A year ago today, I stood outside the east side of the U.S. Capitol, with the Supreme Court building directly behind me, and watched as hundreds of insurrectionists climbed the Capitol steps and flooded inside the building. Today, I’m staring at a photograph I took of that moment, time-stamped 2:08 p.m. There’s an American flag flapping directly above the building’s Corinthian columns and beneath the overcast winter sky. At least a dozen more such flags are being held by members of the crowd on or near the staircase. They’re everywhere. I had not noticed those American flags at the time.

I failed to notice them because at that moment, it did not seem to me that I was in America anymore. The tableau of unrestrained mob rage—expressed in the vicious assaults on Capitol police officers I had witnessed from inside the building’s west terrace moments earlier—seemed more in keeping with what I’d expected to encounter on past overseas assignments in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, or Yemen. This was Washington, D.C., the nation’s capital, where I’d lived the past fifteen years. The moment was one of absolute dissociation. I had never felt so far from home.

Then again, the same was perhaps true for most of those around me. According to data tallied by the George Washington University Program on Extremism, 704 Americans have been charged by the federal government with crimes connected to the January 6 assault on the Capitol. Of those indicted, only four are D.C. residents. The remaining 700 came from 45 states across the U.S. The alleged rioters traveled from as far as Alaska and Hawaii.

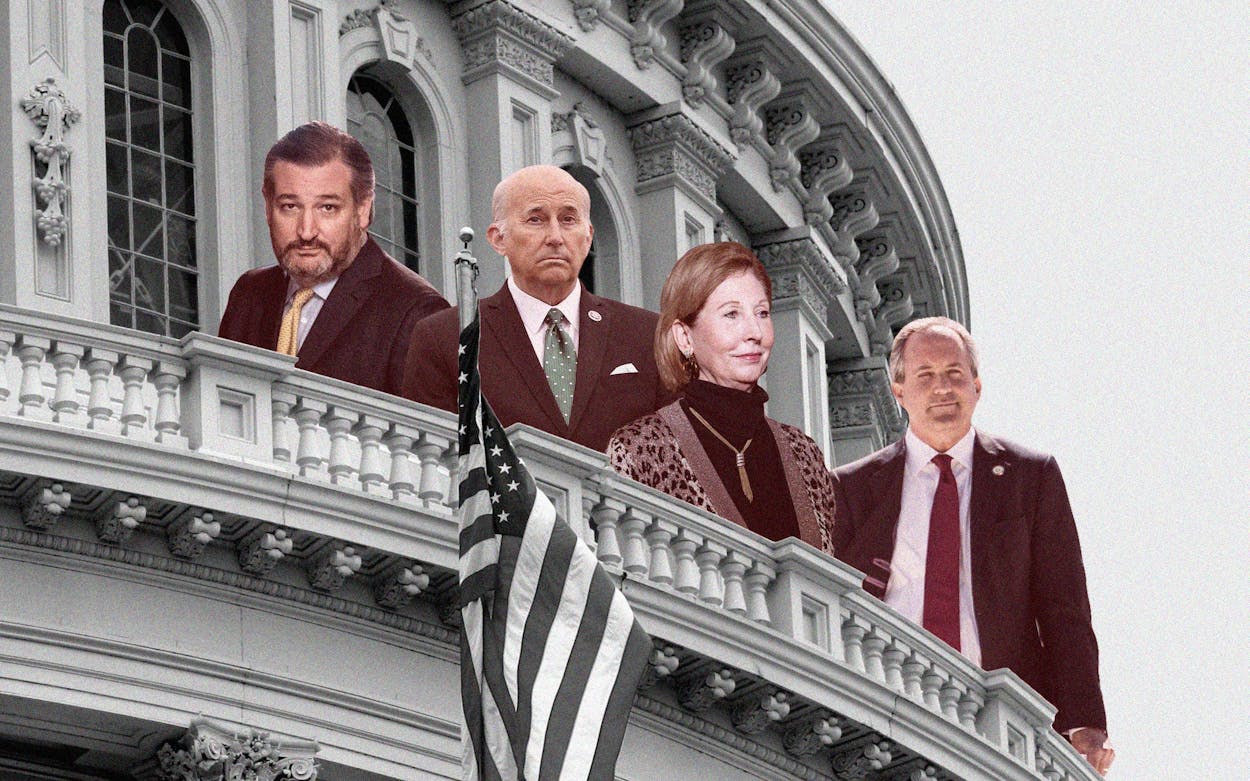

Let us turn our attention to the state that contributed more than any other to the events of January 6, 2021. By number of participants arrested, it’s Florida, which had 75 residents charged for their roles in the insurrection. Two states are tied for the second-highest number of indicted January 6 participants. Pennsylvania, whose Republican state senators President Donald Trump called to the White House as his team scrambled for ways to reverse the election results, had 63. As did Texas. But by the metric of which state most aided and abetted Trump’s efforts to overturn the election, Texas far surpasses Florida, Pennsylvania, and the field.

Within days after the final electoral tally on November 7, a Dallas-based appellate litigator named Sidney Powell began the process of cranking out what she referred to as Kraken lawsuits—named for a mythical Scandinavian sea monster—in the four contested states of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Two of Powell’s election-fraud “experts” were also Texans. One, a retired Army colonel and Dripping Springs–based distillery owner, Phil Waldron, would claim to credulous Trump supporters that voting machine algorithms had been rigged in Joe Biden’s favor. The other Kraken foot soldier hailed from the Fort Worth suburbs: Seth Keshel, a lanky former military intelligence officer now selling traffic-light software—until the day after the election, when Keshel christened himself an authority on election data anomalies and thereupon offered his services to Sidney Powell.

By December, as it became clear that many Republicans were receptive to hallucinatory Kraken depictions of an election undone by a conspiracy of Democrats, Republicans in Name Only (or RINOs), voting machine corporatists, and foreign actors, Texas’s leading GOP lawmakers decided to get on board. On December 8, state attorney general and Lawyers for Trump cochair Ken Paxton filed a lawsuit seeking to overturn the election results in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Georgia. (Disclosure: my cousin, former Galveston mayor Joe Jaworski, a Democrat, is running for state attorney general.) Governor Greg Abbott lent his support to Paxton’s effort, saying that throwing out all the votes in the four battleground states would somehow provide “certainty and clarity about the entire election process.” Nearly two thirds of Republicans in the U.S. House eagerly put their weight behind the Paxton lawsuit.

When the Supreme Court predictably ruled that Texas lacked the standing to pursue a suit over how other states conducted their electoral affairs, yet another Texan stepped into the fray: Louie Gohmert, the attention-craving congressman from Tyler. Gohmert brought his own lawsuit, targeting, of all people, Mike Pence, demanding that the vice president discard the electoral college votes and award the election to Trump—a gambit that Pence opposed. A federal judge in Texas dismissed Gohmert’s complaint.

With all legal remedies exhausted, members of the U.S. Senate filed into the House chamber at one in the afternoon of January 6, 2021, to formalize the electoral tally. I stood in the marble hallway about eight feet from the procession. The junior senator from Texas, Ted Cruz, wore a natty blue suit and lavender tie. I snapped a picture of him bending the ear of Connecticut Democrat Chris Murphy, who stared straight ahead, no doubt aware of the rumors that Cruz intended to make history exactly twelve minutes hence.

When the vice president asked whether Arizona congressman Paul Gosar’s challenge to the election results in his state was signed on to by any member of the Senate, Cruz answered, “It is.” Thus did Cruz become the first U.S. senator ever to join a House member in objecting to a slate of state electors in a presidential election. Minutes later, the senators strolled eastward through the Capitol rotunda and back to their chamber to debate the Arizona certification matter.

By this time, President Trump had concluded his speech on the Ellipse—saying to tens of thousands of supporters, “So let’s walk down Pennsylvania Avenue.” Trump, famously averse to physical risk, did not actually do so. Nor did one of the earlier speakers, Ken Paxton—though in his brief remarks, the state attorney general offered up a role model for the fight to overturn the 2020 presidential election. Unlike other states, Paxton declared, “We kept fighting in Texas.” He added, “We will not quit fighting. We’re Texans, we’re Americans, and the fight will go on.”

And so, moments later, it did.

The 63 alleged rioters from the Lone Star State came in all shapes and sizes. They included a Midland jailer, a Houston Police Department officer, two retired Marines, a winemaker from Eddy, a coffee roasting entrepreneur from Odessa, a San Antonio mortgage branch manager, and Infowars host Owen Shroyer, also from San Antonio. Among them were several couples, including Mark and Jalise Middleton of Forestburg, both of whom were later detectable in body camera footage fighting viciously with the police at the lower west terrace “to get to the Capital [sic] to send them bastards a clear message that this won’t be tolerated,” as Jalise posted on her Facebook account. Two father-son pairs from San Antonio and Blanco made their way inside the Capitol, as did an entire family of six, the Munns from the Panhandle town of Borger, only one of whom was not indicted, as that child was a minor.

The Munns, like numerous other Texans, tipped off their whereabouts that day by proudly memorializing their place in history on social media. This was also the case with Nick DeCarlo, who wore a shirt that read “MT media,” or “murder the media,” and posed for a photograph with his thumbs up next to a Capitol door with the same message etched into it. A few Texans participated in the storming of the Capitol as a kind of patriotic frolic—including Jenna Ryan, the Frisco realtor who flew in on a private plane, and later provided a smug explanation for why she would never spend a day behind bars: “blonde hair white skin.” (As of this writing, she’s serving a sixty-day sentence at the minimum-security prison camp in Bryan.)

For others, however, the insurrection constituted a personal apogee. “Proudest day of my life,” wrote Sean David Watson of Alpine, adding “I f—ed s— up.” “That was the first time I felt invincible,” wrote Stacy Hager of Gatesville after scaling the walls of the Capitol while carrying a Texas flag. Taking umbrage at claims from some on the right that the riot had been instigated by Antifa, Richardson-based Garret Miller wrote back, “Nah we stormed it,” while Ryan Nichols of Longview wrote that “every single person who believes that narrative have [sic] been DUPED AGAIN.”

And though some remained insistent that the episode had been a peaceful one, other Texas rioters were captured in video footage using whatever weapons were at their disposal: pepper spray, stolen batons, a skateboard, a crutch, a tabletop. At least one—Guy Reffitt, from the North Texas town of Wylie, a member of the extremist militia group called the Texas Freedom Force—allegedly brought guns with him to Washington.

Meanwhile, several other Texans now under federal indictment had made clear on social media that their intentions were not pacifist. Here, for example, is retired Air Force officer Larry Brock: “men with guns need to shoot there [sic] way in.”

From the aforementioned Ryan Nichols: “Pence better do the right thing, or we’re going to MAKE you do the right thing.”

From Troy Smocks of Dallas: “It wasn’t the building we wanted . . . it was them!”

Garret Miller again: “Assassinate AOC.”

Should we be surprised? Texas’s singularity—symbolized by the lone star on its flag—has long manifested itself in scornfulness toward the very federal government that rescued the fledgling republic from bankruptcy in 1845. Texans reflexively maintain that this distrust is a healthy thing. Never mind that the state has historically enjoyed considerable influence in Washington—including, in my lifetime, three U.S. presidents, two House speakers, one Senate majority leader, numerous committee chairs, and a deep bench of K Street lobbyists. Never mind, as well, that Texans have never refused the federal government’s largesse. (Last year, the state received a $1.20 return from the U.S. government for every dollar it was taxed, more than the blue states of California, Massachusetts, and New York.)

The problem with distrust is that it’s an unsustainable human condition—a vacuum waiting to be filled by a satisfying narrative; a belief. Populist demagogues have long known this. So have Vladimir Putin and his GRU intelligence service. Based on the available evidence, it appears that the Texans who descended on the Capitol with their fellow insurrectionists on January 6 were not exactly fevered with prudent skepticism. What instead animated them was a belief in Donald Trump that never swerved, even as his lies were revealed as baseless, including by more than a dozen Republican appointees to the federal courts.

One year later, according to a national poll conducted by CBS, self-identified Republicans maintain a not-altogether-coherent view of the attack on the Capitol. Among respondents, 57 percent believe that those who swarmed the Capitol were “defending freedom,” while 41 percent believe that most of the rioters belonged to “left-leaning groups.” Situational truth is necessarily a psychic muddle. Distrust, on the other hand, remains a dependable opioid. Today, Texas GOP leaders such as Ted Cruz and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick winkingly ennoble the idea of secession, while Governor Abbott, at Trump’s command, has gamely signed on to the kabuki rite of randomly auditing Texas counties for evidence of election theft—evidence that never seems to turn up.

It’s hard to know where this all ends. If our democracy does somehow overcome its dystopian free fall, belief may be what gets us there. A great Texan showed us the way not so long ago, in 1974, when Barbara Jordan, a Black congresswoman from Houston’s Fifth Ward, explained her decision to impeach President Richard Nixon. It was rooted, she said, in faith—not in a politician or a movement, but in her country’s foundational document, written by white men, including slaveholders who would have thought her unworthy of the office she now held. “My faith in the Constitution,” Jordan said, emphatically and unforgettably, “is whole. It is complete. It is total.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ken Paxton

- Donald Trump