The Alamo, where one of the world’s most famous last stands took place—a sacred Texas shrine abutting Ripley’s Believe It or Not! Odditorium—has always been as much a puzzle palace as a historic site. Only a few weeks after the 1836 battle ended and the funeral pyres of the defenders had stopped smoldering, the sprawling Spanish mission that had been turned into a fortress was being torn down by the victorious Mexican Army. And that was just the beginning. With its walls and houses destroyed or repurposed, its boundaries engulfed by urban expansion, its dignity degraded by amusement arcades and souvenir shops, and its physical integrity threatened by the ceaseless exhaust of automobile traffic, the Alamo has been transformed over time into an almost incomprehensible jumble of history, commercialism, and pilgrim worship.

Somehow, though, it never lost its magic. Even today, surrounded by the high-rise hotels and office towers of downtown San Antonio, it’s a haunted place. At least it has been that for me and for many others who developed, at an early age, a love for its otherworldly presence and its complex history.

I was seven when I first saw the Alamo in person and was seized by the understanding that it was a real place and not just the setting for the gruesome final scene of Walt Disney’s 1955 series Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier. Twenty-three years ago, I published a nearly six-hundred-page novel called The Gates of the Alamo, which was excerpted as a cover story for Texas Monthly. I spent eight years researching and writing it, reading old letters and documents, pressing historians on abstruse points of historical detail. But none of that was enough to get the place out of my system. Year after year, I keep returning to the Alamo, staring at it, trying to conjure through more research or more focused imagination what this fortified mission on the Mexican frontier would have looked like before it passed through the prism of myth.

In 2015 the Texas General Land Office assumed responsibility for the Alamo after a more or less hostile takeover from its long-term custodians, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, and formed an alliance with the city of San Antonio to, well, make my dreams come true. Its goal was to preserve and restore the Alamo after decades of neglect, plus to “reimagine” it, a term that later became deeply contentious, as the project ignited battles over history, identity, and politics. It looked for a while like the whole enterprise was dead, until it emerged again with different design elements, different faces, and a lower-key description—the Alamo Plan. But “reimagine” is still the right word for a long-needed effort to present the Alamo anew as its old self—to transform it into a genuine historical site and not just an inscrutable building in the heart of San Antonio. The physical changes that have been taking place so far on the grounds have been accompanied by an intellectual redevelopment—an argument about what the Alamo is, what it represents, and whose stories it should tell.

“It’s a big project,” Kate Rogers, the executive director of the Alamo Trust, the nonprofit managing the overhaul, told me as we walked through Alamo Plaza in April. “It’s a heavy lift. But at the same time, it’s also the Alamo, and people care deeply about it.”

That’s always been the problem. People care deeply about the Alamo, maybe too deeply. The Alamo doesn’t just represent a moment in history; it has a way of hijacking the whole idea of history itself.

A Forlorn Ruin and the “Ridiculous Scroll”

One of the first images of what the Alamo looked like after it had been overrun and captured by the Mexican Army in 1836 is a watercolor sketch made by twenty-year-old Mary Maverick. She arrived in Texas in 1838, with her husband, Sam; the first of their eventual ten children; and the ten enslaved servants they had brought from South Carolina. One day during that first year in which she was adjusting to and exploring her new home, she set up with her brushes near the east bank of the San Antonio River, at what had been the southwest corner of the old mission—roughly where the Odditorium resides today.

The centerpiece of her amateurish rendering is the shattered, roofless remains of the church of Mission San Antonio de Valero—the building that the world somewhat mistakenly recognizes today as the Alamo. Next to the church, she sketched in part of the extensive structure—now known as the Long Barrack—that in its former days had housed a two-story convent as well as a granary, textile workshop, blacksmith shop, and other enterprises of mission life.

By the time Maverick made her sketch, much of the rest of the Alamo—a four-acre complex of dormitories, offices, storage rooms, kitchens, infirmaries, chapels, corrals—was gone. “They are now as busy as bees tearing down the walls, etc.,” one witness—an American doctor named Joseph Barnard—reported in May 1836, two and a half months after the Alamo fell to General Antonio López de Santa Anna’s troops. But by that time, Santa Anna had been defeated at the battle of San Jacinto, and only two days after Barnard made his observation, the Mexican forces that had been left behind to guard San Antonio and destroy the Alamo marched out of town.

In the years to come, San Antonio would spread across the river that had once been its eastern boundary, its downtown expanding against the vanished walls of the Alamo and the plaza in front of the ruined church. After Texas joined the union, in 1845, the U.S. Army repaired the church, turned it into a storehouse, and added an arched gable on top. A critic referred to the new design feature as “a ridiculous scroll, giving the building the appearance of the headboard of a bedstead.”

But that headboard was the architectural flourish that helped turn this

battle-damaged, stunted church into a worldwide visual icon. Even today, even with the distinctive gable that has crowned it for more than 170 years, the Alamo church still appears as forlorn and mysterious as it did in Mary Maverick’s sketch.

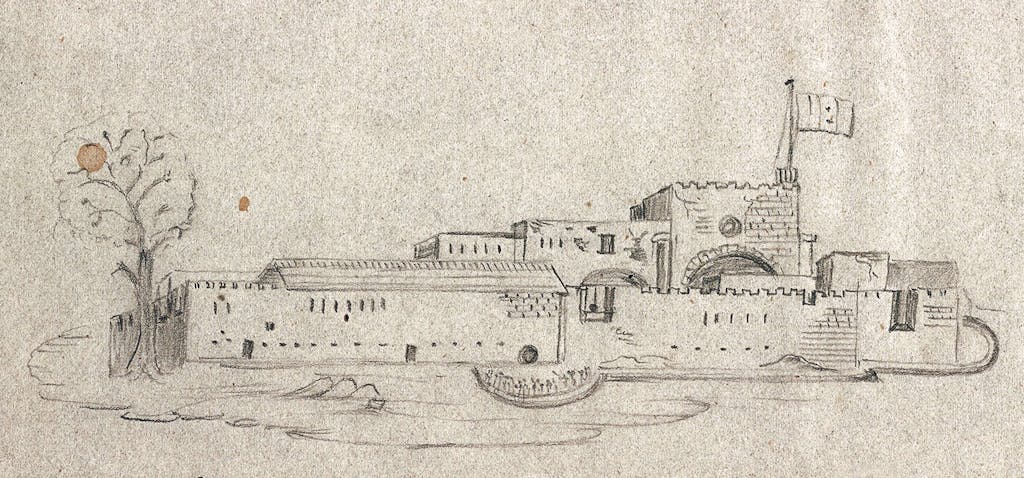

Most of the visitors who stand in front of the church think they’re looking at the Alamo, but they’re not. To understand why they’re mistaken, take a look at another sketch (on the opposite page), this one made by an officer in the Mexican Army, José Juan Sánchez-Navarro, who participated in the 1836 siege. It’s not an immaculately credible image—Sánchez-Navarro apparently made a quick on-the-scene sketch that several years later he enhanced from memory into a finished illustration—but it’s widely considered to be the only existing image of the Alamo as a fortress as it might have looked to someone viewing it from the outside. The artist was situated, according to a note at the bottom of the drawing, on “the roof of the Veramendi house,” which at that time was a prominent residence on Soledad Street, about a quarter mile west of the Alamo.

What you see when you look at the sketch is nothing like the Alamo today. It strongly resembles a medieval castle, “an enormous battlement,” as one Mexican officer described it in 1828, with parapets and deep gunports and a huge central building rearing up above its crenellated walls. It’s hard to discern exactly what this building is supposed to represent. Is it the Alamo church? If so, it’s almost freakishly taller than the church that exists today. Or could this looming edifice be part of the complex of mission offices and priest quarters at the southern end of the Long Barrack, in which case the church might be the off-to-the-side structure to its south? The drawing, as I said, isn’t perfect, but I think it’s accurate in the sense that it makes the case that the Alamo church—the building that we think of as the Alamo—would not have appeared to an officer in Santa Anna’s army as the major objective within the fortress he would soon be ordered to attack.

What Is “the Alamo”?

The Alamo casts such a powerful physical spell—a mournful Spanish colonial monument in the heart of a busy city—that I never really gave much thought to its awkward self-presentation until, back in the eighties, a documentary filmmaker from Chicago named Gary Foreman began promoting a startling redefinition of Alamo Plaza. His plan would have stolen much of the focus from the Alamo church and reestablished the expansive contours of Mission Valero, requiring the razing of three late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-

century buildings that now sit atop the boundary of the west wall of the mission, the place where Alamo commander William Barret Travis is thought to have had his headquarters and written his famous “Victory or Death” letter.

Foreman’s plan was never realized, but it helped bring a renewed public awareness to the tawdriness that had been allowed to despoil Texas’s most sacred real estate, and as a thought experiment it opened people’s minds to how the Alamo might look if it could be understood as something more than a puzzling single building.

In 2016 I moderated a panel for the Texas Tribune Festival that featured state senator José Menéndez, land commissioner George P. Bush, and Phil Collins, the British rock star who had become the unlikely possessor of the world’s greatest collection of Alamo artifacts and documents. Collins’s gift of that collection to the State of Texas had helped stir interest in a bill that Menéndez introduced to create a preservation fund and advisory committee whose purpose was to turn the Alamo, at last, into “a world-class site.” It seemed, during the course of that conversation, that something along the lines of Foreman’s Alamo dreamscape—much different from it, but equal to it in ambition—was a near-future inevitability. The state had pitched in an initial $31.5 million, big names from business and philanthropy had been brought on board to help raise the many more millions that would ultimately be needed, and a prestigious historical design firm had been hired to bring coherence and proper reverence to a space that had long been visibly short of both.

But all that was before the project’s rendezvous with reality. When the first conceptual sketches of the proposed master plan were unveiled in 2017, the public reaction ended up being “Uh . . . no.” The plan generally adhered to the agreed-upon goals: somehow restore or define the footprint of the mission and turn the trio of buildings on the western edge of Alamo Plaza into a museum. The problem was the transparent glass walls that the designer had proposed as a way to suggest where the walls of the original Alamo had once stood. They gave the impression, at least in those initial renderings, of turning a site that had been a vibrant and open civic space in San Antonio for 170 years or so into something exquisite but untouchable. Jerry Patterson, the former land commissioner who, during his tenure, had acquired the Collins collection for the state, dryly summed up the problem: “The Alamo,” he observed, “is not art.”

Another version, put forth the next year by different designers, dispensed with the glass walls idea but subtly enclosed Alamo Plaza with a combination of railings, gates, and landscaping barriers that still gave off an access-denied vibe to San Antonians.

But those weren’t the only teeth in the buzz saw that confronted the Alamo reimagineers. Revisionists complained that the new plan would end up recycling in a better and more comprehensible package the same old one-sided narrative of Anglo triumphalism that had been the poison pill of Texas history. Traditionalists objected that an interpretive agenda that focused on the Alamo’s three-hundred-year history and not just on its few weeks as a battlefield in 1836 would blur the very event for which it was

remembered and revered. The discovery in 2019 of three sets of human remains by archaeologists in the deteriorating Alamo church led to lawsuits by the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation, descendants of some of the Indigenous people who had provided the labor to build the mission and keep it alive as a Spanish religious outpost. For the Tap Pilam, the Alamo’s status as the “cradle of Texas liberty” was a distant second to its importance as a cemetery where, the descendants claimed, more than a thousand native residents were buried. One of the bodies found in the church appeared to have been interred in a coffin, suggesting it might have been an Alamo defender, which led to another lawsuit, demanding a DNA test, by the Alamo Defenders Descendants Association. (Both lawsuits ended in settlements.) And then there was the Woolworth Building, one of the three edifices on the plaza’s western edge. Because it had been the site of a sit-in in 1960 that helped lead to the desegregation of lunch counters, shouldn’t it be preserved for its own historical contribution and not subsumed into a massive Alamo museum?

A Cenotaph’s Weight

Of all the obstacles the planners faced, the most unbudgeable—literally—was the Alamo Cenotaph, which has resided in the middle of Alamo Plaza since 1939. It is a sixty-foot-high shaft of marble decorated with friezes by sculptor Pompeo Coppini. It depicts the Alamo defenders and an allegorical figure, the Spirit of Sacrifice, rising from the flames. But the Cenotaph does not mark the resting place of the Alamo dead. The bodies were burned outside the fort, and no one knows with any certainty what became of their remains beyond some representative ashes and bits of charred bone that were later interred into a pair of coffins by Tejano leader Juan Seguín.

The Alamo renovation plans, from Gary Foreman’s onward, had called for the Cenotaph to be moved out of the plaza and reassembled south of where the main gate of the mission had once stood. The latest proposal sparked a pride-of-place war, especially for the very vocal critics—many of them descendants of the Texas rebels who had defended the Alamo—who did not believe that a monument in front of the Menger Hotel would carry the same emotional charge as one that stood within the plaza. As positions hardened, the previously not-much-noticed Cenotaph—the edifice that had so unimpressed heavy metal star Ozzy Osbourne in 1982 that he peed on it in broad daylight—became the emblem of all that must be upheld and all that must be defied.

The controversy touched the exposed nerves of America’s season of cultural reckoning. When graffiti appeared on the base of the monument denouncing the Alamo’s role in white supremacy, members of a group called the Texas Freedom Force appointed themselves to stand guard with their assault rifles against any further defacement or any further insinuation that the Alamo had anything to do with racism or slavery.

The Cenotaph, along with the redevelopment of the Alamo and the reinterpretation of history it portended, morphed into a proxy Republican political battle. Rick Range, one of the three primary opponents who tried to unseat George P. Bush as head of the state’s General Land Office in 2018, accused Bush of turning the Alamo into “a politically correct theme park.”

As the temperature climbed, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick bigfooted his way into a ten-hour meeting of the Texas Historical Commission in 2020 and asked, “Do you think Davy Crockett in 1836, when he was behind that barricade with his men, would have said, ‘You know, one day they’re going to build a monument to us, and you know where they’re going to put the monument to us? They’re going to put it over there, in enemy territory!’? ”

The members of the commission responded to Patrick’s line in the sand by voting 12–2 not to relocate. It seemed, for a while, as if the whole five-year enterprise to reenvision the Alamo was now an empty tomb of its own. But the decision to keep the Cenotaph in place eventually served to defuse the most incendiary issue and gave the state, the city, and the Alamo Trust—which now oversees the day-to-day operations of the site—a clearer path to proceed with their plans.

The “Authentic Way”

When I was in San Antonio this past April, I was reminded of just how crucial that restart was. Standing with my back to the church, I faced the buildings where the west wall had once been, and swept my gaze toward the other downtown buildings just south of them that occupied the general area where an army column had maneuvered during the final assault of March 6, 1836, to fight its way into the Alamo compound. But the assault now was from garish signage for the Guinness World Records Museum, the Plaza Wax Museum, Ripley’s Believe It or Not! Odditorium, Ripley’s Haunted Adventure, and Tomb Raider 3D. There were window and lobby displays of a roaring T. rex, a purple Transformer-like robot, giant heads of Donald Trump and Joe Biden, full-size effigies of Daniel Craig as James Bond and Game of Thrones actor Peter Dinklage, and—next to the place where Mary Maverick had made her sketch—a puzzling life-size figure of a waiter wearing a bow tie and holding up a tray of doughnuts.

“Restore reverence” is the first agenda item of the Alamo Plan, and if I hadn’t already known that the state had negotiated with most of these businesses to end their leases so they could be moved to less hallowed downtown real estate, I might have wondered if that was an impossible goal. As it was, it seemed remarkable that these arcades had been allowed to stand for so long on the very foundation of the Alamo, presenting a demoralizing and drecky counterweight to the enigmatic majesty of the church.

One big improvement was already visible. Wandering through Alamo Plaza, I no longer had to worry that I was going to be hit by a car. A block-long stretch of Alamo Street, the thoroughfare that had routed traffic and tour buses since time immemorial right through the middle of Alamo Plaza, finally and officially had been closed to vehicular traffic the year before. Blocking the street and making the grounds of the mission fully walkable had long seemed to me the obvious first step in any serious Alamo plan.

There were other signs of awakening reverence and coherence. Next to the window where the figure with the doughnuts stood, there was a new display: an artillery ramp and a replica of the eighteen-pound cannon that Travis shot off in defiance when Santa Anna ordered the surrender of the garrison. A statue of José Toribio Losoya, a Tejano who had grown up in the Alamo compound and had lost his life defending it, had recently been moved to the foot of the ramp, near the place where his family’s workshop had once stood.

“We’re trying to separate what we do here from politics,” Kate Rogers told me when she met me on the plaza. Before she was executive director of the Alamo Trust, she held a leadership role at the Charles Butt Foundation, where, according to the business-speak in her official bio, she had “facilitated community collaboration and alignment to drive systemic change.” I took that to mean she considered herself a diplomat, and that’s how she came across.

“The temperature has been lowered,” Rogers told me. “Some of the elements that were most controversial to the plan have been removed. We’re not tearing buildings down, we’re not putting up glass walls, we’re not kicking the parades off the grounds. I think this is a really good time to be doing this project because we have a chance to tell the story in the right way, in an authentic way.”

She was there with Ernesto Rodriguez, the Alamo’s senior curator and historian and a San Antonio native who’s been studying the Alamo from the ground up for more than twenty years.

“This is not just my history or your history,” he said with a detectable note of zeal, as we stood in front of a Davy Crockett statue that was a new addition to the plaza. “It’s everyone’s history. It’s a world event.”

There was also a statue of Susanna Dickinson, the wife of defender Almaron Dickinson and the celebrated Anglo survivor of the conventional Alamo story. (The twenty or so Tejano women and children who survived the battle had been background presences at best in the popular versions of the battle’s history.) Several other statues were on the way, Rogers said, including likenesses of Hendrick Arnold, the Black scout who served in the Battle of Bexar and at San Jacinto, and of Emily West Morgan, the free Black woman, originally from Connecticut, who accidentally entered history when she became a prisoner of Santa Anna and, supposedly (but probably not), became the inspiration for “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” And there was already a statue of Juan Seguín in the Alamo’s old cavalry courtyard.

Neither Rogers nor Rodriguez said so directly, but it was clear enough that these bronze figures were a way that the new Alamo Plan meant to subtly redress the Anglocentric narrative of the Texas Revolution.

Shrine Within a Shrine

After pointing out where mortar had been injected to stabilize the flaking limestone of the Long Barrack, Rogers noted another new feature: a replica of the wooden palisade that at the time of the siege spanned a gap in the mission walls and that some historians believe was the final battle station of Crockett and his Tennessee volunteers.

Then we walked around the church and past the Alamo’s gift shop, which was built in 1937, originally as a museum. (By the way, contra Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, there is a basement in the Alamo. It’s under the gift shop.)

Beyond the gift shop and behind the church was the extensive garden that the Works Progress Administration had created in the thirties, an aesthetic enhancement that had the effect of sowing even more confusion about the actual layout of the Alamo, since it left the impression that the Alamo had been essentially one building—the church—with a big backyard. In that backyard, construction was well underway on the Alamo Collections Center that is set to open this month. It’s a 24,000-square-foot showcase for the Collins collection and other items—including the impressive Spanish colonial artifacts amassed by the Donald and Louise Yena family—that are now among the Alamo’s holdings.

We stopped in at the building to the south of the church that had once been the excellent research library maintained by the Daughters of the Republic of Texas and is now another temporary museum. Rogers and Rodriguez ushered me into a storeroom off the main exhibit space that was crowded with artifacts and oddments. There, for instance, were the doors of the same Veramendi house on whose rooftop José Juan Sánchez-Navarro had stood to draw his sketch of the Alamo. Against the far wall of the room was a desk once used by Sam Houston. A few feet away sat a piano that had belonged to Clara Driscoll, the philanthropist from a South Texas ranching family who, in 1905, saved the Long Barrack from destruction by fronting its purchase for the State of Texas with her own money. (She later decided the building should be destroyed after all so that it wouldn’t distract from the iconic and moody presence of the church, a bit of early reimagining that ended in a bitter dispute with a Daughters of the Republic of Texas faction led by Adina de Zavala, who saved the Long Barrack all over again by barricading herself inside it for three days in 1908.)

Above Driscoll’s piano was the original painting from which the poster for the sixties film The Alamo was made. It was a movie whose release was such an epochal event in my Texas childhood that school was suspended so we could go downtown to see it. The poster featured a painting whose central focus was John Wayne as Davy Crockett facing off against the entire Mexican Army. The painting had been a subject of ridicule—it earned a Bum Steer award in this magazine in 1975—after the Daughters first displayed it in the Alamo gift shop, a prime example of the cheesiness that has long been part of the Alamo visitor’s experience. But by now, it had been more than sixty years since the movie came out, and the painting was a venerated historical artifact of its own.

“That’s a pilgrimage painting,” Rodriguez said. “There’s a group of people who will come here every year, and they always ask about it, because they grew up with the John Wayne movie. We tell them it’s in our vault, and they’re just happy it’s cared for.”

Much of the Collins collection is also in the vault, at least until the Collections Center opens, but Rodriguez brought out a few archival file folders so I could have a look at some of the documents that Collins had acquired and that would soon go on display.

It was my second sneak preview. In 2011 American History magazine sent me to Switzerland to write about the curious case of Collins and his Alamo mania. An imaginative little boy in a London suburb, Collins happened across the same 1955 Walt Disney Davy Crockett series that had so enthralled me when it was playing one day on my family’s black-and-white TV. The Davy Crockett frenzy never quite caught on in the UK, so Collins ended up as the loneliest Alamo fanatic in England, with a faux coonskin cap that his grandmother fashioned out of a cut-up old fur coat.

Collins met me at the airport. We drove to his house outside Geneva and watched The Alamo in his living room. (Seeing John Wayne’s version of the story was what had cemented his Alamo obsession.) After our viewing of the movie—an unabashed geekfest in which we called out the upcoming dialogue to each other—we spent the better part of two days in his basement, as he showed me the collection that, in a few years, he would end up donating to the State of Texas. In 2021 Texas Monthly devoted a cover story to the suspect authenticity of some of the items in the collection, but Collins never gave me the impression he was trying to pass something off for what it was not. He was a humble docent of his own museum who seemed to be satisfied with a “who knows” attitude about some of the more contentious artifacts.

He handed me a bowie knife that he admitted “has lived a life of controversy.” I could certainly understand, as I hefted it in my hand, why anyone would want to believe that this finely balanced killing instrument had been the very knife that Jim Bowie had used at the Alamo. “It’s things like this,” Collins said, “that I know people will say, ‘Prove it.’ ”

Proving it, Rogers told me in April, is what the Alamo plans to do with any item from the Collins collection (or anywhere else) that it puts on display. She said they were working on a complete inventory and assessment from a host of third-party appraisal experts.

Even though some of Collins’s more charismatic artifacts, such as the bowie knife, have been called into question, I haven’t yet encountered anyone who has serious concerns about the documents. And it’s the documents that give you the real history buzz.

“These tell the story,” Rodriguez said, opening the file folders and carefully withdrawing a few of the paper items that make up the heart of the Collins collection.

I had seen them all before in Collins’s basement, but encountering them again in the locale where they were written gave them an extra charge of time-warping reality. Here, for instance, was something hurriedly scrawled on the afternoon of February 23, 1836, as the Texian rebels headquartered in San Antonio were taken by surprise by the sudden appearance of the Mexican Army. As they rushed to the safety of the Alamo, they brought along thirty head of cattle owned by a prominent Tejano citizen of San Antonio named Ignacio Pérez. The piece of paper Rodriguez displayed was a receipt for those cattle, signed in the heat of a frantic retrenchment by William Travis. Another document: the chilling general orders from Santa Anna, distributed to his commanding officers on the afternoon of March 5, 1836, informing them of what would occur the next day. “The time has come,” the command said, “to strike a decisive blow upon the enemy occupying the Fortress of the Alamo.”

That ominous announcement was still echoing in my imagination as we walked back across the plaza to the Alamo Trust offices in one of the three buildings slated to be part of the one-hundred-thousand-square-foot visitor center and museum that would be the final piece of the Alamo makeover. If everything falls into place, on March 6, 2026—the target date for the museum’s opening—a visitor will be able to stroll three floors of exhibition galleries tracking the Alamo from the Indigenous era to the Spanish mission period, the Mexican Republic, and the 1836 battle, all the way through later controversies such as the Clara Driscoll/Adina de Zavala conflict and the dispute over the authenticity of Collins’s bowie knife. There will be cafes, a rooftop event space, and an immersive 4D theater. That ultimate phase of the Alamo Plan is not a sure thing. It depends on whether the Legislature approves the $379 million budget request, if additional private funds can be raised, and whether further controversies over history and identity can be kept at a low simmer.

The flare-up over the Alamo’s redesign seemed to have subsided after the issue of moving or not moving the Cenotaph was settled and tempers cooled a bit. But it was only the latest skirmish in an inexhaustible war over identity and representation.

If you knew what to listen for, you could find elements of that struggle everywhere. The audio tour I rented from a kiosk in Alamo Plaza tells the story of “bravehearted men and women” who “came to Texas in search of land and other economic opportunities.” A short film that was playing to a scant audience in an open-air patio proclaimed that “the Alamo stands as a testament to the cause of liberty.”

Get-acquainted media like those were part of what the Alamo Plan was

working to bring up to code. Liberty has a different meaning when you consider that the “land and other economic opportunities” sought after by the Anglo colonists who came to Mexico in the 1820s and 1830s very much depended upon the establishment of a cotton economy built on enslaved labor. Slavery was far from the only spark that ignited the Texas Revolution—multiple Mexican states that had outlawed slavery also rose up against the dictatorship of Santa Anna—but in terms of its ultimate effects on the course of Texas, U.S., and Mexican history, it was the most toxic and consequential. In fact, the Alamo story, as Rodriguez had just reminded me, is very much a “slave narrative.” That’s because Joe (last name unknown), the young man who was enslaved to William Travis and the only combatant that we know of who survived the battle, was also the eyewitness who provided many of the details of the final assault and thus helped set the template for the Alamo’s story of heroic defiance. (“Come on, boys,” Joe recalled Travis saying as he clambered up to the wall, “the Mexicans are upon us, and we will give them Hell.”)

The Impossible Task

By the time I returned to the Alamo in December, Rogers had kindly emailed me the updated talking points that docents were to use in orienting visitors. The new commentary was a step up, broader and more complex than the blunt “we won” narrative I had heard from Alamo guides in the past. It began at the beginning, with the founding of Mission San Antonio de Valero by Franciscan priests in 1718 and its construction by Indigenous people who had to make a hard choice between tolerating Spanish encroachment or remaining the target of Apache and Comanche raids. From there it comprehensively presented the next three hundred years of the mission’s history, including of course the battle, and not leaving out either slavery or Ozzy Osbourne.

The talking points were far from the only thing that had changed in the past eight months. Just south of the big Christmas tree in the plaza, work was underway to construct a depiction of the gatehouse and defensive works that had guarded the main entrance to the Alamo when it was a fortress. Tomb Raider 3D and Ripley’s Haunted Adventure no longer sullied the venerable precincts of the old mission wall. The statues of Hendrick Arnold and Emily West Morgan, the Black icons of the Texas Revolution, now stood in the same courtyard as those of slaveholding Alamo heroes Jim Bowie and William Travis.

But the biggest difference was the new Collections Center, only three months away from opening to the public. It had been erected at the eastern perimeter of the garden area, where the Alamo restrooms had once been. It was a modern limestone structure that looked like a college classroom building and had not escaped criticism when its preliminary renderings were revealed. (“Too big to be that plain in that location,” one architect complained.)

But it had been deliberately designed, Rogers told me, to look relatively sleek and modern so that it wouldn’t add to the confusion, as the gift shop and other ersatz Spanish colonial buildings on the grounds had, of what was the original Alamo and what was not.

Inside, the building was expansive and airy, with a main lobby large enough to accommodate a 22-foot-high landscape mural and wall space where more than one hundred artifacts from the Collins and Yena collections would be displayed. At the moment, the walls were bare, and the exhibition spaces, conservation labs, storage vaults, and temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms for storing precious documents all still smelled of fresh paint. Thin plastic sheeting lined the corridors where future Alamo visitors would parade from one exhibit room to the next.

In one of these rooms, a magnificent Alamo diorama that Collins had donated was already in place. The diorama was the work of artist and historian Mark Lemon, and it depicted the mission as it might have appeared during the 1836 siege. It was huge—14 feet by 9 feet—beguilingly detailed, and almost eerily real. After studying it for a while, I stationed myself on its western edge and crouched down until I had something like the view José Juan Sánchez-Navarro had when he sketched the Alamo from the roof of the Veramendi house. I could see how he had gotten the impression of a formidable fortress, so completely unlike the physical Alamo—that single building overwhelmed by downtown San Antonio—that I and everyone else in Texas had grown up misperceiving.

Staring at this sprawling model, I began to understand what had drawn me to the Alamo as a young boy and had continued to hypnotize me over the course of my whole life. It was not the battle itself, nor what it represented of the heroic or grasping currents of the human story. It was something deeper—the mystery of a vanished age. The Alamo, with its layers upon layers of history and corrupting change, had always been an imperfect window through which to view the past, but it was my window, my portal, the first thing I encountered that made me really understand that the time I lived in was not the only time there ever was.

After I left the new Collections Center, I walked over to the Alamo Cenotaph, once the untroubled symbol of an old-style, bravehearted valor and now the embattled embodiment of something much more complex—the tension between a historical narrative that was itself stuck in the historical past and one that was attempting to adapt to an increasingly unstable present.

The Cenotaph wasn’t looking so great. Time had not been kind to the marble reliefs of the Alamo defenders. Jim Bowie’s nose looked like it was about to fall off, and you could see gaps where the marble blocks were settling beneath the soaring image of the Spirit of Sacrifice. Even though the Cenotaph would remain in place, it was scheduled to be taken apart and refurbished.

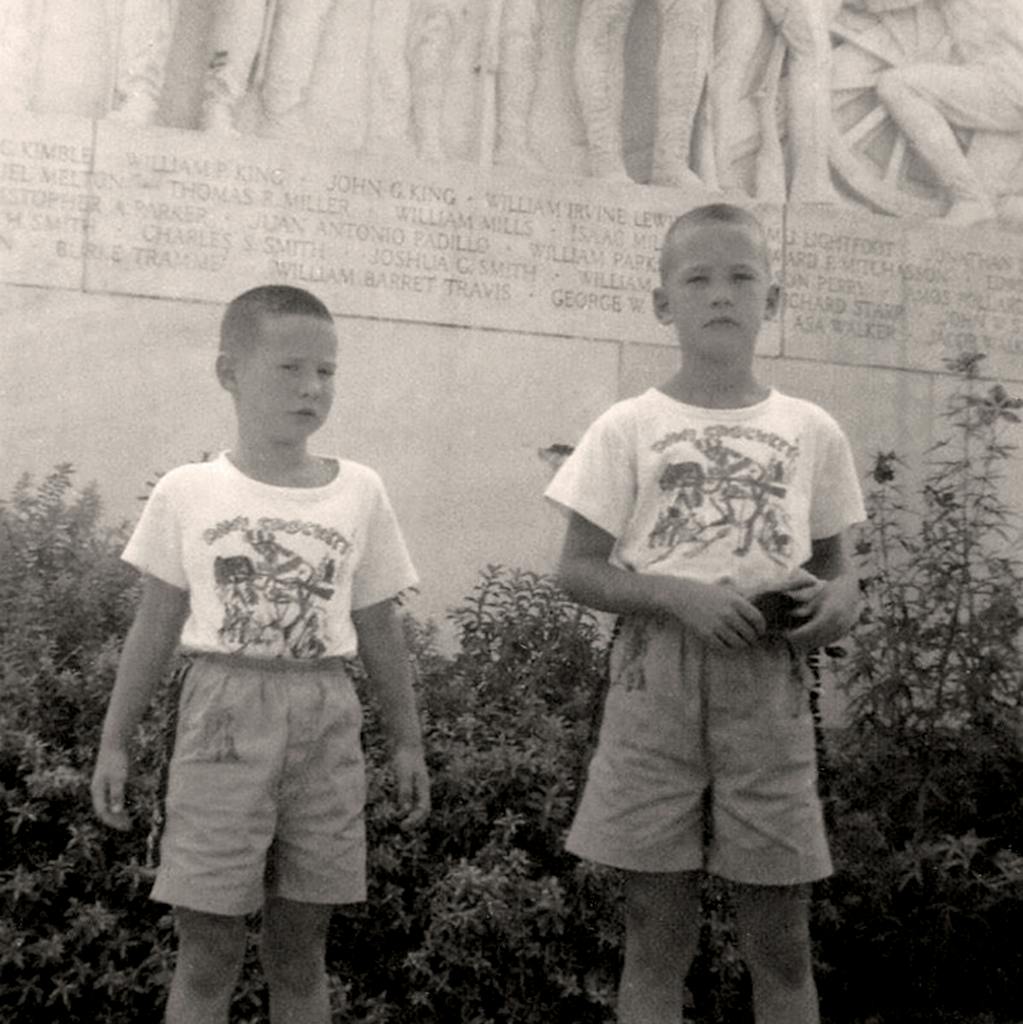

There’s a photo of my older brother, Jim, and me that my mother took in front of the Cenotaph in 1956, on our first visit to the Alamo. We were wearing our matching Davy Crockett T-shirts and Davy Crockett short pants. It amazes me to think that this coruscating old monument was, at that point, less than twenty years old. My brother and I, and Phil Collins in his ersatz coonskin cap across the Atlantic, were at that time inheritors of a stirring but narrow story. But times change, children grow up, and stories like the Alamo siege evolve and expand. When it comes to revamping our state’s most beloved, most fought-over secular shrine, the stakes are high, and the challenges are clear: somehow the Alamo will have to find a way to honor both its mythic past and its messy present.

This article originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Alamo’s New Battle Plan.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Longreads

- San Antonio