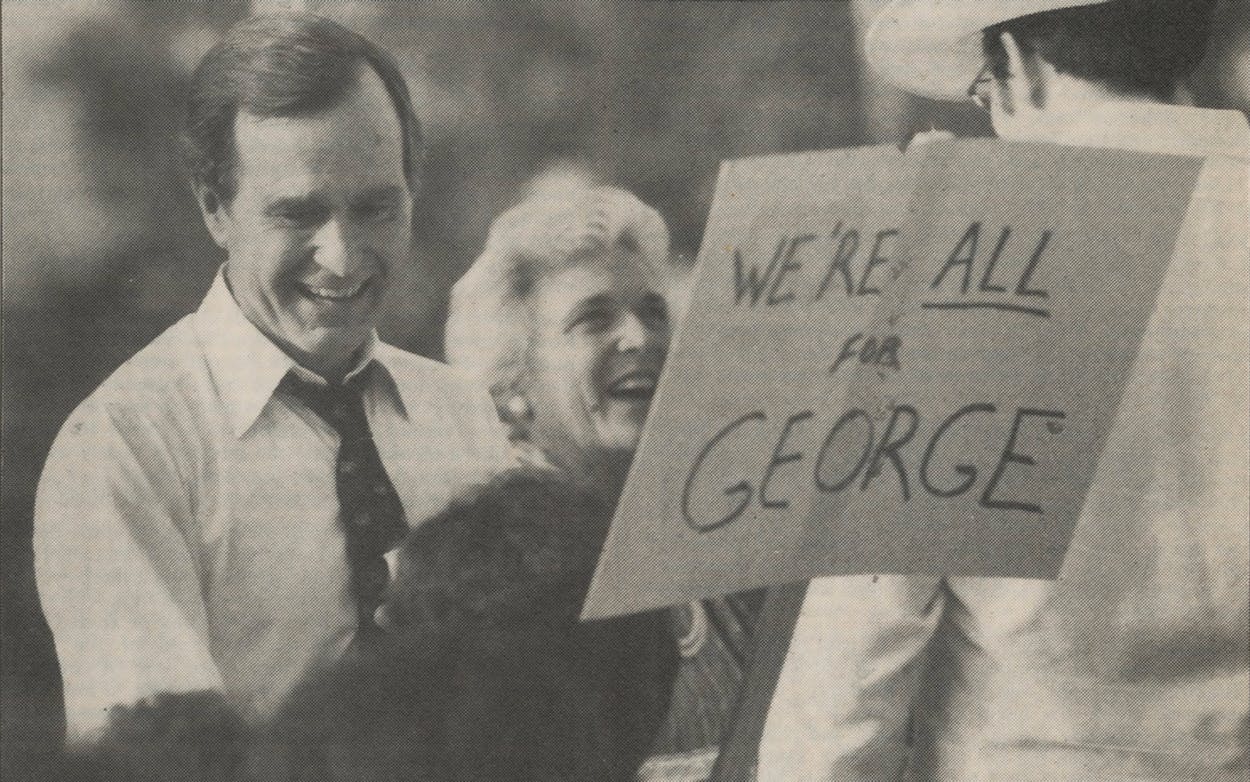

It is the Sunday after Thanksgiving, and the Houston airport is spilling over with people. One of them is running for president of the United States, but to the rest he remains anonymous, just another holiday traveler carrying his own suitcases. Substitute any of the glamour candidates—John Connally or Ronald Reagan or Ted Kennedy—for the tall, efficient-looking man in the gray suit and there would be instant focus: whispers, glances, gestures, timorous approaches, and hopeful self-introductions. None of this happens to George Bush; even in his own hometown, he is allowed to pick his way to the gate unnoticed. This would not have been so surprising—after all, how many would have recognized Jimmy Carter at this stage of the game four years ago—were it not for the fact that Bush can hardly be compared to a then obscure Southern governor. He has been a national political figure for more than a decade, the only Republican other than Reagan with such staying power. He has twice been oh-so-close to the vice presidency, and he has held more appointive offices than anyone this side of Elliot Richardson. He’s run two winning races for Congress and two losing races for the Senate. If politics were simply a matter of comparing résumés, the Republican nomination would already belong to Bush. But despite all the years of exposure, Bush remains the least known of all the leading contenders. Like a soldier with a superb battlefield record who is nonetheless passed over for higher command, he has captured everything but the imagination.

Bush’s chances were often downgraded during the initial maneuvering for the Republican nomination. His anemic ranking in presidential preference polls and low name recognition obscured his growing campaign treasury and his stature as almost everyone’s second choice. One usually astute Connally advisor, a Texan, said last summer that Bush was really running for vice president and brushed off his presidential ambitions with “Sure he’s a nice guy, but he’s got no more chance of being president than I do.”

But Americans choose their presidential candidates in strange ways. The nominee emerges not from a single national plebiscite but after fifty staggered regional contests, each with its own rules and issues and rewards. The race is not necessarily to the swift; indeed, the long campaign is not really a race at all but a decathlon where none of the contestants knows how the events will be weighted or scored. The advantage of such a process is that it gives dark horses like George Bush a fighting chance; the flaw is that the dark horse can turn out to be George McGovern—or, some would say, Jimmy Carter. “There may be a better way to elect a president,” Bush acknowledges, “but I can’t be for it. This way is my only chance.”

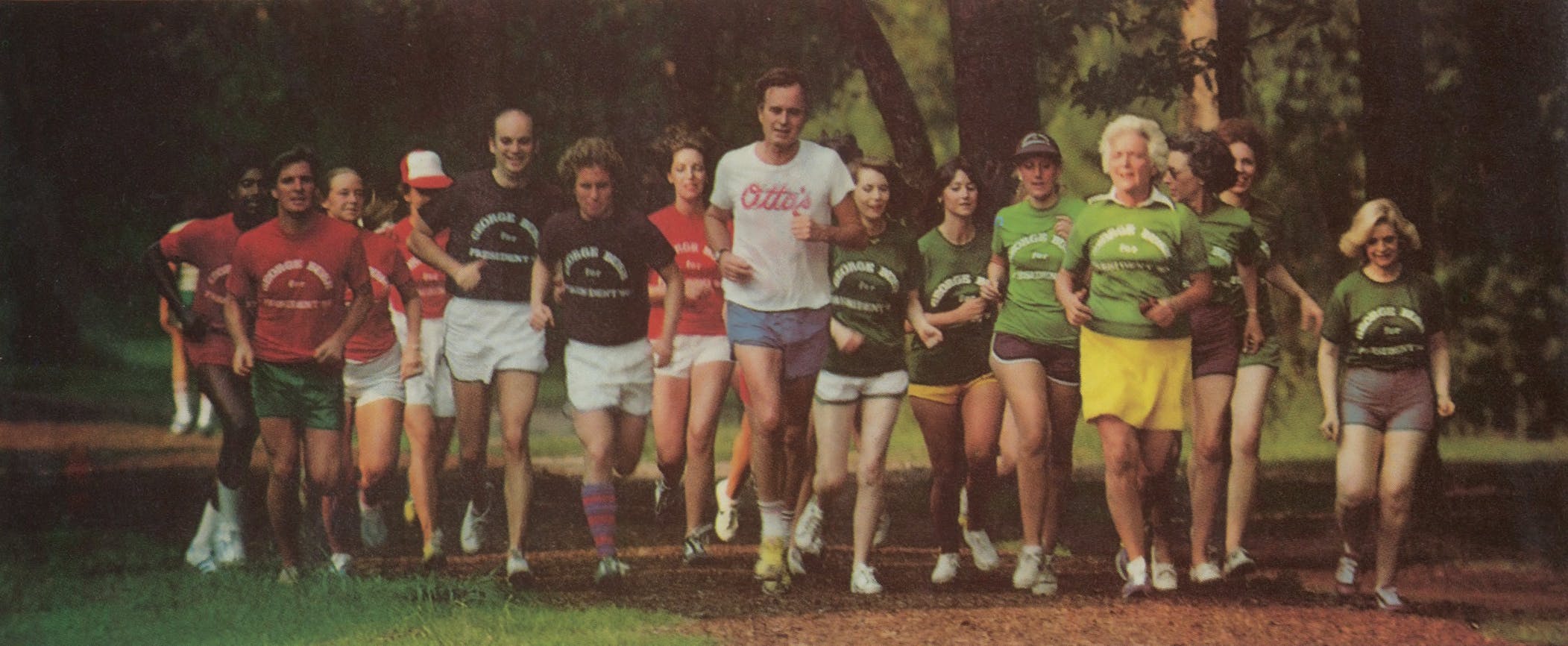

That chance, to sum up the Bush strategy, is to substitute organization and personal contact for name identification. After Bush lost his second senatorial race in 1970, it was said that he would have won if only he could have met every voter. In a race like the pivotal New Hampshire Republican primary, where the electorate and the geography are vastly scaled down from Texas, the goal is more than just a wistful hope. Fortunately for Bush, many of the small states will pick their delegates early—including Connecticut, where his father once served as U.S. senator, and Maine, where Bush has a summer home. Already he has won a straw vote in Maine and an informal poll in Iowa, another crucial early state. The first objective of every presidential candidate is to avoid getting blitzed in the first month of primaries; the schedule is so favorable to Bush that he can hardly fail.

So once again George Bush is assured of coming close. That has been his fate since his initial venture into politics in 1964, when he ran for the Senate against liberal Democrat Ralph Yarborough. Bush, then 39, was a little-known local party worker, first in Midland, where he had founded Zapata Petroleum Corporation, then in Houston. Though baselessly accused of being too liberal (sample enemy slogan: “Who’s hiding behind the Bush?”), he won the Republican nomination easily, and his combination of Kennedyesque style and Goldwater politics earned him instant recognition as a Republican hope for the future. But he had no chance to beat Yarborough: it was Bush’s ill fortune to enter politics in the year when Lyndon Johnson was at the top of the ticket and Texas Democrats were united for the first time since the thirties.

That was a sign of things to come. Bush has known more than his share of disappointment, bad luck, and even shabby treatment during his career in politics. They have plagued him at every stage:

- After losing the Senate race, Bush captured a new Houston congressional seat in 1966. His New Republican image was still so strong that it propelled him into vice presidential consideration in 1968, and the choices were down to three men, including Bush and Massachusetts Governor John Volpe, when nominee Richard Nixon, in a moment of perverse inspiration, chose Spiro Agnew.

- Bush left Congress in 1970 to meet Yarborough again, but Yarborough couldn’t keep the date. He lost to Lloyd Bentsen in the Democratic primary, and suddenly Bush faced not an unpopular liberal but a conservative Democrat in conservative, Democratic Texas. Once again luck had failed him.

- Looking for a consolation prize to keep him in politics, Bush let it be known he was interested in being Secretary of the Treasury. Instead, Nixon gave the job to John Connally, not only a Democrat, but also the person said to be most responsible for Bentsen’s victory over Bush.

- It wasn’t much consolation, but the prize Bush got was ambassador to the United Nations—a position that could hardly help him back home. Bush was instrumental in the election of current Secretary General Kurt Waldheim, but he lost the big one—keeping Taiwan in the UN when the People’s Republic of China was admitted. The defeat wasn’t Bush’s fault—he was undercut by his own government, for Henry Kissinger was sipping tea in Peking even as the vote was taking place in New York—but that didn’t stop a New York Post reporter from telling Bush afterward, “Well, that’s the end of your political career.”

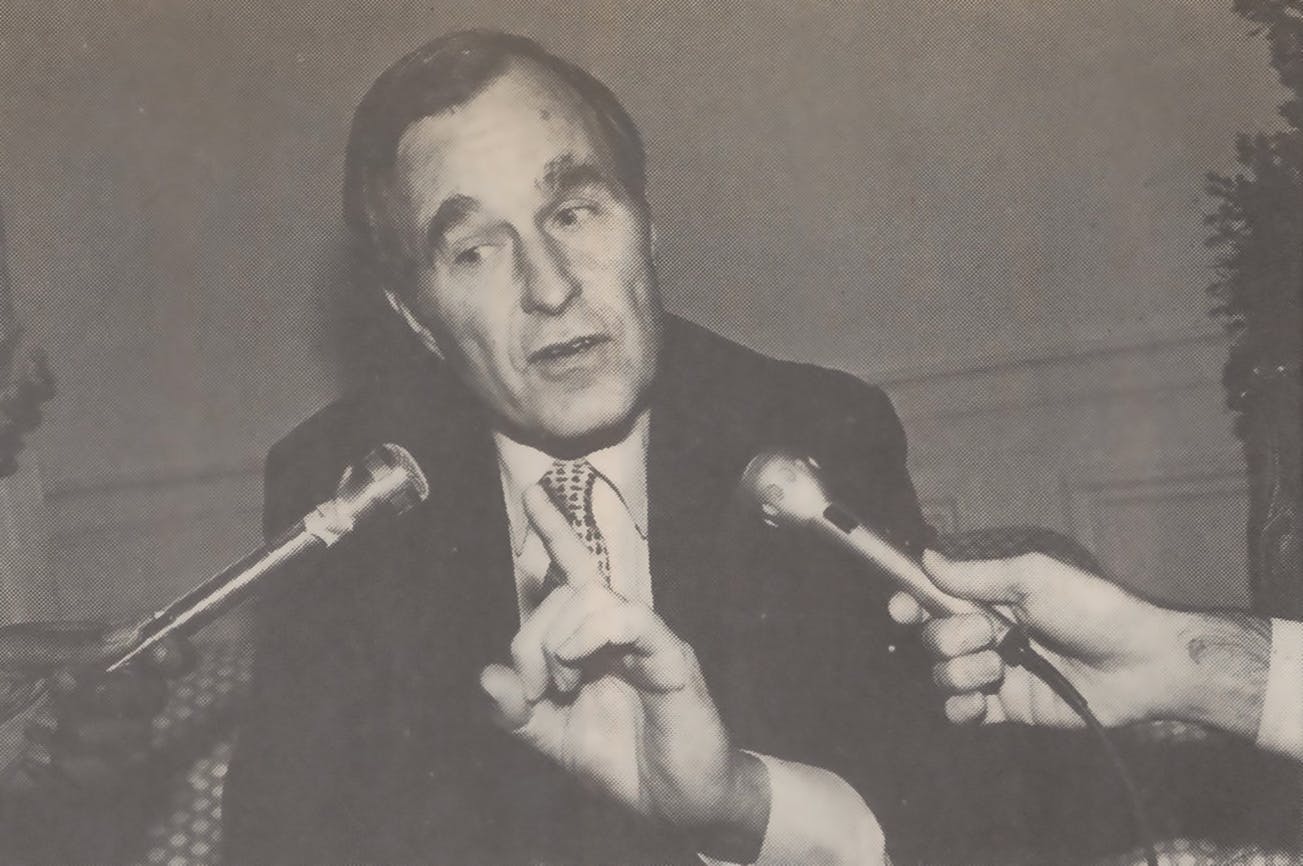

- In 1973, Nixon, already reeling from Watergate, asked Bush to become chairman of the Republican National Committee. Bush didn’t want the job: he didn’t want to defend the indefensible, and he didn’t want to be in charge of what was sure to be a rout in the 1974 midterm elections. But he took it anyway, out of a sense of duty. He went to every state at least twice, logged 200,000 miles, and did what he could to separate Watergate from the Republican party, but the 1974 defeat was worse than anyone had predicted. Once again Bush was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

- As one of the few visible Republicans whose credibility survived Watergate, Bush was a leading contender to become Gerald Ford’s vice president. He and Nelson Rockefeller were the two finalists, and again Bush came up short. It was the nadir of his career; he learned of Ford’s choice from a TV newscast.

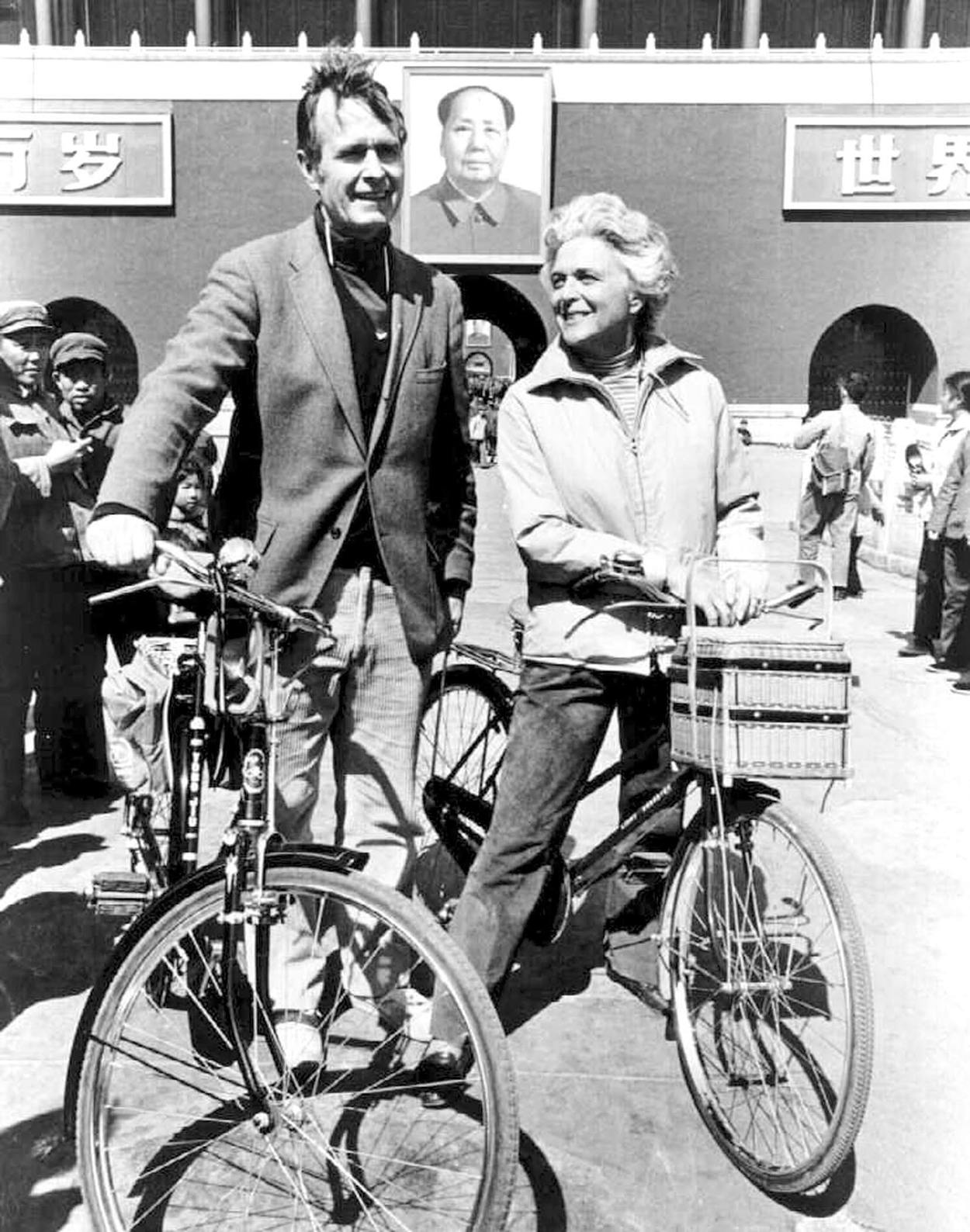

- Yet another thankless job awaited Bush. After a tour in China as head of the U.S. diplomatic mission there, he was called back to rejuvenate the embattled Central Intelligence Agency. It is exactly the kind of job calculated to drive an ambitious politician to despair: success is measured by how well you stay out of the news. Except for some memorable confrontations with Senate oversight committees, Bush stayed out.

It has been a long and often frustrating journey since that first senatorial campaign. At 55, Bush is no longer the Whiz Kid of the Republican party but seems to have become its Good Soldier instead. The new role has not been without its rewards—by speaking up for the party during its darkest days, Bush built up the contacts and the IOUs that have enabled him to assemble a national organization—but it also has its downside. A Good Soldier doing his duty is something less than a charismatic figure. Indeed, one of the essential elements of charisma is the presence of a tragic flaw—a potential, however slight, for malevolence. The very effort of overcoming it can make a Lyndon Johnson seem larger than life. Bush never seems to take on such expanded dimensions. Though his spirit seems remarkably undaunted by a career of near-misses, the disappointments and defeats have changed him. He is different from politicians with virgin egos: reflective rather than glib, restrained rather than dramatic. The difference shows up in small ways. En route to the airport that post-Thanksgiving Sunday afternoon, Bush tempered his damning assessment of Jimmy Carter—“He’s just not up to the job”—by adding, in an almost musing tone, “You know, I really thought he’d be a good president. I briefed him on national security and I was impressed with his grasp of it.” Most politicians would never give a rival that much credit, much less admit misjudging someone.

If there is fault here, it lies not in Bush but in an electoral system that places such a premium on image. But image can be manipulated, and it is up to Bush to convince people that perseverance, pensiveness, and probity are more to be valued in 1980 than whatever it is that the others are trying to sell. His early success seems to have dispelled the notion that he is just a nice guy running in a tough-guy year—in the wrong place at the wrong time once again. Maybe at long last George Bush’s luck is about to change. Says Houston lawyer Jim Baker, his national campaign chairman (and Gerald Ford’s in 1976): “Decency ought not to be a disqualification for the presidency.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- John Connally

- George H.W. Bush