For much of our state’s history, the Texas Rangers earned their reputation as frontier lawmen. They covered vast territory on horseback and often defended settlers from outlaws, even as some Rangers unloaded their six-shooters indiscriminately on Mexicans and Comanche. By the mid-twentieth century, though, no one could confuse Texas for the frontier, and the Rangers, lacking a clear purpose, entered a transition period. Governors put them on riot control and had them investigate narcotics cases and engage in strikebreaking. By the seventies, the Rangers had transitioned again, becoming Texas’s top detectives, highly regarded for their skills as interrogators.

“They’re always trying to stay ahead of everybody else,” said Joe Davis, who joined the Rangers in 1969 and retired in 1993. He learned that a polygraph test could be a useful tool, even though experts knew that the tests are often unreliable and are inadmissible in Texas courts. During his first murder case, in 1969, Davis’s main suspect agreed to take a polygraph. When Davis told him he’d “flunked,” the man gave in. “If they’re guilty, sometimes they’ll go ahead and confess, knowing that you know that they did it,” Davis explained.

Today, the Texas Rangers are frequently called in by law enforcement officials to break down suspects no one else can crack. Over the past fifty years, they’ve brought to justice hundreds of criminals and have solved at least thirty cold cases since 2015, according to the Marshall Project. One Ranger, James Holland, persuaded a man named Samuel Little to confess to 93 murders. Holland has been accused of extracting a false confession in another instance, but more than sixty of the murders to which Little confessed have been attributed to him through other evidence.

Former Rangers chief Tony Leal said the legend is part of what makes the officers such effective interrogators. “When [suspects] see a Ranger walk in the room, they begin to panic,” Leal told me. But sometimes the Rangers’ mystique may hold too much sway over witnesses and juries.

In 1992 police arrested a Brenham man, Anthony Graves, on suspicion of killing several victims. Four Rangers spent hours interrogating Graves, who repeatedly told them that he knew nothing about the crime. Eventually, he agreed to take a polygraph. The Rangers told Graves he had failed the test—which was administered after he had been in custody for more than seven hours—and then pushed him to confess, to no avail.

There was no physical evidence tying Graves to the crime, so the investigators used hypnosis—a technique widely regarded as unreliable—on a potential witness, who then picked Graves out of a lineup. Graves was prosecuted and sentenced to death. He spent eighteen years behind bars before he was released, having been completely exonerated. The Rangers who investigated him “are no different than a bunch of corrupt cops on the local beat,” Graves told Texas Monthly. “I experienced it firsthand.”

In a 2005 case, a Ranger almost certainly elicited false testimony from four East Texas children who alleged they had been sexually abused by a group of adults, seven of whom spent years behind bars before six were released after agreeing to plead guilty to a lesser charge (one died in prison while appealing his case). Melissa Lucio, who is on death row in Texas, says that a Ranger coerced an incriminating statement that helped lead to what many students of the case believe is a wrongful conviction for her daughter’s murder. It’s not just the Samuel Littles of the world who sometimes get ensnared by members of the legendary force.

To be sure, many Rangers remain the elite officers they are widely regarded to be. But in at least a handful of high-profile cases, the organization’s reputation has been undermined. Perhaps, critics say, the organization is due for another transition.

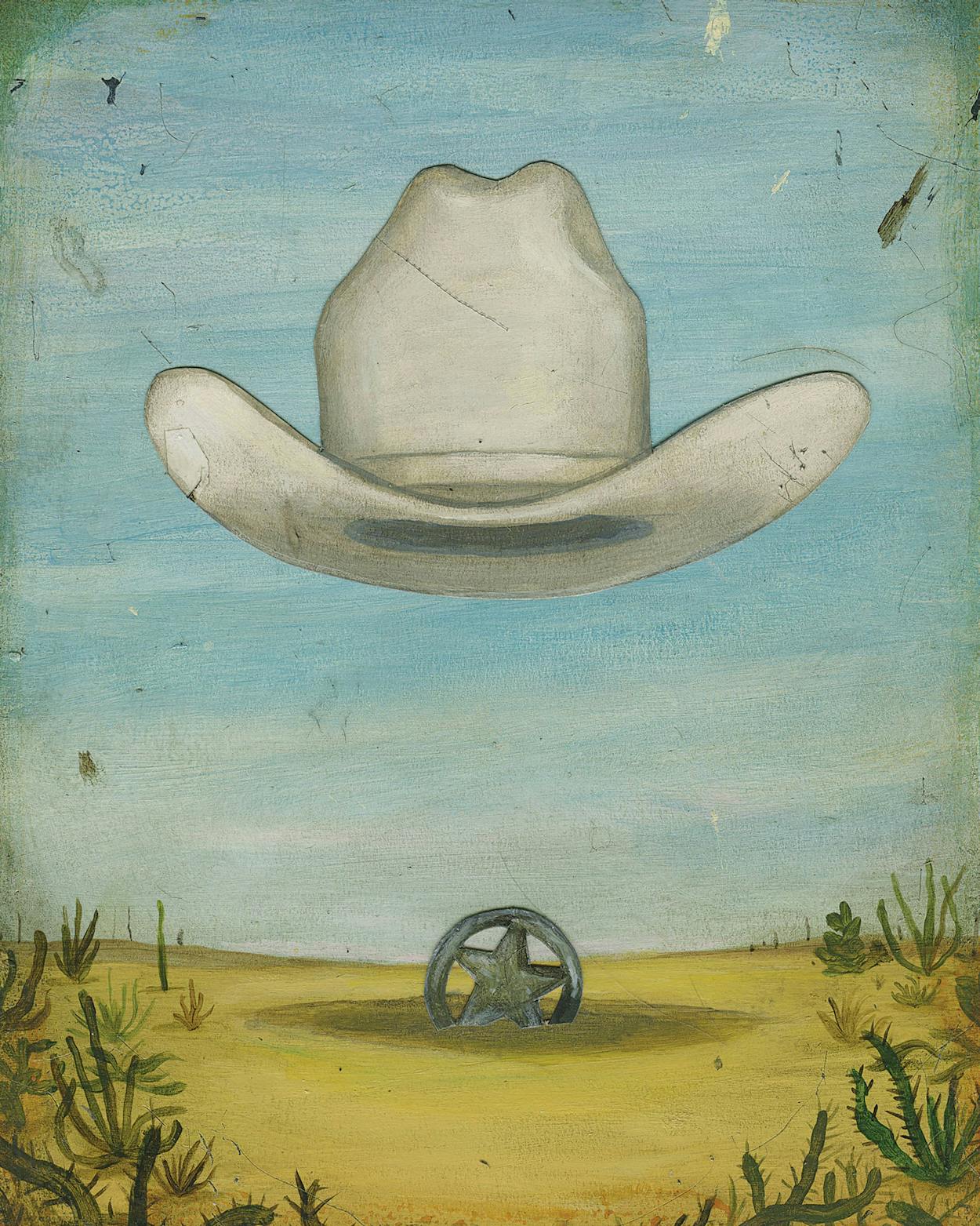

This piece draws on reporting done for Texas Monthly’s podcast White Hats, which explores the Texas Rangers’ legacy on the occasion of the agency’s 200th anniversary.

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Ranger Danger.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History