This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On the night before he was murdered, Lee Chagra returned home to El Paso flushed with the euphoria a gambler feels when he believes his luck is changing. Lee had been in Tucson trying a case for most of the past two weeks, and when the Friday night plane began its approach over the Upper Valley and through the Pass, he caught a glimpse of the lighted Christmas star on the slopes of Mount Franklin. The verdict in the Tucson trial had been sublime: in a highly publicized, multicount bank fraud indictment, Lee had walked his man on every count. It was his most important victory in months—and his most profitable. It was three days before Christmas, 1978.

All things considered, 1978 had probably been the worst year of Lee Chagra’s life. Worse than 1973, the year the federal government indicted him on a trumped-up marijuana trafficking charge in Nashville and nearly destroyed his law practice. Worse even then the chain reaction of disasters in 1977: the crash of one of his brother Jimmy’s drug smuggling planes in Colombia, Jimmy’s botched foray to rescue the pilot, Lee’s frantic scramble to rescue Jimmy, his running courtroom battle with federal prosecutor James Kerr and Judge John Wood. This year, 1978, had been a year of galloping paranoia. Lee had always lived his life on the edge of respectability, goading the El Paso establishment by defending hardened criminals, consorting with known drug smugglers, and cultivating his image as the Black Striker. Through it all, he had somehow clung to the central fact in his life: Lee Chagra was a topflight criminal attorney.

But now the years of fast living were catching up. His practice had foundered, he had run up huge gambling debts, his life was peopled with shysters and thugs; and if the truth was known, Lee himself had become little more than a highly paid functionary in Jimmy’s fluctuating gang of smugglers.

What’s more, Kerr and Wood and the entire apparatus of the federal government were breathing down his neck. They were making a career, or at least a crusade, of trying to prove that Lee Chagra, master criminal lawyer, was in fact master criminal.

For months Lee had been unable to shake the premonition that something wild and uncontrollable had broken loose. The madness seemed to peak in November, when two men in a van sprayed Kerr’s car with buckshot and .30-caliber bullets. Federal agents turned up at Lee’s office the next morning to confiscate his gun collection and question him about the unsuccessful assassination attempt.

On the plane from Tucson, Lee must have reflected on the paradox of his life. He sat next to a lawyer who worked for one of El Paso’s established firms in one of the high-rise glass towers that dominate the downtown district. The lawyer mentioned that he sometimes looked down at the office complex that Lee was remodeling and experienced pangs of envy. “You’ve got everything I always dreamed of having,” the lawyer said. Lee laughed with pride. The other lawyer couldn’t appreciate the irony, but until that moment, Lee had always envied him. The new office was a show of faith, or at least tenacity, and it made Lee feel good to know that someone else appreciated it. His staff had completed the move while he was in Tucson, and in the morning he would officially take possession: it would be his first day there and, as fate decreed, his last.

Jo Annie, Lee’s boyhood sweetheart and the wife who had seen him through law school and nineteen years of an emotionally charged marriage, met him at the airport. Two of their five children were with her. They had a surprise for Lee—a new Lincoln limousine with a portable bar, a TV, a stereo, and even a secret compartment to conceal his guns and playing cards. The perfect vehicle for the imperfect time. The family had a late dinner. Lee couldn’t stop talking about Tucson. It had been months since anyone had seen him so animated.

Sometime in the middle of the night, after everyone else was asleep, Lee changed clothes and drove to his new office. He let himself in with a specially made key and walked upstairs. He unlocked the door to his private bath. The money was in the canvas tennis bag under the sink. There was a steel floor safe sunk into five feet of concrete, but like the other safes, it hadn’t yet been completely installed. Lee counted out $75,000, slipped it into his coat pocket, and headed for his clandestine appointment.

As he pulled off the exit ramp above a truck stop on IH 10, Lee could see the Indian’s car parked in the shadows behind some eighteen-wheelers that idled in the predawn chill. The Indian brushed a strand of limp hair over his bald spot as he walked toward Lee’s car. The Indian wasn’t a man most folks would care to meet in the dark—there was a .22 pistol under his stained leather jacket, and his face looked like forty miles of bad highway. But Lee trusted him. The Indian worked as a collector for several Las Vegas casinos. Lee joked as he gave the Indian the $75,000, and the Indian mumbled and studied his boots. That was it, the last of the half-million the Black Striker had blown in Vegas the year before.

“What’s It All For?”

The next morning, a Saturday, was one of those perfect December days in El Paso when the desert air is so crisp you can hear it and the mountains loom out of the blue shadows and change colors before your eyes. Loaves of Syrian bread were baking in the kitchen. From a radio in another part of the house, Sinatra was singing about doing it his way. Lee’s morning coffee was perfect, and the cocaine was first-rate.

Lee had showered and was standing in front of the bathroom mirror in his shorts when his brother Jimmy’s ex-wife, Vivian, arrived. He called her into the bedroom. Vivian did her best to smile. She knew that Lee had just come through many weeks of hard times and she hated asking for money, but Jimmy was months behind in support payments. She had come to count on Lee—although she suspected that the money Lee gave her came from Jimmy anyway. And she suspected that some of the money that was paying off Lee’s elaborate new offices and his gambling debts came from Jimmy. But she wasn’t about to inquire; nothing brought Lee down faster than the slightest hint that he might somehow be beholden to Jimmy, even temporarily.

Vivian felt Jo Annie’s dark eyes following her into the bedroom. Whatever Jo Annie was thinking, she wouldn’t say anything. All of Lee’s personal affairs, especially those with women, were conducted behind closed doors. Vivian remembered the previous Saturday at his office; she’d heard murmurs from the staff as she followed him upstairs. Everyone had assumed they’d made love—Lee made a point of keeping her in his office long enough, then he flushed the toilet and gave her the money. The staff knew the ritual, but no one knew for sure what went on behind the closed door. That’s the way Lee wanted it.

Lee was preoccupied this morning. He hardly seemed aware she was in the room. He looked smaller than life as he stood there, facing the dresser, looking at the picture of his father and seeing his own reflection. Dad had been gone for eight years. Lee held the picture so it caught the light. “What’s it all for?” he said out loud, and Vivian could see the tears in his eyes and hear the catch in his voice. “He was up and down all his life . . . struggling. Just barely making it. Up and then down.” Vivian said she didn’t know. She had put the same question to herself. For six years now she’d been divorced from Jimmy and nothing much had changed. All she’d ever had was a future somewhat less than promising. Jimmy had given her a couple of kids and a lasting pain in the ass. There was a line from The Picture of Dorian Gray that she liked to paraphrase: “I hope that when I die and go to hell, they deduct those four years I spent with Jimmy Chagra.” She almost said it now, but the suffering in Lee’s eyes cut her off.

“I’m sick and tired of being the fall guy,” Lee said, and Vivian knew that he was talking about Jimmy. She didn’t know the details, but she had heard that Jimmy and his new wife, Liz, were living it up in Vegas. So Jimmy’s smuggling operation must be thriving as Lee’s law practice crumbled. Lee was down and Jimmy was up. And it was killing Lee.

“Maybe it will get better,” Vivian said. Lee kissed her and slipped her the money.

By the time Lee finished dressing, Jo Annie had breakfast ready—freshly baked Syrian bread, butter, and a variety of fruit preserves. While Lee ate, Jo Annie puttered with the Christmas decorations. If she realized how pressed he had been for money in recent months, she didn’t show it. Jo Annie’s own family, the Abrahams, had considerable wealth, and she continued to collect antiques and preserve an extravagant lifestyle. She had bought the Lincoln limo because she wanted to give her husband “something crazy after all these years.”

This morning Jo Annie had another surprise, a block of tickets to the afternoon’s Sun Bowl football game between Texas and Maryland. Lee had $15,000 riding on the game. He seemed pleased with the gesture but told her there was some work he needed to do at the office. He would try to join the family by half-time. That was when Jo Annie remembered the telephone call.

“A man named David Long phoned before you woke up,” she told him. “Something about a will, about some large estate in California? He needs you to look it over before he mails it back.”

“David Long?” Lee said. He didn’t appear to recognize the name.

A Little Healthy Corruption

If it was a crime to love the fast lane, Lee Chagra was guilty. He had an affinity for cards and dice, for dope dealers and shady politicians, for cripples and nightclub singers, for dabblers in the black market and exponents of the quick buck. They were all scammers, everyone he knew or cared about. He would lend a stranger his last $100, knowing he was kissing it good-bye. In his time, Lee had invested in a racehorse that ended up as dog meat, a pro golfer who never made the cut, a combination lock that served to secure nothing more than a long, bitter lawsuit, and a caper to corner the Colombian coffee bean market. His dream was to stash away $20 million, all taxes paid.

Lee was a baffling tangle of contradictions. He was a fanatic about his family: he lavished gifts on his wife, his children, his mother, his sister. Yet he could risk the family’s last penny on a roll of the dice. He called himself a pacifist, and yet he was comfortable around violence. He could be shamelessly sentimental and gentle as a whisper, and yet there was a macho fury inside that could make him turn on those closest to him. He referred to all of his male friends as “brother,” and yet there was a time when he couldn’t keep his hands off his real brother’s wives and girlfriends. “Gambling and women,” said Lee’s old friend and fellow lawyer Clark Hughes. “They were like a sickness with him.”

Lee also loved El Paso and had never thought of living anywhere else. He loved the streets and the people who plied them—whores, gamblers, smugglers, cops. El Paso and Juárez have always floated on a little healthy corruption. Crimes against persons are treated with extreme gravity, but crimes against the economy are treated with a wink and a smile. Traditionally, gambling and smuggling are on a par with fixing parking tickets and hiring illegal aliens. A ton of marijuana is no better or worse than a ton of quicksilver. It is estimated that one out of every five households in these two communities of one million is supported by some type of illegal activity. A few years ago, the director of El Paso customs acknowledged: “If we stopped all smuggling activity right now, the economies of two cities would fall flat on their faces.”

Millions of dollars’ worth of goods are smuggled daily across the three main bridges connecting Juárez and El Paso. Drugs are currently in fashion, but over the years whiskey, cigarettes, perfume, Swiss watches, silver, kitchenware, and of course, laborers have been staples in the trade. Fayuqueros (smugglers) from Mexico usually make two trips a week across the border, carrying about 250,000 pesos ($10,000) worth of goods each way. When the items are small, such as bottles of American perfume or jewelry, the fayuqueros hire old women called chiveras (shepherds), who actually carry the merchandise across the bridge and as far as Chihuahua City, 236 miles into the interior. The chiveras are paid $45 to $65, depending on the size and value of the haul; out of that money they are expected to bribe the various Mexican customs officials, who survive on bribes. “These people used to steal,” a Mexican policeman told the Associated Press recently, “but there is more money in contraband. Before, they ate beans and a little meat. Now they eat three meals a day and imported cheese. It’s good business for everybody.”

Of course, not all the authorities are so blasé. El Paso’s legions of smugglers—drug smugglers in particular—manage to get themselves arrested often enough to keep law practices like Lee Chagra’s busy and profitable. It was fitting in a way that Lee should end up championing the drug dealers’ rights; his brother Jimmy was destined to join their ranks.

The Chagras were fiercely proud people, a handsome, hardy, beguiling line of Lebanese merchants and vendors who migrated near the turn of the century to Mexico and then to El Paso. The family name was originally Busha’ada, but Lee’s grandfather mexicanized it during the revolution. The old man, who was a dead ringer for Pancho Villa, was imprisoned and almost shot before he and his family could escape across the border into El Paso.

Lee was the first college graduate in his family, and the first professional. He worked his way through the University of Texas law school, graduating fourth in his class in 1962. Lee Chagra was special, and he went out of his way to prove it: student court, law review, Order of the Coif. Some in the legal community thought he was too special, too outspoken. A major law firm that always invited the top six UT law graduates to a spring gala invited only five in 1962. Some speculated that they omitted Lee Chagra because he was from El Paso and had a Spanish surname. More likely it was because Lee, as chief justice of the student court, had spoken out against segregated dorms and football teams. When Lee was murdered sixteen years later, Charles Alan Wright, one of the country’s leading authorities on constitutional law, called him “one of the few students who stand out in my memory.”

There was never any doubt that when Lee passed the state bar exam he would join Jo Annie’s brother, Sib Abraham, who had finished law school the previous year and had already set up his practice in El Paso. In a few years Abraham and Chagra had the leading anti-establishment law firm in the city. They volunteered for every hard-core criminal case that came along: murder, rape, robbery, burglary. Sib remembered: “Candidly, we were very, very successful. It was four years before we lost a case.”

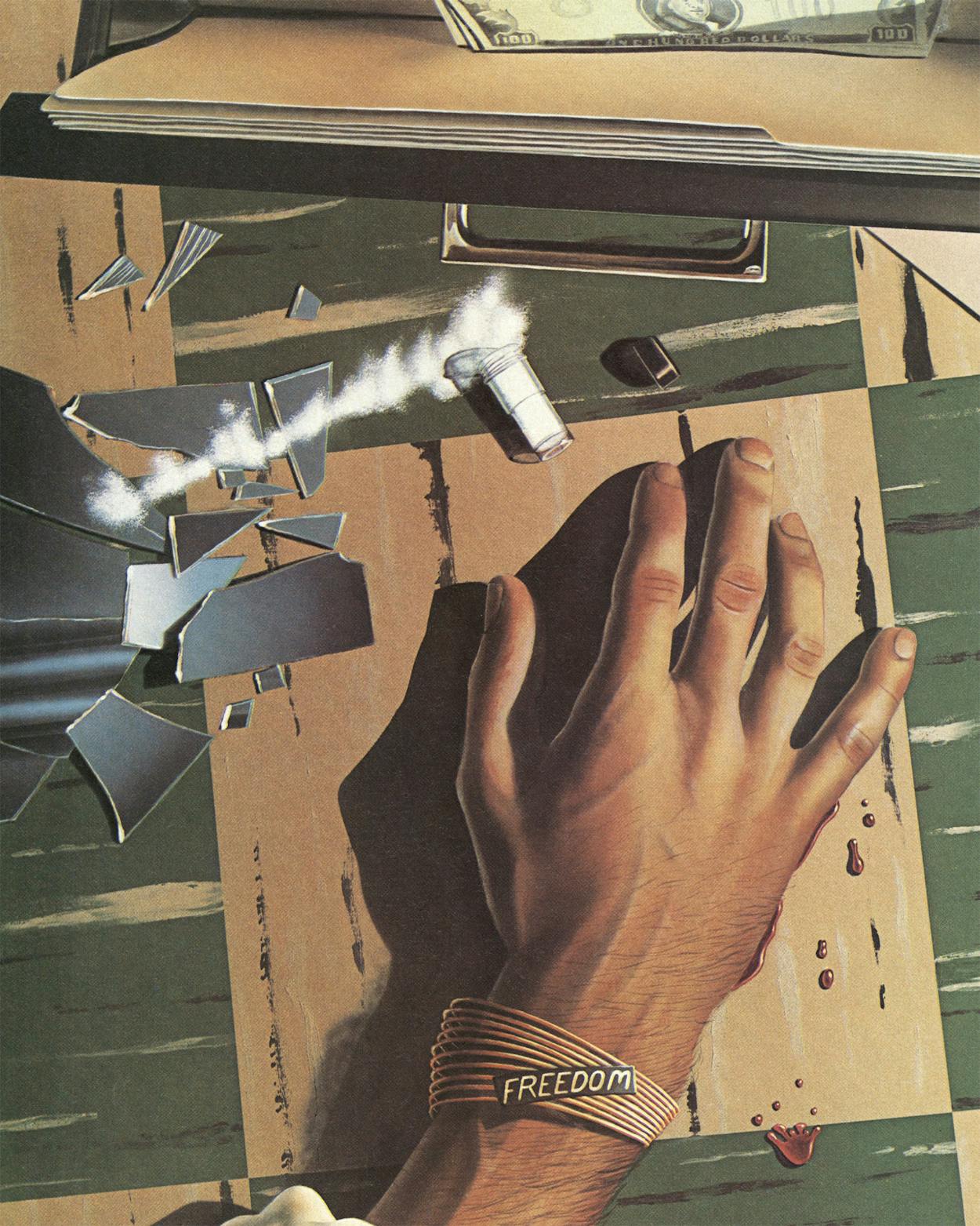

Lee adopted a wardrobe suitable to his image—a black cowboy hat, fancy handmade boots, and an assortment of expensive jewelry, including a gold bracelet that spelled the word “freedom.” He had several of the bracelets made for close friends and members of the family. Later, Jo Annie gave him an ebony cane with a gold satyr’s-head handle. It became his trademark. Fighting seemingly hopeless causes became his passion. Part of the reason was his honest conviction that even the lowest, meanest, rottenest scum on the face of the earth deserved, and in fact were guaranteed, a right to a fair trial. Part of it was the publicity: Lee loved to see his name in headlines. Part of it was his steadily increasing need for money. Part of it was paranoia, his gut instinct that some malevolent authority was watching and waiting, and part of it was the sort of perverse obstinacy that makes some men walk through a wall rather than open a door.

Scoring Big

Lee had already made a name for himself before he began taking drug defendants, but the string of cases that would make him one of El Paso’s most famous—or infamous—figures began in the early seventies when U.S. customs agents busted a smuggler from Tennessee named Tom Pitts and two other men who were attempting to bring six hundred pounds of marijuana across the Rio Grande. Since he was a stranger to El Paso, Pitts asked a local smuggler named Jack Stricklin for the name of a good lawyer. Stricklin hadn’t yet met Lee Chagra, but he knew Chagra’s reputation. “I’d grown up in El Paso,” Stricklin recalled. “I didn’t trust Arabs. But everyone said Lee was the best.” Pitts arrived at Lee’s office looking like a hippie who had just crawled out of a Goodwill box but acting like the owner of a seat on the New York Stock Exchange.

Chagra laid out the cold, hard facts: “I can’t save you. You’re going to get five years each. You’ll do at least eighteen months. And I’m going to charge you ten thousand dollars.”

Lee meant $10,000 for all three defendants, but Pitts didn’t understand that. Pitts fancied himself a big-timer and concluded that Chagra must be pretty big himself if he was demanding thirty grand. The Tennessee dope dealer rolled down his sock and slapped the cash on Lee’s desk. Lee didn’t say anything. He just picked up the money and tossed it in a drawer. But his eyes spun like a blur of cherries on a slot machine.

It took Lee less that half a day to discover that the search warrant used to bust the Tennessee smugglers was faulty. Case dismissed. Soon every drug dealer on the border carried one of Lee Chagra’s cards. Some of them deposited large sums in the lawyer’s safe, against the inevitable.

Lee’s success in trying drug cases soon led him to meet Jack Stricklin, who had sent the Pitts case his way. Stricklin was an enterprising and likable young man who had grown up in one of El Paso’s better neighborhoods. His father was a vice president of El Paso Natural Gas. Stricklin started peddling lids when they were still lids—an ounce of grass in a Prince Albert tin. By the late sixties he had put together an organization capable of moving tons of marijuana across the river. Narcotics agents believed that Stricklin and his associates supplied a good part of the South and Southwest with Mexican marijuana.

Despite the differences in background and age (Stricklin was almost ten years younger), Chagra and Stricklin became more than lawyer and client; they became close friends. Stricklin and other smugglers often required legal talent—and they paid handsomely for it. Lee Chagra grossed more than $250,000 in 1972. The next year he paid taxes on $450,000, including $125,000 declared as gambling winnings. That was the year Lee and Jo Annie started building their new home on Frontera Road in the Upper Valley. Lee referred to it as “the mansion that Jack built.” It was 6500 square feet, with pool and stables, electronically operated gates, and closed-circuit television monitors.

Paying the Price

It looked as though Lee had struck gold, but quicksand might have been closer to the truth. It was the era of the Nixon Administration’s much-heralded war on drugs. A shake-up of the entire federal drug enforcement apparatus was under way, ramrodded by Nixon’s ranking authority on drugs, G. Gordon Liddy. Liddy came up with one farfetched idea after another. He helped develop Operation Intercept, a massive media event in which millions of U.S. citizens were stopped and searched at the border. He discussed with the CIA the possibility of “liquidating” all major drug traffickers in the Middle East; it was estimated that 150 key assassinations would do the job. Another suggestion was to disrupt the drug market by passing out poisoned drugs.

One strategy that Liddy and the newly created Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) finally settled on, as defense lawyers in El Paso soon realized, was the use of agents provocateurs, whose job it was to create crime. Over the years lawyers encountered scores of cases in which citizens had been lured into crimes by what amounted to federal bounty hunters. A case in point was that of an unsuspecting El Paso cafe owner who was conned by two agents into conspiring to buy stolen government weapons. The weapons existed only in the agents’ imagination, but at one point the trap got so bizarre that the poor cafe owner believed he was negotiating for a used submarine. “It was a totally ludicrous story,” Sib Abraham recalled, “but it got very serious when the jury convicted him.” In time, Lee and Sib became targets themselves. As his friend Clark Hughes warned him, “One of the problems with being a criminal attorney is that all your clients are crooks. If you’re not careful, your friends become crooks, too.” Lee first had the dangers of his association with criminals brought home to him in 1973.

In the early summer of 1973 Lee experienced for the first time in his life how it felt to be on the other side. On June 20 a team of narcotics agents appeared at his law office with a warrant for his arrest and hauled him away in handcuffs. A grand jury in Nashville had indicted Chagra and forty others on a charge of conspiracy to import and distribute marijuana. A few hours later, the 38-year-old attorney, stunned and bewildered, found himself being transferred to the county jail, handcuffed to Georgie Taylor, who was a legend in local drug circles (he had made a million before he was eighteen) and who happened to be Jo Annie’s nephew. Although Jo Annie appeared at the federal courthouse with $50,000 in bail money, Lee was obliged to spend the night with Georgie Taylor, Jack Stricklin, and virtually the entire hierarchy of El Paso drug trafficking.

The indictment was so vague as to make it impossible to respond or even to contemplate a defense. The charges against all the defendants were eventually dropped, but not for two years. The media reported that the charges were dropped for lack of a speedy trial. In fact, the charges were dismissed because there was no evidence to bring charges in the first place. A scathing memorandum written in March 1975 by the chief judge of the Middle District of Tennessee declared the indictment to be “obviously and fatally defective.” He also said it was “so worded as to be utterly meaningless, and therefore, the indictment actually charged nothing at all.” Judge Frank Gray, Jr., went out of his way to rebuke agents of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and federal prosecutors, declaring that the restraints on the defendants’ liberty and their being forced to live for two years under “a cloud of anxiety, suspicion, and often hostility” violated basic principles of justice. Much later, Lee Chagra learned that the single piece of “evidence” against him was a statement made by Tom Pitts, claiming that he and another drug dealer had once used Lee’s office to cut a deal.

The months of suspicion and hostile publicity almost wrecked Lee’s law career. “Hardly anyone wanted a lawyer who was under indictment,” recalled Joe Chagra, Lee’s youngest brother, who by then had joined the law firm. “Even after the charges were dismissed, there was still the stigma. Every time the local papers wrote anything about Lee, the story started with ‘Indicted drug trafficker Lee Chagra . . .’ ”

Lee never forgot or forgave. His dislike for narcotic cops, particularly agents provocateurs, had been stoked to a white-hot hatred that nearly consumed both his private and his professional life. He began taping most of his telephone conversations and collecting every scrap of evidence that even hinted of government malfeasance. He filed a freedom-of-information request demanding that the government furnish him with all documents relating to its investigations of him, and before long the files filled two heavy-duty storage boxes. The documents revealed that hardly a week passed without some agent’s making inquiries into Lee Chagra’s private life. His office and home telephone records as far back as 1970 had been subpoenaed, and so had his income tax records. Almost every one of Chagra’s clients who had been sent to prison reported visits from DEA agents who pumped them for information about Chagra and offered deals if they would incriminate him. From time to time agents provocateurs posing as clients came to his office to discuss a phony case, then ended up trying to score some drugs from him. Lee developed a standard ploy – he secretly taped the conversation, then gave the agent the phone number of “the real Mr. Big.” It was the unlisted number of the local DEA chief.

Despite, or perhaps because of, these tactics, agents of the FBI, the IRS, and especially the DEA became convinced that Chagra not only was involved in international drug trafficking but was in fact the mastermind, the kingpin.

His Brother’s Keeper

The feds reasoned that Lee was the mastermind because Lee was so smart, and they became so preoccupied with this scenario that they failed to see the obvious irony: Lee was too smart to play that role. And yet, right there under their noses was another Chagra not at all handicapped by brains or good judgment. Lee’s younger brother Jimmy, who grew up hustling and hanging out with some of Lee’s more prosperous clients, wanted nothing more than to be recognized as Mr. Big.

The consensus had always been that Jimmy Chagra would never amount to much. He was the black sheep, the all-star goof-up. In some ways, they said, he was like Dad Chagra, old Abdou, a man stunted by his dreams. Lee had wanted to be a lawyer, and so, after some convincing, had the youngest of the boys, Joe. Patsy, the second, was the “miracle baby,” born against all odds and medical opinions; on the morning of her birth Abdou walked barefoot to the summit of Sierra del Cristo Rey and dropped to his knees and thanked the Virgin. Jimmy was born four years later, and they soon nicknamed him Little Mischief. He was a mama’s boy, always pouting and complaining. When things were going poorly for him—and they usually were—he could be amazingly rattlebrained and cruel. When Patsy, who at one time weighed 180 pounds, finally worked up the courage to wear a swimsuit in public, Jimmy humiliated her mercilessly. She had worn a pair of panty hose under the suit and as they were cruising out in the middle of a lake in Joe’s speedboat, Jimmy called everyone’s attention to her bizarre outfit and ripped her panty hose in one thigh. “A big blob of fat came pouring out,” she remembered. “Jimmy couldn’t stop talking about it.”

Still, everyone loved Jimmy and took care of him. They had to take care of him because he spoiled everything he touched. He ruined his marriage to Vivian, left her and the children. He nearly bankrupted the family carpet store and maybe even helped along Dad Chagra’s fatal heart attack. He ran a floating blackjack game and started peddling dope. He gambled in Vegas and wrote bad checks and was constantly calling Lee to bail him out. They say Jimmy lacked ambition. They say there was nothing Jimmy really wanted to be, but that wasn’t entirely true. Jimmy wanted to be Lee. He wanted to dress the way Lee dressed, in fine clothes and jewelry, and he wanted to hear whispers of respect when he walked into a room and silence when he told a story. Sometimes Jimmy pretended he was Lee, signing his name Lee Chagra and repeating Lee’s stories as though they had happened to him.

For years there had been a rivalry between the two brothers, a fierce and unyielding competition that only the two of them completely understood. Lee protected Jimmy, but he also contributed to Jimmy’s sense of inadequacy. Paradoxically, though, Lee was secretly jealous of Jimmy. Lee fought like hell for everything he had, but things came easy for Jimmy. And Jimmy seemed better able to laugh off the competition between them. He wanted everything his brother had, but he just didn’t want to work for it. In the summer of 1975, Jimmy finally hit the big time. The idea originated with a friend of his, a highly decorated former Army helicopter pilot who was rumored to have Mafia connections, and with Jack Stricklin, who provided most of the technical expertise. But Jimmy took most of the credit. The scam brought in more money than Lee had ever thought of making in his law practice.

It was four years before most people recognized Jimmy’s achievement, but the operation was a landmark in marijuana trafficking. It was the first time anyone from El Paso had thought of using a tramp steamer. Instead of flying in the customary small planeload of 2000 pounds from Mexico, they imported 54,000 pounds from Colombia. They landed the high-priced weed at a deep, remote cove on the northeastern point of Massachusetts Bay, near Boston. It took three days for an ingenious pulley apparatus to hoist the 100-pound bales to the top of the cliffs. It took almost a year for all the money to work its way back to Jimmy and his partners. The best guess is that they divided at least $5 million.

Lee’s position in this venture was that of highly paid legal adviser for the gang of smugglers. The feds could never prove he had any part in the operation or even that he knew about it in advance, though he probably did. He certainly knew about it before the feds did. And when it came to squandering the profits, Lee was at the head of the line.

Firing at Vegas, Part I

The next summer the Chagra brothers hit Vegas like a blizzard of kamikaze locusts. The money from the big score in Massachusetts was pouring in, and Lee and Jimmy were racing to see who could lose it first. Folks in Vegas can be terribly blasé, assuming, as they do, that they have seen it all: Kentucky colonels, Arab sheiks, Latin American dictators, Houston oilmen, French industrialists. Hunter Thompson once described how a casino shot a three-hundred pound bear out of a cannon right in the middle of the floor and no one looked up. But Vegas had never seen anything that surpassed the performance of Lee and Jimmy Chagra.

Lee drew a crowd simply by walking through the front door at Caesar’s Palace, passing out money, and asking how much they loved him. “Do you love me, do you love me?” He knew the answer, but he had to hear it again. Everything was on the house. On five minutes’ notice, Caesar’s would dispatch a Learjet to fetch one or both of the Chagras. People in the Chagras’ party didn’t bother to register: they just walked up to the desk and someone handed them a key to a six-room suite. Jimmy preferred the Sinatra penthouse with its white baby grand piano and spiral staircase. Food, drinks, girls—anything one might fancy was there in a whisk.

The real show was on the casino floor in special sections roped off for the Chagras. Security guards kept the riffraff away. Only a few select friends and celebrities like Rosey Grier or Gabe Kaplan were allowed in. When an average high-stakes player sits down at one of the seven places around a blackjack table, his limit might be as high as $1000 a hand. Lee’s limit was $3000, and he would have played for $10,000 had Caesar’s Palace allowed it. He had $250,000 credit. Eventually, Jimmy’s limit was $10,000 a hand and his credit almost unlimited. When either of the Chagras sat at the blackjack table, he took all seven spots. Lee loved being at the middle of the table, flanked by armed guards and at least one beautiful “broad” who would act as his lucky piece. They could barely deal fast enough for Lee . . . all the spots covered with white chips, $21,000 riding on every deal.

Curiously, this kind of heavy action seemed to bring out the best in Jimmy and the worst in Lee. When Lee hit a losing streak, he could fly into a snit, blaming anyone handy, especially Jo Annie, who more than once hurried off the casino floor in tears. Jimmy, on the other hand, had a true gambler’s instinct, a fatalistic kill-or-be-killed attitude. “Lee couldn’t hold a grudge, but Jimmy was the kind who would get you by the balls and never let go,” said Jimmy Salome, a longtime family friend. “For pure gambling, Jimmy may have been the strongest anyone in Vegas ever saw. There have been people who gambled higher in one sitting, but week after week, month after month, nobody kept coming, kept flat firing at ’em, like Jimmy Chagra.”

Then suddenly the money was gone. By early autumn 1976 Lee was back in El Paso, pumping money. He hustled personal injury cases, divorces, wills. He was practically chasing ambulances.

“Lee didn’t seem at all depressed,” said Donna Johnson, the law firm’s bookkeeper. “He was really happy that all the money was gone and he had to work again. Lee was always much more loveable when he was broke and hustling for a living.”

The Beginning of the End

One client who occupied a good deal of Lee’s time during the autumn of 1976 was Jerry Edwin Johnson, a local con man and admitted drug smuggler accused of masterminding a scheme to defraud the IRS of a quarter of a million dollars. He was already doing time on the fraud charge at La Tuna federal correctional institution, which was on the New Mexico state line not far from El Paso. Now the government was trying to prove that Johnson had helped smuggle a pound of heroin out of Mexico.

What Lee didn’t know at the time was that Johnson had, as they say, “gone over.” He’d become a government snitch, albeit not a very reliable one. In a secret interview with a group of DEA agents and prosecutors, Johnson had implicated at least sixty El Paso citizens as major drug traffickers. There wasn’t any Mr. Big, Johnson acknowledged, but if the narcs preferred to look at it that way, Lee Chagra was as good a name as any. The interview was patently leading; most of the questions were of the when-did-you-stop-beating-your-wife variety. A sample:

Q.—What about Lee Chagra? Is his [dope smuggling] operation totally separate [from another smuggler’s]?

A.—I think now it’s a separate deal . . . I’m not sure.

The agents thought so little of the information gleaned in the interview with Johnson that they didn’t even bother to place him under oath. “I think Jerry Johnson told us whatever he thought we wanted to hear,” DEA agent J. T. Robinson later admitted. The fifty-page text of the interview was used as supplemental material by a grand jury investigating a tax fraud, but it was never given the slightest weight as courtroom evidence. By law, the interview was to remain a secret, known only to a handful of agents and prosecutors who read the transcript as part of their official duties. Instead, this flimsy, highly prejudicial document was destined to dog both Lee Chagra and his nemesis, Judge John Wood, to their graves.

For the time being, the Jerry Johnson episode played itself out in obscurity, but the Chagra name burst into the headlines in the opening days of 1977. The news that a task force of federal and state agents had seized a DC-4 with 17,000 pounds of top-grade Colombian marijuana in Ardmore, Oklahoma, on December 30 hit El Paso like a sonic boom. (At that point the public had no inkling of the earlier, even bigger Boston haul.) By New Year’s Day it was the top story in town, and the defendants were being called the El Paso Ten. Though Jimmy Chagra’s name was never officially mentioned, almost everyone assumed that he had masterminded the scheme. In a short time the bust was being described as the biggest one in El Paso history. The fact that Lee Chagra was the lead attorney automatically made the case big-time. Hardly a day passed that the flamboyant attorney didn’t make the news.

Before the case could be brought to trial, however, Jimmy eclipsed his brother in the headlines with a new and even more spectacular exploit. Jimmy had chartered a jet and attempted to rescue an El Paso pilot who had been badly burned when a DC-6 crashed on takeoff at an improvised field near Santa Marta, Colombia. Jimmy and the crew of the chartered jet were arrested by Colombian authorities. No charges were filed, but it was apparent that the crash was another of Jimmy’s scams gone up in smoke.

Back in El Paso things weren’t going much better. Family problems were accumulating faster than Lee could catalog them. Jo Annie was talking about divorce; she and Lee got as far as the courthouse steps before one or both backed out. Joe was talking about resigning his partnership in the law firm. Jimmy was just talking. Even as Lee was working to salvage what he could from the ruins, Jimmy was plotting a new deal. Several times Lee talked to Vivian and others about dying. “I don’t know how much longer I can do this,” he confided. He had started using cocaine some months earlier, and now he was using it daily. On top of everything else, he had developed hemorrhoids and they hurt like hell.

Coming as it did in the midst of his misery, Lee’s brilliant defense of the Ardmore bunch had to be his most satisfying victory. The boys had been caught red-handed with 17,000 pounds of marijuana. That was a fact. Ten smugglers, two airplanes, and four U-Haul trucks had been seized in the predawn trap. Another indisputable fact. And yet by the end of the trial, a majority of the jurors refused to find the defendants guilty.

“The greatest job of bullshit advocacy I’ve ever seen,” Clark Hughes said of Lee’s performance. Hughes, who assisted in the defense, thought that Lee won in his opening remarks to the jury. Chagra used one of his trademarks, a solid-gold retractable pointer, to demonstrate his case. With the pointer fully retracted, Lee approached the jury box, smiling. He touched the tip of the pointer and said, “This small tip represents innocence: the defendants didn’t do a thing. This other end represents guilty beyond a reasonable doubt: the government proved its case, and you, the jury, are convinced beyond a moral certainty.” Lee held the members of the panel with his eyes, pausing for a few seconds so it could all register. Then he expanded the pointer, an inch at a time. “The rest of it,” he said, his voice sure and unwavering, “represents not guilty.” As he said the words, Lee extended the pointer to its full length.

As the defense had expected, several officers testified that they had arrived at the airstrip in time to witness the off-loading of the DC-4. When Lee pinned them down on the exact location from which they had watched the scene, several jurors snickered: not only was the position almost a mile from the field but a massive hill blocked the view. The government was so rabid for convictions that it destroyed its own case. Each time he caught a narc in a lie, Lee made eye contact with various jurors, the corners of his mouth twitching with mirth as though he expected tiny okra plants to sprout from the witness’s nose at any moment.

By the time the jury began its deliberation, it was obvious that the best the prosecution could expect was a tie. After two days the jury reported itself hopelessly deadlocked, eight to four for acquittal. At the victory party that followed the declaration of mistrial, one of the jurors told Lee: “I know those boys did everything they said they did, but dammit, they didn’t prove it!”

Three Nemeses

Lee got the best of the feds in Ardmore but that was about the last time. The government had been after him ever since Nashville, but 1977 was to be worse than anything that had gone before, largely because of three men: U.S. attorney Jamie Boyd, Boyd’s assistant James Kerr, and Judge John Wood.

Jamie Boyd was the consummate politician. In his eleven years on the El Paso political scene, Boyd had been elected to public office only one time, to fill out the unexpired term of district attorney in 1970, and yet no politician in town had a better feel for the bureaucracy or for subtle shifts in power and opinion. By maintaining close ties to Democratic Party kingmaker Travis Johnson, Boyd had run the gamut of offices: assistant county attorney, assistant U.S. attorney, district attorney, U.S. magistrate. During his tenure as magistrate, Boyd and Lee Chagra became friends, and when there was an opening for the job of U.S. attorney after Jimmy Carter’s election in 1976, Lee, Sib Abraham, and others supported Boyd’s appointment.

Boyd had never been regarded as a crusader, but one exception was his views on gambling—he hated gamblers. The shotgun murder of an Oklahoma gambler in El Paso some years earlier had convinced him that the “Dixie Mafia” was making a power play in El Paso, and he had instigated a controversial grand jury investigation. Despite all evidence to the contrary, he had refused to let go of the notion that El Paso was being overrun by the Mafia.

To combat what he perceived as the inroads of organized crime, Boyd needed someone tough and relentless to take over the El Paso docket as federal prosecutor. He decided on James Kerr, one of the assistant U.S. attorneys he had inherited from the Republican regime. A graduate of SMU’s law school, Kerr had worked for the Justice Department and helped draft the 1970 Drug Control Act. Later he built a reputation as a hard-driving prosecutor in charge of the docket in Del Rio, where he and Judge John Wood became fast friends. This friendship, the fact that the prosecutor and the judge were seen socializing so often, caused some lawyers to question Wood’s impartiality. “A judge can’t associate socially with a prosecutor the way Wood did with Kerr and still call ’em correctly,” John Pinckney, the first U.S. attorney, had said.

Kerr’s long association with FBI, IRS, and DEA agents—clients, he called them—had convinced him of the same sort of monolithic conspiracy that Boyd himself leaned toward. Narcotics and gambling were crimes that grew from a common stem composed of the worst elements in society. Composed of, and by, organized crime. The Mafia!

“Kerr was an empire builder,” Boyd said. “I knew he would take a hard look at narcotics and organized crime.”

As Boyd must have realized, Kerr and Lee Chagra were natural enemies. Lee despised Kerr, and Kerr had every reason to despise Lee. It was hard to imagine two men more different. Kerr was frail and sallow-faced and talked in a high-pitched voice that suggested he was about to shatter. Chagra had little use for public servants, especially prosecutors, and Kerr was a classic bureaucrat, squeaking with authority and wedded to the book.

Chagra’s idea of a good time was slapping a Willie Nelson album on the stereo, snorting cocaine, and getting naked in a pile of aromatic bodies. Kerr preferred playing Bach fugues in the dim light of the First Presbyterian Church and going to the symphony. Kerr thought Chagra was vulgar and common, and Chagra enjoyed enhancing this image by slipping up behind Kerr and whispering things that made the prosecutor blush. Chagra could win or lose more in a single session at a Vegas crap table than Kerr made in a year. Kerr claimed that money didn’t matter, that his mission in life was “vigorously and, I hope, successfully” prosecuting all offenders that his clients could provide, but the mere fact that his adversary put such emphasis on money and the trappings of wealth must have touched some deep reserve of resentment in him.

In Judge John Wood’s courtroom Kerr found the perfect forum for his crusade. Like Julius Caesar, John H. Wood was several times offered high office, and several times he refused. It was only in 1970, after Senator John Tower and other ranking members of the Republican Party in Texas made personal pleas, that the staunch Republican lawyer agreed to accept a federal judgeship for the Western District of Texas. Wood was finally convinced that it was his duty. The nation was at war, not only in Viet Nam but in the streets, alleys, and barrios of America, where the menace of drugs was destroying the will to fight, or to work, or to do almost anything of traditional value.

Although Wood had devoted his career to civil law, there was no more ardent law-and-order advocate anywhere. It was in his blood. His great-grandfather had come from New York and fought in the Texas Revolution. His grandfather had been an ironfisted sheriff of Bexar County when lawmen still fought off Apaches. No man could have been prouder of his heritage than Wood; he was a confirmed, unapologetic elitist, a descendant of hardy pioneer-stock aristocrats. The judge was a member of every exclusive club in San Antonio—Sons of the Republic of Texas, Sons of the American Revolution, Texas Cavaliers, Argyle Club, San Antonio Club, Order of the Alamo, San Antonio Gun Club, German Club, American Legion, San Antonio Country Club—and owned property in the segregated Key Allegro resort on the Texas coast—the list went on and on.

In January 1971 Wood was sworn in as a U.S. district judge, with jurisdiction over about a quarter of the El Paso docket. He inherited the whole El Paso docket in 1974 when Judge Ernest Guinn died suddenly of a heart attack. Wood’s first big drug case came in May 1971. The defendant was one Melchor de los Santos, who was caught with 262 grams of heroin; since the going rate was $30 a gram, it was a fairly substantial bust for the times. Maximum sentence was 15 years on each of three counts, and that’s what the judge gave him—45 years. Over the next eight years Wood handed out the maximum sentence in almost every case. He bragged that he never once granted probation in a heroin case. It wasn’t just in hard-drug cases; Wood appeared to make no distinctions. He once sentenced a dope dealer to 35 years for contempt of court. Whatever the maximum penalty was, that was generally what he gave. The bonds that he set in marijuana cases averaged $200,000. His harsh, unbending policy of sentencing and his blatant pro-prosecution posture astonished lawyers and embarrassed other judges, including those that sat on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. In short order, Wood surpassed Guinn’s unenviable reputation as the most reversed judge in the district. This didn’t seem to disturb Wood any more than it had Guinn, who used to cackle, “I can sentence them a lot faster than they can reverse them.” Nor did Wood protest when they started calling him Maximum John. He loved it.

Kerr Closes In

On April 11, 1977, James Kerr made an unpublicized trip to Nashville to review the allegations of the 1973 indictments against Lee Chagra and Jack Stricklin. The case had been dead for two years, but Kerr had a plan. His plan was to reindict Stricklin, and maybe Chagra too, under an almost unknown section of the 1970 Drug Control Act that spelled out the crime of “continuing criminal enterprise,” popularly known as the kingpin act.

In the seven years or so that it had been in on the books, few had bothered to read that section of the drug law. The language was vague and ambiguous, but essentially it said that a person was a kingpin if he (1) committed a continuing series of violations of the drug act, in concert with “five or more other persons with respect to whom such person occupies a position of organizer, a supervisory position, or any other position of management” and (2) obtained “substantial income or resources” from those violations. The law was wide open to interpretation—tailor-made for a crusading lawman like James Kerr.

But the real bite of the law, the element that made it harsher than any other federal law on the books—harsher even than penalties for rape, murder, or kidnapping—was its inordinate range of sentences. Minimum sentence was ten years, maximum was life. And that wasn’t all. Defendants convicted on a kingpin rap were not eligible for parole, period.

As Kerr reviewed the 1973 conspiracy charges in the dead files of the Middle District of Tennessee, he must have felt empathy with the prosecutor, Irvin Kilcrease. There were at least twenty lawyers for the defense, but apparently the entire burden of prosecution fell on poor Kilcrease. It was obvious that the prosecution and the DEA had problems coordinating their investigation. In fact, many aspects of the case were never investigated. Kerr had the advantage of interviews with a number of dealers who had been arrested since 1973—one informant claimed he had personally paid Stricklin $500,000. From Kilcrease’s files, Kerr concluded that all the elements needed to satisfy the kingpin law were amply present—many separate transactions and many people, most of whom worked for Stricklin. Or for Lee Chagra. If you scratched Stricklin deep enough, Kerr reasoned, you would find Chagra.

Shortly after the Ardmore trial, DEA agents visited Jack Stricklin at La Tuna federal correctional institution, where he was doing time for a drug rap Lee hadn’t been able to get him out of. “You help us and we’ll help you,” the agents told Stricklin. They wanted information on the real kingpin of dope trafficking in El Paso. They mentioned four names—Lee Chagra, Jimmy Chagra, Sib Abraham, and Vic Apodaca (a well-known bail bondsman). If Stricklin cooperated, they would work for his early release. If he refused, they would see that he was reindicted under the kingpin act and sent away for life without parole. They showed him a Xerox copy of the section of the law dealing with continuing criminal enterprise.

“Do yourself a favor,” one of the agents said. “One way or another, we’re gonna get Lee Chagra.”

Stricklin looked at the copy of the law for a few seconds, then returned it to the agents. “Fold this five ways and stick it where the elves don’t play,” he said. A month later, Jack Stricklin was standing before Maximum John Wood, contemplating life without parole.

At first Lee wasn’t terribly worried about the new charges against Stricklin. “Kerr’s just working the tailings,” he said. The case against Stricklin appeared to be nothing more than a rehash of the long-discredited Tennessee indictment mushed together with evidence from the deal for which Stricklin was serving time. It appeared to be a clear example of double jeopardy—same events, same evidence, same witnesses. If there was a single piece of new evidence, it wasn’t mentioned, or even hinted at, in the indictment. The government seemed to know it didn’t have a case, but it was determined to see how far it could travel. In the court of John Wood, Chagra realized, that could be some distance.

The Family Cracks

In the summer of 1977, sensing the heat but also attracted by the opportunities being suggested by his new partner, a wily, borderwise ex-con named Henry Wallace, Jimmy told Lee he was moving his base of operations to Florida. Lee concurred and told other members of the family that Jimmy was dead broke and needed their help. Joe and his wife, Patty, who had been married for about eighteen months, sold some of their furniture and gave Jimmy some money and their Blazer. They learned later that Jimmy left town with about $50,000. “Which for Jimmy was almost the same as being broke,” Patty said. Lee flew to Florida and set up a dummy corporation for Jimmy. It was called Capital Acquisition, and its purpose was to channel funds through several banks in Mexico and then into Jimmy’s new business.

By now all the Chagras knew that Jimmy was a major drug trafficker, and they must have suspected that Lee’s arrangement with his brother and his relationship with Jack Stricklin were more than traditional lawyer-client dealings. Rumors persisted that while Stricklin was doing time at La Tuna, Lee arranged to destroy records that would have established Lee’s complicity in a number of smuggling operations. And yet federal agents still had no proof: for all the loose talk, there was not a shred of hard evidence that Lee had committed any crime. Lee had never let his name be linked to an illegal enterprise before the fact. Until now. The Florida operation had the potential to make millions, but it could also spell disaster for Lee. If the feds could compromise even a single member of the conspiracy, the whole organization might crumble—and Lee with it. By setting up the corporation for Jimmy, Lee had, for the first time, made himself vulnerable.

Joe Chagra told Lee he was a fool.

“You’ve got it wrong,” Lee replied. “I’ve been a fool.”

There was no bitterness or rancor, but by the end of August Joe Chagra realized that he had had all he could take. Joe was quieter and more introspective than his brothers. Gambling bored him. His idea of a good time was going home to his wife and newborn son, Joseph, maybe tinkering with his stereo or waxing his speedboat, swimming or lifting weights. He was a good, sound, all-around lawyer, but he didn’t have Lee’s appetite for controversy. When Joe and Lee had drawn up their partnership, the arrangement was that they would share all revenues and losses, but Joe hadn’t counted on sharing Lee’s gambling losses. “Every morning when I drive down to the office, I get sick at my stomach,” Joe told Patty. “I never know if we have fifty thousand dollars in our account or fifty cents.” He’d fought a lot of tough battles at Lee’s side, and he loved them because they were something that he and Lee did together. But lately Lee was taking new directions. Joe announced plans to open his own law firm. The family was breaking apart.

Wood’s Bombshell

On August 31, 1977, Lee Chagra appeared in Judge Wood’s court to file a motion of discovery, asking that the judge turn over DEA reports, customs reports, grand jury probes, any material that would reveal when Stricklin was supposed to have engaged in continuing criminal activity. Chagra argued that the indictment smacked of double jeopardy, but there was no way he could prove it until the government got specific.

In a written response the following week, Kerr reminded the court that although Lee Chagra was not named in the present indictment, he had been indicted in the Tennessee affair. Then Kerr observed that “the request for reports . . . is an overt act on the part of the defense attorney . . . to obtain government reports and documents concerning him.” That is, concerning Lee Chagra. “The government questions the good faith of this request,” Kerr concluded.

Borrowing heavily from Kerr’s own wording, Wood totally agreed: “This request appears to be primarily an effort by the defense attorney to obtain reports of an investigation pertaining to him. This conduct suggests to the court that the defendant is not making a good faith claim concerning former jeopardy, but that he is more interested in determining the extent of the government’s evidence against him.”

When he read copies of Kerr’s motion and Wood’s reply, Chagra was flabbergasted and then outraged. What investigation against him? It was Stricklin who was on trial, not Chagra. Lee had been accused of a lot of things, but this was the first time anyone had ever accused him of representing himself and not his client. Until now the media had treated the charges against Stricklin as routine news, but Wood’s ruling added a bizarre new twist. Reporters flocked to the federal courthouse to get a look at what was happening to Lee Chagra.

On October 20, 1977, as Chagra stood before the bench objecting to Judge Wood’s personal attack, arguing that it was totally without evidence or cause and that the resulting publicity had done great damage not only to Stricklin but to Lee himself, the judge interrupted and dropped his bomb.

“I imagine everyone in this area knows that you’ve been the subject of a grand jury investigation ever since the Tennessee indictment,” Wood announced. “Is there any secret about that?”

“Well, I didn’t know about it,” Lee said, dumbstruck. He had known that the DEA was watching him, but a grand jury? And even if it was true, for Wood to reveal it in open court was outrageous.

The judge said he had spent “eight or ten hours” reading Jerry Edwin Johnson’s 1976 grand jury testimony and the transcript of the IRS investigation. Wood was apparently confusing the fifty-page transcript of the secret interview with actual grand jury testimony. Technically and legally, the unsworn interview shouldn’t even have been a part of the grand jury report. Wood pressed on, however, announcing that the grand jury investigation concerned not only Lee Chagra and Stricklin; it also involved Sib Abraham and others. Out of the corner of his eye Lee could see the reporters scribbling furiously. Visions of the 1973 fiasco in Nashville that had almost ruined his law career danced through his mind. What was happening here?

Lee continued to object. He made a motion for Judge Wood to recuse (disqualify) himself in the Stricklin case. “I can’t practice in front of you, and I don’t think you can honestly say that you can treat me or my client fairly in any court,” Chagra told Wood.

Now it was the judge who was having difficulty. Wood began to crawfish. “I have never found anything,” he said pleasantly, “in any of these grand jury investigations. That’s the reason I’m going to release it to you. . . . That’s what I’ve been trying to tell you. I have not seen anything that would actually disqualify me from trying this case.” Eventually Wood agreed to give Lee a copy of the Johnson interview but refusing to remove himself from the Stricklin case as Chagra requested. Technically Lee had won the battle, but there was little doubt that Wood had landed a crippling, perhaps fatal blow to the attorney’s already battered reputation. Wood’s blunder was the last straw. Lee and Joe began to consider filing a harassment suit against Wood, Kerr, and various federal agents.

There is no way to calculate how all the damning publicity affected the careers of Sib Abraham and the others. Lee’s law practice never recovered. Over the next year Lee had only a handful of cases. The tragedy was that it was all unnecessary: before the Fifth Circuit had a chance to rule on the question of jeopardy, Jamie Boyd decided to drop the continuing criminal enterprise charges against Jack Stricklin.

Firing at Vegas Part II

One weekend after the fiasco in Judge Wood’s courtroom, Lee Chagra did what he always did when he felt the world collapsing around him—he telephoned Clark Hughes and suggested a trip to Las Vegas. Hughes knew these had been hard times for his friend. Chagra and Wood were on a collision course that was bound to end in catastrophe.

Jimmy and his new business partner, Henry Wallace, were in Florida awaiting their first freighterload of Colombian marijuana, and from what Lee had heard, the operation had all the earmarks of a disaster. Lee’s finances were in shambles, but he still had plenty of credit in Las Vegas. No force on earth could stop him. “This is gonna be one they’ll write a book about,” he told Hughes. “I’m gonna take the joint apart.”

Caesar’s Palace dispatched a Learjet, and in less than two hours a limousine deposited them at the casino door. Lee handed out $200 in tips before they got to the suite. He always got excited the moment he felt the clamor and hysteria of Caesar’s but this time he was practically dancing on the walls. “For sheer élan,” Hughes recalled, “I don’t think I’d ever seen him any higher.”

Hughes knew that it would be several hours before Lee worked himself into the proper frenzy. There was a ritual that he always observed before going downstairs to the casino. First, he made at least a dozen telephone calls. Hughes never knew whom he called or why—Lee’s life was like a hornet’s nest, with thousands of isolated cells, and no one person, however close, ever saw more than a single cell. But the mere act of talking on the telephone seemed to boost his confidence. After the phone calls, Lee would take a long time—maybe two hours, maybe more—to bathe, groom, and dress himself in the wardrobe that he reserved for these occasions. Standing in front of the mirror, he would snap the pearl buttons of his red cowboy shirt, then climb into the black Western-cut leisure suit. He would attach his belt to the giant solid-gold buckle with the thick crust of diamonds, and draw on his black alligator cowboy boots. Checking himself again in the mirror, he would fuss with the black cowboy hat that had “Lee Chagra” and “Freedom” embossed in gold on the inside until he achieved the proper tilt and slope. Finally, he would pose with the ebony cane with the gold satyr’s-head handle, squinting and turning until he was satisfied. It was an incredible sight. Right there before your eyes Lee Chagra became the Black Striker.

Clark Hughes went ahead to the casino “to lose my piddling three or four hundred.” He never knew why Lee liked to bring him along, but he seldom refused. Lee was Clark’s friend, maybe the best friend he’d ever had, but in some strange, almost unthinkable way he felt the friendship slipping away. He had known about Lee’s cocaine habit, but since Clark had been appointed a judge, Lee hadn’t flaunted it. It wasn’t the cocaine so much as the lifestyle it symbolized. It was as if their friendship had come to a fork in the road, and Lee had wandered off in another direction.

It was almost midnight when the Black Striker made his appearance on the casino floor. At this point in his life Lee was bored with the tame pace of the blackjack table. He marched straight to a crap table on one side of the casino and told the pit boss to clear the table. The pit boss snapped his fingers and motioned for the guards to bring the velvet ropes. “Gentlemen,” he told the other players, “this table is now reserved for a private game. Please feel free to use any other table in the casino.” Like so many sheep, the nickel-and-dime players started backing away. At the same time a swell of excitement seemed to rumble from the floor, and people pushed to get a look at the action. As Lee reached for the dice, he recited a spiel that was also part of his ritual. “Look at ’em,” he grinned at the pit boss. “You ought to pay me fifteen hundred dollars an hour to entertain customers. Where do you get off? Who do you think you are?” The pit boss had heard the spiel many times and smiled patronizingly as he personally counted out the stacks of $500 chips. In the first minutes of Lee’s run, a little old lady burst through the crowd just as Lee released the dice. “Any craps!” she shouted, throwing a $5 chip on the table.

After about an hour Lee had lost $90,000. He didn’t appear particularly disturbed. He and Clark went back to the suite for a while. A short time later there was a knock, and Lee admitted two hookers to the room. It looked as though he was set for the night. Clark excused himself and went to his own room, alone.

Shortly after noon the next day, Lee telephoned and said: “Ninety thousand is nothing for a stepper. Let’s go downstairs and give them one they can write home about.” Clark said he would dress and meet Lee in the casino.

The casino was almost deserted. It was that strange hour when the golfers are still on their morning rounds and the drunks are still asleep, that time when they clean the sand in the ashtrays and empty the slots and put fresh ice in the urinals. By the time Clark arrived, Lee had already lost another $80,000 and was yelling at the floor manager because he was threatening to cut off his credit. “How come when I’m winning you let me do anything I goddam please, but when I lose you won’t let me out of the trap?” he shouted in a voice that could be heard in the coffee shop on the opposite side of the casino.

That night as he was dressing, Lee announced intentions to change his luck. He was going to play baccarat instead of craps. Clark was painfully aware that all serious gamblers harbored deep and irrational superstitions: once he’d seen Lee go berserk because a Chinaman approached the table. “I thought maybe I was the Jonah,” he said. “I decided to disappear over to the Hilton for a while.” When Clark Hughes returned to Caesar’s about nine that evening, Lee had almost exhausted his credit limit. In the 24 hours since their arrival, he had signed markers totaling $240,000.

They checked out of the hotel that same night and moved to the Aladdin, where Lee had a $250,000 line of credit. Once again, Lee went first to his suite and carried out the ritual. When he appeared several hours later in his Black Striker ensemble, a woman asked Clark Hughes if his friend was a movie star. The pit boss shooed the sheep away from table that Lee selected for his private performance. Unlike many casinos, the Aladdin allowed a player to lay double odds; thus it was possible to win or lose twice as fast. In less than fifteen minutes, he won $90,000. Clark assumed that he would go straight back to Caesar’s and claim some of his markers, but that wasn’t Lee’s plan. He did quit for the night, though. Some people though Lee Chagra didn’t know how to quit, but that wasn’t quite true. He knew how to quit while he was winning. Clark was dog tired and went straight to bed.

The following afternoon at the Aladdin, Lee took the worst beating Clark had ever seen him take. In a single short sitting he lost almost $190,000. He still had $150,000 credit, but that night he went through another $70,000.

They were scheduled to fly back to El Paso Monday morning. When Clark arrived downstairs with his luggage, he saw Lee at one of the blackjack tables, arguing with a Teamster guy who was apparently in charge of credit for the casino. Lee had seated himself at a table and ordered $5000 in chips, but the dealer refused. “Lee,” the man was saying, “I’m not gonna say this again . . . no more credit!”

Lee didn’t protest as Clark led him out of the casino to the waiting limousine. He looked as though he hadn’t slept for three nights. The silence was monumental. Lee stared out the limo window at the blur of cold neon. His cowboy hat was pushed forward until the brim almost touched his nose, and shaggy locks of graying hair spilled over his collar. Though neither knew it, this was the last time the two old friends would ever go to Vegas together.

After a while Clark said, “You must have dropped close to half a million back there. You sonuvabitch, how are you gonna pay off those markers?”

“I don’t know,” Lee said.

He took a deep draw on his cigarette and pressed Clark’s shoulder. “It’s like Teddy Roosevelt always said,” Lee told him, and now his smile was back in place. “It’s better to try. It’s better to bust your ass trying and get kicked all over tomorrow than live all your life like those little gray bastards out there.”

A few weeks after the Vegas trip, Lee was hospitalized for a long overdue hemorrhoidectomy. He was not very good at suffering alone, and friends and family visited him almost constantly. One day while Vivian was there, they delivered a dozen red roses to the room. Lee read the card and laughed. “It’s from some friends in Vegas,” he said, handing Vivian the card. The card read, “I hope your ass feels like what you did to us.”

Dying by Inches

For the most part, 1978 turned out to be just a continuation of the long slide that had begun in 1977. Except for a few faithful clients like Jack Stricklin, Lee’s practice was at rock bottom. Jimmy’s Florida operation, far from being an immediate disaster, disbanded after successfully offloading fifty tons of grass from a Colombian freighter in March. But as usual, Jimmy’s success only threw Lee into a funk.

As the feds worked around the clock to build cases against both Chagras, an agent provocateur came forward with information that could potentially put both of them away for life. The agent had wormed his way into the confidence of one of Lee’s protégés, a singer and part-time actor named Joe Renteria who was hot to start his own smuggling ring. With the agent providing invaluable assistance at every stage, Renteria and several others were drawn into the government trap. Jamie Boyd, who had known Renteria for years (the prosecutor once chaperoned him in a Boy of the Year competition), expected that once Renteria realized the seriousness of his situation he would name Lee as the kingpin. Boyd was wrong. Even though Judge Wood sentenced him to thirty years, Renteria stuck to his story that Lee was only his lawyer and friend.

Patsy Chagra’s husband, Rick De La Torre, faced four charges in the same conspiracy. Though the prosecution recognized there was hardly any chance that Rick would turn on his family, James Kerr did everything in his power to put him away for 40 years. This would be the last time Lee Chagra and James Kerr faced one another in a courtroom, a sort of last hurrah for both. It was a partial victory for Lee—the jury found De La Torre guilty of only one charge and he got the maximum, 5 years. But Kerr wasn’t satisfied. He wanted to indict De La Torre on five counts of perjury in an attempt to add another 25 years to the sentence—in effect, requiring him to defend his story to a second jury. Boyd felt that singling De La Torre out would be construed as the worst sort of sour grapes, and he insisted that Kerr submit the evidence to the Justice Department, which approved the new indictments.

But the feds’ real ace in the hole was Jimmy and his partner, Henry Wallace. What no one knew at this point was that the feds had already busted Wallace. In secret interviews Wallace was singing like a drunken angel. He had no information incriminating Lee, except that he confirmed that Lee had set up some dummy corporations to launder money, but he was willing to finger Jimmy as the kingpin. Boyd’s strategy was to indict Jimmy on multiple counts and wait for him to break. Boyd believed that one way or another Jimmy would take him to Lee. And he’d better. Boyd, Kerr, and the DEA had worked so hard selling the media on the contention that El Paso was the hub of dope trafficking in the Southwest that everyone took it as gospel. Now the feds had a yard of hot real estate on their hands; they desperately needed someone to buy it.

Whether or not he knew the details, Lee surely sensed the magnitude of the disaster that was bearing down on him. As the year progressed, so did his paranoia, his insistence that someone was out to get him. In fact, the only evidence that Lee expected things to improve was his new office complex. While it was being renovated, he occupied an office in a building on Montana owned by another lawyer friend, Mickey Esper, who was related to Jo Annie.

It was during this period that Lee was introduced to Mickey’s black sheep uncle, Lou Esper, a pale, seedy, rat-faced Syrian hoodlum who had spent about half his fifty years in prisons. Uncle Lou, who had recently been paroled in California, had a drug habit of long standing. He liked to mainline speed and supported his habit by organizing a small-time burglary-robbery ring using young black soldiers from Fort Bliss. When Lou Esper learned that Lee was a cocaine user, he found a good supply and usually delivered the goods in person. On several occasions he watched Lee remove one of his boots and count out the cash. Esper had also observed Lee making large cash payoffs to various collectors. Lee didn’t appear to like Lou Esper, but he was one of the few people in town who tolerated him.

Almost every day Jimmy telephoned Lee from his new home in Las Vegas. The family was worried about Lee. He seemed burned out, used up, and he was hitting the cocaine pretty hard. Clark Hughes had found a cartoon of a mouse shooting a finger at an eagle—it was called “The Last Great Act of Defiance”—and Lee’s secretary, Sandy Messer, was having it made into a wall plaque. On the cartoon, Clark had written “Wood” below the eagle and “Chagra” below the mouse. “No, you got it backwards,” Lee said when he saw it. “I’m the eagle!” But Sandy noticed there were tears in his eyes.

Lee cried a lot in those days. He cried when he thought of Jimmy. He didn’t advertise the fact, but Jimmy was helping to pay for the huge cost overrun on Lee’s new office. Jimmy was also taking care of Lee’s half-million-dollar marker at Caesar’s. Then, in a fashion that was typical of his relationship with Lee, Jimmy decided to take it one step farther. He went to the big guys at Caesar’s and told them that, by God, the next time his brother walked in that joint he wanted him treated like a goddam celebrity! That was it, Lee’s ultimate humiliation. He would never go back to Vegas. Jimmy had ruined it. Lee always suffered shamelessly when he was down and Jimmy was up, but this was different. He’d never cried about it before. Sandy and the others began to realize that this was something truly personal; it was as though Lee were mourning his own impending death. He talked about death a lot. It was becoming an obsession. His sister, Patsy, recalled, “It scared me to hear Lee talk like that. Lee had always been our strength.”

Lee couldn’t shake the feeling that something or someone was stalking him. He told Jimmy Salome that he was taking out a new insurance policy. He asked Bobby Yoseph, a young lawyer who had recently joined his staff, what he would do if he came in and found the office had been robbed? Before Yoseph could think of an answer, Lee asked another question: “What would you do if you came in and found I’d been murdered?”

This preoccupation wasn’t totally without foundation. Early in the fall someone had broken into Mickey Esper’s law offices and attempted to haul off a safe. Not long after that, someone attempted to rob a high-stakes poker game at Jimmy Salome’s house. Lee and several others heard the crash of metal against the patio door. Fortunately the glass was shatter-proof. Lee grabbed an old musket, the only gun in the house, and several of the poker players chased two black men across a field before losing them along the river. Lee speculated that the attempt was an inside job. Someone was supposed to open the door from the inside. “I thought it was just an isolated thing,” one player said, “but Lee kept brooding about it. As it turned out, he was right.”

By mid-November the feds had just about made their case against Jimmy Chagra, and rumors of his imminent indictment were rampant. James Kerr was devoting almost all of his time to his organized-crime investigation. The 38-year-old prosecutor had given up his apartment in El Paso and moved back to San Antonio, where he felt more comfortable.

Early on the morning of November 21, Kerr turned his car out of his driveway on a well-shaded street in the silk-stocking section called Alamo Heights and headed for the federal courthouse. At the intersection of Broadway a mint-green van blocked his route. Kerr was maneuvering his car around the obstacle when the rear doors of the van opened and two gunmen started firing. A blast of double-aught buckshot and .30-caliber slugs ripped across the hood, left fender, and windshield of the car: police officers later counted nineteen bullet holes.

For some unexplained reason, the three assailants (apparently there was a third behind the wheel) raced from the scene without bothering to walk five or six feet and make sure that Kerr was dead. If they had, they would have seen the small, trembling figure of the prosecutor crouched in a fetal position below the dashboard, dazed, bleeding from the shards of splintered glass, shaky as a bowl of gelatin—but otherwise unharmed.

The attempt on Kerr’s life unleashed the most sweeping drug investigation in the history of the Southwest. The next morning FBI agents called on Lee Chagra, confiscated his gun collection, and asked him to take a lie detector test. Chagra was outraged. “Would you ask Kerr to take a lie detector test if someone tried to kill me?” he demanded. The case remains unsolved.

“It’s David Long”

On the morning of the day Lee was murdered, his bookkeeper, Donna Johnson, arrived at the office about ten o’clock. Lee was already there. He’d brought corsages for all the women on the staff. He was wearing his boots and jeans and enough jewelry to sink a deep-sea diver. That old watch-me-carry-the-world smile was back on his face. He was bubbling over with tales of the previous day’s Tucson victory. Donna hadn’t seen him this happy in months.

The office was a maelstrom of activity, none of it having anything to do with the practice of law. Friends, relatives, and people that Donna had never seen before paraded through as though the place were a museum. The complex included not only a maze of well-appointed offices but also a fully equipped kitchen, a law library, and completely furnished two-bedroom suite. Donna made fresh coffee and explained the new telephone system to Lee. Lee sparkled like a kid with a new toy as he showed Donna and Sandy where the various safes were concealed. They knew about the safe in the floor of the bathroom, but there were others—one beneath the carpet near the fireplace in the living room of the private suite and another in the master bedroom. Lee had never discussed with any of the staff the purpose of the apartment at the rear of the complex, but they knew he was having a regular evening affair with a stripper from the Lamplighter Club. Most afternoons as Donna and Sandy were crossing the parking lot after work, they saw her, and sometimes two or three other strippers from the Lamplighter, hurrying toward Lee’s office. It was apparent from the manner in which the furniture was rearranged and toppled about that the orgies were quite vigorous.

As was his custom when he was in one of these expansive moods, Lee sat in his new office with his feet on his desk, telling war stories and handing out money. There was plenty of cocaine to guarantee a holiday spirit; at least five ounces had been delivered a few days earlier. Lee gave Jack Stricklin, now out of prison, $1000 and passed out lesser amounts to other old friends. During the course of the morning, a man called the Cowboy appeared on the alley TV camera. Donna had never seen him before, but Lee said that he was expecting the man and pressed the electronic button to admit him. Lee gave the Cowboy $10,000, and the others guessed that he was a collector for some bookie.

Lee kept detailed records of gambling transactions, but no one else had any concept of how much he bet or with how many different bookies. He had telephoned Sandy from Tucson on Friday and told her that a woman named Butch would stop by the office later in the day. Sandy was to count out $20,000 from the stash under the bathroom sink and have it ready when the woman arrived. This wasn’t an unusual request: just a week before, Lee had given Sandy $50,000 to carry around in her tote bag, ostensibly for safekeeping. Donna helped Sandy count the $20,000. They didn’t count all the bundles of cash in the tennis bag, but there was more money than either of them had ever seen in one place, something like $450,000. While they were counting, Bobby Yoseph appeared at the door and tried to shove his way inside. “I blocked the door with my body,” Donna recalled, “but he opened it enough to see the money.”