Fernando Garza is dressed in a blue-and-white striped button-down shirt, neatly tucked into his jeans. His hair is salt-and-pepper, and he’s holding a cup of calcium hydroxide. The 58-year-old sprinkles the white powder, also known as slaked lime or cal, down the middle of a five-foot-tall tank filled with water. Thousands of dried white corn kernels are settled at the bottom. Garza, a manager at Sanitary Tortilla Manufacturing Company in San Antonio, picks up a metal paddle and submerges the instrument into the trough. He stirs quietly and deliberately, but the water does occasionally splash out of the container and onto the tortilleria’s floor. The dissolving of the cal creates the alkaline solution in which the corn is cooked and steeped. This process loosens the pericarp, or hull, from the inner part of the corn kernel and releases essential nutrients like niacin (vitamin B3), riboflavin, and calcium to create a highly beneficial food.

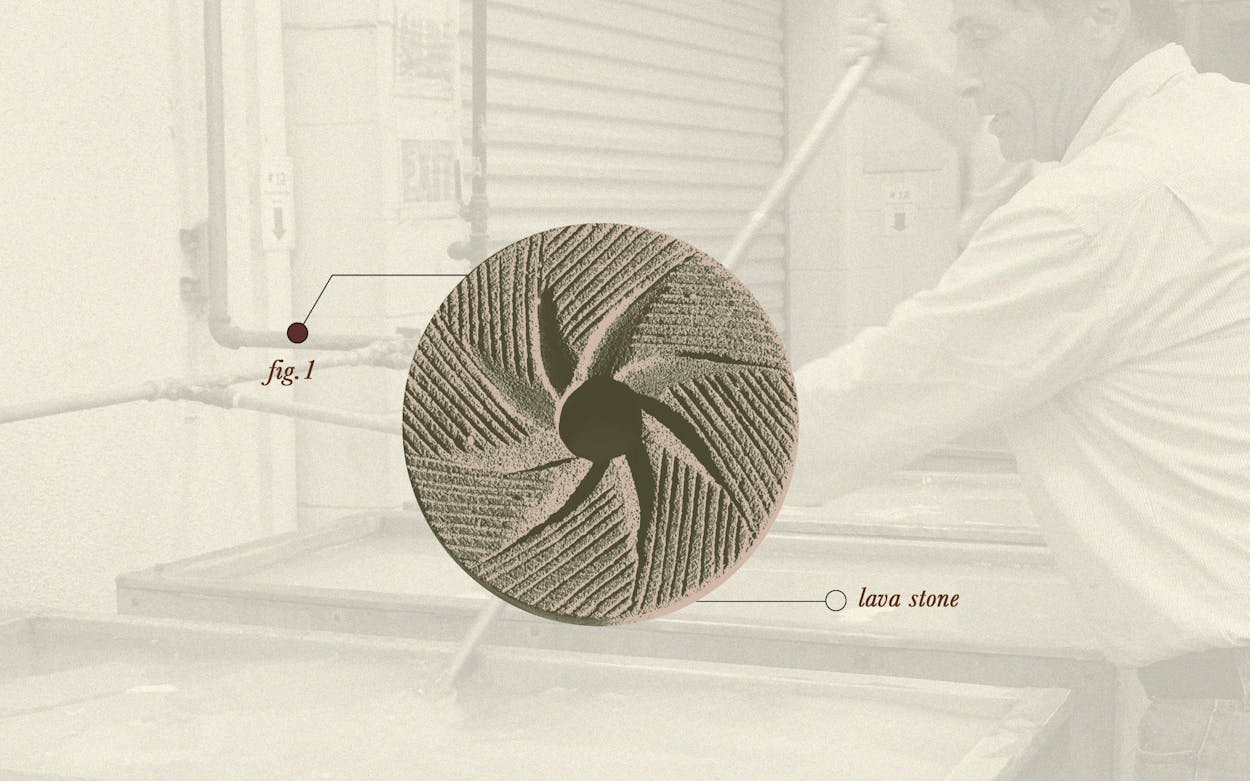

This is nixtamalization, invented by ancient Mesoamericans more than 3,500 years ago—originally, wood ash was used in place of cal—and the transformed corn is called nixtamal. The product is run through a molino (mill) equipped with two lava-stone blades that grind the corn into a dough, or masa, which is made into myriad preparations: sopes, huaraches, tlacoyos, quesadillas, infladitas, and the most elemental of them all, tortillas. In Mexican food, nixtamalization is the foundation of everything. And it involves only three ingredients: corn, water, and cal. There are no preservatives, so quick eating is crucial. The process releases a rapturous aroma of sweet, fresh corn. And corn is the bedrock of Mexicanness, a staple that laid the groundwork for a culture that influenced the Americas, Texas, and all of the U.S. borderlands. It changed a huge swath of the world. At Sanitary Tortilla, nixtamalization is described as “like the Aztec way.”

Garza, a chemical engineer by training, is carrying on this tradition at the oldest continuously operating tortilleria in San Antonio. He answers my questions politely but briefly, intent on his work, and seemingly overdressed for a hot day in the back of the tortilla factory that was established in 1925. To one side of the several nixtamal tanks lining a wall is a garage door through which Sanitary Tortilla receives deliveries of American corn. In the darkened room beyond where we’re standing are large mechanical tortilladoras. The automated machines creak and hum as they produce thousands and thousands of fresh corn discs. Some are delivered to retail clients; others will be sold at the storefront counter. Normally, the nixtamalization process begins in the mid-afternoon and takes a full 24 hours, from the mixing of the cal to the finished tortilla.

“But it really depends on the day,” says Sanitary Tortilla owner Luis Garcia. “Sometimes we come in at 5 a.m. to make the masa.” Garcia’s employees produce on average 2,500 pounds of masa daily. It’s a laborious process, but nixtamalization’s benefits are worth the effort. “The flavor is better and the tortilla is much, much healthier,” Garcia says.

Eighty miles northeast in Austin, El Naranjo co-owner and executive chef Iliana de la Vega manages the same work. Her restaurant doesn’t need as high a volume of tortillas as the factory, but the process still takes nearly as long. “Let’s say that the average time to nixtamalize the corn is about nine and a half hours,” she says. “Then rinsing and rubbing is another hour and a half. One hour for grinding, about fifteen minutes for kneading, and then making the testales [masa balls], which will depend on how many tortillas are being made.” All in all, de la Vega says it takes her fifteen hours to complete a batch of tortillas.

Andrés Garza studied anthropology at the University of Texas before working in the kitchen of Nixta Taqueria, a modernist taco spot, that nixtamalizes in-house. He moved home to the Rio Grande Valley a few months ago to establish Neighborhood Molino, a tortilleria and milling operation in McAllen. When asked to describe nixtamalization and nixtamal, Garza doesn’t hesitate. “It’s alchemy,” he says emphatically. Yes, there is science behind the process and product, but it’s magic too. Cooks must master the difficult craft of altering the chemical balance according to the preparation and type of corn. There are approximately sixty varieties of heirloom Mexican corn, not to mention the myriad heirloom corns native to different parts of the Americas, as well as proprietary genetically modified corn. “If we get Peruvian corn, if we’re working with American corn, then we do play a little bit with the pH balance,” says Emmanuel Chavez, owner, tortillero, and chef of Tatemó. The Houston tortilleria, molino, and pop-up sells masa by the pound, as well as masa-based dishes and tortillas, by preorder and at area markets. A trick Chavez uses during production is to put the lava grinding stones on ice to cool. This prevents the corn from cooking while being milled.

Nixtamalization has been sustained for thousands of years, primarily by women. Traditionally, the matriarch of the house would work around the clock in the kitchen to produce not only nixtamal but whatever dishes could be made by grinding the corn on a metate, a three-legged volcanic rock tablet. Water was added as needed, and a rolling pin called a “mano” would then be applied to the corn for grinding into masa. It was these women who created Mexican cuisines into the wonders that it is. “If nixtamal did not exist, we Mexicans wouldn’t be here,” de la Vega says. “It is the pillar of the Mexican diet, as is rice for Asians and wheat for Europeans.” As the old Mexican saying goes, “Sin maíz, no hay país.” It means, “Without corn, there would be no civilization.”

Yet for nearly a century, nixtamalization has been in danger of disappearing. Industrialization shifted the production of nixtamal and masa to mechanization and masculinity. Men took the work into storefront molinos (millers) and tortillerias. In the mid-twentieth century, Gruma and other corporations scaled up production of tortillas with brands of dehydrated corn dough such as Maseca, chock-full of preservatives to maintain the commodity’s shelf stability. When water is reintroduced and masa formed for tortillas, the finished product carries chemical, metallic notes at worst, or the tortilla is flavor-neutral at best. International trade agreements (saludos, NAFTA) also decimated corn farming in Mexico and nearly destroyed heirloom corn in favor of GMO corn.

After falling in love with nixtamalization and nixtamal while traveling in Mexico, El Paso–Juarez native Alejandro Borunda, co-owner of newly opened Taconeta, returned home and was disappointed. “I went to the tortillerias I grew up going to in Juarez and, to my surprise, they were all using Maseca,” he says. Borunda chalks up the prominence of Maseca along the border to the popularity of the flour tortilla in Northern Mexico. He felt a responsibility to showcase nixtamal at Taconeta when the restaurant opened during the pandemic. “It’s a thing that has been going on since the Aztecs, but it means so much that I felt like there was no other choice.”

Emiliano Marentes, chef and co-owner of Elemi, which is also in El Paso, agrees. Nixtamalizing corn in-house isn’t just about making better food, it’s also about reconnecting with Mexican cultural identity, he says: “It’s about getting back to our roots.”

Nixtamalization’s profile has increased in the last few years as modernist Mexican restaurants and taquerias have embraced heritage, artisan techniques. You can find this process at places such as Nixta Taqueria, Suerte, El Naranjo, and Comedor in Austin; Xochi in Houston; Salomé on Main in McAllen; La Resistencia in Dallas; and Taconeta and Elemi in El Paso.

Tatemó’s Chavez believes it takes a special kind of person and ingrained passion to take on the responsibility of nixtamalization and masa. “Does anyone really want to get up at 5 a.m. and do this every day constantly for the rest of their lives?” he says. “No. You do have to be born with it. … You have to see the bigger picture. We’re not just making tortillas, we’re restoring the value of our culture. We’re reintroducing that corn. It’s powerful. It’s a staple. It’s nutritious. It’s delicious. It’s the whole package.” Nixtamalization is everything.

- More About:

- Tex-Mexplainer

- Tacos

- Mexican Food