Featured in the San Antonio City Guide

Discover the best things to eat, drink, and do in San Antonio with our expertly curated city guides. Explore the San Antonio City Guide

Because I am from San Antonio, where preserving the past is almost a religion, I am pretty good at the game of What Used to Be. I can tell you, for instance, what used to be where the Fuddruckers now sits just southwest of Alamo Plaza—my grandfather’s men’s clothing store, Frank Brothers. I can tell you what used to be at the intersection of Mulberry Avenue and St. Mary’s—the stables where, before the golden era of liability lawsuits, I used to rent beleaguered old horses to ride on the trails in Brackenridge Park. Before a luxury high-rise occupied the intersection of Hildebrand and Broadway, Earl Abel’s 24-hour restaurant, where I wooed diners for tips, sat there. There used to be stray cats all over the Alamo grounds, and I remember tiny alligators in an enclosure in the lobby of the Menger Hotel.

These memories, now irrelevant to anyone but me, mark me as a daughter of San Antonio, even though I beat it out of my hometown for college in the seventies with no intention of returning. Sure, I came home for holidays with my parents and later for visits, along with my husband and then our son, and for an assortment of weddings and funerals. But, excluding a few brief detours to other cities, Houston has been my home since 1976.

I fell hard for Houston. When I arrived, the city was in an upturn amid its succession of booms and busts. And it felt so different from where I had grown up. Unlike sleepy San Antonio, Houston was a big, teeming, international city, and over the years it became more so. San Antonio had eccentrics; Houston had larger-than-life characters—ornery oilmen like Oscar Wyatt and flamboyant criminal attorneys like Percy Foreman. San Antonio had silly Fiesta duchesses; Houston had international socialites who hosted Middle Eastern potentates and Princess Grace at restaurants such as Tony’s, where the chef would serve the rich regulars chicken-fried steak, made from fresh veal, at two in the morning. San Antonio high society had seemed closed to all but a select few who had won the generational-wealth lottery; in Houston, the most powerful people in town would take a reporter’s phone call and maybe even invite you for dinner. As I settled into my adopted hometown, I began to think of San Antonio as an old friend I appreciated when we got together but otherwise didn’t think much about.

That was how it went for the next four decades or so. I would come into town and fall into a familiar familial torpor, gossiping and reading at the kitchen table alongside my parents for hours in their high-rise condo, never quite forgiving them for selling the house that we called home for more than thirty years, just down the street. We’d visit one of three beloved restaurants, where everyone ordered the same dishes: green enchiladas at Mario’s (until it closed), sopa azteca at El Mirador (ditto), and the cold lamb plate at the Liberty Bar, an entrée I enjoyed first in the restaurant’s original location, in a badly listing structure alleged by some to have once been a brothel, and then, begrudgingly, in its new spot, in a restored convent in King William. In all these places I took no small measure of joy in seeing faces I recognized: friends of my parents, who always seemed glad to see me, and high school acquaintances with whom I could be glancingly friendly without obligation. But as I took off on Interstate 10 East, I welcomed the surge of returning energy I felt as I got closer to Houston.

That I would ever come to miss San Antonio did not seem possible, because it did not occur to me that I could ever lose it. But then my mother died suddenly from a fall, in 2009, and my father’s worsening dementia required us to move him to Houston, in 2013. Back then, I could not bring myself to sell my parents’ condo. My excuse was that I was too busy working. I was caring for my dad. I was overwhelmed. I simply did not have time to dismantle my parents’ world, two hundred miles away. But I knew there was more to that nondecision.

My brothers had long ago decamped to New York and North Carolina. Dad lived with my husband and me for about three years and then, after my brothers and I finally did sell his apartment, in a cheery bungalow next door until his death in 2018. After that, in what seemed like an instant, the San Antonio that had been ours—the city that someone or other in my family had called home since the 1840s—was no more.

I’d spent the first eighteen years of my life desperate to get out of San Antonio and, over the subsequent decades, treating it with mild condescension, so the profound homesickness that has grown more palpable and powerful since the loss of my father still surprises me. It might have been the enforced exile of a year-long lockdown that allowed my grief and ambivalence to finally soften. As anyone who has dealt with loss knows, grief manifests in strange, unpredictable ways, as customized as couture. The more I stayed away, the stronger the pain and the deeper the longing to return.

Are you going to write about all the losers we went to high school with?” my old friend Susan asked me recently, even before settling into her seat at a restaurant in Alamo Heights. It was my first post-pandemic visit home. Susan and I had not seen each other in years and had not been close since fifth grade, when we were BFFs. Later, she would become one of those people I would run into on San Antonio visits and promise to reconnect with—I’d never get around to actually making a date. In her sixties now, she is tall and willowy and still pretty in the way of so many of the blond, blue-eyed girls I grew up with. Any hard times she’s had don’t show on her face. But her inquiry carried with it some thick, gooey residue from the past.

Back in 2018, the San Antonio Current, an alt-weekly, ran a cover story: “The Burning Question,” which a local would immediately know was, “Where’d you go to high school?” The city was, and still is, so socially, ethnically, and economically stratified that the answer to that question was the quickest way to pigeonhole the responder.

I must now confess that Susan and I are graduates of Alamo Heights High School. If you are not from San Antonio, you may not understand why I would feel sheepish about that, but locally the words “Alamo Heights” connote rich, white, powerful, and privileged. Some of my classmates there were heirs of families whose wealth could be traced to 1845, when Texas became a state. Some bragged about bloodlines that went back to the original Spanish settlers from the Canary Islands in the eighteenth century. Some would inherit sprawling ranches in South Texas that dated back to the Spanish land grants. Others would go on to run some of the law firms, businesses, and banks that have only in recent decades begun to loosen (or lose) their grip on the city.

For most of my childhood, my father worked in my grandfather’s store, and so I, like Susan, grew up with a modest income and knew what it was like to live with my nose pressed against the glass. I was never invited to the Frontier drive-in on the Austin Highway for burgers, and I never got a bulbous chrysanthemum with blue and gold ribbons—much less a date—for an upcoming football game. Life in Alamo Heights then could have been an outtake from The Last Picture Show, with so many Jacys and Duanes that it was almost impossible to imagine, despite my mother’s insistence that I would one day find my place in another world.

I did not come by my antipathy toward the city independently. My mother was born and raised there, as were her father and his mother. Mom made her own frustrations very clear when it came to living in what felt to her, in the late fifties and early sixties, like a very small city. My mother was beautiful and smart, a visionary in the way she could see how things should be: rooms, houses, clothing, artwork, and, unavoidably, children. She would have made a great interior designer or museum curator. But, in her telling at least, there were too many roadblocks to her career-woman ambitions, beginning with her conventional parents who hewed to (and, as Jews, protected themselves by following) the most conventional rules of San Antonio. Standing out would have been dangerous—and not just socially.

My mother escaped from San Antonio by going to a parent-sanctioned Baltimore college. Then she quit school and married someone who must have seemed the antithesis of her father: a darkly handsome, easygoing charmer with an almost preternatural sweetness who dreamed of being a diplomat. His family in Baltimore engaged in heated, sometimes screaming, arguments at the dinner table over politics and world affairs. Their house was packed with books they actually read. His relatives came over to play music in the living room. Undoubtedly there were families that behaved in this manner in San Antonio, but this was a new world for my mother. The family was intellectual, creative, outspoken, argumentative.

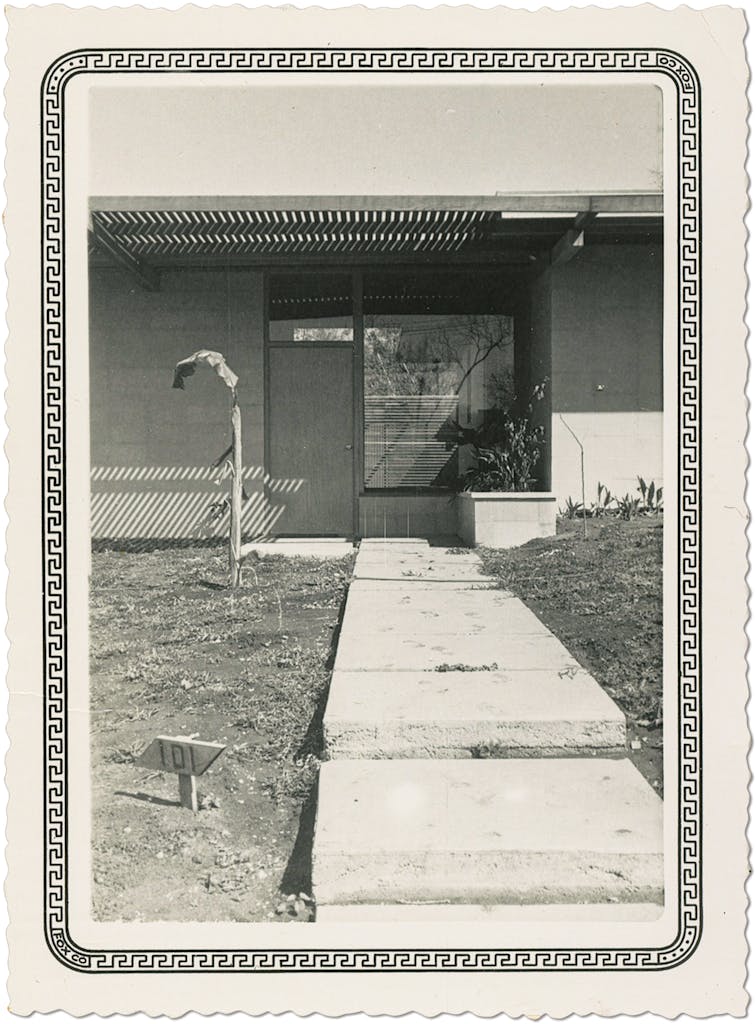

It was also bossy. My mother’s new in-laws, who probably appeared endearingly screwball at first, soon revealed themselves to be as hidebound as Mom’s parents, just with a different veneer. It was this neighborhood, not that one; these friends, not those. Maybe they were trying to save my parents from encountering the anti-Semitism that was spreading at the time—restricted neighborhoods, Jewish quotas for jobs—but I’ve seen pictures of the small, treeless tract house my grandparents approved for the newlyweds in Baltimore. Mom would have been happier in an unplumbed squat near the harbor that she could build to suit. She had exchanged one trap for another, and once she realized there was no more freedom in Baltimore than there had been in San Antonio, the latter probably seemed a lot more appealing. That she and my father saw only two cities as options may have been due to the birth of their first child: me.

They moved back to San Antonio. It was then that being thwarted became the lodestar of my mother’s personal narrative. “Why are you taking a job away from a man?” her father asked when Mom went to work at a bilingual newspaper in San Antonio. In my mind—and in my mother’s frequent retellings—my grandfather’s query, and the many similar inquiries that followed, became a distant early-warning system, with my mother clanging the alarm bells: get out while you can.

I was shipped off to the East Coast for annual summer visits with my paternal grandparents from the time I could walk—not just to see Fort McHenry but to visit Greenwich Village and to be carried by different tired horses (this time pulling carriages through Central Park) and to hike the hills of Virginia with my aunt and uncle. The message, sometimes stated—“This reminds me of San Antonio,” my paternal grandmother would say when we were driving through the most faceless Baltimore suburbs—and sometimes not, was that the Eastern seaboard was more sophisticated/more intellectual/more better than Texas in just about every way, and at the time I wasn’t inclined to disagree.

During my high school years, I spent most of my time skipping afternoon classes, smoking cigarettes, and watching TV. On weekends I took late-night walks through the neighborhood with my best friend Jill, talking about what we would do when we moved to Greenwich Village.

We just didn’t fit in the only milieu we knew, one that was as wedded to rites and rituals as the Windsors’ and as devoted to self-perpetuation. We didn’t want what the people around us wanted: camp at Longhorn or Mystic; vacations at the coast, which then meant either Port Aransas or Rockport; a house in one of three neighborhoods deemed acceptable; a marriage to a classmate or neighbor that felt like a fait accompli. That there might have been another way to live in our hometown was, by the time we were grown women with husbands and families, inconceivable.

It wasn’t until the mid-nineties or so, when our son, Sam, was past the toddler stage, that I began to see San Antonio somewhat differently. Here, I would tell him, driving by Cambridge Elementary, is where your mother and your grandmother went to school. There, I would say, indicating a wholly innocuous shopping center, is where we used to eat watermelon at the Ize Box on our walks home from school. Here is the house on King William where your great-grandfather had Sunday lunch with his family. “Would you like to visit the Alamo? Ride the Brackenridge Eagle train through the park?” I would ask Sam hopefully. For reasons that had less to do with nostalgia and more to do with identity, I wanted him to see and feel all the things that once made up the background of ordinary life in San Antonio for me: the heady aroma of the mountain laurel trees in bloom; the ubiquitous tejano music; the effortless interchange of Spanish and English; the way the clean, sweet summer air warmed the skin; the greasy, velvety flavor of a perfect cheese enchilada.

I told him stories about his grandfather’s former employer, a florid-faced scion who looked and spoke like John Barrymore and had a swimming pool filled with icy creek water and a Chinese junk floating in the deep end. I wanted to take Sam to the straight-out-of-Giant Christmas Day party given by one old ranch family—a party that my brothers and I loathed for its timing and dress code—where the tables were laden with silver platters of homemade tamales and the bar was stocked with a small sea’s worth of bourbon. By then I was pushing forty and understood that so many of those things—big and small, kind and cruel—had made me who I am.

And I was beginning to experience the kinds of bigger losses that make a person want to hold on, tighter, to what remains. I’d lost my grandparents, whom I had dearly loved despite or because of their funny failings. I’d lost close friends to disease, or just distance. And then I lost my mother, after a fall outdoors on a searingly hot day while my father was taking a sentimental journey with my son to San Francisco. My husband and I had come to San Antonio to keep her company, and we slept in, blissfully unaware, until a neighbor pounded on the door of my parents’ condo to tell us the ambulance had taken her away.

I was beginning to experience the kinds of bigger losses that make a person want to hold on, tighter, to what remains.

Years later, in the time between my mother’s death and my father’s decline, I went home more often, ever the attentive daughter. Those visits were infused with an oppressive sadness until my father, thankfully, found new companions. The thought of all those nights he’d dined alone in restaurants he’d previously gone to with my mother was almost too much to bear, even though I knew he charmed all the waitresses.

The days when he was able to have coffee on the West Side with Henry Cisneros’s uncle or take trips to the symphony with longtime friends had slipped away. And soon he could no longer comfort himself alone in the apartment he had created with my mother.

Those who have cared for aged parents know there comes a time when there are no good choices. Once Dad’s decline made it impossible for him to live in San Antonio, he adapted fairly quickly to Houston. The man who had once devoured foreign affairs news seemed content watching Antiques Roadshow with his caregiver. But it was never lost on me that I had wrenched him from the place he loved, where someone was always, always so glad to see his luminous smile. And then he was gone too, and my trips to San Antonio waned for reasons that were probably obvious to everyone but me.

I did visit every once in a while, but with a growing list of personal prohibitions. I did not look up childhood friends, even though I promised to do so when they reached out. Cappy’s, a local hangout started by an Alamo Heights alumnus and former neighbor, was off-limits; it was the place my remaining family had gone the day after my mother died. (We ran into one of my mother’s many frenemies, and the awkward job of explaining her absence fell to me.) Ditto the so-called Gucci B, the first of H-E-B’s upscale Central Market stores in San Antonio, which was routinely frequented by old friends and neighbors. Any place where I might bump into someone who wanted to tell me how much they had loved my mother or father or how grateful they were for my parents’ contributions to the city—building a new library, working for local and state politicians, supporting San Antonio artists, and more—was to be avoided. Under no circumstances was it possible for me to drive by our old house, the place that overlooked the Olmos Basin, where, on the roof outside my window, I had smoked packs of Merit cigarettes and dreamed of the day I would live in New York. Visiting the cemetery where my great-grandparents, grandparents, and parents were buried was out of the question.

Instead, I trolled real estate sites, checking out neighborhoods I had once known. I wasn’t looking for a house to buy; when we’d sold my parents’ apartment, I had been added to the realtor’s email list, and I’d been drawn in by streets and neighborhoods I’d once known. I was virtually easing my way back into town, which seemed easy and safe enough, until it wasn’t. I stumbled upon one ranch house in Castle Hills that looked oddly familiar and, seconds later, realized it had once been my grandmother’s. I clicked through, noting how little had changed inside, filling in what was missing: the tropical fish tank in her breakfast nook, the bathroom vanity filled with sea glass and shells I had so loved as a child. My luck was poorer in my family’s house near the Olmos Dam. It had been bought by a much wealthier family who had made it bigger and grander. I got lost trying to get from the kitchen to the living room in the way so many visitors to San Antonio get lost on its twisted, irrational streets.

When I thought about going back in person, the larger problem, or so I told myself, was that there was no place for me to stay. This was not true, of course. Friends offered lovely spare bedrooms, and there were newish boutique hotels, such as the Hotel Emma and the Hotel Havana, which in any other city would have been irresistible. But I alleged that the Emma was too pricey and the Havana too close to what used to be the Municipal Auditorium and is now the Tobin Center for the Performing Arts, a name that still evokes painful memories of the time my father was pushed out of his last job there, one he held for thirty years. (One could argue that my father, then seventy, had reached a reasonable retirement age, but loyal daughters can be impervious to reasonable argument.)

And so I stayed in Houston, waiting for the clock to run out on my memories.

With no one to care for, far fewer distractions, and no place to go during the pandemic year, I found the strength to go through some of my parents’ most personal things: diaries, papers, and letters. I had shoved them into one battered old briefcase as we were cleaning out the apartment and had stuck them in a corner in Houston, mentally labeling the contents “Potentially Painful, to Be Avoided.” But with the passage of time, I was at least ready to mourn in bits and pieces. Literally.

I don’t know what I had expected to find. Part of me hoped for a hint at some dark family secret that I could explore for a potential best-seller, but instead I just found . . . my parents. I was struck by a letter my dad had written to his father-in-law before he and my mother moved back to San Antonio. “Marie and I are still getting acclimated to living in Baltimore,” he wrote. “I think if we’re able to get my folks off our backs, we’ll be okay.”

Next, I tackled my mother’s scrapbooks from the forties, expecting to find evidence of a lonely, misunderstood young woman. What I found was page after page of high school party invitations, pictures of Mom laughing with her pretty, flouncy-haired girlfriends, and dance cards overloaded with the signatures of local boys whose names I’d known all my life. An even older album showed her happily stroking a calf on a farm in Hallettsville that I would visit decades later, accompanied by her same beloved babysitter. There were shots of an eleven-year-old Mom on horseback, in deep concentration, her hands holding double reins while she sat proudly on an English saddle—something I would do just as proudly, and, for a Texan, inexplicably, as her eleven-year-old daughter.

Maybe life in San Antonio was as backward and frustrating as my mother told me, but as I turned those fragile, yellowed pages, I understood that for all her carping, something had told her to convince her newly minted husband that his home of Baltimore would never be hers. She was losing track of who she was, and she needed to be back where she was known and where she was loved.

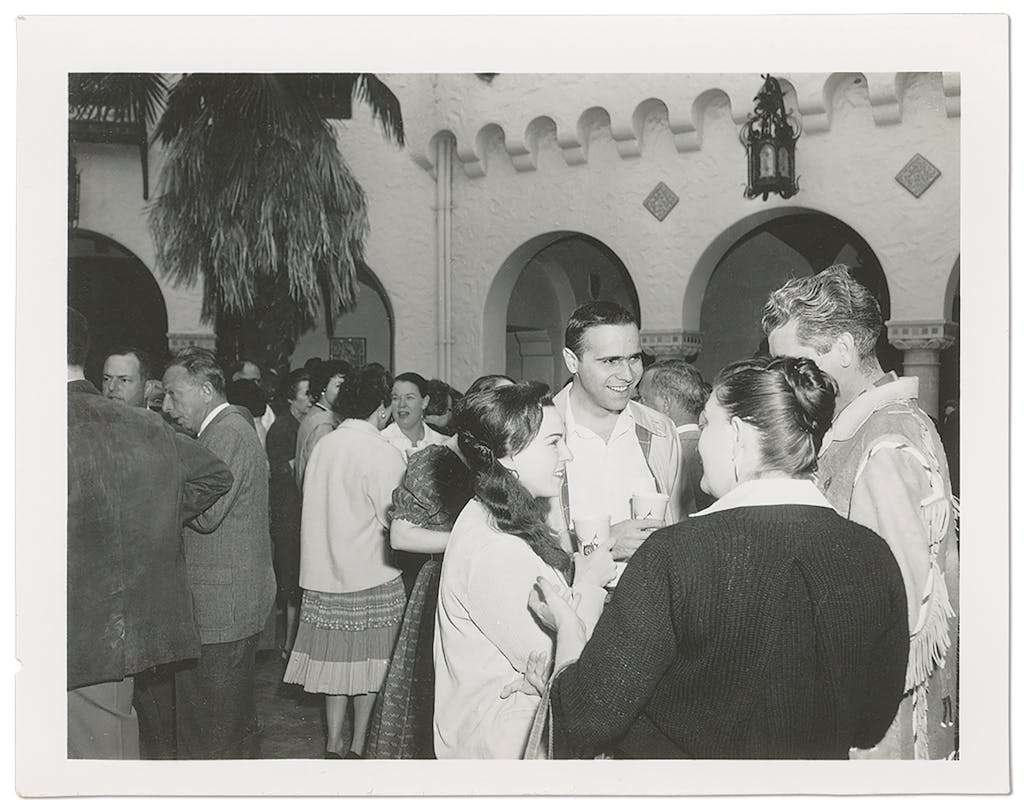

Maybe I did too. After the Moderna vaccine freed me from lockdown, as I was itching to go somewhere, anywhere, I gutted up and went back home—my original home. As I did when my parents were alive, I made a beeline for the Pearl, the development that incorporates the old Romanesque brewery transformed into the elegant Hotel Emma and where the stores and restaurants reflect the best of the city’s evolution from backwater to metropolis. I grabbed a quesadilla and an agua fresca at La Gloria and parked myself on a brightly painted metal chair near the river. There, I silently communed with the native plants my mother had taught me to identify. I marveled at Dos Carolinas, which sells $200 custom-made guayaberas, and Feliz Modern, which offers serape stickers in the shape of Texas, Frida Kahlo puzzles and blankets, and seasonally appropriate earrings shaped like cicadas.

After dithering over lodgings, I opted for my friend Katy’s house, an inspired Alamo Heights cross between a hacienda and a Moorish casbah, which sits between my parents’ retirement high-rise and my adored old house nearby. I slept just fine, waking to the sun streaming through the branches of the ancient live oaks just outside Katy’s guest-room window, which allowed me to imagine for just a few groggy seconds that I was back in my old room with its nearly identical view.

I felt the ghosts floating nearby, in particular, those of two teenage girls with hippie hair and bell-bottoms, plotting their departures.

Of course, I knew who had lived in that house before Katy and her husband, Ted, had moved to Alamo Heights. On our after-dinner walks I could tell my Houston-raised friend who used to live in each of the houses we passed. The Pridgens here, the Tuckers there, the Lights up the street, Jill just around the corner. As Katy and I walked and talked, I felt the ghosts floating nearby, in particular those of two teenage girls with hippie hair and bell-bottoms, plotting their departures as if they were in control of their destinies and blissfully unaware that they didn’t, really, have all the time in the world.

It was that thought that finally got me to the cemetery on that first visit back to San Antonio. I found the old Jewish graveyard northeast of downtown, pulled in past the rusting iron fence, and parked when I sensed I was close. Searching for my family plot, I strolled past the headstones of so many people I used to know: women my grandmother had played cards with, men my grandfather had sold suits to, old family friends to whom I still owed thank-you notes for wedding presents.

I didn’t stay long at my parents’ graves, even though my father had paid for a sturdy bench after my mother’s death. My eyes began to burn, and a heavy, sleepy sadness overtook me. I could always come back, I told myself.

I searched the ground and picked up some rocks. Bowing to a nearly lost tradition, I placed one on each grave: of my great-grandparents, my grandparents, and my parents. Just so someone would know I was there.

This article originally appeared in the July 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Hello Again to All That.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- San Antonio