Ed Lewis Ates spent twenty years in a Texas prison because of two lies, one snatch of hearsay, and one piece of human feces on his shoe that, when all was said and done, was never actually proven to be human feces in the first place. Though the evidence was remarkably thin, prosecutors in Smith County—a conservative, law-and-order community ninety miles east of Dallas—brought Ates to trial twice. The first one, in 1996, ended in a hung jury. So they tried again two years later. This time they were successful, and Ates got 99 years in prison.

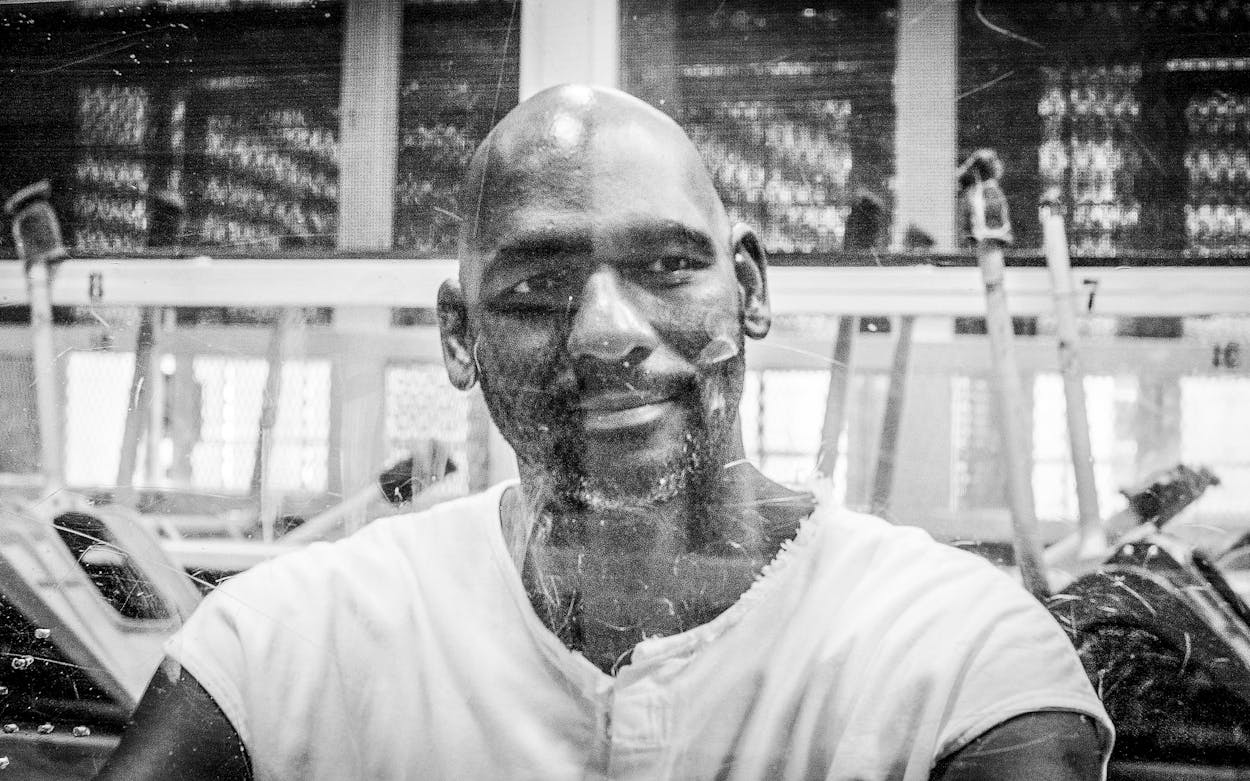

Ates, who is six foot six, bald, and 50 years old, is being paroled tomorrow morning and will walk out of the Walls Unit in Huntsville and into the arms of his wife, Kim, and his two grown children, Kyra and Zach. Kyra was two when her father was sent away; Zach was in utero. Also in attendance will be Ates’s attorney, Allison Clayton, who works for the Innocence Project of Texas, and four of her law students from the Texas Tech Innocence Clinic, who all traveled from Lubbock. Finally, Ates will be greeted by a man named Bob Ruff, a burly, tattooed podcaster from tiny Bridgman, Michigan. Ruff’s weekly podcast Truth & Justice has hundreds of thousands of listeners, and for the past two and a half years, he’s devoted many of his shows to the prisoner’s extraordinary story.

Ed Ates was born and raised in the rural community of Chapel Hill, just east of Tyler. He was arrested in August 1993 for the murder of Elnora Griffin, whose body had been found in her trailer on July 23. Law enforcement figured she had been killed the previous night. Griffin was naked, face-down on the floor. She had been viciously stabbed in the throat—a six-inch gash that went to the bone. Her tiny body (she was four foot four and weighed 104 pounds) had numerous cuts, bruises, and scratches. She also showed signs of having been grabbed by the throat, though not strangled. There was evidence of a terrible struggle: blood drops everywhere, and also what looked and smelled like feces in several spots on the floor, including the kitchen, where one splotch was smeared as if someone had stepped in it. The medical examiner would later say that a victim throttled by the throat might defecate uncontrollably. Swabs taken from Griffin did not show evidence of rape, though there was a semen stain on a comforter. One thing was clear: whoever did this would almost certainly have scratches on his or her own body—as well as bloody clothes.

None of Ates’s hair, blood, fingerprints, or semen were found at the scene. And when investigators questioned him later that night, he had no scratches or bruises on his body; they checked his hands and made him take off his shirt to be sure. There was no blood on his shirt, shorts, or shoes.

But four things made the police focus on him as a suspect: First, he lived near Griffin, with his grandmother Maggie Dews, who had mostly raised him. In fact, Ates, who did odd jobs for a living, had mowed Griffin’s yard just a week before her murder. Second, a friend and neighbor of theirs named Cubia Jackson told investigators that she had called Griffin that night between 9:45 and 10:30 and asked what she was doing. “I’m sitting here talking to Edward.” Edward who? “Edward Lewis, Ms. Dew’s grandson.”

Third, Ates lied about his alibi when investigators questioned him. (His mother was also present.) Ates denied being with Griffin and told investigators that his girlfriend had picked him up and taken him to her apartment between 9:30 and 10 p.m. and brought him back a little after midnight. But his girlfriend said that, although she had seen him that night, she in fact had not picked him up; he had shown up at her door and claimed he’d been dropped off by a friend.

The fourth thing: a possible piece of poo. During the interview, an investigator asked to check out Ates’s shoes, looking for blood. He didn’t find any, but he scraped off a little blob of something that he thought smelled like feces. Since Griffin had defecated on the floor and someone had stepped in it, Ates had now solidified his position as the number one suspect.

At his first trial, in 1996, the supposed bit of feces was used in evidence, even though an FBI serologist named Dick Reems testified that the only thing his testing revealed was that the material was “protein of human origin” (in other words, it could have been just about any substance from a body gunked up in some dirt or dust), and whatever it was, it couldn’t be linked to the victim. Still, prosecutors theorized that Ates killed Griffin, stepped in her feces, drove her car to his girlfriend’s, returned home after midnight, and lied about it to cover his tracks. They offered no apparent motive—Ates had no history of violence—and perhaps because of that, as well as the paucity of evidence, the jury got bogged down in deliberations and after two days still hadn’t reached a decision. At some point during this time, prosecutors approached Ates’s lawyers with a deal: plead guilty, take ten years. His lawyers told him he’d be out in three. Ates refused. “I said, ‘You got to be crazy,’” he remembered recently. “That would be admitting to killing her—and I didn’t kill anybody.” Finally, judge Louie Gohmert declared a mistrial.

Ates thought his nightmare was over, and he hoped that he could return to his quiet country life, especially because he had others depending on him now. There had been a long gap between his arrest and his trial, and in that period he had married a pretty young woman named Kim Miller. They had met at a Halloween party in 1994 and fallen for each other; the next day he called Miller—a sociology student at the University of Texas at Tyler—seven times. She liked him too. She swore he looked like Michael Jordan and wasn’t surprised to hear that he played basketball. What she liked most was that he was laid-back and quiet. When he told her that he was under indictment for murder and would be going on trial soon, Miller thought he was kidding. There was no way, she thought, that this guy was a killer. He was a gentle giant. The two began spending all their time together, and not long before the trial, they had a daughter, whom they named Kyra.

After the 1996 mistrial, the family moved to Dallas. The couple married and Ates drove a truck for a living. They bought a home. And he thought that he had finally put his troubles in Smith County behind him.

But in the summer of 1997 Ates began getting notices to appear in court in Tyler. The D.A. was preparing to try him again. So Ates began going back and forth between cities for docket calls while trying to hold down his job. Finally, when he missed a court appearance, he was arrested for violating his bond and put behind bars in the Smith County jail. Once again, prosecutors offered plea deals, and once again, Ates turned them down.

Finally, in August 1998, his wife five months pregnant with their second child, Ates went on trial again, with the same lawyers but this time in front of an all-white jury. Again, the state used as evidence Jackson’s hearsay and Ates’s lie about his alibi. They also directly asserted that Ates had human feces on his shoe, even though there was no science to back this up. In fact, in direct opposition to the FBI expert’s testimony that the substance was merely “protein of human origin,” one of the prosecutors told the jury, “The expert testimony from Dick Reem was…that was human feces.”

And this time the prosecutors had a secret weapon, a two-time felon and former cellmate of Ates’s at the county jail. His name was Kenny Snow, and he claimed Ates had paid him to lie and testify that someone else—another inmate—confessed to killing Griffin. Snow said Ates had even written out a script of a conversation between Ates and the other inmate and asked Snow to memorize it, but that Snow instead sent the script to the D.A. At trial, Snow, who was himself awaiting trial for two robberies, denied that he’d made any kind of deal with the prosecutors.

Again, the jury took a long time to deliberate over a verdict, but on the third day, it found Ates guilty. Miller, weeping, watched as her husband was handcuffed and taken away. Ates was hustled off to prison, ending up at the Coffield Unit near Tennessee Colony. Soon, his direct appeal was turned down. Ates got a lawyer to file for DNA testing in 2002, but no tests were ever done.

Video courtesy of Jared Christopher.

Five years later, Ates’s grandmother hired two Houston lawyers, Randy and Josh Schaffer, to take his case, and in 2010 they filed a writ of habeas corpus that was based mostly on the Snow testimony, which the attorneys alleged was a lie. Snow himself gave an affidavit in which he said his testimony was false—and that the conversation he’d actually heard between Ates and that other inmate involved the latter confessing to Griffin’s murder. Snow alleged that prosecutors told him if he helped convict Ates, he’d get probation, which he did: three months after Ates was convicted, Snow pleaded guilty to the robberies and received ten years probation, even though with his record, he was eligible for 25 years to life. Prosecutors denied any kind of deal—and denied everything in the affidavit.

The writ of habeas corpus was turned down. Ates, his last chance gone, fell into despair. He resigned himself to spending the rest of his life in prison. And he asked Miller to move on with her life, to divorce him and create a new life for herself—as well as a new family for his children. As a husband and a father, he was done.

A few years later, in 2014, a tall, bearded fireman in rural southwestern Michigan named Bob Ruff began listening to a true-crime podcast called Serial. Ruff, like millions of others, became obsessed with the deep dive into a 1999 murder in Baltimore County, Maryland—a messy case and a possible wrongful conviction. Part of the thrill was the episode-by-episode uncertainty; it was just like a real investigation. Ruff listened over and over and finally decided to start his own podcast about the case, which he called Serial Dynasty, and began picking up listeners who were drawn to his observations and theories. In October 2015 he renamed his podcast Truth & Justice, set up a GoFundMe account, and raised some money. With more than 100,000 listeners, in January 2016 he quit his job and became a full-time podcaster. Now he just needed a case to investigate.

One of his listeners emailed about her uncle, who she said was in prison in Texas for something he claimed he didn’t do. His name was Kenny Snow. Ruff began investigating and found that Snow, a former boxer, had done prison time in the early nineties, been released, and then been arrested again in January 1996 for two robberies. Two years later Snow testified against Ed Ates, helping send him away for 99 years. After Snow had been freed on probation, though, he had violated his parole and in 2004 been sentenced to forty years.

Ruff thought there might be something to Snow’s case and made a trip to Tyler to get court documents. And he spoke by phone to the inmate, who told him that he’d lied in his testimony about Ates. Snow couldn’t be certain that Ates was innocent, but he reaffirmed to Ruff what he’d said in the affidavit about hearing another inmate confess to the murder. Ruff soon realized that there wasn’t a whole lot he could do for Snow, who had pleaded guilty to those robberies.

But Ates was another matter. Ruff sent him a letter, and at first Ates didn’t respond. He didn’t trust people on the outside, especially those offering to help. He felt isolated from the free world; his grandmother had died and he hadn’t talked with his mother in a couple of years. Since he’d told Miller he wanted a divorce, she had retreated from him as well and only visited once a year, on Father’s Day, bringing their children.

Ruff mailed Ates another letter, and this time the inmate wrote back. Soon Ruff got him on the phone, and found himself liking Ates, who didn’t hype things or badmouth others, even though he had plenty of opportunity to do so. Ates seemed honest and kind. Ruff was perplexed—could Ates really have viciously killed Elnora Griffin?

The more Ruff talked to Ates and the more he read about the trials, the less he thought so—which he told his audience, week after week. In March Ruff aired his first interview with Ates, and he also began talking with Mike Ware, executive director of the Innocence Project of Texas, about Ates’s case. IPOT prides itself on taking cases in which the inmate genuinely appears to be innocent, and Ware said he’d be happy to look into the case, but he needed trial transcripts and exhibits. So Ruff traveled to the Smith County courthouse with a portable scanner given him by a listener; it made copies of transcripts, twenty pages at a time. It took him five days. He shared many of the documents as well as crime scene photos on his website.

On Truth & Justice, Ruff had initially laid out the prosecutor’s thin case against Ates, but he soon found himself devoting every episode to reinvestigating it and giving Ates’s side of his story. Ates told Ruff why he had lied about his alibi: he had borrowed his grandmother’s car that night to visit his girlfriend, something he wasn’t supposed to do and didn’t want his mother (who sat next to him in his two interviews) to know. And that was for good reason: Ates’s mother had shot her two former husbands and would later shoot Ates’s brother (all survived). “He wasn’t worried about the cops,” said Ruff. “He was worried about his mother.”

And Ates told Ruff that the “script” Snow testified about was actually a page of notes he had written up about what the other inmate had told him. Ates said that one day the notes (which he’d planned to give his lawyer) vanished from the cell and he never figured out what happened to them, though he later realized Snow had taken them. In one of Ruff’s conversations with Snow, Ates’s former friend recorded a message, which the podcaster read to his listeners: “I would like to tell Mr. Ates that I’m sorry for what happened. Wrong is wrong and right is right so when it happened, I knew I had to make it right…If I can help in any way I can, I will be at peace with myself.”

The Ates case was becoming more and more popular, and Ruff had listeners calling in to help in the investigation, offering tips and feedback. Ruff would ask for assistance on Twitter and Facebook; listeners would respond there, via email, or even by phone. A serologist looked into the data from the 1993 blood typing. Amateur photo experts tried to discern a footprint in the kitchen feces stain clump. When Ruff needed help figuring out who had a certain unlisted phone number, a volunteer in Tyler went to the city library and pored over old phone directories. When Ruff needed help figuring out what time the show Unsolved Mysteries was playing the night of the murder, since that was the time Ates’s girlfriend said he came over, a listener who worked in a library with old microfilm of TV Guide looked it up. When those listings showed the hourlong show in a 30-minute slot, the actor Jon Cryer, a fan, told Ruff that he knew someone at the Lifetime network who could help.

In May the IPOT agreed to take the case, and Ates got a new lawyer, Allison Clayton, who began visiting and writing him. She had her students at the Texas Tech Innocence Clinic drive to Smith County to get more documents. Usually IPOT has to scrape together funding for its investigations to pay for things like experts and DNA testing. But now the group had what Ruff called his “Truth & Justice Army” to do that; in fact, when he put out a request for help to pay for possible DNA testing, listeners ponied up $7,000.

A month later Ruff got in touch with Kim Miller. “I believe your husband is innocent,” he said, and Miller could barely comprehend what she was hearing. This was the first time she’d heard anyone outside her family say that. She told Ruff that, although she’d agreed to divorce her husband, she still hadn’t filed the papers. Something had held her back. Now she went to visit him again and found a different person. He was no longer angry, no longer alone in his fight. And he was really happy to see her.

Her first question to her husband was “Can you forgive me?” Of course, he replied. Ates wanted his family back.

And he wanted to come home. Ates became eligible for parole in May 2012 and twice went through the process, but both times failed. To get parole, an inmate must show some kind of remorse for his crime and take responsibility for it—as a sign he is on the way to rehabilitation. Both times Ates refused, saying he wouldn’t cop to something he didn’t do.

He became eligible again in March of this year, and this time he had help. Ruff put out the call for listeners to send letters, and they flooded him with hundreds of them. He winnowed the stack to fifty and sent them to Clayton, who passed them on to the Board of Pardons and Paroles. Ruff sent his own letter about Ates. “He is a kind and gentle man,” Ruff wrote. “Edward is in no way a threat to society, nor was he ever.”

Clayton also hired parole lawyer Roger Nichols, who had worked six years for the board before becoming a parole attorney in 2009. Nichols read the court documents, looked at Ates’s prison record (he had worked numerous jobs, including cook and tractor driver), and listened to some of Ruff’s podcasts, then interviewed Ates. “I have pretty good instincts,” he said. “I met Ed, and I am absolutely convinced he didn’t commit that murder. He had a graceful, dignified manner that belied any notion he could commit a crime like that.”

The Texas parole system is an arcane one, with no formal hearings but opportunities for interviews with board members and parole commissioners; ultimately, Ates needed the approval of the three men in the Palestine board office. Nichols presented the case to one commissioner on March 27, and another interviewed Ates the next day. Ates later said he thought it went well (“I had a pretty good feeling about it”), even though, as at previous interviews, he’d refused to accept responsibility for the crime. The second commissioner then made his recommendation and passed the case to the third.

The process usually takes two to three weeks, but Ates was granted parole the very next day.

After he walks out of prison tomorrow, Ates’s family will take him home to Dallas, where he will wear an ankle monitor and live under an entirely new set of rules and restrictions. He’ll have some help from Ruff, who last month told listeners he had set up a GoFundMe to help ease Ates’s move back into the free world. As of press time, the fund had raised an amazing $34,000. And when Ruff announced that he’d like to help get Ates some kind of bargain on a used car, a listener said she knew someone at a Dallas dealership and reached out to him. The man turned out to be a fan of the Truth & Justice podcast. He told Ruff, “We’re not just gonna give him a deal, we’re gonna give him a truck!” As of tomorrow, Ates will own a white 2013 Dodge Ram 1500 pickup. Also as of tomorrow, Ruff’s Truth & Justice will join a series of other true-crime podcasts (Serial, Empire of Blood, In the Dark) that have successfully drawn attention to the cases of men who might have been wrongly convicted.

However, even Ruff knows that the next step—exoneration—is not going to be so easy. Exonerations take a long time, even when backed by an army of Innocence Project lawyers and well-intentioned podcast listeners. Clayton began the process last year, when she reached out to Matt Bingham, the current Smith County D.A., to see about getting some DNA testing on old evidence. To her pleasant surprise, Bingham was open to the move, and in December, IPOT and the D.A.’s office filed a joint motion for DNA testing of twenty items from the crime scene, including scrapings from underneath Griffin’s fingernails as well as the rape kit swabs. Clayton would also like to test crime scene fingerprints that were never fully analyzed back in 1993; they might give results in the modern Automated Fingerprint Identification System and the Multimodal Biometric Identification System. And she has plans to file a subsequent writ of habeas corpus under the state’s 2013 “junk science writ” that allows defendants to challenge convictions based on antiquated or specious forensic science. Clayton would like to debunk the state’s feces theory once and for all—and exonerate Ates while doing so.

Recently, Ates was asked how it felt to be getting paroled. “It’s a good feeling, but it’s not all the way there yet,” he said. “Parole is good, don’t get me wrong…but it’s not the same as being exonerated. I get to go home and be with my family, but that’s not what I want. I want my name back. I want this mark off of me, this stripe off of me.”

- More About:

- Crime