This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Just past the northernmost edge of downtown Houston—past the rows of skyscrapers, past the cutesy redevelopments, past the old, decrepit buildings sitting along the banks of Buffalo Bayou, past even the bayou itself—there lies a small, weedy, 34-acre peninsula that has been created by an oxbow in the bayou. From Main Street, where the oxbow begins, it is difficult to make out the peninsula; it is hidden by bridges and concrete embankments and railroad tracks. These acts of man long ago obscured the act of God.

The peninsula is an industrial ghetto, full of old plants and older warehouses. Some of the rotting buildings are abandoned, and those still in use don’t look much better. The streets, full of potholes and weeds, are really just long driveways that dead-end behind the warehouses. The baked brown grass is littered with dirt and gravel and broken beer bottles. At the water’s edge the grass is taller and greener, growing wildly amid a tangle of trees and shrubs that gets thicker and more impassable with every step. The bayou is brown and murky, full of muck—and prone to flooding. From almost any point on the peninsula the Houston skyline is easily visible, yet you can’t shake the feeling that you are utterly cut off from the city.

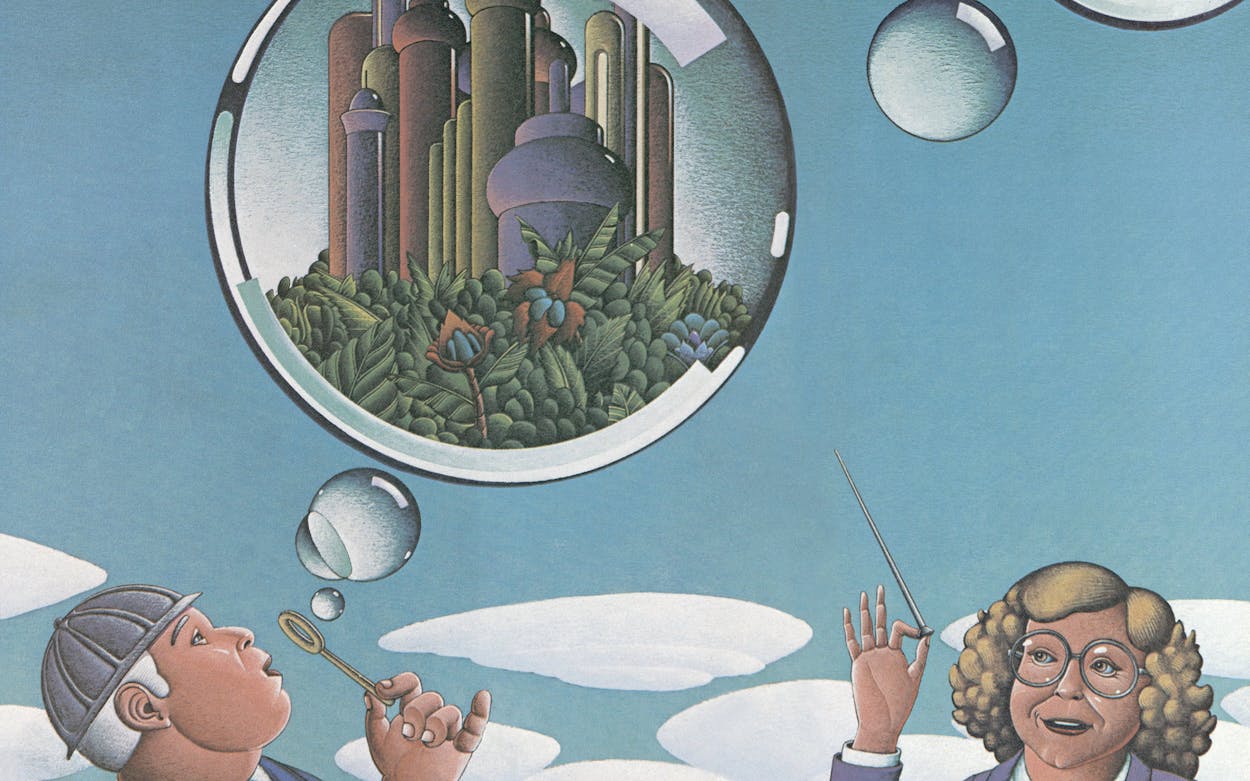

As it happens, a number of people have been looking rather intently at that peninsula during the past few years, and they don’t see the murky water or the decaying warehouses. They see something else entirely—an area magically transformed. Where there are 34 acres of peninsula, for instance, they envision 34 acres of . . . island. Fantasy Island, if you will. The island has been created by cutting a channel from one side of the oxbow to the other. The water level is low and steady: no flooding on Fantasy Island. The men eyeing this pathetic patch along Buffalo Bayou don’t see weed-ridden lots either. They see chic hotels and glorious, plentiful retail space, with high-priced shops and fancy glass-paneled shopping malls. They see high-rise condominiums. They see half a dozen office buildings, one or two as high as fifty stories. Down by the waterfront they see a touch of San Antonio—a lovely riverwalk paved with quaint brick and lined with sidewalk cafes and boat docks from which tourists can take little boat rides up and down Buffalo Bayou. And—who knows?—on those days when the imagination really runs wild, they might even see an MTA subway station on the island.

Who are these men who want to turn a peninsula into an island? Most of them are members in good standing of the Houston establishment—people like real estate developer Walter Mischer, former city attorney Jonathan Day, and architect S. I. Morris, head of the most politically well-connected architecture firm in Houston. During the administration of Mayor Jim McConn, they were “the golden boys” at city hall, to use Morris’ phrase. They knew the right strings to pull. They knew how to get things done. Once men like these had made the Houston Intercontinental Airport a reality and the Astrodome too. And in the process of bringing to life these civic amenities, they had made a little money too. They did good for Houston and so did good for themselves. Now they were going to try again.

For a while it looked as if Fantasy Island, a huge and complex development project involving both public and private money, had a fair shot at becoming a reality. But in November 1981 Houston elected former city controller Kathryn J. Whitmire to be its mayor, and all of a sudden McConn’s insiders could no longer find the right strings to pull, at least so far as city hall was concerned. Today, to their great disappointment, Fantasy Island remains a fantasy.

But does that mean that Kathy Whitmire is opposed to the creation of Fantasy Island? Well, no, it doesn’t. Even though not one demonstrable step has been taken toward the completion of the project since she became mayor, Whitmire takes a back seat to no one when it comes to proclaiming her unstinting devotion to the project. “I am convinced we can do it,” she says. But for Whitmire, up for reelection this month, Fantasy Island is a whole mayoralty in microcosm. Before she took office, the golden boys could pretty much have their way with city hall. Since then, she has seen to it that there are no more golden boys in Houston. Does that mean there won’t be any Fantasy Islands either?

Cocktails at the Club

It is October 1, 1981, less than two months before Whitmire’s election. Two dozen or so men and women are sipping cocktails and munching shrimp at the Plaza Club, high atop the One Shell Plaza building in downtown Houston. The Plaza Club often seems like the fraternity house of the Houston establishment; at this late-afternoon reception, the establishment has gathered to get a firsthand look at plans to beautify a lengthy stretch of Buffalo Bayou, all the way from River Oaks to Houston’s Fourth Ward. It surely needs beautifying. Houston has never been much for creating urban amenities—although it is the fourth-largest city in the country, it ranked number 140 in park space at the last official count—and its historic neglect of the bayous that run through the city is an urban crime. This is particularly true of Buffalo Bayou, the longest and most important of Houston’s eight bayous. Buffalo Bayou runs through the heart of the city, it offers a little geographic variety, and it has historic significance—the Allen brothers founded Houston along its banks in 1836. Yet it is a potential resource that the city has perversely buried over the years.

Before the Plaza Club reception is over, the guests will be asked to contribute to bayou beautification. Even without seeing plans or hearing presentations, they know that this is something they are likely to do, an inclination caused by a complicated mix of noble and selfish instincts. Everyone in the room realizes what an asset Buffalo Bayou could be, and everyone would genuinely like to see it become that asset. But they also realize that if Fantasy Island is the centerpiece of a bayou beautification plan, then almost everybody attending this affair will in some way profit from the project.

On the island there will be land to buy and sell, buildings to develop, and roads to build. But even those without a piece of the island will be able to profit from its development. Buffalo Bayou has always been the northernmost boundary of Houston’s downtown, a line of demarcation beyond which fifty-story high rises would never sprout. Fantasy Island, however, would turn the “wrong” side of the bayou into the right side. A fancy island development north of downtown would be a powerful magnet; inevitably, it would pull downtown toward it. In the process all that land in the northern part of downtown, now largely the preserve of derelicts and restorationists, would become infinitely more valuable. That point is lost on no one in the room.

There is another reason that the reception guests are likely to throw a little money at bayou beautification. Walter Mischer is behind it. Along with James Elkins, Jr., the chairman of First City Bancorporation, and S. I. Morris, the benevolent dictator of Morris*Aubry Architects, Mischer has helped organize this reception. They are McConn’s golden boys.

Mischer, Elkins, and Morris never do make it to the reception themselves. As their emissaries, they send Barry Goodman, the former head of the MTA, now a private consultant, and former city attorney Jonathan Day, who also has a reputation for knowing his way around the corridors of power. Since getting into the consulting business, Goodman has had as one of his chief clients something called the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation (S. I. Morris, chairman) a nonprofit entity created in the summer of 1980. At the reception it is Goodman who outlines the plans of the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation. What he unveils is pretty vague, but the drawings look nice. The island has been clearly delineated. Buffalo Bayou looks like an amenity. The people at the Plaza Club nod their approval.

Now it is Jonathan Day’s turn to speak; it has fallen to him, as the attorney for the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation, to make the pitch for money. He explains that funds are needed for a campaign to ratify an amendment to the Texas constitution that was approved by the Legislature in the last session. Like all constitutional amendments, this one must be passed by the state’s voters in a referendum, and it is on the November ballot. Proposition One, it is called.

What the amendment will do, Day says, is allow Texas cities to establish a complicated taxing mechanism called a tax increment district. If the referendum passes, the Houston City Council could create such a district in the area surrounding Buffalo Bayou. That would permit the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation to capture enough tax money to begin fulfilling its self-appointed task. No one in the room doubts that the people behind this plan have the clout to win approval from the city council. They ante up, mostly in chunks of $1000 to $3000. Mischer, Morris, and Elkins borrow $25,000 from Elkins’ bank and lend it to the effort. In all, more than $75,000 is raised.

The Plaza Club reception was supposed to be the starting point for the island’s development; instead it turned out to be the high point. A month after the fundraiser, Proposition One did pass; on the same day, Mayor James McConn lost his bid for reelection. Seven weeks after that, and ten days before Kathy Whitmire took over as mayor, the city council unanimously agreed to set up a tax increment district around Buffalo Bayou. The deal seemed greased. And then . . . nothing. Since then—since Kathy Whitmire has been in office—the tax increment district hasn’t collected a penny in taxes, and the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation has had so little to do that in effect it exists on paper only.

Parks Good, Island Better

The story of Fantasy Island begins in the late sixties, with a young landscape architect named Charles Tapley. Being a landscape architect, Tapley naturally looked around Houston at places that could use some landscaping, and there was Buffalo Bayou. Tapley was not the first person to notice how badly the city had treated Buffalo Bayou, but he was the most persistent, and by the early seventies the city was occasionally giving him contracts that allowed him to put his ideas on paper. They were “received with a yawn,” says Tapley.

His big break came in 1979, when the Wortham Foundation, the philanthropic arm of an old-line Houston family, gave the chamber of commerce about $500,000 as seed money to begin doing something about the bayou. The chamber hired Tapley to work up a master plan for four miles of the bayou (from Shepherd Drive to downtown, and later extending east to Hirsch Road). Tapley’s sketches emphasized parks, landscaping, and flood control improvements, not commercial development. But his plans also included the riverwalk and the island, ideas he had come up with in 1976 while teaching a course on the bayou at the Rice School of Architecture.

In the summer of 1980 Tapley presented his plan to the city council, which approved it unanimously. The council also allocated $1 million for construction of a demonstration park project on a small stretch of the bayou between Allen Parkway and Memorial Drive. The Wortham Foundation kicked in another $500,000 for the project. At the same time, the council approved Tapley’s recommendation “that a single purpose non-profit corporation be formed to guide the development” of his master plan. Thus was born the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation, S. I. Morris, chairman.

S. I. Morris likes to say he was the logical choice to be chairman of the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation, and there’s some truth to that. He is the vice chairman of the Houston Parks Board, a nine-member group that advises—and raises private money for—the city parks department. But Morris, a small, thin, courtly man of 69 who is known to everyone as Si, is also one of those Houstonians whose business interests are inextricably bound up in his civic activities. Being on this board or that commission brings Morris into contact with other influential people, some of whom are in a position to decide such things as, say, which architect should design their company’s new building.

Tapley’s plan had official city council approval, but Morris, the new bayou czar, had no intention of carrying it out exactly as it had been written. “It was not what I had in mind,” he says now. Instead, he latched on to the island as the way to make the deal work. And why not? Tapley’s plans had always stressed parks over development, and a decade later, all he had to show for it was a puny little demonstration project. If you were going to make the thing move, you had to get other players involved, and to do that you had to show them something besides trees and fountains. The island was the key partly because building the channel cut was necessary to control flooding. (As one Harris County expert put it, without a substantial flood control program, “the only thing you’ll be selling on the riverwalk is scuba gear.”) But more important, an island meant big-time development, and development was what tended to capture the imagination of the players Morris wanted to involve. A parks plan might be good for Houston; a parks plan and an island would be really good.

Morris soon began sending out signals that he was moving the project in that direction. He hired as his consultant not Tapley, the outsider, but Barry Goodman, an insider. Tapley was slowly being pushed to the sidelines. (“He was always butting his nose in,” says Morris.) Goodman, having just left the MTA, had a Rolodex full of the same names as Morris’ Rolodex; in Morris’ view, those connections meant that Goodman was a man who could make things happen. Another move Morris made was to ask Jonathan Day, who had strong connections at city hall, to handle the transformation corporation’s legal needs. Along with his new sidekick, Goodman, he began consulting regularly with Walter Mischer and James Elkins to get their blessing. (As Morris explained, Mischer and Elkins were members of an “executive subcommittee” that he had put together to get “private sector input.”) The emphasis began to shift from Tapley’s vision to Morris’ vision. People stopped thinking of the project as a bayou beautification project and started calling it a bayou development project.

Within months, Goodman had discovered that the island had very few owners, chief among them the Southern Pacific Railroad, which held about 40 per cent of the land, and Walter and Robert Hecht, the co-chairmen of the board of the Oak Forest Bank, who owned another 25 per cent. That meant that two big deals would capture most of the island acreage—much cleaner and simpler than having to make a thousand little deals with small landowners. And wasn’t it convenient that Walter Hecht was a close friend of Walter Mischer’s and that the Allied Bank, where Mischer served as chairman of the board, held some of the Hechts’ notes for the property? Goodman sent letters to the principal owners to find out whether, further down the road, they would be willing to sell their land. Letters came back: they would be, under the right circumstances.

Things started heating up. Clayton Stone, executive vice president of Gerald D. Hines Interests, one of the biggest developers in town, expressed an interest in Buffalo Bayou and the island. Joe E. Russo, a developer whose new 26-story Lyric Office Centre is the high-rise office building closest to the bayou, called Morris and Goodman and told them that he wanted to be a player. Mayor Jim McConn made it clear to Morris that he was on the team. Morris and Goodman began receiving letters from people like Don Rogers, executive director of the Downtown Houston Association (“I want dubs on the paddleboat concession”); and William Sharman, a small developer who has done some nice renovation work at the north end of downtown (“I had an excellent meeting later that morning with Mr. Mischer and found a most sympathetic ear”), and groups like Hope Development, a black consortium (“Hope wants maximum involvement in the bayou project”). The University of Houston Downtown, whose one-building campus sits on Main Street directly across from the island, signed on. It had an ambitious expansion plan that it hoped to have incorporated into Goodman’s plans.

With the help of the chamber of commerce, Goodman and Morris raised some money to cover the burgeoning expenses of the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation. Gerald Hines agreed to contribute $20,000. Shell Oil gave $10,000. About $100,000 of the original Wortham Foundation grant was turned over to the transformation corporation. In all, Morris and Goodman raised nearly $300,000 in 1981, of which $129,000 went to Goodman for his services. Tapley, meanwhile, received about $30,000 that year from the transformation corporation and never quite realized how far things had shifted from his original plan.

The Maximum Development Scheme

What would be done with the island once it was built was a subject of much discussion in those heady days. Goodman brought potential island developers together to kick around ideas. During one such meeting someone suggested that the entire city government be moved, lock, stock, and barrel, to the island. As later stated in a memo, “This would allow the city to sell the land it currently has City Hall on, which would be extremely valuable property, to an office developer.” Well, that was one idea that would never get past the kicking-around stage. Goodman, however, had come up with three development schemes—minimum, medium, and maximum—for the island. The minimum and medium plans would convert warehouses—“(where possible)”—into office buildings, and in so doing would raise the value of the property from between $6 and $15 a square foot to between $25 and $45 a square foot. In addition, the medium plan called for some low-rise condominium development. But Goodman’s heart really lay with the maximum-development scheme. As he put it in a March 1981 memo to Morris, “This development scheme would likely be founded upon a major high-rise hotel or hotels . . . [and] high-rise residential housing. . . . The office buildings would likely be in the ten to thirty story range with a fifty story or larger a possibility.” He went on: “An average property value would be $90 per square foot.” Here was Fantasy Island.

Who was going to pay for all this? Goodman and Morris had originally assumed that the island would be privately owned; as Morris told the city council, “It’s not something we would call on the city to participate in.” But it seemed unlikely that it could be privately financed. Just to create the island—digging the channel cut, making the necessary flood control adjustments, relocating Southern Pacific’s railroad tracks—was going to cost somewhere in the range of $40 million to $50 million. Throw in the riverwalk and the boat docks and landscaping—and streets and other necessities without which development was impossible—and you were up in the $60 million to $70 million range. And that didn’t even include the actual sale of land to developers, or the building of buildings, or all the rest of it. Seventy million dollars just to get the land ready!

Morris and Goodman knew full well that there was no one in Houston willing to put up that kind of money. The payoff to developers was too far down the road—perhaps years away. So instead, they promoted Fantasy Island as a “public-private partnership.” As they conceived it, the public partner would construct the channel cut, handle the relocation of Southern Pacific’s tracks, pay for the flood control program, and make the necessary improvements on the land—in other words, make the island developable. With that taken care of, the private partners would be happy to take over.

The main problem, then, was getting money from the public partner. To construct the channel cut, there was an obvious source of public financing: a Harris County flood control bond. The channel, as originally conceived by Tapley, was primarily a flood control device. Now the golden boys seized on that rationale. In a December 1981 meeting, county commissioners were “briefed on specifics of flood control improvement with emphasis on the diversion channel,” as Goodman later described it in a memo to Morris. (“It was my recommendation,” Goodman added, “that we confine our presentation largely to flood control considerations.”) County judge Jon Lindsay and the other Harris County commissioners eventually agreed that it was a worthy project; they added $13 million for the channel cut to a county bond referendum. In May 1982 the referendum passed.

Morris and Goodman thought they might have similar good luck at the federal level. Goodman talked to a number of federal agencies that hand out money for development projects. Tapley was even trotted out to give the dog-and-pony show to some federal bureaucrats who had come to Houston. He tried to take the officials—about fifteen in all—for a scenic ride down the bayou, but their boats promptly got mired in midstream. The lead boat, trying to get unstuck, showered the second one with gallons of muddy water. Alas, it was not a successful outing. Alas, too, not long after the formation of the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation, the Reagan administration came to power in Washington, and federal money became harder to get.

The Golden Boys Triumph

By the middle of 1981 Goodman and Morris had shifted their attention to another potential source of public money: tax increment financing, which allows a certain small section of a city—the tax increment district—to make municipal improvements now and pay for them with tax revenues generated later. The money comes from the higher taxes generated by the improvements. (The improvements lead to development, you see, which leads to higher property values, which means higher tax revenues.)

Tax increment districts are becoming increasingly popular across the country. They have been used to build a subway station in San Francisco and to improve utilities in Los Angeles, and in 1981 they came to Texas, in the form of a constitutional amendment pushed through the Legislature by Senator Ray Farabee of Wichita Falls. It wasn’t long before other people, in other Texas cities—including S. I. Morris and Barry Goodman—got interested in what looked like a promising new financing idea. Morris and Goodman realized that if Harris County could build the channel cut, tax increment funds could do the rest. With the money, they could build sewer lines and streets, and they could relocate the railroad tracks and create the riverwalk. Tax increment financing could build Fantasy Island.

To them, tax increment financing seemed to be the perfect solution. They would have to get the city council to designate the area surrounding Buffalo Bayou a tax increment district, but they didn’t think that would be much of a problem. And as long as Jim McConn was mayor, it was a pretty safe bet that he would appoint to the tax increment board the people who were behind the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation—the way tax increment financing works, voters have no say in who the members are or what they do with their funds. S. I. Morris stood a good chance of being the person most responsible for allocating the tax increment money, a significant bit of power.

And finally, most alluring of all, was the possibility that if Morris and Goodman moved quickly enough, they would be able to capture more than just future tax revenue. They would also be able to get their hands on some immediate tax money—money they could spend pretty much as they saw fit.

The reason for this was complicated. Under the 1981 amendment, once a tax increment district was created, the amount of tax money received by the city, the county, and the school board from the properties within the district’s boundaries would be frozen at that year’s level. For the life of the tax increment district, no taxing jurisdiction would get more revenue from those properties, no matter how much the property taxes increased. In theory, it was assumed that whatever tax increases occurred would be a result of the improvements made by the district.

In Houston, however, there was an extenuating circumstance, never anticipated by the 1981 constitutional amendment, that worked to the advantage of the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation: a long-awaited, long-needed tax revaluation of all the city’s properties was scheduled for 1982. Everyone in Houston knew that this revaluation would significantly raise property taxes, and indeed it did. The city alone gained about $17 million in 1982. A tax increment district set up before the end of 1981 would be entitled to all the extra money generated within its boundaries by the revaluation—which turned out to be a sweet $4 million a year, every year.

What ensued was a concerted push to set up the tax increment district before the end of 1981. The first hurdle was getting Proposition One—Farabee’s constitutional amendment allowing tax increment districts in Texas—approved by the voters in November. To that end, Day and Goodman set up a political action committee, called the Committee for Improved Communities and backed by Morris, Mischer, and Elkins. In October the Plaza Club fundraiser was held, and soon thereafter the committee was sponsoring ads extolling the virtues of Proposition One. In November the amendment passed, 473,000–339,000.

Then, with less than two months to go, what remained was to get the city council to agree to the creation of a district. There were two potential obstacles: Harris County judge Jon Lindsay and school superintendent Billy Reagan. If they opposed the tax increment district—and why wouldn’t they? it took money away from them—city council passage would become difficult.

The solution was simply to make sure there was something in the district for both Reagan and Lindsay. For Reagan it was a vocational school, to be built near the bayou with tax increment district money. Reagan agreed to support the district. For Lindsay (according to Goodman and Morris) it was a huge parking garage that would be built within a block of the county’s main office building, which is located on the banks of the bayou. Lindsay says that if such a plan was ever devised he never heard about it, but, for whatever reason, he made no move to stop the creation of the district. On December 22, 1981, Jonathan Day and S. I. Morris were able to go before the Houston City Council and tell the council members that neither Reagan nor Lindsay opposed the idea. The council unanimously legislated the tax increment district into being—with ten days to spare.

Day had another suggestion for the council. He recommended that as an interim measure the board of directors for the new tax increment district be composed of the members of the board of the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation. That, too, was approved unanimously. S. I. Morris was crowned chairman of the tax increment district. Fantasy Island was what they call “wired.” But it wasn’t to be.

Brave New Rules

Not long after the tax increment district was created the problems began. First, Judge Lindsay, who hadn’t said a word in opposition up to that point, started grumbling about the district. He decided that he didn’t like the city’s skimming off potential county revenue. Then the school board weighed in. It quickly realized that, because the district had been established in 1981, the schools were in a position to lose nearly $2 million in revenue. Then it learned that other cities within the school district’s jurisdiction—Bellaire, for instance—were also planning to set up tax increment districts, thereby making the potential revenue loss much more painful. Eventually the school board passed a resolution asking the city to abolish the tax increment district.

But most important of all, ten days after the passage of the tax increment district, Kathy Whitmire replaced Jim McConn as mayor. During her campaign Whitmire had come to represent, as much as anything else, a repudiation of the old ways of doing things. Mischer had lined up against her, as had a good number of the golden boys, but their opposition actually worked in her favor. They were McConn’s cronies; Whitmire had no cronies. Their mayor was a bumbler; she would be competent. Their mayor was a home builder, an amateur; she was an accountant, a professional.

Like Jimmy Carter, she was elected not so much because of what she was for, but because of what she was against. She was against the way city government had always operated in Houston—the same people pulling the strings, the same companies getting the contracts, the same small group of people profiting.

In the aftermath of her election, however, the people backing Fantasy Island had high hopes that she would line up behind the Buffalo Bayou Transformation Corporation. Jonathan Day went to see one of the mayor’s aides to talk about the tax increment district. As the aide recalls the conversation, Day asked some questions about Whitmire’s attitude toward the bayou project (she was for it, he was told), but he spent most of his time talking about the composition of the board. Were there people Whitmire wanted on the board, he asked. Did she want Si Morris to resign, for instance?

It was the wrong approach. Offering the winner a piece of the action was playing by the old rules. The new mayor was studiously uninterested in who served on the board. And it eventually dawned on Morris and Goodman, as their work ground to a halt, that she had no immediate plans to use the mechanism they had so painstakingly set up to make the project move—the tax increment district. They couldn’t understand why not.

To hear Whitmire and her aides explain it, the tax increment concept had a multitude of flaws that had to be overcome before it could be used in Houston. A court challenge to a tax increment district in El Paso put the whole idea of tax increment financing in legal limbo. How could Whitmire collect money for a tax increment district if there was a chance that it might be declared illegal? If a tax increment district did issue bonds, they would probably cost more in interest than general revenue bonds. What kind of sense did that make? A new mayor needed to be on good terms with the county judge and the school board, and collecting money for the tax increment district would be sure to damage relations. After the oil boom ended and Whitmire had to lay off city employees to keep Houston in the black, it became impolitic for her to set aside money for a big development scheme. And through it all, the new mayor was bothered by the way the district had been rushed through in order to capture the revaluation money. It offended her. In her view, that was not the intent of the constitutional amendment, and even if it didn’t violate the letter of the law (and it didn’t), it just struck her as wrong.

To Morris and Goodman, all of these flaws, except the political problem caused by the city’s money crunch, were quibbles, merely excuses for not moving ahead. When the new city attorney, Hank Coleman, sent Jonathan Day’s law firm a list of narrow legal questions about the district in mid-1982, the backers of Fantasy Island had a hard time taking them seriously. The mayor was stalling, they thought. When they heard about her objection to their plan to capture the revaluation money, they became even more agitated. How could she be worried about the intent of Proposition One? What they had done was perfectly legal and, to them, perfectly sensible. They had used the law to their advantage. If you were going to make things happen, that was precisely the sort of thing you did.

Morris and Goodman tried to get in to see the mayor, to talk to her about tax increment financing. In the fall of 1982 they drew up a proposed agenda for a meeting and then sent it to Whitmire’s aides. They got nowhere. “These guys didn’t even have a plan,” says one aide now. “She would have had a million questions that they didn’t have answers for. It just didn’t make any sense to have a meeting.”

They were frustrated at every turn. In April 1982, Goodman thought that the bayou project would soon be on its way and hired an associate to work on it full time. Seven months later he took her off the project; there wasn’t anything for her to do. Morris began answering queries about the progress of the bayou project with notes like this one to a member of Gerald Hines’ staff: “Our problem is that we haven’t been able to get the mayor going.” He no longer had access to city hall; he didn’t even know most of the people over there.

In March 1983 he received a letter from a former classmate of his at Rice, Knox Banner, now a Washington consultant. Banner had recently met with some of Whitmire’s staff, and he wanted to pass on to Morris what he had learned. “Mayor Whitmire has at least two Rice graduates who are key members of her staff,” Banner wrote, “John Chase, Assistant Director; and Jerry Wood, Director of Research. If you didn’t know them before, you now have three possible points of beginning [the other being Joanne Adams, the mayor’s assistant for cultural affairs, and another Rice graduate], but [proceed] very carefully, I suggest. . . . You may wish to seek more information on all three from the Rice Alumni Office before you strategize your gentle approach.” Even a Washington consultant had more access to Houston’s city hall than Morris did.

Still, where did that leave Fantasy Island? To McConn’s insiders it seemed dead in the water, and there was little doubt in their minds as to where the blame lay. Kathy Whitmire had killed Fantasy Island with her legalistic and picayune complaints. They tended to take this rather personally—they weren’t accustomed to losing—and it wasn’t long before a theory developed according to which the real reason Whitmire had shut down the tax increment district was because it was part of the baggage from the previous administration. Any project backed by Jim McConn and run by S. I. Morris, the theory went, was something Whitmire was going to be against, no matter what its merits.

There was a grain of truth to that theory. Morris “probably feels that way because he doesn’t have his personal plaything anymore,” Whitmire said bitingly when I talked to her. But she insists that Fantasy Island is not dead, and that in her own way, she has been working as hard to see it completed as he ever did. It’s just that Whitmire’s conception of working on it is a good bit different from that of Morris and Goodman.

For instance, she sees her hiring of a new planning director eight months ago as an action that is pushing the project along. The new man, Efraim Garcia, came from San Antonio’s city development agency; he says that when he took the job, Whitmire told him that the bayou project was to be one of his top priorities. (His familiarity with the San Antonio riverwalk is one reason he was selected.) So far, though, it is hard to see how that rather vague mandate is going to metamorphose into Fantasy Island. What Garcia has done for the bayou is what he used to do for San Antonio—play the game of federal grantsmanship. But to go that route is to resign oneself to the project’s being done only in the bits and pieces that fall comfortably within federal guidelines.

In fact, from Whitmire’s perspective, everything she has done so far—much of which has had the effect of stalling the project-has actually helped it. The legal queries—well, they had to be cleared up, didn’t they? The refusal to go along with the tax increment district—well, it did have an awful lot of problems, didn’t it? The shutting out of S. I. Morris—well, he did represent the bad old days of Houston politics, didn’t he? To her, this is not quibbling, it is good government.

If Whitmire ever does build a Fantasy Island, it will be on her terms, which means it will be the cleanest, most antiseptic, most apolitical deal you ever saw. And therein lies the trouble. Can you be completely clean, completely antiseptic, completely apolitical, and still build something of the magnitude of the island development? If you look at the great projects of Houston—for instance, the Ship Channel, which opened in 1914 and helped make Houston; the Astrodome, which first opened its doors in 1965; the airport, which opened in 1969—they were all deals from which insiders profited, to one degree or another. In retrospect, it seems pretty small-minded to begrudge them that, since such projects have obviously been boons to Houston.

But somehow, in more recent times, the delicate balance between noble instincts and selfish ones, which had always informed civic achievement in Houston, was tipped. The selfish-in the form of greed—has begun to outweigh the noble—the desire to get something good done for the city. Instead of doing good for themselves while doing good for the city, the civic achievers were doing good for themselves at the expense of the city.

When cable television came to Houston in 1980, it appeared that Walter Mischer and a few of his friends used the city’s power to grant cable television franchises mainly as a way to make money. The idea of bringing a first-class cable system to Houston never seemed to be a big part of the equation. After the dust had settled, they had made millions of dollars and the city was saddled with plenty of cable TV problems. The proposed MTA line also had all the earmarks of a deal that helped the few at the expense of the many. People in Houston have sensed this shift and have acted accordingly. They bounced McConn out of office and elected Whitmire. They trounced the MTA plan too. Both times, it seems clear that the electorate did the right thing.

And yet you’re still left wondering about Whitmire’s ability to get things done herself. Yes, she says she can make Fantasy Island a reality, but how? A mayor of a city as large and as messy as Houston is forever going to be handling the emergencies of the moment, while Fantasy Island goes to the back burner. A mayor with Whitmire’s mind-set is always going to be able to find legitimate nits to pick, while Fantasy Island gets put on hold.

Most important, a mayor with Whitmire’s background is always going to rank cronyism just after the bubonic plague on her list of evils. Whitmire’s vision of government makes no distinctions between what was good about the old way of doing things and what was bad. To her, it was all bad. But it wasn’t. It was bad when the city was the tool of the cronies; it’s not bad at all when the cronies are the tool of the city. That’s just good politics.

If Kathy Whitmire doesn’t want Fantasy Island to be S. I. Morris’ plaything—fine. There is no reason it should be, especially since Morris (and Mischer) are now supporting Bill Wright, her opponent in this month’s mayoral election. But it does have to be somebody’s plaything. In such a situation, she and the city would have the final say, but she could also leave the day-to-day negotiating to, well, to cronies. If she doesn’t want Morris, she should find one of her own supporters—someone like James L. Ketelsen, the head of Tenneco—and tell him: it’s your plaything. Give him—or someone—the authority to broker between the various interests and cut deals with the county and the school board. (And if that someone should happen to make some money in the process, that’s all right too.) If she wanted Fantasy Island badly enough, she would do that. She would put aside her distaste for cronyism—for the messy business of politics—to help make Fantasy Island a reality. If she did that, she would be doing good for Houston. And good for herself.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston