theories surfaced. Some of them seeped into the newspapers, and one of these articles, a 1937 story that appeared in the Brownsville paper, was mailed to a prominent New York lawyer named Frederic Gilbert by a business associate in South Texas. The article reported that a document had been found showing Juan José Ballí’s sale of the island in 1830 to Santiago Morales had been rescinded. This suggested that a group of Ballís might still hold title to more than half of the island. In New York, Frederic Gilbert summoned his 24-year-old nephew, Gilbert Kerlin, a sharp young graduate of Harvard Law School, and gave him his first assignment: Go down to Padre Island and buy the Ballís’ titles.

And so Gilbert Kerlin, who today is 91 years old, stepped into what had become common South Texas practice: Figure out who owns land, round them up, and offer to buy. He was a “baby lawyer” then, as attorneys in the island case described him in court last summer, and he spoke no Spanish. But he was resourceful, so he got help—the best help, in fact, he could find. To track down the Ballís who might still have claims to the island, he hired one of their own, a man named Primitivo Ballí, who was paid $750. Primitivo’s daughter Librada, who testified at the trial, would be Kerlin’s secretary. And for legal advice, Kerlin knocked on the door of Francis William Seabury, a powerful lawyer well known for his extensive research of South Texas land grants. Originally from Virginia, Seabury had become a prominent Valley politician and served four terms in the Texas Legislature, including one as Speaker. Some spoke English; some did not. Most weren’t very educated. But the Ballís who descended from the priest’s nephew held claims to the beach that Kerlin’s uncle thought might be worth something. At the time, the island was but an empty swath of sand, with only a Coast Guard station and an abandoned fishing shack. Yet underneath lay the slick stuff of Texas riches. Seabury tried to warn Kerlin off. “Developments since you left confirm my original opinion that you would have no reasonable chance of making good title to any part of Padre Island acquired by deed from the supposed heirs of Juan José Ballí,” Seabury wrote Kerlin’s uncle in a letter dated August 11, 1938. Had the 1830 rescission really occurred? It wasn’t entirely clear, Seabury argued. Almost prophetically, he closed with a warning: “Please do not go too fast in this matter. There is a fine chance for you and your associates to get badly stung if you rely on any fact that is not proven by almost conclusive evidence.” Undeterred, Gilbert instructed his nephew to press forward.

Eventually, 54 Ballís signed eleven deeds. There is disagreement over how much each was paid—suggestions range from nothing to $300—but one thing was clear: It was agreed, by deed, that they would retain a small portion of mineral rights, which was more than the cash-poor family was getting from the empty land anyway. Deeds acquired, Kerlin moved on, cutting deals with other island claimants and battling in the courts to secure as much of the beach as possible. In 1940 he faced off with the State of Texas, which had sued the Ballís and other island claimants in an attempt to take the acreage by which the property exceeded the 1829 survey dimensions, amounting to roughly two thirds of the island. The state eventually lost its case and was refused a hearing by the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1941 Kerlin sued the powerful King Ranch, which claimed to own a six-thousand-acre strip of the island. Lawyers for the ranch settled that case out of court, granting Kerlin half of the mineral rights to the disputed land.

Kerlin’s next challenge was daunting—to bring down Pat Dunn. Forming an unusual coalition through his lawyer Seabury, he banded with other Anglos who were claiming ownership of parts of the island. In 1942, while Kerlin was serving in World War II, they sealed that ownership when Havre v. Dunn was settled, then sat down to exchange 135,000 acres of land among themselves. Kerlin walked away with 20,000 acres, plus an additional 1,000 acres of mineral rights. That victory was temporarily jeopardized when, during World War II, the federal government announced that it intended to take the southern quarter of the island to use as a bombing range. The war ended before the government’s plan could be put into effect, allowing Kerlin to retain the land. He would strike one last time—in 1978, when he sued the state, which claimed to own 30,000 acres of mudflats in the Laguna Madre that he argued were part of the island. Like his other deals, the resolution of that case exemplified Kerlin’s knack for winning. When it was settled, in 1980, the state had lost 27,000 acres to the shrewd New Yorker.

The Ballís never heard from Kerlin again, never learned that such monumental lawsuits had been settled. And they never received the small royalty checks that would have justified the sale of their lands. In the early fifties Primitivo Ballí mailed several letters to New York; Kerlin responded to one of them by saying the family’s deeds had been worthless. So in 1953, the Ballí who would forever be shunned by his relatives for enabling their loss sent Kerlin a final, respectful request: Could the Ballís have their birth certificates back?

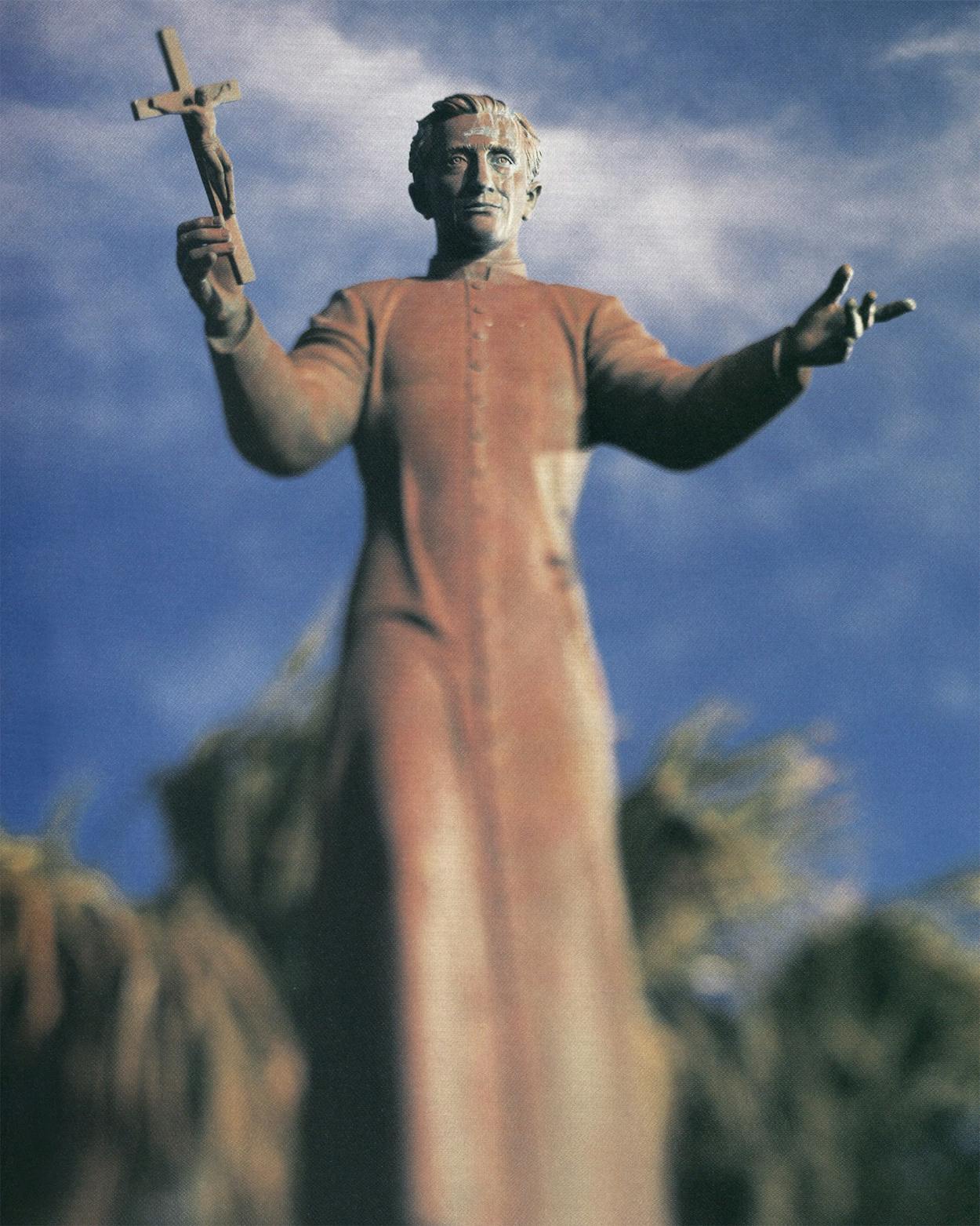

The streets of Brownsville are awfully quiet without Johnny. These aren’t his times anyway. In 2001 we don’t walk into government buildings and make demands; we don’t block streets until people listen to what we have to say, as Johnny liked to do. I wonder, in fact, what it would have been like for Johnny to sit still in the courtroom, as his sisters did, and listen to hours of testimony knowing that anyone who made a racket would be thrown out. No, that wasn’t his style. Johnny liked to be heard. I met Johnny Ballí when I was eighteen, and I haven’t seen him again. I was writing for the Brownsville Herald that summer, and he had caught my name in the paper; so one day he walked into the newsroom and, in that imposing way of his, asked everyone at once, “Who is Cecilia Ballí?” They pointed him to my desk, and he walked up in his boots and shook my hand hard. Who was my father, he wanted to know, and did I know the Ballís once owned Padre Island? Ask the residents of Brownsville and they will say they remember Johnny too, the liquor-tax collector at the Gateway International Bridge whose life mission was to let the town know where the Ballís came from. You see, in my times, after Johnny had persuaded the Cameron County Commissioners Court and the Texas Historical Commission to put a statue of the priest on the island, being Ballí was an honor, a title that made people look at us with a little more respect, even if we had nothing to show for it. But in Johnny’s time, if he said the Ballís had owned the island, people, including family friends, laughed.

Decades had passed since Primitivo Ballí had heard from Gilbert Kerlin, but the Ballís’ memory of the New York lawyer, instead of withering, grew thick layers as time passed, like the bark of a tree rooted stubbornly in their back yards. Those who had signed over their deeds remained mum for a generation, shamed about what had happened to them. But as the elders began to grow old, they started telling the story to grandchildren. For a family that had descended from landed gentry to working class, the tale became its members’ only heirloom. It lost details as it transcended generations but picked up meaning as other branches of the Ballís claimed it as their own, a moral to be learned about trust and the lot of little people.

Johnny was born into this culture, the grandson of one of the 54 Ballís who had signed over their deeds to Kerlin. In the late sixties he began agitating. A charismatic man recognized instantly for his cowboy hat and his commanding presence, he became the family spokesman, setting out to shake the city’s conscience. Once, he stomped into a county commissioners’ meeting and declared, “As a member of the Ballí family, I am officially claiming possession of Padre Island.” “He was quickly arrested,” wrote his sister Pearl in a 126-page book, where she pressed her family’s plight between two hard, brown covers. The politicians weren’t interested at first, but Johnny was able to persuade local businesses like Cowen’s Used Cars and the Flamingo Motel to dot the town with “Erect Statue of Padre Ballí on Padre Island!” portable signs. He led family members and supporters on three marches to the beach, in one case blocking the causeway to the island with their cars as they waved the U.S. flag next to the Ballí coat of arms. Finally, in 1983, the bronze arrived at its site at the entrance to the beach and was hoisted out of its wooden crate, with Johnny watching emotionally. Like the good Catholic he was, he repaid the Virgin Mary for the blessing by making a sixty-mile pilgrimage by foot to the Virgin of San Juan del Valle shrine, television cameras trailing. The story is that when he arrived, in the middle of mass, the congregation clapped and wept.

Today Johnny sits at home with brain tumors, only sporadically comprehending what goes on around him. But although Johnny’s times have passed, the Ballí family as it is today is his legacy. For when others began to believe their story, the Ballís learned that there was power in numbers, in doing things systematically. They began to hold large family reunions. They sold self-published books. They went to the media. They formed organizations and held thoughtfully planned meetings. Those with computers constructed Ballí Web sites, family chat rooms where distant cousins could reconstruct their ancestries, announce family gatherings, and discuss strategy. Ballís began to check in from the various states where many of their parents or grandparents had relocated to do farmwork and realized they were part of a huge family. Estella Ballí Trimble didn’t know she had any cousins until her mother, nearing death, told her. So Estella set off to find them. “Can you imagine living in this world and not knowing you have three thousand relatives?” she asked me once over the phone. “It’s like counting the stars.”

But the Ballís knew it wasn’t enough to say they had lost their land. In the end, legal justice would require evidence, and only a few lines of the family might have the documents needed to prove that they had been wronged. While Johnny was organizing in Brownsville, another island heir, a onetime paralegal named Connie Gonzales who lived in Houston, had begun to do research. It pained her to think that her grandmother had migrated back and forth to Wisconsin to work in a cannery while Padre’s new owners had gotten rich. So for years she spent days in the archives of county records throughout South Texas, her husband and children touring the cities they visited while she searched in stuffy rooms for any documents that mentioned the Ballís.

For decades, when family members had talked of what had happened, they had referred to Kerlin only as “the gringo” or “the bolillo,” and there were so many Anglo names in the title abstracts that Gonzales scoured. She didn’t even know if the man her grandmother had dealt with was still alive. All she could do was jot down every name, then run them by the elders in her family. Gilbert Kerlin, one aunt thought, sounded familiar. Gonzales’ hopes soared. She called New York information: The name of the law firm he had worked for still existed. An operator provided the number. She placed two calls, left messages, and waited in suspense.

Two weeks later her phone rang, and a voice at the other end said it was Gilbert Kerlin. “At that point,” she recalls vividly, “I asked him point-blank if it had been him. And immediately he said, ‘Yeah, but those deeds weren’t valid.’ ” And then he said something else: Did she have a lawyer? Because the burden of proof in a lawsuit would be on the Ballís, and fighting him was going to cost a fortune.

Gonzales pressed forward. With her brother, she had created el Comité Padre José Nicolás Ballí, and they summoned other Ballís through classified ads in the Brownsville Herald. At the first meeting, she joined forces with Johnny and Pearl. She continued her archival research, and in 1985—almost magically, it seemed—she found her treasure. In the bowels of the Kleberg County Courthouse, in Kingsville, she found the original eleven deeds the Ballís had signed over to Gilbert Kerlin in 1938. “It was like gold,” she remembers. With only enough cash to copy a handful of them, she had to send a niece back for the rest.

Kerlin had a point, though: As much as they had come to despise attorneys, the Ballís would need one. In 1991 the family hired Brian Scott and Murray Fogler of Houston. But after nearly two years of work, they washed their hands of the case. “I think the excuse was that there wasn’t enough production in the oil wells [on the island] for them to pursue it,” Gonzales recalls. My branch of the family, which had begun to pursue the La Barreta case on the mainland, faced the same problem. Individual families mustered little payments worth more than a week of groceries—$100 here, $200 there—to pay the expenses of their lawyers, who drove to preliminary hearings throughout South Texas and wined and dined as professionals do. The lawyers quit anyway. For most of them, the case represented a big gamble; the probability of winning wasn’t worth their time and expense, not to mention the difficulty of representing hundreds of people who were spread throughout the country and often couldn’t agree with each other. My uncle, a La Barreta heir, received a letter last year from a Dallas law firm that said only, “We regret to inform you that circumstances have developed which hinder our continued effective litigation of the lawsuit.” Two hundred twenty-three Ballís were dumped.

But in 1994 a young Houston lawyer named Hector Cárdenas, whose grandmother had signed one of the eleven Kerlin deeds, undertook the mission to save the island case. After his own law firm declined to take it, Cárdenas, who was just out of law school, contacted some twenty firms, to no avail. Even Houston’s top plaintiffs lawyers turned him down. Then, a lawyer who went to church with his aunt offered the name of Tom McCall, an Abilene native who is now a well-regarded Austin oil and gas lawyer. Meanwhile, Kerlin wasn’t the Ballís’ only adversary: The clock was ticking. While McCall was reviewing the case, a state district judge dismissed the lawsuit for want of prosecution. The Ballís had just thirty days to reinstate it. McCall agreed to take the case, then filed a motion to reinstate on behalf of Hector Cárdenas’ mother and four of her siblings—just one day before the deadline expired.

The story of what occurred next has become family legend. In April 1995 McCall showed up in a crowded state district court in Brownsville, where he argued that the case was not dead: He only needed a little time to sign up the rest of the family. Then, to prove his point, he turned to face hundreds of Ballís who were attending the hearing and asked, “Who here is going to join us?” Almost every hand in the audience shot up. By the time the room was cleared that afternoon, McCall had picked up at least a hundred new clients. The Ballí family, after all, would have its day in court.

Tom McCall never meant to reverse a family’s fortunes, never meant to refuel a South Texas movement to reclaim lands, never meant to help rewrite Texas history from a Mexican American perspective. At first, he just meant to win a lawsuit. He is a 52-year-old lawyer with an office nestled in the hills of West Austin. A quiet man who usually carries a smile, he has a straightforward character that makes him automatically likable. It is reflected in the way he maintains his cool in front of a judge, the way he often paces alone outside the courtroom during long waits instead of visiting with other lawyers at their table. Britton Monts, a Dallas lawyer who is McCall’s close friend and has teamed up with him in the courtroom for sixteen years, calls him “a real Don Quixote,” a man who believes in the concept of good over evil. Hector Cárdenas regards him as the true lawyer ideal. “Tom, I’ve got to say, is the closest to the Atticus Finch character in To Kill a Mockingbird that I’ve ever worked with,” he says. “That character is why I went to law school.” When he reviewed the Ballí case, McCall remembers, he instantly spotted an argument. Given that the history of the island was so muddy, he would have a tough time proving the Ballís had held title in 1938, when the Kerlin deeds were signed. So McCall turned to another legal strategy called estoppel, a way of saying a man will be held to the benefit of his bargain. It would prevent Kerlin from denying the validity of the Ballí deeds if he had previously used them to make other legal claims to the island. Seldom invoked today, estoppel was used long ago, before a sophisticated title system was developed to facilitate the tracking of property ownership. “We spent, maximum, ten minutes talking about it in law school,” Cárdenas says. In McCall’s view this was the perfect opportunity to apply it. So he joined up with Monts, then completed the legal team with his twin brother David, whose specialty is land titles, their associate Robert Johnson, and Cárdenas. In Brownsville, Cárdenas had asked Frank Costilla to step in as local counsel.

For five years they built a case. As time passed, the lawyers began to feel they had stepped into something truly bigger than life—something guided, it seemed, by an invisible hand. “It almost felt like fate was moving us along, and I don’t mean to sound superstitious,” Monts says in retrospect. “There are some cases that feel like they’re snakebitten from the start, but this one just felt like it was fated.” It seemed like fate, for instance, that Kerlin still had boxes of old letters his uncle had exchanged with Seabury regarding his island transactions, which he turned over to his Houston attorney, M. Steve Smith, when they were subpoenaed by the court. It was in reading those 30,000 pages of letters and documents, over months of trips to Smith’s office, that McCall began to suspect that the Ballís had been deliberately cheated from the beginning. He caught statements buried in that correspondence hinting that Kerlin, his uncle, and Seabury had conspired to leave the Ballís and their royalty interests out of Havre v. Dunn and the later cases that settled the title to Padre Island. In one letter, Seabury, who had told the court he represented both Kerlin and the Ballís in those cases, identified the former as his “real client.” Another letter revealed that Kerlin’s uncle had intended to “let the Ballí title, if such it may be called, die in Kerlin.” The more McCall studied the documents, the more he was convinced that the carving up of Padre Island after Havre v. Dunn was settled was designed to wash the Ballís’ claims out of the record. Although the island dealings stand out in Seabury’s legal career, those files did not go into the collection of his papers that was donated to the Center for American History library at the University of Texas at Austin but were separated and eventually passed on to Kerlin in New York, who kept them in a filing cabinet. “I’m sure,” says Robert Johnson, “Seabury never dreamed that the courts were going to give the Ballís the key to open that locked drawer.”

On those allegations, the island trial began in Brownsville on an unbearably hot afternoon last May. At ninety years of age, Kerlin returned to South Texas by plane, dressed impeccably like the prominent lawyer he had become, flanked by Smith and Brownsville attorney Horacio Barrera (ironically, the descendant of another Ballí branch). Ballís drove in by the carloads, ice chests and family albums in tow, from as far away as Florida and Illinois and California. Retired senior state district judge Pat McDowell arrived from Dallas to try the case, replacing a local judge who had recused himself. The trial had been moved to the federal courthouse, where the courtroom was completely filled with Ballís, with hundreds more waiting in the halls, all of whom could confront at last the man who had been, for years, a faceless villain.

He was instantly spottable at the defense table, frail but erect, his thinning silvery hair neatly combed and turned up at the ends. “Ahí está el viejo” (“There is the old man”), one gray-haired woman said as she took her tan leather seat. For a few seconds she stared indignantly. Through large, thick glasses, he peered back. He almost evoked pity sitting there that way, his cheeks sagging heavily over the corners of his mouth. The Ballís who had arrived in cotton and rayon and polyester might have been a little less condemning if they had known Gilbert Kerlin better, if they had been aware, for instance, that he is a charitable man who contributes heavily to environmental and preservation causes in New York and even donated land for Andy Bowie Park on Padre Island. But there was no way they could know him—not now anyway, sitting under the high ceilings of a chilly, elegant white courtroom. They had not spoken for decades.

One by one, they took the stand—Ballí grantors and their descendants, oil and gas consultants, a title lawyer. Kerlin, ever sharp, testified for eight contentious days. Because of the complexity of the case, jurors were allowed to take notes and slip questions to the judge. In the audience, family members filled their own notebooks with scribblings. While McCall and the rest of the Ballí team used hundreds of letters and documents projected on a huge screen to prove the conspiracy, Kerlin’s attorneys stuck by the argument that he had made to Primitivo Ballí long ago and to Connie Gonzales on the telephone: The Ballís’ deeds had been no good when they sold them in 1938. Kerlin did not, they argued, enter the Havre v. Dunn case relying on the Ballís’ deeds, as the family’s lawyers contended, but by using titles he acquired later through lawsuits and deeds from several Anglo families. If the Ballís’ deeds had been any good, Barrera told the jurors, “They wouldn’t be using this fancy term called ‘estoppel.’ ” In fact, if anyone had been cheated, it was Kerlin’s late uncle, they said, when he spent $80,000 to acquire and defend these worthless deeds. Kerlin was acting only as an agent for his uncle, and although the Ballís kept harping on how they had slipped into poverty, Barrera added, “Who’s poor and who’s rich doesn’t matter in the courts, because that’s the way of life.”

On the testimony went, for nine weeks. The jurors, attentive for the most part, began to grow nervous about being away from their jobs and slipped another question to the judge: “Once this trial is over, should a juror experience employment difficulties [directly attributable] to his/her jury service in this trial, what would be the avenue of relief?” The family continued to fill the courtroom early every morning, drawing family trees, proudly passing around snapshots of themselves standing in front of the courthouse with their attorneys. Kerlin appeared consistently too, shuffling in with small but steady steps, riding up and down the elevator alone, and reading the New York Times quietly. He would not discuss the case because of a gag order, but we had a pleasant chat one day about nothing important. Later that afternoon he gave me his business card with a small smile, ignoring his lawyer’s suggestion that we speak through attorneys, and for a moment, I wanted to like him.

Then the trial was over and the judge gave the jury 27 questions to answer. (In civil trials in Texas, juries answer questions and judges apply the law based on their answers.) Nowhere was the jury asked to decide whether the Ballís had actually held title to the island when they sold their deeds in 1938. Instead, the charge opened by asking whether Kerlin was “estopped” to deny the validity of the deeds. By making estoppel the basis of his case, McCall was able to get around the need to prove that the Ballís had a valid title to the island in 1938, which would have been next to impossible to do, given the long passage of time. Instead, he needed to prove only that the Ballís had been cheated. Based on a request from Kerlin’s attorneys, the judge tagged on an issue at the end: Were the Ballís guilty of waiting too long to bring this case to court?

When the judge called the jury in for a verdict four days later, on August 2, McCall blinked once, swallowed hard, then rose slowly. In the audience the Ballís filled every inch on the benches; teenagers, fathers, and grandmothers sat on the floor or stood in the back. About a dozen reporters were asked to stand along a side wall to make more room for the family. Before a row of chairs, a string of plaintiffs stood, clutching each other, eyes closed, heads imploring God in silent prayer. Kerlin was missing; he had been forced to leave for New York the day before, his lawyers said, because his wife, who was sick, needed him.

Wasting no time, the judge began to read what the jury had handed him. For the family, the answers that followed rang like sweet church bells. Was Kerlin estopped from denying that the Ballís’ deeds were valid? Yes. Did he acquire an interest in those deeds? Yes. Did he fail to comply with his fiduciary duty to the Juan José Ballí grantors and their heirs? Yes. Did Seabury breach his fiduciary duty to the family when Havre v. Dunn was settled? Yes. During that settlement, did Kerlin conspire with Seabury to breach Seabury’s fiduciary duty to the Ballís? Yes. During that settlement, did Kerlin conspire with Seabury to commit fraud against the Ballís? Yes. During that settlement, did Seabury commit fraud against the Ballís? Yes. Did that breach of fiduciary duty result from malice? Yes. Any way one put it, the Ballís, eleven of twelve jurors concluded, had been wronged—and in a blatant, conspiratorial way. “The documents were there, and that’s what I found so amazing,” jury foreman Cesar Cisneros, a retired school administrator, said later. “I just felt the evidence was so overwhelming that, as they say, hasta la pregunta es necia“—it was a moot question.

Less than an hour after the decision was read, McCall and his team arrived at the family’s celebration at the Fort Brown hotel, the same place where U.S. troops under General Zachary Taylor had gathered in 1846 to take South Texas from Mexico. More than one hundred Mexican Americans offered the lawyers a standing ovation when they entered, and someone cried out with deep pride, “Arriba Tom McCall!” Cameras flashed. Old women hugged him. But the victory would be tempered by what happened just a few days later. A week after the vindicating verdict, after hearing a string of family members describe their lives in poverty, the all-Hispanic jury refused to award punitive damages. One juror—the only one who did not sign the original decision—told a reporter that the Ballís did not deserve compensation for their economic fate, which was shared by countless other Brownsville families. “If you were poor,” the juror said, “you just had to struggle a little harder to get out of that hole, that’s all.” Another juror said that withholding punitive damages was the only decision all jurors could agree to. The outcome meant that a man whose attorneys said is worth $68 million would have to give back only what he had failed to pay.

Assuming that the decision is not overturned on appeal, the Ballís will get $3.3 million in damages for fraud and unpaid royalties, of which their attorneys will receive 40 percent. The jury also concluded that the Ballís should have received mineral rights to 7,500 (plus accretion) of the 20,000 acres Kerlin acquired in settling Havre v. Dunn. So they now will be due small but regular oil and gas royalty payments for that property. All of this will be divided among roughly three hundred plaintiffs. Kerlin does not have to file an appeal until a final judgment is entered, but he has already hired Rusty McMains of Corpus Christi, a prominent appellate lawyer.

It is ironic that the Ballís ultimately prevailed the American way—by hiring a damn good lawyer—and that their attorneys used a legal doctrine that originated in English common law, the basis of our country’s justice system. For it was the same system, sixty years ago, that created the loopholes through which their land had disappeared, and it was another Anglo lawyer who had authored their loss. Inevitably, some will see the case as something else, as the start of the repossessing of South Texas by Mexican Americans, who always have made up the majority of the population. But legal experts agree that most cases are lost causes because of statutes of limitations, lack of documentation, and transfers of land that were legitimate. Still, the Ballí case touched hundreds of people who have heard similar rumblings in their own families, and they have descended upon county courthouses and libraries, unraveling their own histories.

I must have been six when my father left Brownsville to attend a Ballí gathering in San Antonio and returned with tiny T-shirts of the Alamo for his three daughters. Like the rest of his siblings, our dad knew little about history and even less about law. I still have that shirt in a drawer back home, small holes where my bony shoulders used to rub. He died sick on a hospital bed, and other than a little bit of pride and lots of love, he couldn’t leave us much. He was a cab driver with cancer. He was 41. But he left us a special last name, and there lay the treasure. I guess, with time, I too became Ballí. I became Ballí when, on childhood trips to the island, we pulled up by the priest’s statue and admired how our last name looked engraved on a plaque. I became Ballí when, in high school, my twin sister and I penned a family history to show our classmates that ancestry ran much deeper than grandparents. And I became Ballí when, as a college freshman, my first A was on a paper about nineteenth-century relations between Anglos and Mexicans in Brownsville. “Can you believe how blessed we are to have been born into this family?” my sister asked in disbelief when news of the island trial went national. Because we descend from the priest’s uncle, ours is the branch that will now pursue the La Barreta case against the John G. and Marie Stella Kenedy Memorial Foundation. I haven’t decided whether to join the lawsuit, which is scheduled to go to trial on October 22.

The island victory, though, was for all of us to relish. In a way, its story is universal. For it is a story about how some people are washed out of their own histories. It testifies that important men like Seabury and Kerlin, like all other people, are both good and bad. And it offers a glimmer of hope that sometimes—not often, but sometimes—the little man does win. Sitting in a warm McDonald’s in south Houston, Connie Gonzales reminded me how Kerlin had prevailed in so many lawsuits over island ownership—defeating the Kings, the Duke, the state. “And we brought him down!” she exclaimed triumphantly, throwing her head back with a loud, liberating laugh. “Little ranching family brought him down!”

Cecilia Ballí, a former staff writer at the San Antonio Express-News, is now a graduate student at Rice University.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Padre Island

- Brownsville