Ty Phelps leans over the hand-carved mesquite bar and points to a just-emptied tulip-shaped tasting glass.

“That was tradition,” he says.

The snifter had been filled with a pale golden whiskey called Revenant Oak, a faithful rendition of a single-malt Scotch—earthy and subtle, with a lingering wisp of peat smoke. If we hadn’t been standing in the tasting room of Phelps’s Andalusia Whiskey Company, off U.S. 281 in Blanco, it could have been mistaken for the product of a centuries-old distillery in the Scottish Highlands.

Phelps, a sinewy and intense 42-year-old, moves his hand toward the next glass, which is still full. This whiskey is darker, a caramel-colored liquor that sparkles like a piece of amber in the afternoon sunlight.

“This, we feel, is a little more innovative,” Phelps says.

This is Stryker, an original concoction he’s dubbed his “backyard barbecue whiskey.” Like Revenant Oak, Stryker is made entirely of smoked malted barley. Both whiskeys are fermented with brewer’s yeast, distilled twice in a copper pot still, and aged in wooden barrels for two years inside the metal shipping container that serves as Andalusia’s utilitarian rickhouse. But where Revenant Oak evokes the moors and lochs of Scotland, Stryker has been conceived with more local DNA. Instead of using imported Irish peat to smoke the malt, as he does for Revenant Oak, Phelps smokes Stryker’s malt by burning a pitmaster’s blend of oak, apple, and mesquite. And instead of aging Stryker in used oak barrels, as is the custom with most single malts, Phelps uses new oak barrels, giving the whiskey some of the bigger, woodier character of bourbon.

The result is a whiskey that’s smoky without being ashy, spicy without bludgeoning the tongue. It clearly owes a debt to Scotland and Kentucky, but with its firewood smoke and Hill Country roots, it tastes like something new: an authentically Texan whiskey. And it’s all the more authentic because it has been manufactured from grain silo to tasting pour by a tiny team using largely hand-me-down equipment, right there on the Phelps family’s sheep and cattle ranch.

On the hot July day I spent with Phelps, I walked onto Andalusia’s aggressively un-climate-controlled production floor a little after 9 a.m. to find fifty-pound bags of barley stacked against a wall, wrenches and fasteners hanging from a pegboard, and not a single screen or digital readout in sight. (Monitoring computers are commonplace in larger distilleries.) The place looked more like a mom-and-pop bicycle repair shop than a commercial distillery, and the work taking place was sweaty and unmechanized. Phelps, his business partner, Tommy Erwin, and their only production employee, a 26-year-old former roughneck named Hunter Anderson, stirred Grape-Nuts-like slurries of malted barley, tasted clear distillate as it recondensed from vapor, and patched a leak in their copper pot still with rye flour (“an old distiller’s trick,” Phelps told me). In a small air-conditioned room adjacent to the production floor, Phelps’s wife, Ericka, was sealing, capping, and labeling every bottle by hand, a task that would be laborious for anyone but is particularly so for Ericka, because she suffered a stroke when she was thirty and now can use only her right hand. As Phelps showed me the shed where he smokes his barley, he summed up his approach to marketing as “zero advertising, zero tasting events—making no effort so far.”

Somehow Phelps’s everything-from-scratch, anti-commercial approach is working as a business model. Visitors are wandering in off the highway to spend a few hours sipping in the adjacent, airy tasting room, and Andalusia’s whiskeys are earning a reputation for excellence among connoisseurs and winning prestigious awards.

Phelps is hardly alone in his success. Texas whiskey is flourishing, from the Hill Country to the Gulf Coast to the banks of the Red River. Ten years ago, Texas had only two whiskey distilleries, Garrison Brothers, in Hye, and Balcones, in Waco, and both were struggling to get their young products to market. Five years ago, there was still so little Texas whiskey available that it was entirely possible—even likely—that a whiskey lover living in the state would never have tasted any. Today, sales are booming (with super-premium whiskey, the category to which most craft whiskeys belong, growing more than 300 percent over the past decade nationwide); top critics are gushing about the quality of Texas bourbons and single malts; and, amid talk for the first time about “Texas terroir,” the state is emerging as a distinct and important whiskey region.

But the industry remains in a kind of rambunctious adolescence. Visit the Texas whiskey section at a big liquor store today, and you’ll find a Wild West of products. In addition to bottles from grain-to-glass distilleries are products from respected whiskey blenders who source and mix barrels as well as cagey marketers who buy cheap, out-of-state distillate but call it Texas whiskey anyway, because someone, say, in the Metroplex registered the LLC.

Bourbon, defined

Bourbon doesn’t have to be made in Kentucky, but it must be distilled from a fermented mash of at least 51 percent corn and be stored in new, charred oak barrels.

In September 2018, twelve distilleries—including Andalusia, Balcones, and Garrison Brothers—formed a trade group, the Texas Whiskey Association, to bring order to the lawlessness. The association has sought to promote the state’s whiskey industry—largely through a new tourist route called the Texas Whiskey Trail—to foster an already growing community of obsessive fans, and to protect the category from deceptive marketing and made-up provenance. The stakes are high. “We’re right on the edge of permanently establishing Texas as having as much of an identity as Kentucky or Scotland or Ireland,” says Daniel Whittington, the cofounder of Austin’s Crowded Barrel Whiskey Co. and the host of two popular whiskey-centric YouTube channels.

But before that can happen, the industry needs to settle a question that will profoundly shape its future: What is Texas whiskey, and who gets to decide?

The marriage of Texas and whiskey seems like it should go back at least a century. Spend a day watching Phelps make whiskey on his cedar-scrub-covered ranch, and you might well figure he’s following in the footsteps of Texan forebears. Listen to Willie Nelson sing the Johnny Bush–penned “Whiskey River” or catch an old Western on TV with cowboys and gunslingers knocking back drinks in a saloon, and you might well conclude that nothing is more Texan than a glass of whiskey.

But Texas whiskey has no real history. According to whiskey historian Michael Veach, there were no licensed liquor producers of any kind in the state before Prohibition, and the first Texas whiskey distillery, Garrison Brothers, didn’t obtain its permit from the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission until December 2007. The following year, Balcones got its own distiller’s permit and, despite the later start, managed to beat Garrison to market. In September 2009, Balcones released a five-week-old corn whiskey called Baby Blue (named after the George Strait song) that debuted on shelves at two independent liquor stores in Austin. It was the first time in history that Texans could buy a bottle of locally made whiskey.

Balcones also provided the young industry’s breakout moment. In December 2012, its then head distiller, Chip Tate, submitted Balcones’s new Texas Single Malt to London’s Best in Glass competition, a blind taste test that endeavors to select the finest whiskey released in the world that year. Up against famed Scotch houses Macallan, Glenmorangie, and the Balvenie, Balcones took home first place. The win was immediately dubbed “The Judgment of London,” a modern whiskey analogue to the famous 1976 Judgment of Paris, when California wines shocked the world by besting their French rivals in a blind tasting. The victory put Balcones in the global spotlight, helped legitimize American craft distilleries (which had generally been considered inferior to their older, bigger peers in Kentucky and Tennessee), and signaled the emergence of Texas as a whiskey-producing region worth watching.

Less than six months later, in May 2013, the Texas Legislature passed a series of laws that improved the business prospects for craft distilleries. For the first time, they were allowed to open tasting rooms, offer cocktails on the premises, and sell their bottles in limited quantities directly to consumers. The new legislation transformed the industry. Before 2013, the TABC had issued 39 distiller’s permits in its history. Since the laws went into effect that September (which was declared “Texas Craft Spirits Month” by then-governor Rick Perry), the agency has approved 125 additional permits. Whiskey has played an outsized role in driving this trend, with nearly half of the 154 active distiller’s permit holders in the state having registered at least one whiskey label.

As the number of Texas distilleries has grown, it’s become clear that the state is offering something unique, a “genuine terroir story,” in the words of Chuck Cowdery, a Chicago-based writer who has been dubbed “the dean of American whiskey journalism.” Much of the flavor of brown spirits comes from barrel aging, and whiskey has historically been made in regions with relatively temperate climates, like Scotland and Kentucky, where that process can take decades. But the intense heat and huge temperature swings in Texas can cause so much expansion and contraction in wooden barrels that they can impart years’ worth of charred flavors in a matter of months. That means that, left unattended for too long, Texas whiskey can end up tasting like an ashtray. But if it’s monitored carefully, the heat can have a positive effect—it can make whiskey grow up fast, retaining some of the aggressive swagger of youth without the acrid, boozy imbalance found in many immature craft whiskeys.

“You’ve got the raw grain taste you expect in a young whiskey, but it’s really dialed back,” Cowdery says, “and you get the depth and richness that you don’t expect from four or five years of aging.”

This assessment has become widespread. In 2012, a few months before the Judgment of London, famed British whiskey critic Jim Murray honored Balcones’s scrub oak–smoked corn whiskey, Brimstone, as the top U.S. Micro Whiskey of the Year in his annual guide to the world whiskey industry, Jim Murray’s Whiskey Bible. Since then, Murray has routinely chosen Balcones and Garrison Brothers whiskeys among his favorites. Meanwhile, Ironroot Republic, in Denison, has twice won best corn whiskey at the World Whiskies Awards, and Andalusia has taken home best-in-category prizes at the past two American Distilling Institute conferences. In January, Whisky Magazine chose Jared Himstedt, Balcones’s head distiller, as Master Distiller/Blender of the Year at its Icons of Whisky America awards.

As Texas whiskey has gotten good, big players in the industry have taken note. In August, Pernod Ricard, the second-biggest producer of spirits and wines in the world, announced it was buying Fort Worth’s Firestone & Robertson, and according to insiders, the nation’s largest liquor conglomerates have shown interest in acquiring other Texas distilleries. Top consultants, like the late Dave Pickerell—the so-called Johnny Appleseed of American whiskey—and the renowned California blender Nancy Fraley, have come to the state to help new makers hone their processes. Talent is relocating here permanently too. Provision Spirits, the Blanco-based maker of Ben Milam Whiskey (spearheaded by Austin entrepreneur Marsha Milam), recently expanded by tapping Marlene Holmes, an industry veteran who spent 27 years at Jim Beam, and Heather Greene, a whiskey expert and writer, to be its master distiller and CEO/partner, respectively.

“There’s a fearlessness, an irreverence,” she said. “It feels like the frontier of new American whiskey.”

Greene, who is best known for her book Whisk(e)y Distilled: A Populist Guide to the Water of Life, moved to Austin over the summer, and when I met her for coffee, she was putting the finishing touches on Provision’s new signature Milam & Greene whiskeys. A former singer-songwriter, Greene fell in love with whiskey while living in Edinburgh, Scotland, so much so that it supplanted music as her calling. For years, she traveled the world as a brand ambassador for Scotch-maker Glenfiddich, then ended up in New York City as the whiskey sommelier at an upscale bar and restaurant called the Flatiron Room, where she also taught a series of whiskey classes. Until recently, Greene told me, she barely thought of Texas whiskey at all. When she’d worked at the Flatiron Room, “people would come in, drink it once, and not come back for the second time.”

But Texas whiskey began to excite her. The industry was new and still forming, which meant that although some of its products were misfires, there were no hidebound rules and sacrosanct customs to observe. Pick up a Kentucky whiskey, whether a $15 handle of Old Crow or an auctioned-off $2,500 bottle of 23-year-old Pappy Van Winkle, and you’re highly likely to get a bourbon with sweet corn notes, a rich texture, and an oaky char. Pick up a Scottish whiskey, whether a smoky peat-bomb from Islay or a tamer single-malt from Speyside, and you’ll taste grassy, floral elements and wisps of wood. Pick up a bottle of Texas whiskey, and you could get a Scotch-style single malt, a Kentucky-style bourbon or rye, a mellower Irish-style triple-distilled whiskey, or any number of lesser-known variations or original inventions. The upside of the lawlessness of Texas whiskey is that it is wide open for experimentation and innovation. Greene was excited to try to harness the state’s climate and put her own stamp on Texas whiskey in a way that she simply couldn’t in the more established regions.

“There’s a fearlessness, an irreverence,” she said. “It feels like the frontier of new American whiskey.”

Jim Murray is on the phone from his three-hundred-year-old cottage somewhere in the East Midlands of England. “I don’t actually give out details of where I am,” Murray tells me. Too many whiskey fans had shown up unannounced at his former home.

Murray is likely the best-known whiskey critic in the world, a global brand name, thanks to his annual Whiskey Bible, which is published in thirty countries. “Twice a week, a taxi would turn up outside my offices with a member of the public who had come in from Germany or God knows where, and then, of course, I would lose a couple hours chatting with them,” he says. “Often they couldn’t go into the offices because they’d be wearing aftershave, which would just screw my nose up, so we’d have kind of a little long-distance chat outside.”

Murray, in keeping with his whiskey idol status, has since moved twenty miles from the nearest train station, but even from this undisclosed rural location, he closely tracks what’s happening in distilleries around the world. The 2019 Whiskey Bible includes entries for Bhutan, Uruguay, and Slovakia, reams of pages on the whiskeys of Scotland and Kentucky, and expanded Texas whiskey listings.

“The thing I’ve noticed across the board in Texas is that the average seems to be higher than elsewhere,” Murray says. “And somehow having these big whiskeys kind of matches Texas. Having a spectacular Texas steak and then, later on in the night, having one of their massive bourbons, that’s quite a pleasant experience. Texas whiskey just seems to be more explosive—the flavors are much more gripping and memorable.”

Murray’s praise for Texas’s two original distilleries is effusive. “The quality of their whiskey is simply ridiculous,” he writes of Garrison Brothers. “The smaller independent distilleries from outside Kentucky are just not supposed to be this good.” In the same volume, he lauds Balcones’s Peated Texas Single Malt as “one of the greatest malt whiskeys ever produced in the USA.”

In February, Murray accepted an invitation from the East Texas Bourbon Society, a fifty-member monthly whiskey appreciation club, and traveled to the unlikely location of Longview to preside over the “first-ever Texas Bourbon Shootout.”

Inside a Holiday Inn conference room, Murray took the stage and oversaw what must have been the fussiest, most demanding, and perhaps most revelatory tasting of distilled spirits ever undertaken behind the Pine Curtain. The format Murray chose was fun and sporty, a head-to-head single-elimination blind-tasting tournament in which eleven of the state’s bourbons would compete. Everyone present had a vote. But as Murray, wearing a linen blazer and brown fedora, made clear to the audience at the outset, he was approaching the night’s proceedings with the utmost seriousness.

As the tasting began, Murray implored the crowd to follow his eighteen-step “Murray Method” (among his rules: no water, no ice, and avoid tasting in places with “distracting noises”), and for the next several hours, Murray presided over the room like a demanding college professor. He asked that the crowd of around one hundred evaluate each spirit in silence—“Listen to the whiskey,” he implored repeatedly—and, at several points, he scolded individual participants for engaging in chitchat. With the air-conditioning on full blast, Murray encouraged the tasters to warm their whiskeys in their hands, believing that doing so, as he writes in the Whiskey Bible, “excites the molecules and unravels the whisky in your glass, maximising its sweetness and complexity.” Throughout, Murray advised the participants to take it slow, to sniff and sip and ponder before rendering judgment.

In the audience that night was Jake Clements, the founder of the Texas Whiskey Festival, an annual showcase for the state’s craft distillers. “He preferred us not to swallow anything until we got down to the last two or three,” Clements recalls. (Clements believed this direction was more honored in the breach.)

In the end, scores were tallied, and the group anointed Garrison Brothers’ Balmorhea, a five-year-aged 115-proof bourbon, as the winner. Balcones’s Blue Corn Bourbon was the runner-up. Murray himself agreed with this assessment, and as he left the stage, he declared that his admiration went well beyond the top choices. “These are among the best whiskeys not just in Texas but among the world,” he said.

When Murray made the transition from London newspaper reporter to full-time whiskey critic, in 1992, the world of whiskey was a much smaller place. “There was no tourism, no whiskey magazines,” he tells me during our call. “When I wrote my first book in 1996, I went to every single distillery in the world.”

That would be impossible today. In fact, it would be difficult to visit all the distilleries in Texas alone. That’s not only because there are a lot of them, but because whiskey makers are in the midst of a passionate debate over what should qualify as a true Texas distillery.

When I visited Phelps at Andalusia, he’d made his feelings clear. He was fuming over how many new whiskey makers were taking shortcuts. Many of them, he thought, were cynically playing to Texas pride while selling a product that had little to do with the state. “They order in barrels of finished bourbon from Kentucky. They show up, dump them out, slap on their nicely printed labels that say ‘Made in Texas,’ and they call it a day,” Phelps said. “There is no one stopping this. I think that is flirting with fraud.”

The first Texas distilleries, Garrison Brothers and Balcones, may have been competitors, but they shared a similar outlook on whiskey making: they believed, strongly and vocally, in performing every step of the process in-house. Other whiskey makers who followed them took different approaches. San Antonio’s Rebecca Creek Distillery, founded in 2009, began by making vodka, and when it launched its own whiskey, in 2011, it was a light-bodied Canadian-style blend concocted from sourced Kentucky bourbon, a sourced-grain neutral spirit, and a small amount of young whiskey distilled in-house. (Its slogan, “Texas in a Glass,” still elicits eye rolls among whiskey purists.) Firestone & Robertson, which began in 2012, started by manufacturing its own sourced whiskey, TX Blended, while its head distiller, Rob Arnold, began making TX Bourbon from scratch, going so far as to use a wild Texas yeast strain in the fermentation process.

Some so-called Texas whiskeys have far murkier connections to the Lone Star State. Canadian brands concocted their own ersatz Texas whiskeys, among them Texas Crown Club and Crown Royal Texas Mesquite, and private bottlers began to sell products like Texas 1835 Bourbon, which sports a label that references the Battle of Gonzales, complete with the “Come and Take It!” slogan, but includes almost no information about the whiskey’s actual origin. (“Bottled by 1835 in Lewisville, Texas” is the only clue offered in the fine print.) Since the brand was introduced, in 2012, three different Texas-based companies have been licensed to distill or rectify it (which can just mean bottling a spirit sourced from elsewhere), and 1835’s trademark is currently owned by a Delaware-registered LLC with a mailing address in Englewood, Colorado.

As the craft whiskey market began to get more crowded, efforts sprang up to try to make it more transparent. San Antonio’s Ranger Creek Distillery, founded in 2010, started a webpage called “Makers vs. Fakers,” which educated consumers on how to differentiate “authentic, handcrafted spirits from those that are inauthentically marketed as such.” (The phrase “produced and bottled,” for instance, usually means the whiskey is sourced.) A Houston consumer advocate named Wade Woodard began filing complaints with the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau when he found whiskey labels he believed were misleading. (Woodard is now the Texas Whiskey Association’s compliance officer.) A former political operative named Spencer Whelan took a different tack. Instead of going public with complaints against bad apples, Whelan began shopping an idea to Garrison Brothers, Balcones, and a few other grain-to-glass distillers: the whiskey makers who were doing things honestly and forthrightly should band together to form a trade organization.

Sourced vs. Grain-to-glass

Grain-to-glass whiskeys will clearly state their provenance on the label. When a whiskey is sourced from another state, it gets a little trickier. Upfront distillers don’t hide when their whiskey is sourced. A good example is Treaty Oak, which makes a grain-to-glass bourbon called Ghost Hill but also makes a sourced whiskey, called Red Handed. Under the cheeky name (as in “caught red-handed”), the label clearly label clearly states that the bourbon is distilled from Kentucky and Virginia (it’s then aged and bottled in Dripping Springs). Many others are less up-front. If a bottle doesn’t include a distillation statement, it likely wasn’t made from scratch by the brand.

“My goal is to help ‘Speak the Truth’ in an industry increasingly defined by pretense and deceptive marketing practices,” Whelan wrote in an early pitch deck. “RIGHT NOW there exists a ‘once in a generation’ opportunity to form an organization that will PROMOTE & PROTECT Texas Whisky pioneers and become a RECOGNIZED LEADER in the global whisky movement.”

The initial proposal went nowhere. At the time, the industry was more rivalrous than friendly and was dominated by the big, swaggering personalities of Garrison Brothers founder Dan Garrison and Balcones founder Chip Tate, each of whom had ambitions to conquer the world with his products, not someone else’s. Tate wrote about wanting to create whiskeys that captured Texas’s “maverick tendencies, its climate, its restrictions and its freedoms, and its fierce notions of independence,” and he was lionized as a visionary in the whiskey press, which compared him to Steve Jobs and Michelangelo. Garrison was no less confident and uncompromising, wanting to “make the finest-tasting straight bourbon in the world.” Garrison was also stung that Tate had won the race to sell the first Texas whiskey.

“That broke my heart, because I wanted to be first,” Garrison tells me. “Chip knew I wanted to be first.”

When Whelan first approached them, Garrison and Tate were both focused on their distilleries and weren’t ready to make common cause. “Instead of herding cats, I’d say it was herding alpha dogs,” Whelan remembers.

Over the next several years, the industry matured and expanded. Balcones and Garrison Brothers, which had both been pushing hard just to meet demand from their distributors, reached more sustainable levels of production. (Tate departed Balcones in 2014 after a dispute with investors, and Jared Himstedt succeeded him as head distiller.) New whiskey makers like Ironroot, Andalusia, and Dripping Springs’ Treaty Oak Distilling emerged, adding fresh voices to the conversation. Eventually, Whelan’s idea of a Texas Whiskey Association finally began to take shape. Even then, prospective members had doubts.

“I was like, ‘Man, can we even get everybody together?’” remembers Himstedt, who is now serving as the TXWA’s first president. “Can we come up with a vision that is general enough that everybody can get into it, but not so general that it’s not worth doing?”

By the time the association officially launched, in September 2018, most of Himstedt’s questions had been answered. The TXWA would create its own authentication process, affixing a silver label with the words “Certified Texas Whiskey” to products that had been “mashed, fermented, distilled, barreled, and bottled in the state of Texas, with no additives other than ‘Texas-sourced water.’ ” The group would welcome any distillery as a member so long as it made at least one such whiskey. Members who also sourced whiskey from out of state, like Provision Spirits and Treaty Oak, were accepted, but their labels needed to indicate clearly what was in the bottle. A Texas Whiskey Trail would be inaugurated in spring 2019, offering whiskey enthusiasts digital “passports” that would grant them access to special events and the opportunity to earn loyalty points that could be redeemed for merchandise.

Tasting Route

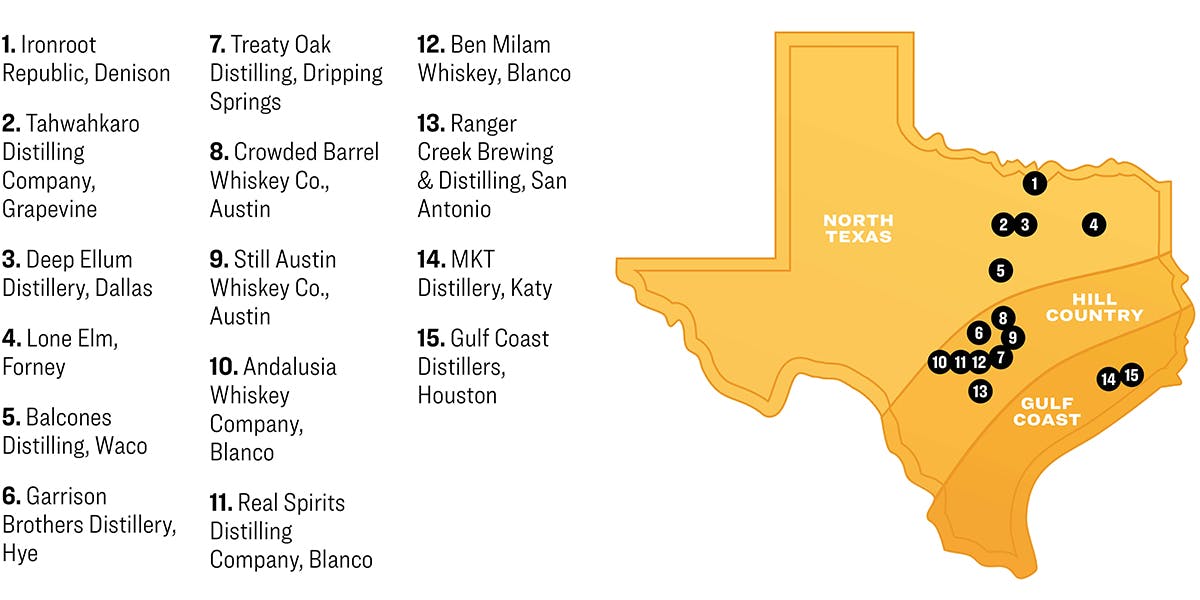

The Texas Whiskey Association’s new Texas Whiskey Trail features fifteen craft distilleries in three regions: North Texas, the Hill Country, and the Gulf Coast. The association plans on adding more stops next year

In Kentucky, Tennessee, and, recently, Missouri, state legislatures have passed laws defining what is and is not a state-made whiskey. The TXWA hasn’t yet lobbied the Legislature to take similar action, but Certified Texas Whiskey could end up as a first step toward legal codification.

Such a push would likely face opposition. When I called Mike Cameron, the cofounder of Rebecca Creek, the CEO of Devils River Whiskey, and the president of the Texas Distilled Spirits Association—an industry trade group that represents both grain-to-glass distillers and bottlers—he told me he was worried that a statewide definition would be limiting.

“Do we want to put regulations that are so tight that we can’t have success and growth?” he asked.

Cameron pointed out that the state’s spirits industry is still “evolving,” and, in fact, Texas whiskey remains a niche product. According to Nielsen sales data, there are only two Texas whiskeys among the top-one-hundred-selling bottles of whiskey—not in the world, or even the country, but in Texas—and both of them, TX Blended, from Firestone & Robertson, and Rebecca Creek Spirit Whiskey, are made primarily of spirits that have been distilled in other states. Craft spirits nationwide tripled their market share between 2012 and 2017, but they still constitute less than 5 percent of overall sales. The Texas whiskey industry may be maturing, but there’s much more room to grow.

The TXWA plans to facilitate Texas whiskey into an ever-more desirable brand, and so far the association hasn’t needed new laws to expand its membership and push its Certified Texas Whiskey standards. In early July, Travis Whitmeyer, the cofounder of Houston distillery Whitmeyer’s, told me that the TXWA’s definition had caused him “a little bit of heartburn.” Whitmeyer makes grain-to-glass whiskey with a dedicated local following (new products have been known to sell out in a matter of days) as well as sourced products that he ages and blends at his own facility. He thought these sourced products should qualify as Texas whiskey, but the TXWA did not.

“If I can’t call that Texas whiskey, then my pushback would be, ‘Okay, well, why is Texas whiskey just something that is distilled here? Why don’t you have to source all the grains from here or some percentage of the grains from here?’ ” Whitmeyer asked at the time. “We’re a hundred percent family owned and operated, and just about everybody else that I know that’s around today is either sold out already or they’ve taken on some serious heavy-hitting investors.”

But by September, Whitmeyer had come around and decided to join the TXWA. He would be phasing out the labeling on his sourced products to come into compliance. He saw the benefit of having his distillery as a stop on the trail, and he wanted to be able to influence the industry’s growth. “That’s the big thing,” Whitmeyer said, “having a voice in the group.”

About ABV

Whiskey comes out of the barrel at a range of different proofs (mostly well over 50 percent alcohol) but is then diluted with water down to a specific ABV (alcohol by volume).

It’s Friday afternoon in a shady cedar grove in the far South Austin hills, which means that Daniel Whittington, a former touring rock musician with a bald pate and extravagant beard, is getting ready to begin the weekly initiation ceremony. A group of thirty or so men and women, some of whom have traveled from other parts of the country, lounge around a few picnic tables outside a ye-olde-pub-themed tasting room called the Fang & Feather, watching Whittington—whiskey-spiked iced coffee in hand, tattered straw hat on head—as he hops onto a small wooden table and calls out to the crowd.

“There’s a lot of people today who have not been bastarded in,” Whittington says. “You don’t have an option about getting bastarded if you’re new. When I get to you, I’m going to ask, ‘What’s your name?’ You’re going to shout your name, and we’re all going to shout, your name, ‘you magnificent bastard!’ Fair enough?”

The crowd responds with a hearty bellow of affirmation, and Whittington begins.

“You over here, what’s your name, sir?” Whittington says, pointing toward a cautious-looking newbie.

“John,” the man replies.

“John, you magnificent bastard!” thirty voices bellow out in unison.

“What’s your name?” Whittington asks, finding the next raised hand.

“Doug,” comes the tentative reply.

“Doug, you magnificent bastard!”

The call-and-response keeps going as Whittington works his way around the patio in a circle. Finishing, the master of ceremonies jumps off the table.

“One of us! One of us! Gooble gobble! Gooble gobble!” chants David Thompson, a long-ago bastarded corrections officer who’s wearing a kilt and knee-high leather boots. It’s a reference to Tod Browning’s classic horror film Freaks, in which a group of circus performers bands together to enact revenge on their bosses and tormenters. Whittington flashes a grin.

If Chip Tate and Dan Garrison are the Texas whiskey industry’s swashbuckling pioneers, then Whittington is something like its clown chieftain. In 2016, he and his business partner, Rex Williams, started a YouTube channel called Whiskey Vault—an “anti-snob” guide to the world of bourbon and Scotch, in which the hosts assure their audience that the “best whiskey is the one you like to drink.” Since then, Whittington and Williams have launched another channel, Whiskey Tribe, and watched their audience grow into a benevolent cult. Whiskey Vault and Whiskey Tribe each have more than 100,000 subscribers and are the first and third most popular whiskey-centric channels on YouTube, respectively. As their following grew, Whittington and Williams, who both help run a quirky nonprofit business school called the Wizard Academy, wondered whether they could harness fan enthusiasm into whiskey production. Last year, with the help of an online fundraising platform called Patreon, they opened the Fang & Feather, as well as Crowded Barrel, “the world’s first crowd-sourced whiskey distillery,” on the Wizard Academy campus.

The Whiskey Tribe that gathers at the Fang & Feather on Friday afternoons is devoted to what Whittington and Williams have created. As I talk with Thompson, the kilt-wearing corrections officer, and a few of his friends, they show off their medieval-looking Whiskey Tribe challenge coins, refer to Facebook as “the Whiskey Tribe app,” and describe what amounts to the group’s secret handshake—ask Whiskey Tribe members anywhere in the world “How do you whiskey?” and they will reply, “With magnificence!” (They also take periodic dry weeks together.) The Whiskey Tribe is a fully formed world on its own, but for the most curious and committed members, it’s also a gateway into a new kind of whiskey-obsessed lifestyle.

A few weeks after visiting the Fang & Feather, I meet another Whiskey Tribe member, José Martinez, a 26-year-old exercise-machine repairman with a twirly circus strongman mustache. Originally from the Rio Grande Valley city of Alamo, Martinez had moved to San Antonio for college and then to Austin, slowly growing more curious about whiskey, largely self-educating through YouTube channels like Whiskey Vault and It’s Bourbon Night. In 2018, Martinez was getting ready to book a trip to the Kentucky Bourbon Trail when he heard Whelan pitch the idea of the Texas Whiskey Trail. He canceled his plans. “I said, ‘Why go to Kentucky when we have so much here?’ ” Martinez tells me.

Martinez is now the Texas Whiskey Trail’s top-rated “trailblazer,” which means he’s likely spent more time at the TXWA’s member distilleries in 2019 than anyone in the state. His entire nonwork calendar revolves around Texas whiskey. Tuesdays are Texas Tuesday Happy Hours at the Austin whiskey bar Seven Grand. Fridays are the Fang & Feather conclaves. Then, “literally every weekend is a different whiskey event,” Martinez tells me. “If there isn’t an event, then I’m going to a new distillery.”

Martinez’s September plans included Andalusia’s third anniversary party (Phelps signed his bottle of cask-strength Stryker), Balcones’s inaugural BourbonFest, and a trip to Hye for Garrison’s annual Cowboy Bourbon release. “It sells out in two hours, so I’m going to try to get there four to six hours before the gates open at eleven,” Martinez says. This wouldn’t be his first time camping out for new whiskey. When Katy’s MKT Distillery released its limited-edition corn whiskey in August, Martinez had left Austin well before dawn.

This zeal is not lost on Texas distillers. They’ve turned their special releases into can’t-miss events to cater to the surging community of whiskey devotees. But there has been growing camaraderie within the distilling community too. When I visit Himstedt at his office at Balcones’s 65,000-square-foot headquarters, in a historic fireproof storage building in downtown Waco, he says he remembers clearly the era when “everybody thought they had to be at each other’s throats.” Himstedt had helped start Balcones with Tate, and he’d been there as they’d raced Garrison to release the first-ever Texas whiskey.

The zeal is not lost on Texas distillers. They’ve turned their special releases into can’t-miss events.

But the old battle lines were fading away, and Himstedt—a laid-back Baylor ceramics and social-work major who grew up largely in Brazil with Baptist missionary parents—seems more than happy to help to bring about this new order. As we sit down to talk, Himstedt brings me a cup of coffee in a handmade clay mug. Knowing his background, I ask if he’d made it. He shakes his head. The mug had been made by one of his teachers.

“In ceramics they call it surrounding yourself with mirrors. You try not to spend too much time with your own work,” Himstedt says. “I guess it’s the same with whiskey too. You do your work and then spend time with others so you can put yours in context.”

Earlier this year, Himstedt, Garrison, Phelps, and many of the other Texas whiskey distillers had gathered at the Star Hill Ranch in Northwest Austin on the evening before the second Texas Whiskey Festival. The TXWA had just inducted Provision Spirits and Grapevine’s Tahwahkaro as member distilleries, and Crowded Barrel was set to release the first-ever collaborative blend of different grain-to-glass Texas whiskeys—a rich and delicious combination of Ironroot bourbons, Andalusia’s Stryker, and Balcones’s Mirador Texas Single Malt. That night, over barbecue, cigars, and whiskey, Himstedt watched everyone coming together. Heather Greene had flown in from New York and was meeting many of her future Texas whiskey colleagues for the first time ahead of her move to Austin. Newer distillers like Forney’s Five Points Distilling had made the trip, introducing themselves and offering up tastes of their Lone Elm wheat whiskey. A decade into Texas’s whiskey experiment, Himstedt could see that an industry and community had blossomed.

“It felt like, ‘We’re going to have decades of exciting hard work, but it’s going to be worth it,’ ” Himstedt says. “We don’t even have to knock it out of the park; we just need to be remotely responsible and diligent with this thing that has its own life and energy.”

This article originally appeared in the November issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Wild West of Whiskey.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Libations