This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

An old Renault sped along on a system of interconnected potholes, shaky bridges, and deadman’s curves that was known in Madagascar as a highway. The driver, an urbanite from Antsiranana with a giddy temperament, swerved breathtakingly around taxi brousses and oxcarts. Passing through a forsaken little village of raffia huts, he beeped his horn at clusters of Malagasy children without bothering to slow down, expecting them to scatter like chickens. Every so often a foot-long chameleon—asphalt-gray for the occasion—would slip across the road in front of the car.

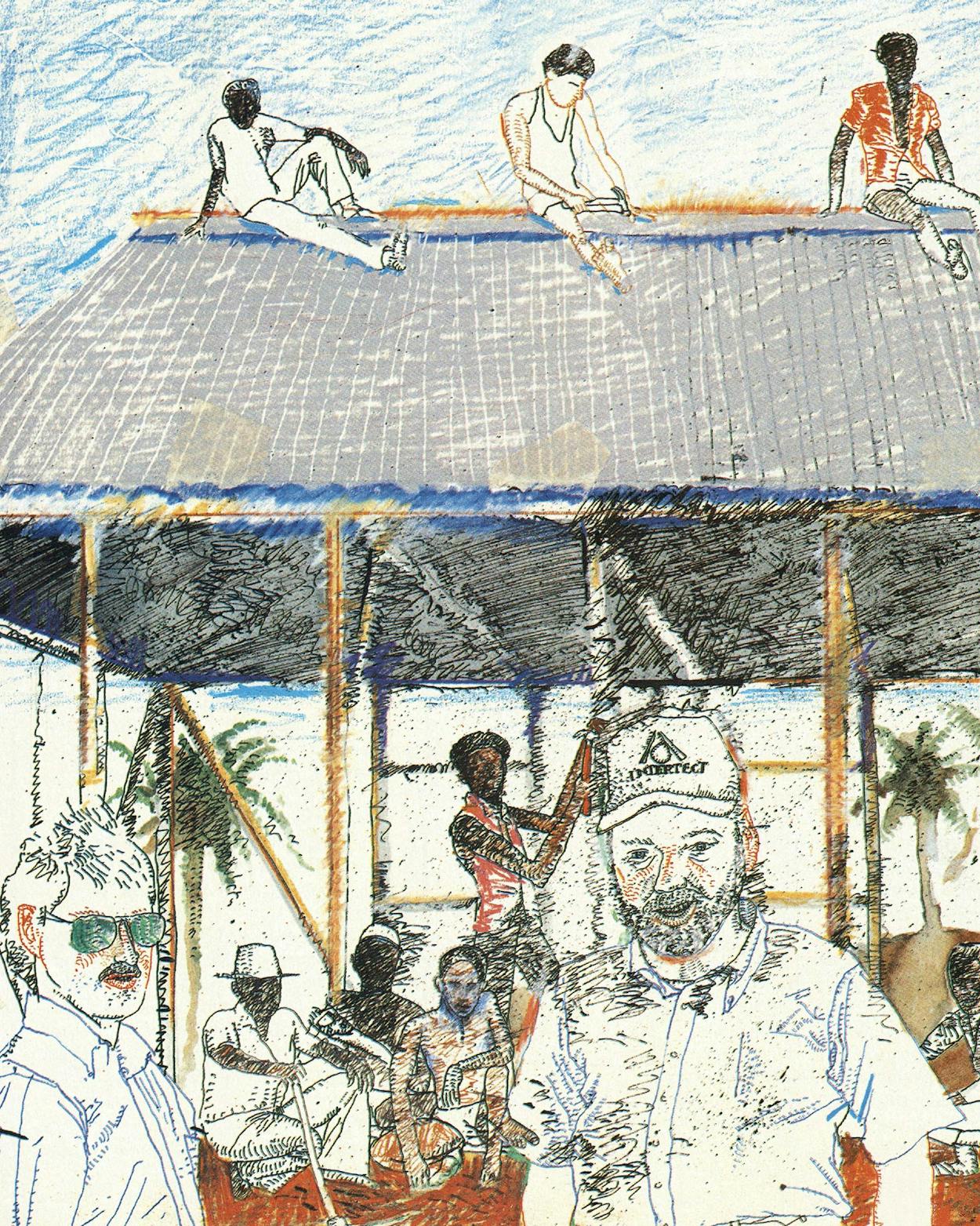

Fred Cuny, unfazed by the realities of Third World motoring, studied the landscape and remarked that it looked like West Texas. A big man in a small car, he sat placidly in the front seat, absorbing the road shock. A camera bag was balanced on his lap, and his round, bearded face was topped off with a cap bearing the name of his Dallas-based company, Intertect.

The country between villages was vast and empty. Madagascar, according to the few moldy guidebooks that exist on the subject, is shaped like a gigantic left foot. We were on the high northern savannah known as the Montagne d’Ambre, at about the cuticle of the big toe. The land here was marked by volcanic calderas and steep-banked creeks fringed with raffia palms. The roadsides were littered with uprooted trees and the shattered remains of houses.

Six months earlier a grand vent had passed this way. A cyclone named Kamisy had cut a swath through the northern tip of the island, made a wide U-turn out in the Mozambique Channel, and then hit the island again farther south at the port city of Mahajanga, prying off thousands of corrugated iron roofs and sending them whizzing through the air like scythes. In many cases the houses beneath—built of raffia, wattle and daub, or unreinforced concrete blocks—had disappeared as well, blown apart in the cyclone or washed away by the subsequent floods. Considering the severity of the storm, casualties had been miraculously light: estimates of the dead ranged from thirty to several hundred. But Kamisy had left tens of thousands homeless and had just about wrecked Madagascar’s already shaky economy.

It was the cyclone that had brought Fred Cuny to Madagascar. He was a disaster consultant, and as such he could be expected to turn up in various remote and devastated quarters of the world. Among the organizations that traditionally responded to a disaster, Intertect was unique. Unlike CARE, the Red Cross, and hundreds of other donor-supported charitable institutions, it was not a relief agency. It was a private consulting firm that provided such agencies, as well as other clients, like the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID), with advice and expertise.

Cuny had been hired by AID to make a damage assessment and provide technical assistance to the government of Madagascar in setting up a housing reconstruction program. Storm-resistant housing was Cuny’s specialty; he could talk far into the night about hurricane straps and torsion braces and the need for pitched roofs.

“You start out with good anchorage to the ground,” he was saying as we passed a ruined house that served as an object lesson. “Then you keep the walls up with braces in the corners. Then you have to have some kind of vent to let out the air pressure that builds up inside during a cyclone. The steeper the roof the better. You keep it on by nailing it and strapping it down with hurricane straps.

“I remember once in Jamaica we thought about having a poster made. It showed a picture of a beautiful girl in a bikini and underneath it said, ‘Strapless today—topless tomorrow. Use hurricane straps!’ ”

I held my breath as the Renault negotiated a rickety bridge spanning a creek where women sat in midstream, pounding their laundry on the glistening volcanic rocks.

“All these bridges haven’t been maintained since the French left,” Ron Parker, another passenger, said. “Believe it or not, this is the best road in the country. If you want to drive from Antananarivo to Mahajanga, it takes sixteen hours to go two hundred miles.”

“Anivorano’s unpaved streets were filled with older men in lamba skirts and wooden-wheeled carts drawn by humpbacked zebu cattle.”

Parker was a former Peace Corps volunteer who had worked for Intertect on several projects over the years. He had been in Madagascar for three months now, trying to set up the housing program in the face of endless bureaucratic snarls, funding problems, and materials shortages. The Malagasy government was eager for the program to work, but that enthusiastic support from on high was all too often spoiled at the local level by petty political concerns and a drift toward lethargy.

“In all my years in the Third World,” Parker said, “I’ve never run into so much ritualized inactivity. I say, ‘No more reports. I want houses going up.’ They say, ‘Fine. We’ll have a meeting to talk about it.’ ”

“I’m surprised your hair’s still brown,” Cuny said.

“I’ve got gray hairs. I really do. You know how many layers of bureaucracy this country has? You’ve got the national coordinating committee, the regional coordinating committee, two ministries for public works, and a department of housing. Then you’ve got all these other administrative levels. There’s the faritany, and under that you’ve got the fivondronana, and under that you’ve got the firaisana, and under that you’ve got the fokontany!”

Parker paused to catch his breath. His exasperation was good-humored, but so far the whole enterprise had been a trial. Madagascar itself was a mess. The socialist makeover of this former French colony had not been a success, and in the wake of the cyclone the country was destitute. Consumer goods were largely a memory. There was no cooking oil, no toothpaste, no machinery parts. If you wanted a new pair of soles for your shoes, you had to have them sewn on because the shoemakers had no nails. The few sawmills and cement factories in the country had been damaged by the cyclone, and there was no guarantee they would accept the government’s worthless currency. Short on tools and building materials and with no foreign exchange to buy them elsewhere, the reconstruction program had been hobbled from the beginning.

Cuny had spent the last few days in Antananarivo, the capital, talking to AID officials and representatives of the World Bank, trying to finance an extension of the original consulting contract and find some way to convert Malagasy francs into a usable currency. Things were starting to look up, but Parker was still scrounging in the nearly vacant hardware stores of Antsiranana, hoping to turn up a hammer or a screwdriver.

Creating a Boom

The open land gave way to forest. In a clearing not far ahead was the village of Anivorano, a community of perhaps a thousand people. A monument in the town square commemorated Malagasy independence. On a concrete slab that served as a marketplace, vendors were selling mangoes, dried fish, and piles of tiny desiccated shrimp. Cuny got out of the car and was met by a man in a trim khaki shirt. “Enchanté de faire votre connaissance,” the man said. “Je suis le président de la fokontany.”

“Enchanté,” Cuny returned, exhausting a significant amount of his French vocabulary. He had meant to take an intensive language course before he left Dallas, but the realities of a disaster-prone world had intervened. In the last two weeks, for example, he had been in Hong Kong consulting on its refugee problem and in India attending a conference on earthquake-resistant housing. Now, seemingly impervious to culture shock and jet lag, here he was in the backcountry of Madagascar.

Monsieur le président ushered us into Anivorano’s town hall, a compact building with a concrete floor and several rows of benches. A photograph of Madagascar’s president, Didier Ratsiraka, hung high on the wall, as if to afford the socialist leader the best vantage point from which to monitor the proceedings. Beneath it was a none-too-recent map of Madagascar, showing the immense island rippling the placid surface of the Indian Ocean, with the coastal strip of East Africa visible along the left side of the frame.

Cuny took a seat on a folding chair at the front of the room, leaving Parker the place of authority behind a battered metal desk with an ancient telephone. Seated there, Parker appeared to shuck his usual air of bemusement. He wanted to be taken seriously by these people, and as the members of the village committee filed into the room, he surveyed them with a stern, commanding look.

“ ‘The steeper the roof, the better,’ Cuny said. ‘You keep it on with lots of nails and by strapping it down with hurricane straps.’ ”

Parker had been to this village once or twice already to demonstrate building techniques and to explain how the reconstruction program would work. Intertect would train a group of village carpenters to build a cyclone-resistant house. Those builders would work with the village’s homeowners to repair or rebuild their homes. The workers would be paid a wage by the program, and the homeowners would be able to buy their materials at reduced prices. The object was not to flood the area with relief supplies but to set the local economy back on its feet—to create, in effect, a boom that would eventually benefit every stratum of the society. Today Parker wanted to negotiate the builders’ wages and to make sure that after a long series of delays the work was ready to proceed.

The people who filed into the room were dark-skinned with high cheekbones and straight black hair. They were Malagasy, descendants of the Indonesian wayfarers who discovered Madagascar in the first millennium after Christ and intermarried down through the centuries with the East African peoples across the Mozambique Channel.

A few of the older men wore skirts fashioned from patterned cloths known as lambas and ancestral straw hats that looked disconcertingly like fedoras. The others wore cast-off Western sportswear. One man carried a plastic bag filled with some kind of narcotic leaf, which he stuffed into his mouth by the handful until his cheeks bulged like a chipmunk’s. Another arrived wearing a fez and carrying a battered leather valise and a nineteenth-century cap-and-ball shotgun.

Parker spoke to them in utilitarian French, reviewing les techniques qui résistent le force du cyclone, and the président translated his remarks into Malagasy. French was the currency of international discourse in Madagascar, but the indigenous language, which shared its origins with the faraway dialects of Borneo, prevailed in everyday life. The président delivered his translation in a rapid slurry, the only syllable discernible to a Westerner being the occasional “ny.”

Parker told the workers he would pay 2000 francs (about $3) for a day’s work. When that figure was translated, they vacillated for a moment and finally proposed a counteroffer of 2500 francs.

“C’est cher,” Parker said. He made a show of mulling it over before agreeing to the price and then played his trump card: a prize of 25,000 francs for the builders of the house that he judged to be the most cyclone-resistant. At that news the workers’ wary reserve seemed to drop entirely. For most of them 25,000 francs was the equivalent of several months’ earnings.

After the meeting Parker went to inspect a house under construction while Cuny strolled through Anivorano’s unpaved streets, passing women with laundry baskets balanced on their heads and wooden-wheeled carts drawn by humpbacked zebu cattle. A group of children tracked Cuny at a respectful distance.

He was big, round-shouldered, rather slouchy. With his camera bag and his casual demeanor he looked like a tourist who had strayed—sleepwalking, perhaps—away from the designated routes. But in that very casualness there was something keen and alert, and Cuny poked around this distant human outpost with the unmistakable air of a man who was at home anywhere in the world.

“This is the way this whole street looked right after the cyclone,” he said, pointing to a heap of raffia panels and bent support poles. Cuny had come to Madagascar several weeks after the storm to do a preliminary damage assessment, and since then most of the materials from the wreckage had been salvaged and used to make haphazard repairs. Very little metal sheeting remained in the rubble. It had been bent back into shape and hammered onto makeshift house frames. Corrugated iron (or tôle, as it was called by the Malagasy) ranked with oil and cereals as one of the principal commodities of world trade. A house made of tôle was a universal status symbol in the villages and urban slums of developing nations. No one minded that the sweltering climate could turn a tôle house into a sweat lodge or that its rusted, ill-fitting panels had less aesthetic appeal than a raffia hut. Owning a metal house helped satisfy a Malagasy villager’s yearning for kinship with the industrial world.

Few of the repaired houses were any more cyclone-resistant than they had been before Kamisy struck. Ideally, Cuny’s reconstruction plan would correct that. A year or two from now, if all went well, the houses of Anivorano and dozens of other villages would be awaiting the next cyclone with cross-braced walls and strapped-down roofs.

Cuny joined Parker at a tôle shack that turned out to be a bar. They sat at a table in a dark room where huge fan-shaped bottles of homemade rum had been put by on shelves. Cuny poured some of the rum into a glass of flat Coca-Cola and sampled it.

“One of the greatest natural harbors in the world, Antsiranana looked untouched, as San Francisco Bay must have three hundred years ago.”

“Remember that rum in Honduras that tasted like hair tonic?” he asked Parker. “That’s what this tastes like.”

Cuny had a story from everywhere. There was the time he was caught in a PLO camp during an enemy attack, the time in Thailand when he masterminded the capture of dozens of Khmer Rouge cadre leaders who had been terrorizing a refugee camp, the time last spring when he was returning home from a disputed border with a footlocker full of body parts—which were to be tested for evidence of chemical warfare—and Lufthansa lost his luggage.

Cuny dispensed those stories with cocky enthusiasm. There was an appealing swagger to his manner; in the world of disaster relief he was something of a maverick. Back in the States he had compiled an information sheet about himself at my request. Under the heading “What Do My Critics Say?” he had written “Too pushy . . . won’t suffer the fools . . . (though I’ve mellowed a lot in last few years).” For “Kind of Image I Want to Project,” he set down, among other items, the following: “Tough—savvy—technocrat with social conscience and vision. . . . Not the kind to pick a fight, but not the kind to walk away from one.” He described his colleagues at Intertect as “tight-knit, handpicked, hard-charging mega-workers.”

Mother Teresa Weighs In

There is no question that Cuny has helped change the philosophy and dynamics of disaster relief. Intertect was the first to propose the use of satellites for monitoring floods in developing countries, the first to plan refugee camps as communities, the first to provide comprehensive evaluations of relief operations. Field workers for the big relief agencies are likely to be trained in programs that Intertect devised and to refer to manuals that Intertect wrote.

“I think he’s probably the most creative person in this business,” says Gudrun Huden, a program analyst for the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance, which has hired Intertect several times. “His is one of the firms whose motives I never have to worry about. That’s been tested many, many times. I’m aware that some people have found him on occasion to be arrogant, but I believe great people are entitled to a few minor failings.”

Cuny is a sixth-generation Texan, a descendant of the Cuny who died while performing as Jim Bowie’s second in the notorious sandbar duel. Another ancestor, in the family’s first recorded instance of attempted disaster relief, organized and outfitted the New Orleans Greys, most of whom perished in an attempt to aid the Texas revolution.

Fred Cuny himself first got into the disaster business when he was eleven years old. His parents had moved to a brand-new East Dallas suburb that had a tendency to sink out of sight during periods of sustained rains. Young Cuny, whose own house remained high and dry thanks to its fortuitous elevation, cruised through the streets in his sailboat, rescuing stranded homeowners and musing on the wisdom of building in a floodplain. When a newspaper photographer took a picture of the boy hero, Cuny quoted him a fee.

He had a passion for aviation. He earned his pilot’s license at sixteen and joined the Marines after high school, wanting to fly jets. But Marine pilots needed a college degree, so he took a detour to Texas A&M University, where he studied government and sociology. One summer he worked for a steamship company and traveled to South America, where he was struck by the social extremes: the wealth of the Church and the poverty of the churchgoers, the sun-drenched American enclaves surrounded by unspeakable slums. In Ecuador he was arrested while observing a riot and was held in custody at the yacht club. In Colombia he watched as a burning slum was bulldozed to contain the flames.

His experiences left him, in the jargon of the times, radicalized. He transferred to Texas A&M University, where he became involved in organizing laborers on the King Ranch and melon pickers in the Rio Grande Valley. After he left the Marines, he studied African development and public administration at the University of Houston and worked for a year in Eagle Pass for the Model Cities Program, then for the Fort Worth engineering firm of Carter and Burgess. In 1969 he took a leave and went to Africa, where he found himself in the middle of the Biafran relief effort, using the systems analysis techniques he had learned in his engineering career to help reorganize the airlift.

Cuny flew himself into Biafra in DC-6’s and C-97’s to see how the airlift looked from the receiving end, and he was horrified at what he saw. Conditions in the camps were miserable. People were getting sick from standing in the rain waiting to receive food. The latrines were inadequate; nobody knew how deep to dig them, and there was no manual to consult.

“It was enough to make me realize that the so-called experts didn’t know their ass from a hole in the wall. I thought that everything they were doing was counter-productive.”

He came back to the States and began writing pamphlets and field manuals on how to build better refugee camps and distribute aid. The more he studied traditional disaster relief, the more his fervor grew. With some exceptions, the big voluntary agencies—the “volags”—were dinosaurs. Too often they stormed into a disaster site with tents that nobody would use, with medicine that was out of date, with powdered milk that only exacerbated infant diarrhea, with instant mashed potatoes that the confused recipients tried to use as detergent. Traditional disaster relief, Cuny concluded, did little but create series of welfare zones, places where massive infusions of goods suppressed local economies and blunted the people’s natural drive to rebuild and reform. That philosophy of aid ignored the causes of disasters—the ancient tensions that created wars and refugees, the social inequities that situated poor people in floodplains and earthquake zones, the constant depredation of the landscape that created deserts and ceaseless famines.

“Antananarivo was a picturesque city. Its pastel stucco buildings huddled together on the slopes of the escarpment and on the broad esplanade.”

Cuny preferred to focus on disasters as opportunities for economic development and social change. He was not the only one with such ideas; most of the volags had their outlaw element, people who had grown weary of the agencies’ bureaucratic caution and quick-fix mentality. In 1970 Cuny and several other relief workers met in London and decided that what the world needed was not another agency but a consulting firm that would show the volags how to do things right. The name “Intertect” originally stood for “International Architects.” “Architects in the broad sense,” Cuny said. “We wanted to design and change the world.” Ever radical, he conceived his company’s corporate structure as a cooperative along the lines of an Israeli kibbutz. Later he refined it into its present form, a small private firm with a permanent staff of five, a modest office in Oak Lawn, and a network of consultants who are kept on retainer.

The company’s early years were touch and go (during one lean summer Cuny worked as a crop-dusting pilot), but eventually enough work came along to keep Intertect on its feet. Working for the relief agency Oxfam in Nicaragua after the 1972 earthquake, Cuny was struck by the fact that a moderate earthquake had destroyed so many houses and killed so many people. Why, exactly, had all those structures failed? Why had only poor people been killed? Why was the government bulldozing millions of dollars’ worth of salvageable materials in central Managua and throwing them into the lake?

He set about studying those questions, and in 1976, when a devastating earthquake struck the highlands of Guatemala, Intertect was ready. Working with Oxfam and World Neighbors, Intertect set up a grass-roots housing reconstruction program that became the model for other programs. Since then, Intertect has worked with disasters, man-made or natural, in more than thirty countries, for clients including Oxfam, the Red Cross, Save the Children, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and numerous foreign governments.

Intertect’s consultants tend to be professional types—architects and engineers mostly —who have managed to arrange a flexible enough work life to be able to fly to Sudan or the Solomon Islands on 48 hours’ notice. The money is nothing special—substantially less than they could make in their professions if they stayed put.

Cuny himself receives a modest salary from the company, and when he is not in a refugee camp or a slum on the far side of the world, he lives in a lakeside condominium in Rockwall. All in all, he seems to have fewer material comforts than a man who consistently sees the world at its worst might feel entitled to. There is a sense of commitment about him.

As the years have passed, Cuny’s outlaw gospel, his insistence on probing the root causes of disaster and of evaluating the effectiveness of relief efforts, has begun to take hold. But the gospel has not always been graciously received, or (the world having known greater diplomats than Fred Cuny) not always graciously presented. Intertect has been blacklisted in the past by some of the most prominent relief agencies, and then there was the time that Cuny found himself at loggerheads with Mother Teresa.

“That all started when I was in Calcutta working as an adviser for Oxfam. Catholic Relief Services came to me with this plan for a three-phase housing program that started with tents, then upgraded to metal houses and finally to concrete. I told them I wouldn’t recommend it to Oxfam. It was poorly written and inappropriate; it didn’t take into account the indigenous housing. The next week, I came in from the field one day and all the secretaries in the office were wearing their best clothes. They said, ‘She’s here.’ So I go into this room, and there’s Mother Teresa. She said she understood I knew a lot about housing and wanted to learn from me. So I told her all the stuff we were trying to do, and she listened very patiently, and then when I was through, she pulled out this CRS proposal and said, ‘So fund it.’

“I told her, ‘Mother Teresa, there’s no way I’m going to recommend that project. For one thing, there’s not enough stability—all that concrete would just sink into the mud.’ She said, ‘All right, I’ll just have to call my friends at Oxfam.’

“There was really awesome pressure on those people, but they didn’t cave in. After she won the Nobel prize, I happened to be in London, and some relief people invited me to go with them and hear her speak. I was sitting up in front, and she starts talking. ‘I’m happy to accept this prize on behalf of all the poor and downtrodden,’ et cetera, et cetera, and ‘I’m grateful for all your help. In all the years I’ve worked with humanitarian agencies, no one has turned us away.’ Then she pointed right at me in the front row and said, ‘Except for this man right here!’ ”

Houses of the Dead

It was late afternoon by the time we left Anivorano. The road that led to Antsiranana passed through several smaller villages. Parker wanted to stop at each of them to introduce himself to the local président and explain how the reconstruction program would work. The first village was a cluster of palm huts huddled against the steep bank of the forest, as much a pure expression of the natural world as a series of termite mounds. The people who lived here, its président told Parker, had fled into the forest when Kamisy came. When they returned to their village, they found it destroyed. Complètement.

Village by village, the little Renault climbed higher onto the plain. The bare volcanic forms loomed more prominently against the darkening sky, and unrecognizable things crept across the road. The last stop was at a fairly prosperous community of tôle shacks that hugged the eroded shoulder of the highway. The président was young and solemn. He had no shoes, but he wore a black suit coat over his bare chest. His family and constituents crowded nearby in the failing light, wanting to listen and to shake hands with the visitors. In the doorway behind them a man struggled to light a kerosene lantern, and when he finally succeeded, the light exposed a crowded display of brightly patterned lamba cloths, their colors supernally vivid against the drab metal shack that contained them.

Twilight in Madagascar. Despite its superficial resemblance to West Texas, the landscape possessed an enthralling strangeness. The volcanic shapes here were fairly recent, but the underlying basement rock was possibly the oldest thing of any kind on earth. The island, which was larger than France, had rafted away from what is now the East African coast during the breakup of the primeval continent of Gondwanaland 180 million years ago. Among the creatures the island took with it were lemurs—a genus of fox-faced primates that now reside nowhere else in the world—and a gigantic bird called the aepyornis, which, according to Marco Polo, preyed on elephants by snatching them into the air and dropping them onto the rocks below. In reality, the aepyornis was unable to fly. It was bigger than an ostrich, and one aepyornis egg could feed fifty people.

Pieces of those eggshells could still be found, but the birds themselves were gone. They had no chance once the first humans arrived and woke the island from its long sleep. The light, arboreal lemurs soared away into the diminishing forests, but the ground-based species—some the size of orangutans—survived no longer than the luckless aepyornis.

The Malagasy themselves flourished, evolving a rich and spectral culture centered upon an elaborate consideration for the dead. We could see evidence of that preoccupation as we traveled to Antsiranana. On the side of the road were tombs built of cinder block, a precious material in this destitute region. The houses for the dead were made to last longer, and look finer, than those for the living.

The dead were called the razana, “the ancestors,” and in rural Madagascar, where the old thinking still held sway, there was nothing more crucial than their contentment. The dead were the intercessors for the living in the next world. They were owed fealty and respect. They expected, from time to time, to be taken out of their tombs, brought into the fresh air, wrapped in new burial shrouds, and paraded around the village while their living relatives feasted in their honor. In addition to his obligations to the dead, a true believer had to contend with a complex variety of taboos, known as fady, that ruled almost every aspect of every day. It could be fady, for instance, to lead with the wrong foot when crossing the threshold of a house, to shake hands with your sister, to harm a chameleon. In parts of Madagascar it was fady for a man to wear shoes while his father was still alive.

Pot of Gold

I can’t believe it,” Cuny said when he arrived at the hotel verandah the next morning for breakfast. “The maid just propositioned me for a tube of toothpaste.” He shook his head and looked out at the harbor of Antsiranana, a vast bowl of deep blue water protected by low barren hills, with a faraway notch leading out to the Indian Ocean. It was one of the greatest natural harbors in the world, and on this bright morning it looked untouched, the way San Francisco Bay must have looked three hundred years ago.

Antsiranana was still widely known as Diego-Suarez, the name it bore until independence in 1960 and the “Malagasization” of all Madagascar place names. The name harked back to a sixteenth-century attempt by the Portuguese to control the island, a bid they ultimately lost to the French. Later, Diego-Suarez was one of the many pirate haunts along the Madagascar coast.

The harbor was also the graveyard of most of the Malagasy navy, whose few vessels had been berthed there when the cyclone hit. Antsiranana itself was heavily damaged, and six months after Kamisy had struck, the center of town was vacant and hushed. The balmy colonial architecture was in ruins, a monument to a vanished civilization.

Antsiranana, as well as its outlying villages, was a target of the reconstruction program, but in the two weeks Parker had been here he had met with little but frustration. The bureaucracy had been dragging its feet about its promise to provide a local director and staff for Parker to train, a need that had to be met if the project was ever to become self-sustaining. In addition, the building materials that the program was introducing into the economy brought along their own complications, since where there was wealth to be distributed, there were dozens of petty bureaucrats cautiously waiting for an opportunity to claim credit.

“When you come in right after a disaster,” Parker said as we drove to the airport to catch a flight to the west coast city of Mahajanga, “it’s totally different. People work together. But when you come in five months later, you find that everybody’s been sitting around figuring out how to get their hands into the pot of gold.”

Parker and Kent Hardin, Intertect’s other representative in Madagascar, had been shuttling between Antsiranana and Mahajanga for three months now, trying to keep the program alive while waiting on funds and on the inscrutable hemming and hawing of various officials. Hardin was in Mahajanga now, finally supervising the construction of the first few model houses.

The cyclone had taken most of the roof of the Antsiranana airport, and the flood of sunlight that spilled onto the concrete floor redeemed some of the place’s drabness. Shrimp cakes and mangoes, as well as bottles filled with pickled cabbage, were for sale at a small booth. Air Madagascar, the government airline, consisted of two 737’s, a dozen prop-driven Twin Otters, and a 747 that its creditors were threatening to repossess.

The plane rose over the brilliant harbor and flew for a time above the great plateau that was the island’s dominant feature. The terrain below was a sea of soft denuded hills. There were rivers, broad and choked with mud, and innumerable drainages that marked the landscape like the veins of a leaf. Once, the land below had all been a dense, humid forest with only occasional clearings for lakes and peat bogs, but a thousand years of slash-and-burn agriculture had turned it into a desert.

Westward from the plateau, the land sloped gradually down to the sea. Mahajanga sat where the Betsiboka River emptied into the Mozambique Channel through the wide sluice-gap of its delta. The outgoing tide was a formidable daily occurrence, silting up the harbor and muddying the clear water for miles up and down the coast.

Getting to Know the Lemurs

Mahajanga is really not that awful,” Kent Hardin said, smiling bravely as he greeted Cuny at the airport. He was tall and dark-haired, a native of Ponca City, Oklahoma, who had spent most of his childhood in Africa, where his father was a teacher. When he spoke, there was the suggestion of a clipped, Stewart Grangerish accent.

“All this was under water during the cyclone,” Hardin said as he drove us into town through a broad floodplain littered with debris. “There was a government housing project here.”

The air that hung over the city was so moist one almost needed gills to breathe it. Beyond the floodplain, lining the road, stood a long series of decrepit vendors’ booths that shimmered in the liquid atmosphere. A charcoal-maker’s house stood nearby, a sooty, dilapidated hutch surrounded by chest-high black mounds. The Land Rover lurched from the precipice of one pothole to another as Hardin made his way through streets crowded with zebu carts and rickshas, whose drivers ran barefooted through the streets, the weight of their passengers seesawing them upward so that their feet seemed to barely touch the ground.

Downtown Mahajanga was largely a ruin. The streets were lined with twisted metal and fallen stucco. Most of the roofs were gone, and there was no material to replace them. The late-morning glare made the empty and colorless French buildings look as dry as bones.

His months in Mahajanga had sharpened Hardin’s appreciation of the absurd, and as he drove he launched into the same sort of exasperated litany that Parker had recited the day before.

“The people here love paperwork,” he said. “The Malagasy word for paper is ‘taratasy.’ You hear it all the time. ‘Taratasy. Taratasy. Tsy nisy taratasy’—no papers. It’s their favorite expression. The word they have for ‘foreigner’ means ‘the man who shows his papers.’

“A lot of odd things go on here. Nobody disagrees with you in this country. Everything is yes, yes, yes. It doesn’t mean ‘Yes, I’ll do it’ but ‘Yes, I won’t make trouble for you.’ You can say to them, ‘I need an astronaut. Are you one?’ ‘Yes, I’m an astronaut.’ I told them I needed carpenters, and I got people I had to teach how to drive a nail.

“But then,” he went on, “you might go into one of these shacks and find somebody on the floor doing differential equations. They’re so eager to learn. I guess the only capital these people have to develop is their dreams.”

Hardin and his Malagasy carpenters had managed to build the frames of two cyclone-resistant model houses. We were on our way to visit the first of them, in a neighborhood called Ambovalat. The frame stood on a slight eminence, the only new and hopeful thing in that squalid environment. The builders were gathered about it, eager to show it off to Hardin’s boss, who had traveled from America to see it.

A dozen workers crowded around Cuny to shake hands. Each one offered his hand with an enthusiasm that suggested the gesture carried for them a significance beyond courtesy.

They watched Cuny nervously as he inspected the frame. The carpenters had hammered hurricane straps and braces in every conceivable place. Clearly, this house was not going to blow away.

“I wanted them to build the wall lower,” Hardin said, “but these people will just not do that.”

“Well,” Cuny said, “if it’s going to be that high, it’s got to have good solid connections to the ground. Also, you ought to argue some ventilation ports.”

He backed away a little to take a final look.

“Are they expecting me to say something official?” he asked Hardin.

“I’m sure they’d appreciate it.”

Cuny turned to face the workmen, who were gathered inside the house, studying him through the unfinished walls.

“Bonjour,” he said. “Tell them I’m glad to be here, and I’ve come here especially to see their work and how well they’re doing. Tell them the government is very interested in the project. I will inform the government of their progress. In many ways they are pioneers in the construction industry. Tell them that when the program ends, they’ll all look back with pride at what they’ve accomplished.

“And now I’d like to shake their hands in gratitude.”

After the visit we drove back into town for lunch. The restaurant looked out over the wharf, where half a dozen schooner-rigged dhows, called goélettes, were tied up, as well as a big metal-hulled vessel about the size of an oceangoing shrimp boat. Its crew, according to Hardin, had recently removed its engines and inexplicably replaced them with a pitiful sail the size of a bed sheet.

At low tide all the water drained away and the boats rested on mud. The dockside facilities at this vital port seemed to consist of a zebu cart and a sleeping driver. Most of the materials that Intertect had received so far—chiefly lumber from the east coast port of Toamasina—had arrived here, carried on those same goélettes.

The restaurant was named the Ravinala, which is the Malagasy word for the traveler’s palm, whose fan-shaped fronds, along with the long, parenthesis-shaped horns of the zebu, compose the official iconography of Madagascar. The unsightly mounted head of a zebu was hanging like a trophy from the wall of the restaurant. It had a bug-eyed look of disapproval.

Studying that apparition, Hardin remarked that it was a local custom to slaughter a zebu at the beginning of a construction project. The best place to do that was on the shores of Lake Anivorano, where the spirits of the ancestors resided in the forms of crocodiles. A few chunks of zebu haunch went a long way toward appeasing them.

“We’re looking into that,” Hardin said. “A zebu costs about two hundred dollars. We’re going to throw a shindig up there with eau gaseuse and zebu.”

A waitress brought platters of grilled prawns and bowls of Chinese soup. She picked Cuny’s Intertect cap up off a chair and set it at a coy angle on her head.

“C’est très jolie,” she said.

“It’s a, uh, friendly country,” said Hardin.

There followed a discussion of cement. Hardin was of the opinion that it should be one of the building materials that Intertect made available to the residents.

Parker disagreed. “We wouldn’t ever be able to get enough cement to allow people to build walls. Besides, we’re a month away from the rainy season, and these people don’t have roofs.”

“When the rainy season comes and you have a dirt floor,” countered Hardin, “you’re living in a soup.”

Cuny hung back, listening. As a matter of course, he gave his project directors a remarkable amount of autonomy in the field, and now when he was here with them, he did not seem to want to interfere.

“I agree with Ron,” he finally offered, “that we’ve got to get roofs up. But I also agree with Kent that we’ve got to keep our options open. You watch—in two weeks, when you’ve got houses up and people working, you’re going to have politicians jumping in to take credit for it.”

For now, though, the politicians were keeping their distance. The local governor was not in his office when Cuny stopped by later that afternoon, so he and Hardin drove out to check on the progress of a model house in another neighborhood and to drop in at the office of the shipping line, which had at last received the tôle Intertect had ordered.

They passed ruined hotels, eroded statues, blighted colonial mansions. At the waterfront stood a giant baobab, so swollen and leafless it looked less like a tree than like some monstrous tuber that had burst forth from the ground. The reek of spoiled fish and sea wrack pervaded the air, and in the crowded streetside markets the stench of untreated sewage from the nearby slums mingled with the high smells of fruit and moldering meat.

Under their square white umbrellas hundreds of vendors were selling bananas and mangoes, pastries, used shoes, and cheap tablets and pencils. Some sold automobile parts—little things like bolts and gaskets and leaf springs, which they arranged upon their lamba ground cloths with finicky attention, as if they were displaying jewelry.

Toward the end of the afternoon, Hardin stopped at one of the stalls and bought a bunch of blackened bananas. Lemur food, he explained.

The lemurs lived five or six miles outside of town, around the ruins of a French biological station. It was a lush, evocative place that the jungle had done a good job of reclaiming.

“Bon soir,” Hardin called to the woman who emerged from the main house.

“Voulez-vous voir les lemurs?” she asked. She turned around to the forest behind the house and began calling, “Coooot! Coooot!”

The lemurs promptly emerged, bounding in the distance from tree to tree like their monkey cousins. They settled in the trees before us and waited patiently to be offered bits of bananas. The dexterous animals took the food without grabbing. Flashes of primate fellowship passed between us, but ultimately the lemurs began to seem more and more alien. With their protohuman body language and canine snouts, they made me think of little men who had been transformed into wild creatures by some evil spell. When the bananas were gone, they stared down from the trees with an air of mild curiosity.

“You’re probably wondering,” Hardin said to them, “why we called you here. We want you to all have cyclone-resistant trees.”

Mahajanga After Hours

I really get pissed off when people send inappropriate aid,” Fred Cuny said. He was talking about tents and blankets.

“It’s not the tent itself. In certain situations tents are very useful. It’s what the tent represents. It satisfies the needs of the donor but not necessarily the needs of the recipient. You give them a tent and they expect a house, but if you give them tools, they get on with the rebuilding.

“A lot of these agencies are still in the mind-set of ‘Oh, that poor suffering victim. Let’s send him a blanket.’ The realities of disaster aid are a lot more complicated. It’s about how to plant a hybrid seed using manure instead of fertilizer, how to change the mesh in the fishing net so it’s big enough to let the little fish escape.

“Let me ask you a question,” he went on. “Do you need a blanket here?”

We were sitting in the open-air restaurant of the Hôtel de France, the only hotel still operating in Mahajanga since the cyclone. The city had once been one of Madagascar’s few tourist spots; the more prosperous citizens from the capital would come here to stay in beachside bungalows that Kamisy had left in ruins.

The Hôtel de France was the cosmopolitan hub of Mahajanga, a place in the dark and deserted core of the city where Japanese fishermen, German engineers, Russian military advisers, and American geologists could come to drink, eat lobster flambé, and watch a parade of very available-looking women.

Cuny went on about the inappropriateness of much of the medical relief that had come to Madagascar after the cyclone. While he talked, a gecko barked like a tiny dog in the stillness outside. I sensed something moving on the floor and looked down to find a large rat stationed companionably against my shoe.

“Disease goes down after cyclones,” Cuny said. “The floods clean out the water. The salt does a lot to clean out bacteria. The rain cleans out the trees and helps get rid of the mosquitoes and flies. Everybody’s always worried about cholera. There’s no evidence that the incidence of cholera is increased by a cyclone.

“One of the things that are criminal about some of these agencies is they’ll give all these kids injections and there’s no follow-up, no tracking. If you only give the first shot and not the rest, you just wipe out the immunities.”

Cuny was not entirely critical of the big volags. He thought some of them, such as Oxfam, CARE, World Neighbors, and the Mennonite Central Committee, were generally responsive to new ideas and were efficient in terms of delivering reasonably appropriate aid. But for every such agency, there were others that had no idea what they were doing, the sort of groups that were providing disaster victims in the Third World with used panty hose and canned asparagus.

He was firmly opposed to the foster child approach, wherein an agency takes a donor’s money and uses it to sponsor a particular child. “If you focus on the child, not the family,” he said, “the whole thing absolutely sucks. The child who gets singled out ends up abused and resented. A lot of times he’s bringing in more money than the head of the household. Americans want to believe that the problems are simple. People will sit there and brag to me about the kids they’re giving five dollars to around the world. Well, a kid with five dollars in a place like this is a target.”

After dinner we walked through downtown Mahajanga. Before the cyclone this area had teemed with street life, but now it was empty and unlit. It was like a wartime city that had been bombed into rubble. Rickshas were parked here and there on the edges of the streets, and from those vehicles the drivers had rigged lean-tos to shelter their sleeping families.

We followed the Crépuscule, a broad sidewalk parallel to the sea. A few big ships were anchored in the distance, away from the shallow, silted-up harbor, and the wavering lantern of an outrigger was visible as the boat shadowed the coast. Otherwise, the Mozambique Channel was as dark as the abyssal depths that lay between here and Africa. It seemed fitting that those waters were the home of the coelacanth, an armor-plated, brutish-looking fish presumed to have been extinct for 165 million years—until one turned up in a fishing net in 1939.

The Crépuscule, except for two presidential policemen in red berets and a group of Malagasy girls who offered giggly bon soirs as they walked by, was deserted. Most of the nightlife seemed to be concentrated at a little disco near the wharf. Outside, men who had been hired to protect cargo slept atop bales and piles of lumber while the Madagascar night was pierced with the sounds of Cyndi Lauper singing “Girls Just Want to Have Fun.”

Inside, the club was jammed with foreign operatives of all stripes and glamorous high-cheekboned women. Cyndi Lauper gave way to some nameless off-brand rock ’n’ roll as a strobe froze snippets of existence in a white flash that was as furious as heat lightning. What really brought the revelers to life, though, was, of all things, an old Glenn Miller medley. About the last thing I ever expected to witness was a barful of people in the middle of Madagascar chanting out, drunkenly, in unison, “Pennsylvania-Six-Five-O-O-O!”

When we left, the cargo guards were still sleeping. Hardin and Parker hoped we might catch a glimpse of King Tut, a man (or woman—nobody was quite sure) who patrolled the streets of Mahajanga in lonely splendor, dressed as an Egyptian potentate. But he never materialized. Instead, a group of Malagasy prostitutes followed us for a time through the dark streets, calling out, in French, “Have you had your dessert?”

“It’s hard saving the world,” Parker said.

In the Catbird Seat

A second model house was under construction in a Mahajanga neighborhood called Abattoir, which was named after a nearby slaughterhouse, Abattoir was a dense warren of dilapidated metal hovels and dirt streets bordered by open sewers clogged with trash. Malnourished children ran through the streets playing with crude toys—a bottle cap slung about on a string, a series of coat hangers bent to form the steering column and two front wheels of an imaginary car.

Cuny was anxious that work at Abattoir begin in earnest. Now that the building materials were beginning to arrive, it was important that houses start going up. The program had been in the doldrums for too long, and it was in danger of being perceived as another unfulfilled promise. What Cuny and his colleagues wanted was activity. As long as the project was stalled, a hundred petty officials could sit on their hands, gauging its patronage value to them while doing nothing. Once it was successfully under way, the construction program would have a momentum that could not be ignored.

The next afternoon, Cuny and Parker drove to the Abattoir site. The model house stood next to a heap of bent sheeting and mangled benches, the ruins of a schoolhouse that had been destroyed by the cyclone. The construction crew was happily at work. The frame of the house was finished, and three or four workers were on the roof hammering sheets of tôle into place. Others cleared away mounds of dirt with cheap, flat-bladed shovels, the only kind that the Intellect team had been able to obtain.

The carpenters, young men in their early twenties, had been working on this house for two weeks. Experienced framers could have done the job in two days, but it seemed unlikely that they could have derived the same pride of accomplishment.

Cuny and Parker had decided that the workmen should finish the model later and go out into Abattoir to repair and rebuild their neighbors’ homes. Just as at Anivorano, the program would provide the tôle and other materials to the homeowners at a reduced rate and would pay the carpenters daily wages to supervise the construction.

“It is necessary to make something now,” Parker told them in French. “You have plenty of wood. If you’re ready to build something, I’ll give you the tôle.”

The group, upon hearing this, was curiously impassive and noncommittal. They talked among themselves in Malagasy, and several others spoke to Parker in cryptic, imperfect French.

“I’m not understanding something,” Parker said to Cuny. “They say they can’t build now, but I don’t understand why.”

The discussion went on for some time, but the workers’ ambivalence remained as mysterious as ever. Finally, Parker asked them to at least show him some houses that needed repairs. This they seemed eager to do, and they led him into the heart of the neighborhood.

Scrofulous chickens scattered as the procession made its way. Malagasy matrons, some of whose faces were speckled with a sulfur-yellow cosmetic powder, peered over fences made from rusting tôle. The afternoon light was beginning to fail, and the smell of burning charcoal seemed especially sharp. The group stopped at a concrete slab inside a kind of courtyard. It had once supported a house, but now all that was left of the original structure was a neatly stacked pile of support poles.

“There’s a lot of wood here,” Cuny said. “Good wood.”

“Ici!” Parker told the workers. “Here is where we will start.”

The workers were not moved. Even the owner of the slab was not enthusiastic. He said he did not have the money to buy the tôle that was needed to repair his house.

“I will give a donation of twenty-five thousand francs’ worth of tôle,” Parker answered.

One of the other men said he had already hired workers to help him repair his house.

“Fine,” Parker said. “We’ll help you pay for the labor. We’ll pay the workers! We’ll donate the money! We want to start the repairs now!”

Silence. Finally one of the men spoke up.

“He says they need a week to make up their minds,” Parker reported to Cuny in a bewildered voice. “Do you understand what’s going on? Tell me.”

“It’s the early crisis of confidence,” Cuny answered. “They’re just not quite sure yet.”

“I’ve said I’ll pay the whole group to repair anybody’s house. I’ll donate twenty-five thousand francs’ worth of materials. There’s something that hasn’t been said. I don’t know what it is.”

Parker turned to them again and kept pressuring them, trying to understand their reluctance. One man said his grandmother had forbidden him to participate. Another said he could not help with the project because he was only visiting from another neighborhood. But the truth slowly emerged.

“Okay. Now we’re getting to it. The mayor of this district wants them to build his house first. That must be it. The resistance I’m getting could only be explained by politics.”

“Allons!” he told the group. “Allons voir le président!”

The workmen were suddenly galvanized with enthusiasm. The whole group, following Parker, charged through the streets of Abattoir to see the président of the fokontany.

The président was a thin middle-aged man in a faded red shirt. He greeted his visitors with deference, but there was a smug look on his face.

“He’s in the catbird seat and he knows it,” Cuny said.

The office of the président contained an iron-framed bed and a table supporting a battered Remington typewriter. People were crowding in at the open window and doorway.

The président gave Parker a handwritten list of 25 names on rough Malagasy notepaper. Not only did he want his house built first but he also wanted to make sure that his friends came next.

“Maybe what you ought to do is make a deal with the mayor to build his house and drop the other twenty-four,” Cuny suggested.

“At this point,” Parker replied, “I’d build a house for Satan’s grandmother if it would get the construction started.”

What Parker finally told the président was that construction on those 25 new houses could not begin until after existing houses had been repaired. Would the président do him the honor of choosing which houses should be repaired first?

Pleased by the deference to his authority, the président agreed and led the delegation into the streets and to the damaged house of a constituent.

“The group comes here tomorrow,” Parker announced to the workmen. “You will build a room here. D’accord?”

At last, free from whatever threats the président had made against them, they were ready to assent. The président nodded his head in approval, happy in the illusion that after the repair work was finished he and his 24 friends would be the first to receive brand-new houses. For now, it suited Intellect’s purposes to let him believe that.

“I’d like to have my confrontation with him later,” Parker said, “when I’ve created a political reality that he can’t stop without starting a minor revolution.”

The resistance had been broken, and everyone was coming forward, offering his house to be repaired.

“It turned out to be an authority problem,” Parker said. “The people just didn’t think they had the authority.”

Maybe that was all it was, the simple reality of political pressure. But it seemed for a moment that other, deeper hesitations were at work. The man who had insisted earlier that his grandmother had forbidden him to rebuild now informed Parker that she had changed her mind. It struck me that perhaps this grandmother was not necessarily flesh and blood but part of that larger family group called the fianakaviana, which included both the living and the dead. And perhaps she had been wary enough of the unusual beneficence of these strangers to think of them at first as fady.

As Parker gave final instructions to the workers, Cuny and I watched a toddler in a ratty diaper playing with a tin can on a pile of dirt. The little boy was thin, with a protruding stomach.

“He’s got a good case of the worms,” Cuny said. “His ribs are showing, so that means the worms are getting more of his food than he is. Probably by the time he’s four or five, he won’t have the strength to fight it. His chances of getting much older are pretty slim.”

No Place for Virgins

We were in the capital city of Antananarivo, in the restaurant of the Madagascar Hilton, where something billed as “A Texas Barbecue” was in progress. A waitress dressed as an Indian princess had handed us paper cowboy hats when we entered and then had shown us to a buffet table disguised as a covered wagon. There we assembled tacos from the available ingredients, which included crepes, ground zebu beef, barbecued cabbage, and mango chutney instead of hot sauce.

“Don’t you love being from Texas?” Cuny said, although he asked me to note that he refused to wear his cowboy hat.

Cuny planned to stay in Antananarivo off and on for another two weeks. The day he had left Mahajanga, Parker and Hardin had begun distributing the tôle, and Cuny felt that his presence in the capital would help ensure that the government’s interest in the program would not flag at this critical moment.

“This field is so open to innovation,” he said, growing reflective while a pianist in a derby pounded out a lusty version of that Texas classic, “Camptown Races.” “Anybody with good ideas can in a few months be years ahead of the relief agencies. When you have people like us who’ve been in the business for ten years—well, we’re light-years ahead. What we’re trying to do is push the state of the art. We want to go to the threshold—beyond the threshold.

“I always tell people that an organization that really knows a disaster and what happens afterward can be far more effective than a guerrilla operation. You want land reform? After an earthquake, land values plummet. Go in there and buy fifty acres of land, sell it, use some of the money to finance reconstruction programs, provide the rest of the land to poor people. Disasters are too important to be left to some of these amateur volunteer agencies. When you’ve got a national tragedy, by God, use it!”

Cuny’s grand vision for disaster relief involved developing an “agenda of research.” The emphasis of most relief agencies was still on the short-term emergency rather than on long-range planning. That SWAT-team approach was encouraged by the agency’s donors, who had a natural desire to see their dollars bring some sort of immediate results, and by the prevailing official notion that an emergency is something that lasts sixty days.

“The biggest obstacle is the program approach, where you have a certain amount of dollars, a certain number of people, a certain length of time, earmarked to deal with a disaster. We need to look at non-programs that will keep things moving, that will go on forever.”

Intellect, he said, plowed a significant amount of its profit into research that nobody else would fund. The company had been working with the University of Wisconsin to develop a comprehensive series of courses in disaster management, and Intellect’s Dallas office was filled with how-to manuals, many of them written by Cuny, on everything from the use of satellites in disasters to food distribution for famine victims.

Cuny had learned the power of manuals when he worked with an influx of refugees in a country that he preferred to leave nameless. The local government wanted to move the refugees to a camp just below a ridge that was controlled by the army from whom they had just fled.

“Everything about the site was wrong,” Cuny said. “It was located right in the middle of forty square kilometers of sand. There was no way you could support it logistically. You’d need about two hundred tanker trucks operating around the clock. And the army could fire down on the refugees from that ridge. I told the coordinator of the relief operation we were working for that we couldn’t let the government put them down there, that they were all going to be killed, if not by the enemy, then by disease or starvation. He said, ‘It’s out of my hands.’

“But I decided it wasn’t out of mine. The move had to stop, or all those people would be killed. So we decided to write a manual setting forth the policies and standards of the United Nations. We made it as official-sounding and specific as we could. For forty-eight hours we were sitting and revising these standards, and we put together this damn book that was this thick. We took it down to the government’s refugee officer. They were about to move all these refugees to the camp, and then we whipped out this book and said, ‘You can’t do that. That site doesn’t meet the UN standards for refugee camps as set forth in their manual.’ They said, ‘Oh. Well, we’d better inform the minister.’ After that the whole thing just died.”

Leaving our paper cowboy hats in the restaurant, we drifted outside to walk downtown. Antananarivo was Madagascar’s sole metropolis, a city of 625,000 built on the sheer eastern edge of the central plateau. It was a picturesque city in the daytime, dominated by the palace of the Merina monarchs. The Merinas were “the people of the plateau,” the Malagasy tribe that had once dominated the island and finally lost it to the French. Even the architecture of the palace was a testament to European dominance, as were the pastel stucco buildings huddled together on the slopes of the escarpment and the broad esplanade below, which was obscured on market days by a sea of white umbrellas.

Beneath the palace, in the center of town, was a small lake ringed by jacaranda trees. Nectar dripped from their lavender blossoms. The soil surrounding Antananarivo was as red as soil in Oklahoma, and the road from the airport was lined with market stalls and bungalows made of red brick. A vast quilt of rice ponds stretched out from the borders of the city, and the dry hills beyond it were fringed with eucalyptus and pine.

Within this pastoral setting there was hellish poverty. Beneath those jacaranda trees stood houses so squat and small and haphazard they might have been beaver dams. In a dark automobile tunnel filled with exhaust fumes, stunted and wizened children sat on the sidewalk, holding one palm upward and gripping an even younger sibling with their free arm. Antananarivo was the sort of place where you could climb a hill in a city park, being careful not to step in the human excrement left over from a camp that had been there the night before, and find an elegant French restaurant at the top. The poor of Antananarivo had been spared the cyclone, but they looked as if they had not been spared much else.

We passed a group of soldiers, teenagers in fatigues and worn-out tennis shoes casually toting AK-47’s. There were more of them in front of the presidential palace, and they tensed visibly as we walked by. These days, one heard, Didier Ratsiraka was nervous. The “socialist paradise under divine protection” he had once prophesied had manifestly not come to pass, and he saw enemies everywhere, from South African secret agents to martial arts enthusiasts (whose sport he had recently banned, touching off a riot that had come to be known as the Kung Fu Rebellion). Several years earlier, he had contended publicly that one of his enemies had hired a witch doctor to call down lightning on his head.

In Cuny’s years as a disaster consultant he had worked with a variety of governments. Not all of them were as hospitable as Madagascar, despite its shakiness, had proved to be.

“This is one of the dilemmas we have to work with,” Cuny said. “Anything you do that makes the government look good legitimizes the government. The truth is that there are very few governments in the developing world you want to encourage. A lot of these countries, if they knew the kind of stuff we were doing—having Kent and Ron out organizing in the communities to try and improve people’s lives—there’d be a backlash.

“What’s really needed in these parts of the world is something that guides people into development without stripping them of their traditions, that steers them between repressive socialism and communism on the one hand and on the other hand a rampant free-market economy that keeps them peasants.”

That was not an easy balance to achieve. Many of the people Intertect trained as carpenters in Guatemala, for instance, became targets of right-wing death squads.

“That’s another dilemma of relief operations,” he said. “We tend to create leaders who become targets. One of our best guys was taken out one night, mercilessly tortured, and then lynched in front of a model house.”

Disaster relief had rarely been a pure humanitarian enterprise. All too often it was manipulated for tactical advantage by the very governments that had caused the disaster in the first place. In Somalia in 1980, for instance, Intertect, along with some of the relief agencies that were operating there, was faced with an unsavory moral problem. After Somalia lost a border war to Ethiopia, thousands of Somalians who had been living in Ethiopia began to drift home. The Somalian government, which was still fighting a guerrilla war against Ethiopia, didn’t want to feed and house those people with money that could be used in the war effort. So even though they were living in an area that the Somalians said was part of their country, the government asked the United Nations to classify them as refugees.

“So what do you do?” Cuny continued. “If you don’t support them, they die. The UN decides to call them refugees, so they become refugees. If the relief agencies support them, the Somalian government would take money it normally would spend on them to fight the guerrilla war and create more refugees. We could have called Somalia’s bluff, but they would have outbluffed us and let them die.

“You go through a lot of moral torment in this business. As a friend of mine says, it’s no place for virgins. You’re always asking yourself what’s the least worst choice.

“The more satisfying work is natural disaster work. You can create the matrix for change. It’s a long, slow, tedious, backbreaking thing. But if you lay it solid, you can plant a seed, and next thing you know, you have a quiet revolution going.”

We passed a decrepit movie theater, which, according to the poster outside, was showing 7 Minutes pour Mourir, starring Paul Stevens and Betsey Bell. An old man had positioned himself on all fours in front of the ticket booth, and without moving, he stared into the dark, vacant lobby as if there were something inside that he was trying to understand. A boy of perhaps three walked by holding a baby that was no larger than the baby lemur I had seen wrapped around its mother’s torso in Mahajanga.

The streets were crowded in the Zoma market, down by the old French railroad station, but they were illuminated only by starlight. The picturesque colonial buildings on either side of the esplanade began to seem too picturesque, architectural frills that did nothing but mock the poverty surrounding them.

“Let’s go down here,” Cuny said, turning into a dark side street that was crowded with makeshift food stalls. The glow of candles and braziers was the only light. The homeless were taking apart some of the stalls and constructing shelters for the night on the side of the street.

“Monsieur! Monsieur!” cried a little boy as he came up to us. He was holding out his straw hat, begging.

Cuny knew no better than I how to deal with the boy. Awkwardly, he shooed him away.

“The kids who are begging are not the worst off,” he said. “The kids who need the assistance are the ones you have to go out and reach. You’re never going to see them. They’re never going to come to you.”

He walked on awhile in silence, then said, “The worst thing I can remember happening was one time when I was in Haiti. This woman came up to me and started asking something in Creole. I couldn’t figure out what she was saying, but I could tell she was trying to sell me something. Then she went inside for a minute and came back to show me what she wanted to sell. It was a six-week-old baby.

“Sometimes,” he said, “the only way you can cope with it is to just go home at night and cry.”

After Madagascar, Cuny was scheduled to spend three months in the Sudan, to advise the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees on the management of emergency operations for Ethiopian famine victims. There would, no doubt, be a few tearful nights there. I remembered that boy at Abattoir, the one Cuny predicted would not live beyond four or five; and under the gorgeous star-ridden sky of the Southern Hemisphere it was hard to shake the grim conviction that the world itself was a disaster and was never meant to be any other way.

But that despairing moment passed, and here was Fred Cuny, talking about hurricane straps again, and wondering whether Hardin and Parker had found a zebu to sacrifice to the sacred crocodiles of Lake Anivorano.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas