When Andrea Lozano, a 31-year-old Mexican food blogger, found out Taco Palenque had arrived in Monterrey, Mexico, she knew she wanted to review it. Taco Palenque tasted of her childhood. It was her family’s go-to restaurant during annual shopping pilgrimages to Laredo. The Monterrey location was almost empty that Friday night in late August 2023, likely due to the many street repairs in the area, but that didn’t deter Lozano. She got two fajita tacos, one chicken and one beef, and a flour quesadilla with chorizo. Something was missing that had nothing to do with the fact that one of the tortillas was cold and the beef was slightly charred. “I didn’t feel the magic,” she said.

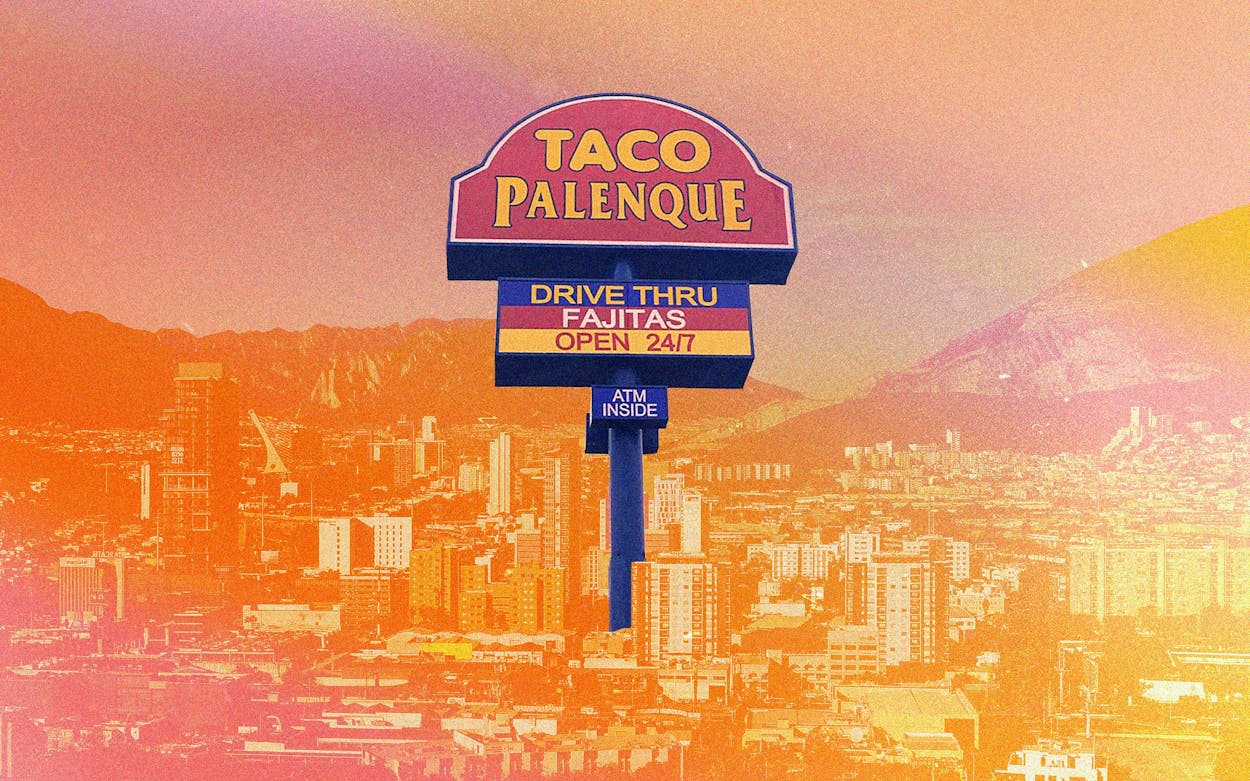

Taco Palenque opened its first Monterrey location in April 2022, bravely undertaking the task of bringing a chain selling Tex-Mex, Mexican, and norteño food to the cradle of tacos. Taco Bell tried it in 1992 in Mexico City and failed. Back then, the idea of opening a U.S. taco chain in Mexico was ludicrous and offensive to many, and it still is to taco purists and nationalists. But Taco Palenque is not Taco Bell, and Monterrey is not any Mexican city. Regios, the demonym for people from Monterrey, are often more familiar with their Texan neighbor than they are with many of Mexico’s southern states. If Taco Palenque triumphs in Monterrey, it might prove how archaic the debate over the authenticity of tacos has become.

Monterrey is proud of its strong ties with Texas. Regios are known for their secessionist sentiments, which are more of a joke but occasionally make headlines. Monterrey doesn’t share a border with Texas, but that hasn’t stopped the city from sharing a long history and culture with the Lone Star State. Both areas share an appreciation for H-E-B and barbecue, existed briefly as rogue republics in the nineteenth century, and depend on large highways, although Monterrey’s are more run-down and dotted with potholes. Laredo has a visitors center in Monterrey, and it’s not uncommon to see billboards inviting regios to shop in South Texas. Monterrey’s proximity to Texas is evident everywhere, from the UT bumper stickers and Buc-ee’s merchandise to the fascination with Whataburger.

When Taco Bell first opened in Mexico, in the 1990s, with a location in Mexico City, renowned Mexican cultural critic Carlos Monsiváis described it as “like bringing ice to the Arctic.” The American fast-food chain failed and closed less than two years later. In 2007 Taco Bell opened a location again, this time in Monterrey, in a commercial strip that also housed an H-E-B. Another followed a year later.

“I mean, how stubborn are gringos that they are so blindly determined to sell us tacos in taco land!” reads a 2008 food editorial in El Norte, Monterrey’s main local paper. Skepticism existed on both sides of the border. On The Daily Show, Jon Stewart mocked Taco Bell’s Mexican incursion, and Fortune magazine included it in 2007’s “101 Dumbest Moments in Business.” Monterrey’s Taco Bells closed in 2009.

Taco Palenque has a few differences from Taco Bell. Its founder, Juan Francisco Ochoa Sr., is Mexican and is a known figure in Monterrey as the owner of El Pollo Loco, Taco Palenque’s parent company. El Pollo Loco’s fired-grilled chicken has been a Monterrey fixture since 1979. What Laredo is to Taco Palenque, Monterrey is to El Pollo Loco. So great is the Ochoa’s pull that the governor of the state of Nuevo León, Samuel García, attended the 2023 opening of Taco Palenque in San Pedro Garza García, the Monterrey metro’s wealthiest zip code.

“For restaurants to really take off in Monterrey they need to come disguised as gringos,” said José Perales, a journalist from Monterrey who loves all things Texan. As a kid he preferred the Nesquik chocolate powder his parents bought in Laredo over the one sold in Mexico, just as he now prefers Hill Country fare over the Mexican equivalent. Perales, who went viral this year for calling Nuevo León a country, believes Taco Palenque will work in Monterrey because the city is already very “Texanized.”

Many restaurants in Monterrey have names in English, such as Holy Cow, Pound, and Burger Nation, or with English words like “house,” “grill,” and “room” in them. Even taquerias do it. Americana, a hip taqueria in San Pedro, has English advertising (“No ticket, no taco”) and uses Spanglish in its marketing.

Monterrey is also flooded with American chain restaurants, and regios love them. Growing up, Perales didn’t need to cross the border in order to reach American fast food. His parents would take him out to eat at Mexico’s second McDonald’s, on Gonzalitos Street, every Saturday.

In the span of one year, Taco Palenque grew to three locations in Monterrey’s larger metropolitan area, and Perales believes it’s due in part to regios’ fondness for Tex-Mex. This is not to say Taco Palenque doesn’t have its detractors. Most comments criticize Taco Palenque’s American origins, but others point out its pricing as a turnoff. A pirata (a carne asada taco with cheese) from a local vendor costs on average about $4, compared to Taco Palenque’s $6 pirata. On a TikTok creator’s review of Taco Palenque, users left comments like “Taco Palenque arrived in Mexico, a company that sells Mexican food that is not even from Mexico” and “Tacos are on every street corner of Mexico . . . depending on the stand, from 6 pesos up to 15 pesos [per] taco.”

Miguel Cobos, cofounder of Vaquero Taquero, a taqueria in Austin, believes Mexicans are no longer in a position to defend the taco’s authenticity. Tacos are a product of globalization now, as are burgers, pizza, sushi, and orange chicken. Just as Mexican taquerias like Tacombi are selling tacos in the U.S., there are Mexican burger joints like the Food Box, from Monterrey, selling burgers in San Diego. It’s in this context that a taco chain from Texas making its way just a few hours south is not such a wild idea.

Cobos, who was born in Monterrey but grew up in McAllen, thinks Taco Palenque should be judged by its quality and flavor, not its origin. But farther away from the border, such as in Mexico City, where 94 percent of the population lives five minutes away from a taqueria, the relationship with U.S. products is more fraught.

When Los Bernardino’s, a Mexican restaurant selling hard-shell tacos, opened in Mexico City in early 2023, it was vandalized with an insult against gringos. In this case, the hate against the hard-shell taco was less a rejection of the food and more a reflection of the tensions that gentrification provokes.

In Monterrey, the line where Mexico ends and Texas begins is much more fluid. Regios get Tex-Mex in ways chilangos, people from Mexico City, never will, as the “Mex” in Tex-Mex is not referring to all of Mexico, Perales said. “It isn’t Oaxaca, Chiapas, or Tabasco; it’s about this part, the northeast.” Perales described the differences between Monterrey’s cuisine and Mexico City’s: “There are no flour tortillas; I tell you because I suffered it firsthand,” he said about the years he lived in Mexico City. Then there are the beef cuts that are hard to find in fonditas, the diner-type restaurants that abound in Mexico City. Barbacoa from Monterrey is closer to San Antonio’s version than it is to Mexico City’s, which uses lamb instead of beef, he said.

So maybe it is possible for Taco Palenque to thrive here, given regios’ fondness for Texana and Tex-Mex. Lozano, the food blogger, is willing to give it another chance. It is no longer the place in Laredo that mesmerized her with its salsa bar and made her feel at home. It is no longer the place where she would run into family acquaintances. It’s something new that she’ll have to discover, if Taco Palenque stays in Monterrey long enough.