Nine o’clock in the evening on a Saturday night is a curious time for a governor to announce a legislative initiative, but that was when California governor Gavin Newsom posted last weekend about his new plan to regulate certain guns in his state. “We will work to create the ability for private citizens to sue anyone who manufactures, distributes, or sells an assault weapon or ghost gun kit or parts in CA,” Newsom’s office tweeted.

Newsom’s plan—to allow private individuals to file lawsuits against one another for engaging in constitutionally protected behavior—might seem like a stretch, but he has some reason to believe it’s feasible. The day before, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed Texas’s Senate Bill 8, the six-week abortion ban passed this summer, to remain in effect despite similar constitutional concerns.

In announcing the proposal, Newsom made clear that the law he’s supporting would function similarly to SB 8, creating what the courts call “standing” for anyone to sue anyone else on the grounds that the defendant had manufactured, distributed, or sold an “assault weapon” or “ghost gun kit”—an untraceable firearm that can be assembled at home. Newsom’s proposal, like the Texas abortion measure, calls for a minimum award of $10,000 if the courts find the defendant violated the law. Newsom’s timing in making the announcement, and its direct references to SB 8, gave the whole thing an air of trolling, a tit-for-tat bit of “let’s see how you like it when the constitutional rights you value are at risk” aimed at Texas, abortion rights opponents, and the five Supreme Court conservatives who kept SB 8 in place.

The Texas law takes a novel approach to judicial review. The state doesn’t enforce SB 8—rather, it leaves that to any U.S. citizen who chooses to file a lawsuit against anyone who “aids or abets” an abortion more than about six weeks after conception (a period during which many women don’t yet know they’re pregnant). If the state isn’t the entity enforcing the law, Texas officials argue, then plaintiffs such as the abortion providers whose services are curtailed by the law can’t name a state official to sue, which effectively means that they can’t challenge the constitutionality of the law.

Gun rights advocates, among others, have worried that the Texas law is too clever by half, and might create a slippery slope leading to some unintended consequences. The Firearms Policy Coalition, a California-based organization that opposes gun regulations, filed a “friend of the court” brief lending its support to the lawsuit filed by Texas abortion providers, writing that the “delegation of enforcement to private litigants could just as easily be used by other States to restrict First and Second Amendment rights or, indeed, virtually any settled or debated constitutional right.”

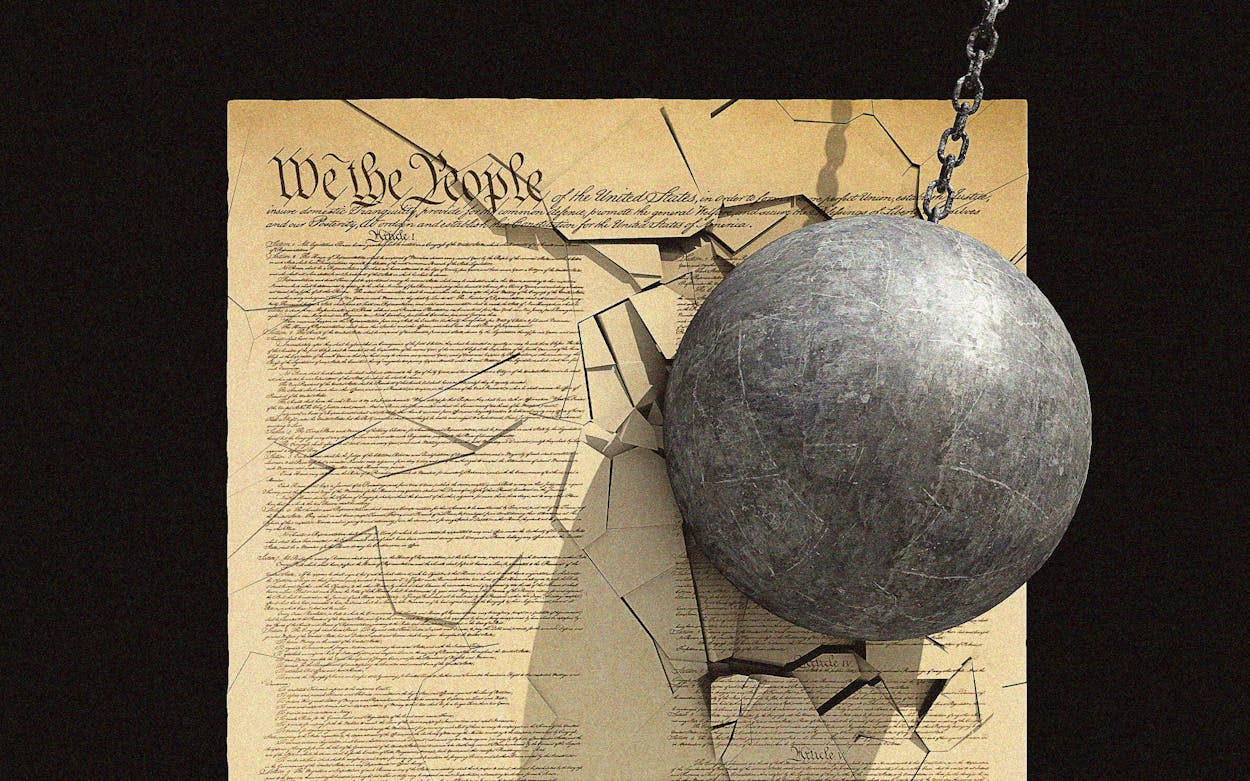

The risk here is substantial—whether for enumerated rights that explicitly appear in the Constitution, such as the right to bear arms, or for unenumerated rights such as abortion that decades of court precedent have clearly established. (The list of unenumerated rights that Americans take for granted is long. It includes the right for consenting adults to do what they like in their bedrooms, the right to send children to private school, and the right to travel between states.) For generations, Americans could assume that if a state tried to pass a law that infringed upon a constitutionally guaranteed right, the Supreme Court would strike down that law as unconstitutional.

The structure of SB 8 is cleverly built specifically to avoid that sort of review, and the court’s ruling on it more or less says that it worked: The ruling isn’t about the merits of abortion as an unenumerated right and how that might compare with, say, the Second Amendment. It’s a technical ruling that says that even if SB 8 violates the Constitution, it can’t be reviewed by the courts because there isn’t a valid defendant to name in a lawsuit. (The ruling does allow a narrow path for lawsuits against certain licensing bodies, such as the Texas Board of Nursing and the Texas Board of Pharmacy, but even if the plaintiffs in those cases prevail, a ruling is unlikely to affect the $10,000 minimum fine, which is the part of the bill that can drive a defendant into bankruptcy.)

It isn’t hard to come up with a long list of settled rights that some state legislature somewhere could decide that it doesn’t like and then introduce a similar bounty schemes for. The Second Amendment might guarantee the right to bear arms, but if California creates a law under which anyone who sells an AR-15 is subject to a $10,000 lawsuit by a random neighbor, and the court applies its ruling consistently, gun rights advocates won’t have anyone to sue to test the law. They might be able to prevail in court after they’ve been sued—and such a law could be struck down—but anyone who writes down a few license plate numbers from the parking lot of a gun show could still make life miserable for all in attendance in the meantime.

There’s no reason to believe the use of vigilante-enforcement tactics would be limited to abortion and guns, either. Could, say, Alabama pass a law that would allow any citizen to sue another individual who uttered the Lord’s name in vain, and leave the Supreme Court’s hands tied as to whether it can intervene? There’s a general consensus among legal scholars that such a law would be unlikely to survive on its merits—the First Amendment is clear about both freedom of speech and “no law respecting an establishment of religion”—but defending a case on its merits still takes time, money, energy, and resources, which is why pre-enforcement review of unconstitutional laws exists in the first place.

What Texas did—and what the Supreme Court affirmed in its ruling—has big implications, in other words, for the constitutional order we’ve grown accustomed to. “Pulling a thread on democracy is dangerous, and that’s what Texas has done,” said Susan Liebell, a political scientist at Saint Joseph’s University whose work focuses on gun rights, law, and democratic theory. “We all, no matter what side of the political spectrum we’re on, need to be aware that we’re slipping in our definition of democracy. Newsom is pulling on that thread too, and it’s dangerous, even though I understand why he’s doing it.”

Nonetheless, many liberals reacted to his tweet announcing the legislative troll job as though it were a video of the governor rescuing a drowning child. It’s easy enough to understand why abortion rights supporters who oppose the proliferation of assault weapons might feel a certain level of visceral satisfaction about Newsom’s move—what’s good for the goose is good for the gander, and all of that—but upon reflection, wouldn’t it be better to have a functioning federal constitution instead?

The Texas law’s future is still murky. On December 9, a state court ruled that the private enforcement mechanism violates the separation of powers outlined in the Texas constitution. That ruling doesn’t settle the issue, as the appeals process is ongoing, but it suggests that, even if the law won’t be reviewed by federal courts, Texas’s courts could intervene. Would the same thing happen in California? Bryan Hughes, the Texas state senator who introduced SB 8, told the Texas Tribune that he’s not concerned that it would get that far. He thinks that a California copycat law would meet a different outcome than SB 8. “If California takes that route, they’ll find that California gun owners will violate the law knowing that they’ll be sued and knowing that the Supreme Court has their back because the right to keep and bear arms is clearly in the Constitution, and the courts have clearly and consistently upheld it,” he said.

There’s nothing in the SCOTUS ruling itself, however, that indicates why that would be the case. The courts have also clearly and consistently upheld that the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees a right to an abortion. But Hughes is not alone in thinking that the Supreme Court might apply a different standard to abortion than it would to guns. “If this were a gun case, there’s no way that [Neil] Gorsuch would have written this opinion,” Liebell told me. She thinks that today’s U.S. Supreme Court is largely a partisan body whose conservative members were selected because of their willingness to restrict abortion, and ruled the way they did to advance the outcome they sought. “This is about politics, and about what people believed prior to being on the court,” she said.

Erik Jaffe, the lawyer who authored the amicus brief on behalf of the Firearms Policy Coalition, isn’t so sure about that. He believes that if Newsom had gotten to the Supreme Court first with a “bounty” law targeting guns, the court would have ruled the same way it did in the abortion case. He imagines a future in which the U.S. Supreme Court is less involved in guaranteeing constitutional rights than it has been since before the Warren court of the sixties—a prospect he thinks could ultimately be healthy for democracy. For the past sixty years, he said, we’ve been “living in a country where the Supreme Court says, ‘None of you folks worry your little head about the Constitution, we’ll tell you what it means,’” he told me. “It’s comfortable to know the Supreme Court’s got your back, but it let us basically put our guard down and let us ignore the fact that we’re electing pieces of s— who don’t care about the Constitution, and who have no notion that they’re bound by it.”

Jaffe recognizes that a gun-rights organization and Texas abortion providers are “odd bedfellows,” as he puts it, but he’s hopeful that perhaps Congress might find some odd bedfellows of its own, and pass laws that do what the Supreme Court has decided it doesn’t have the power to do: put a stop to “bounty”-style laws such as SB 8. “It seems fanciful that we could get Congress to agree,” he admitted. “But if you get the pro-choice people and the pro-gun people on the same side of a fight up in Congress and say ‘Texas is screwing them, California is screwing us, and this whole shebang is ridiculous,’ you never know what you could get out of Congress.”

Ultimately, it’s clear from the Supreme Court ruling on SB 8 that we are entering uncharted territory when it comes to how the constitutional order is maintained and protected. Liebell sees two potential scenarios for the court, if California lawmakers follow through on forcing it to apply the same argument toward a gun law as it did toward abortion. “They have two bad options,” Liebell said. “One is to be consistent, which would help destroy judicial review. The other is to reveal themselves as hypocrites, and potentially destroy the respect that Americans have for the court .”

- More About:

- Texas Lege

- Supreme Court

- Abortion