It might not be well-known to the public, but the devastated restaurant industry is clinging to what those in the business say is their last best hope for surviving the pandemic: the $120 billion RESTAURANTS Act, a bipartisan federal grant program that was introduced in Congress in mid-June. In Texas, two well-known chefs and restaurateurs are doing what they can—in between trying to save their own businesses—by calling lawmakers and getting support for the measure.

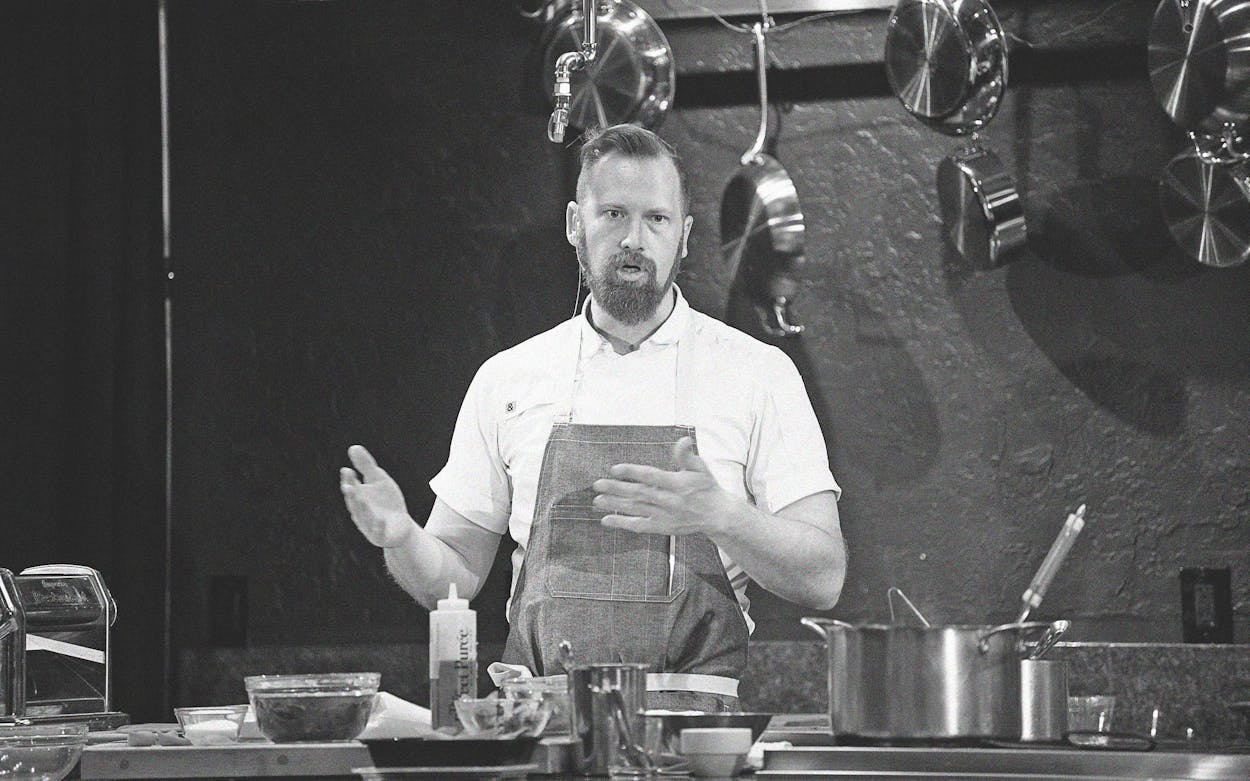

Taking the lead is Austin chef Kevin Fink, whose four restaurants include Emmer & Rye and Hestia. “A lot of restaurants are just holding on to see if this relief effort has legs,” he says. “If the bill doesn’t make it, you will see a lot of them go under right away. I don’t have an exact percentage of those that could fail immediately, but I’ve talked to owners who are already there.”

Fink is one of six Texas members of the newly formed Independent Restaurant Coalition, a nonprofit 501(c)(4) organization made up largely of chefs and restaurant owners. Joining Fink on most calls is well-known Houston chef Chris Shepherd. Active behind the scenes are Houston bar owners Alba Huerta and Bobby Heugel, Fort Worth chef Tim Love, and San Antonio chef Rico Torres. At the national level, the group is led informally by New York chef Tom Colicchio, of Top Chef fame, who emerged early on as a passionate spokesperson for the industry. Others include José Andrés, famous for World Central Kitchen’s disaster-relief efforts; Washington, D.C., chef Kwame Onwuachi; Charleston’s Sean Brock; and Los Angeles baker Nancy Silverton. The coalition of cooks and owners are counting not only on their powers of persuasion but also on the fact that many senators and representatives have fond memories of birthdays and anniversaries celebrated in their restaurants.

They are speaking up on behalf of the RESTAURANTS Act (Real Economic Support That Acknowledges Unique Restaurant Assistance Needed to Survive) because the aid that many of them received under the Paycheck Protection Program (part of the CARES Act) is quickly running out.

So is time. Fink estimates they have about a week to make a final push. If they don’t persuade enough members of Congress that the restaurant-relief measure should be rolled into the next massive aid package, its chances of passage drop considerably. Right now, Congress is scheduled to begin its summer recess after August 7, although that could change.

The backers of the RESTAURANTS Act prefer it to more general aid—such as what’s in the $1 trillion HEALS Act proposed by Senate Republicans or the $3 trillion HEROES Act from House Democrats—because it has been designed to fit the specific needs of the industry. They are wary of broader aid provisions because the initial PPP was not a particularly good fit for them, focusing on payroll when the industry actually needed more help with overhead and supplies. (Owners admitted that they found busy work for idle employees just to use up the money. Some actually gave it back.)

The ad hoc lobbyists are a star-studded cast of 125 industry standouts—including Beard award nominees and winners—but they represent independent restaurants of all types across the country. If the bill passes, any eating place from a taqueria to a mom-and-pop cafe to a ramen shop would be eligible for a grant, meaning the money would not have to be repaid. The only operations excluded would be publicly traded companies and chains with more than twenty locations. The bill has numerous hospitality-related supporters, including American Express, Coca-Cola, and Delta Air Lines; the National Restaurant Association and the Texas Restaurant Association back it as well.

The 36-year-old Fink spends hours each day, and sometimes well into the night, on phone and Zoom calls, even as he tries to manage the grim situations at his own businesses. Sales at Emmer & Rye, his popular heritage-grain-focused restaurant in downtown Austin, are down 60 to 80 percent. “We’re only doing pick-up and patio seating,” he says. “We used to have thirty employees; there are now ten.” He and his team are also grateful for a contract to make lunches for an Austin Independent School District program to help feed students in need. All the while, though, “desperation and anxiety are growing every day,” he says. “You feel them like a weight every morning when you wake up.”

Fink has found strength and solidarity in working with 47-year-old Shepherd. Although both are persuasive talkers on their own, they usually make calls together. Over time, the two have fine-tuned their message.

When they talk to many Democrats, for example, Fink says, they stress the human connections. “We talk about the act in terms of the employees it can get back to work,” he says. They emphasize that it supports families, and they stress the place of restaurants in a community’s economy. When they’re talking to a Republican, or a fiscal-minded Democrat, they are more pragmatic. “We underline that this money would just be a bridge to get a restaurant back on its feet,” he says.

When he senses an opening, Shepherd jumps in with a personal story: “I tell them I don’t normally get scared, but I’m scared,” he says. “Before COVID, we were doing 260 or 280 covers on a weekend night” at Georgia James, his Houston steakhouse. Not anymore. “One Saturday in July, we had exactly twenty reservations.” He adds, “The main thing keeping us afloat right now is H-E-B, which is letting us sell our [take-and-bake] entrees in sixteen of their stores. We have a crew that just does that.”

The two also draw on a list of talking points prepared by an independent economic research firm hired by the coalition. Among them: If the bill passes, it could help generate $15.3 billion in economic benefits for the state as well as save Texas $2.7 billion in unemployment benefits and insurance taxes. Nationwide, $120 billion invested now could ultimately return up to $271 billion in economic benefits to the country and reduce unemployment by 2.4 percent.

At some point, they definitely mention that the bill has more than 140 cosponsors in the House (including at least six from Texas: Henry Cuellar, Veronica Escobar, Colin Z. Alfred, Lizzie Fletcher, Sheila Jackson Lee, and Marc A. Veasey, all Democrats). In the Senate, it has twenty cosponsors, including Senator John Cornyn.

Cornyn is regarded as key. “He’s one of the ten most powerful senators,” says Fink. In June, Cornyn co-introduced a complementary bill, the SERVE and CARRY Act, which would enlist restaurants in hunger relief programs. Fink also spoke with Senator Ted Cruz’s representatives. He says they told him that the fiscally conservative lawmaker prefers broader, nonspecific legislation but will not oppose the RESTAURANTS Act.

For the next several days, Fink and Shepherd expect to be on the phone even more, talking to politicians and anyone who might have an inroad with them. He encourages members of the public to urge their elected representatives to support the bill. If the RESTAURANTS Act doesn’t happen, there won’t be any second helpings.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Chris Shepherd

- San Antonio

- Houston

- Fort Worth

- Austin