I.

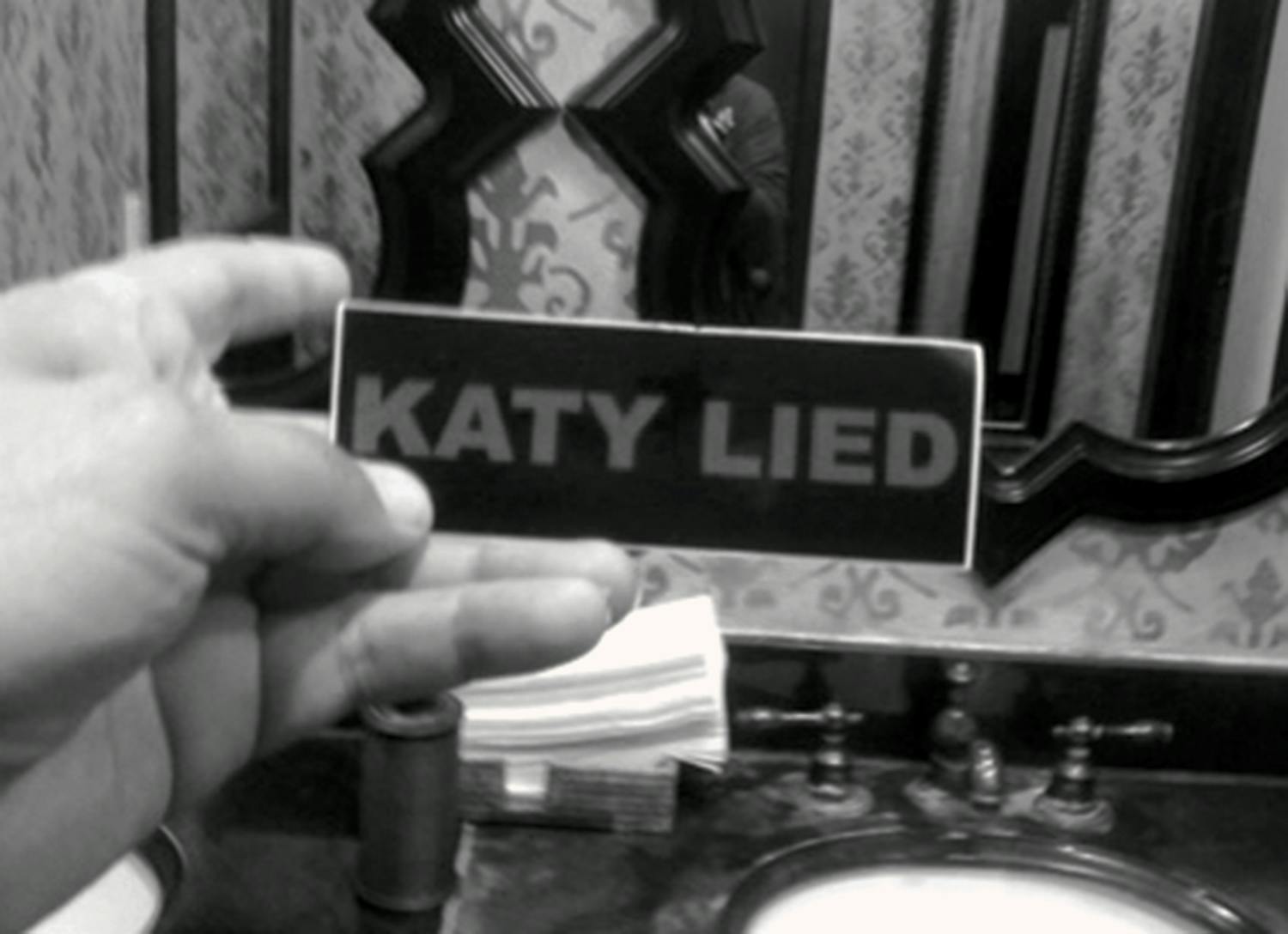

The black stickers started cropping up around Terlingua that fall. They all repeated the same simple phrase, in red capital letters: KATY LIED. Several appeared on a pump at a gas station in the tiny, far West Texas town, another was slapped on the back of someone’s truck, and one was even spotted in the bathroom of a bar about eighty miles away in Alpine. KATY LIED, KATY LIED, KATY LIED.

Everyone in the former ghost town of 110 full-time residents knew who Katy was: Katy Schwartz, a 36-year-old former model with brilliant green eyes who in July 2019 had told the Brewster County sheriff’s office that one of the most prominent men in Terlingua, an entrepreneur named Jeff Leach, had pinned her down and attempted to kiss her. The backlash was swift.

Schwartz started getting messages on Facebook. A friend sent her a photo of five stickers taped to a wall in what appeared to be one of the vacation rental properties owned by Leach, the same properties Schwartz had helped him manage as his employee and close friend. Not long after, a neighbor sent Schwartz a photo of one of the stickers placed on someone’s bare butt cheek. “You’re dead in this town,” the woman wrote to her. “You lied. We all know.”

In a place as small as Terlingua, it was impossible for Schwartz to avoid those who believed Leach when he said Schwartz was lying, that the encounter had been consensual. Many of Schwartz’s friends in town turned on her. One night, she says, a formerly friendly bartender at the Starlight Theatre, a local bar and restaurant, refused to serve her. Another night, a woman dumped a glass of water into her lap. “I wanted to smack her in her smug little face,” the woman later wrote on Facebook. Then, on September 11, 2019, Leach sued Schwartz for defamation. The ensuing comments on social media were cruel and pointed; some baselessly accused her of sleeping with the judge presiding over the lawsuit and of being an absent mother. Schwartz thought about deleting her Facebook account but eventually decided to keep it active so she’d know what people were saying about her. All around her was the vast, empty desert of Big Bend. She’d never felt so lonely.

This was not what she had imagined when she moved to West Texas from Los Angeles two years earlier, seeking some form of serenity and rejuvenation. For most of her life, she had been itinerant. When she was young, her family had moved around a lot, relocating from Texas to Florida when she was six. Her modeling career had started when she was ten, and her teen years saw her traveling the world for gigs. Schwartz hoped to experience a typical senior year complete with a prom, but she struggled to adjust to the conventional, confined environment of high school.

When she was eighteen, she dropped out and moved to New York, where she worked full-time for a major modeling agency and hung out with older models and celebrities—the “big shots,” as she would later call them. After her career abruptly ended, she resettled in Los Angeles. At nineteen, she became pregnant, drove with the father to Las Vegas for a quick wedding—Schwartz wore a T-shirt and jeans—and, five years later, got divorced. She shared custody of her daughter with the father. For years, she worked odd jobs, from waiting tables to booking gigs for a valet parking service to managing the office of a mom-and-pop air conditioning company. She eventually translated her love of cooking into a steady stream of private chef and catering gigs. That kept her going for a bit. But she longed for something different, a new start.

Then one day in May 2017, a childhood friend of Schwartz’s messaged her on Facebook with a job offer. Would she want to sign on as the head chef of a wine bar he was planning to open in a little town called Marfa? Though Marfa had gained national renown as an oasis for artists and celebrities, Schwartz knew next to nothing about the place. That suited her just fine—she was ready for a change. Plus, she’d spent part of her childhood in Lewisville, a suburb of Dallas, and she had an affection for Texas. Ten days after visiting Marfa, Schwartz packed her belongings into her Toyota Camry and headed east on Interstate 10.

Schwartz was eager to find her place in her new community. She volunteered to help provide meals to seniors at the Marfa Nutrition Center, and she painted an Instagram-popular “Greetings From Marfa, Texas” mural on the exterior of a coffee shop downtown. Her daughter, now a teenager, frequently came to visit and loved the town’s artsy aesthetic. But Marfa was expensive, and the chef job didn’t pay very well. After about nine months, Schwartz made her way to Terlingua, a historic town just over a hundred miles to the south that had fallen on hard times after its quicksilver mine played out in the forties, only to be reinvigorated in recent decades by an influx of tourists, artists, desert rats, and off-the-gridders. It took just a couple visits for Schwartz to fall for Terlingua’s quirky residents and the simple, rugged life the place seemed to offer.

Terlingua represented a stark departure from Marfa. While Marfa has become a pricey paradise for hipsters and high-end hoteliers, Terlingua has managed to retain most of its offbeat charm. Every November, tourists fill the streets, many of them unpaved, for the town’s chili cookoff (no beans allowed), and peculiar roadside art installations—a metal insect, a submarine conning tower stuck in the ground.

In many ways, Terlingua is exactly what you’d expect a former ghost town to be. Scattered across the sun-scorched earth are frames of empty adobe buildings, some reduced to nothing more than dusty masses of rubble, remnants of the hardscrabble community that had once settled around the mine. There’s a jail turned public restroom, a restored church, and a cemetery, its graves marked by crude piles of stone beneath wooden crosses knocked off-kilter by wind and time.

Less expected are Terlingua’s more modern attractions: its bars and restaurants, a proliferation of chic short-term rentals, and a bustling coffee shop with desert views from its patio. An affordable gift shop occupies what used to be the Chisos Mining Company’s commissary, alongside a hotel that prominently features its website on its sign (“Unexpected luxury in the Terlingua Ghost Town in the shadow of the Chisos Mountains, where great stories begin,” the home page advertises). There is, of course, Wi-Fi.

It’s not a particularly wealthy place. Most jobs pay minimum wage, and some residences don’t have running water or electricity. But in recent years Terlingua has seen an explosion of tourism, and the short-term rental business has grown exponentially—sometimes to the chagrin of longtime residents who moved to the outskirts of society for peace and quiet, not to suffer through loud Airbnb parties.

Jeff Leach is a driving force behind that change. His properties seem to be in a constant state of construction and expansion, and he’s one of the area’s major employers. Stickers plastered across town display catchy taglines, such as #NotLikeMarfa, that promote his rentals on social media.

It was impossible for Schwartz not to cross paths with Leach. A stocky, charismatic man with a background in biology, the 52-year-old Leach had been living in Terlingua for about three years, captivating locals with stories of conducting research into the diet of the Hadza people, in Tanzania, by examining the microbes in their stools. Leach claims to have used a turkey baster to transplant feces from one man into his own gut to see how it would affect his digestive system. The Hadza called him “Dr. Shit.” By the time Schwartz and Leach met, he was in the early stages of constructing Basecamp Terlingua, a mix of glamping-style tepees and sleek, igloo-like “bubble tents,” which afford guests unobstructed views of the starry night skies. (Basecamp was featured on the cover of the June 2019 issue of Texas Monthly as part of a story about new and improved Texas hotels.)

Schwartz soon became good friends with Leach’s girlfriend, Anna Oakley, and fell in with his close-knit inner circle. Leach offered Schwartz a job at Basecamp: first, doing manual labor and maintenance on his properties, then handling reservations, until eventually he made her his personal assistant. Schwartz was impressed by Leach, who spoke to multiple people about the doctoral degrees he had earned and the globe-trotting research he had done for the Human Food Project, a nonprofit he founded to study how diet affects gut health. The three friends began to travel together abroad on Leach’s dime: he was well known around town for his financial generosity, including high wages, at least by Terlingua standards (Schwartz was earning $15 an hour at Basecamp). According to Schwartz, Leach even offered to let her use his greenhouse so she could grow food to help feed senior citizens in Terlingua. During her L.A. malaise, this was the kind of life she had dreamed about.

But as Schwartz would later testify in court in response to the defamation suit filed by Leach, there were signs that Leach was not what he seemed. In an affidavit, Schwartz said she had heard rumors about Leach beating up an ex-girlfriend. Worse, a coworker told her that another woman, Helen Thompson (a pseudonym), had claimed Leach had raped her. But Schwartz didn’t know either woman, and people close to Leach dismissed them as “crazy” exes.

“I brushed it all under the rug because I didn’t believe it,” Schwartz said. “He was doing so much good work for the world, and for me personally, that there was no possible way he was capable of doing any of those things.”

On May 21, 2019, the night before Oakley and Schwartz flew to Puerto Rico on a Leach-funded jaunt, the three friends were hanging out at Oakley’s home, a retrofitted school bus. After Oakley went to bed, Schwartz said, Leach told her that Oakley wanted to have a threesome and that the couple fantasized about Schwartz when they had sex. Schwartz told him she was open to the idea as long as Oakley was okay with it—but according to Schwartz’s affidavit, Oakley woke up, heard them talking, became upset, and told them she had not wanted a threesome.

The incident made Schwartz uncomfortable, and the feeling lingered for weeks. Not only were Oakley and Leach her best friends in town, but Leach was also her employer. After the Puerto Rico trip, Schwartz reached out to Leach, hoping to talk. “I just want you to know I’m really struggling over here,” she messaged him. “Not talking to you about that night and thinking you are mad at me this whole time has made me feel so stressed out and I’ve [had] a difficult time focusing on doing my job.”

Leach replied, “Of course I’m not mad. Just a bit confused—was blindsided—but we r all good—we will all b fine.”

Leach messaged Schwartz two weeks later, inviting her over to talk about what had happened. Wearing her favorite summer outfit, a long white dress with blue flowers, she drove to Leach’s place, which she describes as a small, spare house at the end of a steep and winding dirt road. Oakley was out of town for Lasik surgery, so it was just the two of them, and they chitchatted about work while Schwartz used her laptop to take care of some reservations for Basecamp. Leach offered Schwartz a drink, and they moved outside to the porch, where they sat on a tattered couch and talked. She figured Leach had invited her over so that he could apologize in person. Night fell, and the lights from Study Butte were far-off dots in the pitch-black sky. Schwartz’s dog, Banjo, was out in the desert, exploring.

“I BRUSHED IT ALL UNDER THE RUG BECAUSE I DIDN’T BELIEVE IT,” SCHWARTZ SAID OF THE RUMORS SHE’D HEARD ABOUT LEACH. “HE WAS DOING SO MUCH GOOD WORK FOR THE WORLD, AND FOR ME PERSONALLY.”

Leach has denied parts of Schwartz’s account of what happened next. According to the police report Schwartz filed and her sworn affidavits in Brewster County district court, Leach began to talk to her about how he was confused about Oakley’s desires, that he thought she did want the threesome. Then he pinned Schwartz down on the couch and tried to kiss her. Leach told Schwartz he wanted her and that he “gets what he wants.”

As she recounted later in interviews with Texas Monthly, as Leach was allegedly straddling her and holding her down by her shoulders, it felt to Schwartz as though time slowed down, and all the bad things she’d heard about him in the past, the allegations of sexual violence, hit her like a rolling wave. “Oh my God,” she thought, “he’s trying to do this to me right now.” Because her hands were free, she managed to struggle against him and, after a few moments, push him off. Schwartz ran to her Jeep, one of the Basecamp company vehicles, called for Banjo, and drove off. (Leach later denied that he forced himself on Schwartz and said that they had instead just consensually kissed—which he claims Schwartz initiated—before she left. In legal pleadings, he has argued that Schwartz lied about what happened that night because he was her best friend’s boyfriend.)

Still in shock, Schwartz knew she didn’t want to be home alone, so, as though on autopilot, she drove to the Starlight Theatre, a place where she’d always felt safe. Schwartz sat on the porch with Banjo and had a few drinks, hoping it would help her sleep.

She began to question her emotions. “Was it as serious as I thought? Am I making a bigger deal out of this than I should be?” Then she flashed back to 2002, when she’d been an eighteen-year-old model in Manhattan. One morning, after spending the previous evening at a high-end club, she awoke in her apartment, battered and bruised, with little memory of how the night had ended. She completed a rape kit at the hospital, and surveillance camera footage from the club later showed that a bouncer had left with her that night, according to Schwartz and her mother, who said she flew to New York to be with her daughter following the alleged assault. The two went to the police, but the case was dropped. Schwartz never knew what happened to her rape kit.

(Historically, the New York Police Department has failed to properly investigate many cases of rape and sexual assault. In 2017 the NYPD said it was looking into the testing status of more than 42,000 rape kits dating back to 1980. The NYPD did not answer questions about the investigation into the alleged sexual assault or the status of Schwartz’s rape kit.)

Her friends didn’t believe her, and her agency promptly cut her loose. “I would see people on the street, and they would pretend they didn’t know who I was,” Schwartz told Texas Monthly. Her modeling career was over.

She soon left New York for Los Angeles, but the trauma followed her. She began to self-medicate with alcohol to keep the memories at bay. “I stuffed it down,” Schwartz said. “I felt like I had to, because when it happened, I was abandoned and no one believed me—not the police, not my friends.” Now, in Terlingua, she was suddenly facing the same difficult choice: stay silent or speak up.

II.

A little before nine-thirty that night, Leach messaged Schwartz on Facebook.

“I wish u hadn’t left,” he said.

“I know. Shit ain’t right though,” Schwartz replied.

“Or maybe just right. U should come back. We never get this opportunity. We don’t have 2 f—.”

“I’m not coming back,” Schwartz said.

Two days later, while they were messaging about work issues, Schwartz confronted Leach about that night. Leach wrote that he’d been drinking and had a fuzzy memory.

“So you don’t remember pinning me to the couch and me having to push you off of me and leaving?” Schwartz replied.

“Kinda,” Leach said. “What r u pissed about?”

When Schwartz replied to clarify that she was pissed about Leach “trying to f— me behind my best friend’s back while she was having surgery,” Leach questioned why she hadn’t acted angry the day before when the two messaged and met briefly in person. “What’s different today? Don’t remember trying to f— u,” he said.

“Wut?” Schwartz responded.

“This entire thing between u, me and Anna has gotten all screwed up—much of it I’m confused by,” Leach wrote back. “Anyway best not to go near this in the future—I’ll do my part. And I apologize if [sic] for the other night—won’t happen again. Again I’m not really clear on everything from the other night but I take your word for it.”

Over the next several days, Schwartz confided in multiple people. First, she told Oakley, who Schwartz said became “livid” and confronted Leach over Facebook message. Leach allegedly responded to Oakley by saying that he planned to hire an attorney. Then Schwartz told multiple coworkers, including the operations manager at Basecamp, that Leach had forced himself on her. “I was alarmed when I heard the story,” the manager said later in an affidavit (the manager no longer works at Basecamp and requested anonymity because of restrictions about speaking to the press at the manager’s new job). “I was surrounded by crying employees and trying to remain calm.”

Meanwhile, according to the manager’s affidavit, Leach had been sending employees a flurry of work-related messages, including telling the manager that Schwartz had been demoted.

By July 1, Leach announced that he was going on an international trip. “I’m headed to Canada,” he messaged the manager, who shared copies of the Facebook messages with Texas Monthly. “Back in a few days.” Schwartz was still unsure if she should tell the police what had happened. She worried that the fallout would hurt Oakley in particular.

Being alone in Terlingua was an unnerving prospect for Schwartz. The nearest hospital was eighty miles away in Alpine, and the nearest domestic violence shelter was sixty miles away in Presidio. And despite its reputation as a redoubt for mavericks, the town had many residents who liked things just as they were. If high-profile women in the media and Hollywood had suffered a backlash after coming forward with allegations of sexual assault, Schwartz thought, then surely the retaliation would be even more intense in a place as remote and isolated as Terlingua. “I didn’t know what to do,” she said. “Part of me was like, ‘Just hold it in.’ ” Still, Schwartz wondered, what if there were more women? What if others hadn’t been able to fight Leach off?

On July 3, Schwartz walked into the Brewster County sheriff’s office. “Schwartz reported she only wanted this incident documented,” the police report said. Schwartz said later in an affidavit, “I was too afraid to press charges, but I wanted to put it on the record because the incident made me realize that the other rumors about assault by Jeff Leach were probably true, and I wanted to protect myself and others.”

After filing the police report, Schwartz stayed with a friend in Alpine for a few days, then flew out of state for an extended vacation with her parents. She badly needed a break. Meanwhile, a storm was brewing in Terlingua. Leach returned to town and sent a Facebook message to several of his Basecamp employees announcing that he would be suing Schwartz for “making false statements to law enforcement and the general public” and “for other false or misleading statements with intent to harm.”

When Schwartz returned to Terlingua at the end of July, she learned that several Terlinguans who’d initially supported her when she first came forward, including Oakley, had since switched their allegiance to Leach. At the Starlight Theatre, a bartender berated her. “She said how dare I come in there, that I’m a liar,” Schwartz said. “Just screamed at me in front of everybody.” (In an emailed statement, a representative for the Starlight said she had “absolutely no knowledge, nor comment about Ms. Schwartz or Mr. Leach.”)

But Schwartz’s visit to the sheriff’s office had had another effect. That same day, Helen Thompson—the woman a Basecamp colleague of Schwartz’s had told her about months earlier—heard about Schwartz’s account. The next day, July 4, Thompson gave a statement to a Brewster County sheriff’s deputy alleging that Leach had assaulted her in 2014, after a consensual sexual encounter had turned violent. (Leach has denied the allegations, claiming they had consensual sex and that Thompson “never expressed any complaint to me that it was not consensual before the sex, during the sex, or any time after the sex that night.”)

The community seemed to divide into two warring factions: those who believed the women and those who believed Leach. Oakley made clear that she was taking Leach’s side. “I don’t believe that all men are rapists and I don’t believe that all women tell the truth,” she wrote on her Facebook page. “Everyone has suffered in some way from Hurricane Katy.”

Then, in early September, Leach filed the defamation lawsuit against Schwartz, inflaming his supporters even more. But over the next few months, two more women would come forward with allegations of sexual misconduct against Leach. Would they too face the same public derision as Schwartz? Would the authorities seek justice or brush them off?

III.

The small size of communities like Terlingua makes it particularly difficult for survivors of sexual violence to seek help or speak up without the entire town finding out. Gina Wilcox, the program coordinator and advocate at the Family Crisis Center of the Big Bend, which serves five counties across about 20,000 square miles, told me that women seeking help will park down the block from the crisis center in Alpine, rather than across the street, to avoid being spotted there. “Everybody knows what’s going on in your life, sometimes before you do,” Wilcox said, speaking generally about the cases she sees in those small towns. “If you do make something public, it becomes fodder for the rumor mill. A lot of survivors, they’re embarrassed by that, so they hesitate to report.”

One of the women who came forward, Alaine Berg, had also been part of Schwartz and Leach’s social circle. Berg, who grew up in a North Dakota farming family, had been close friends with Oakley for nearly a decade, and Berg and her husband would frequently host get-togethers at their house, in a small town about a hundred miles northeast of Terlingua. According to Berg’s affidavit, one night in May 2018, while a group was hanging out in Berg’s backyard, Leach slid his hand all the way up her shorts and touched her without her consent. It was dark, and according to Berg, no one else noticed. She got up and sat next to her husband. “I froze because no one has ever done that to me,” Berg told Texas Monthly. “Everybody says, ‘Alaine, why didn’t you punch him in the nose?’ It was just too shocking to me. There were people there. He’s intimidating, powerful. I just didn’t know how to react.” (Leach has denied that he touched Berg.)

The next day, Berg told her husband what had happened, and they discussed what to do. Their friendships were at stake, and Leach had never done something like that to her before. They decided to let it go. But when Schwartz made her allegations, Berg reconsidered going to the police. By then, she had heard rumors of other victims too. She talked it over with a lawyer, her therapist, and a counselor at the Family Crisis Center of the Big Bend. On September 10, Berg filed a police report with the Brewster County sheriff’s office. Two days later, she received a cease-and-desist letter from Leach’s attorney, Rae Leifeste, threatening her with a lawsuit seeking “all legal damages and costs of court” if she continued to talk about what had allegedly happened.

In November, the Big Bend Sentinel reported that Lisa Anderson, another of Leach’s exes in Terlingua, had in 2017 obtained a temporary restraining order against him that barred him from coming within five hundred feet of her residence. (Lisa Anderson, whose name is a pseudonym given to protect her identity, has not filed an affidavit in Schwartz’s defamation lawsuit.) Anderson and Leach had dated for three tumultuous years. On three occasions, according to police and court records, Leach allegedly turned violent during an argument. In September 2015, Anderson called the police, alleging that Leach had grabbed her and “shoved her around” before leaving.

But the responding deputy said Anderson was uncooperative when he tried to get information out of her. “She was extremely evasive, and made it clear from her answers that she didn’t want to get Leach in trouble and was trying to protect him,” the deputy wrote in the incident report. “I determined Leach to be the aggressor, and placed him under arrest.” Leach was ultimately released, and without cooperating witnesses, no charges were filed—a frequent occurrence in domestic violence cases. In a Facebook comment beneath the Brewster County sheriff’s office post detailing the arrest, Anderson wrote that it was a “misunderstanding” and said the deputy “overreacted.” (Leach later said Anderson was drunk and yelling at him. He claims he was arrested after Anderson and her brother physically restrained him from retrieving his laptop from Anderson’s house.)

According to Wilcox, there are many reasons why a victim of domestic abuse might not speak out or seek help. “Most victims are concerned about retaliation and repercussions within the community, and not always retaliation from the abuser themselves. Sometimes it’s from their friends or family or people who are supporting the abuser or the perpetrator,” she said, speaking generally about the cases she sees.

During a trip to France the following year, according to screenshots of messages between Leach and Anderson that were included in court documents related to the restraining order, Leach allegedly broke Anderson’s finger and tooth during an argument. “I seem to be the only person in the world you treat so badly,” Anderson messaged Leach. “You are physically, mentally and verbally abusive all of the time. Even when we were supposed to be having a romantic getaway in Paris together because of the last 4 months when you took off.”

“I apologized for that. And I am sorry I did what I did,” Leach replied. “It wasn’t right. And I know this. We were both hoping we could put this behind us and focus on each other and building our business and life. The shit is Paris in [sic] inexcusable and alcohol driven.” He also claimed that Anderson’s finger may have been hurt while he was trying to wrest a backpack from her.

Anderson was also Leach’s business partner in their bed-and-breakfast and boutique hotel company in Terlingua. Their breakup six months after the Paris trip resulted in a contentious legal battle over the business. Leach sent Anderson emails calling her a “c—t” and threatening to punch her in the mouth (the emails were quoted in court documents). As part of a mediated settlement agreement reached in October 2017, Leach was ordered to pay Anderson $110,000, most of it to be disbursed in installments. On the memo line of one of the checks Leach sent to Anderson, he wrote, “gold digging whore payment + f—ing mental anguish.” (A photocopy of the check was included in court documents.)

By June 2018, Anderson had left Terlingua and dropped her request to make permanent the temporary restraining order against Leach. In court filings, her attorney wrote that Anderson didn’t believe Leach would actually abide by another protective order and that she didn’t want to “further relive the ordeal of their relationship in pursuit of such an order.”

As Leach’s relationship with Anderson faded in 2017, he began a new relationship with Elizabeth Johnson, a friend of Anderson’s who worked as a bookkeeper for Leach’s rental company. (“Elizabeth Johnson” is also a pseudonym; she requested anonymity out of fear of retaliation for speaking publicly about Leach.) As she later said in her affidavit, Johnson knew that Leach could be violent—she said Anderson would sometimes visit her house in tears, confiding in her friend that Leach was grabbing and pushing her and throwing things. Johnson thought Leach “could really kill her eventually.” According to Johnson, when Anderson was out of town, Leach made advances toward her, even though she’d just gotten out of a long-term relationship, and managed to convince her that his behavior was Anderson’s fault. “He’s a predator,” Johnson said. “He took advantage of my being weak in that time. I just wanted someone to love and respect me and to be kind to me. And he did those things. He was kind to me.”

Then, one night in the summer of 2017, Leach allegedly penetrated her without her consent, according to an affidavit Johnson later filed in support of Schwartz’s defamation defense. “I felt like I was becoming an outlet for his anger,” she said.

After Johnson and Leach broke up, she became “super reclusive,” rarely going out in public. “I crawled into the deepest, darkest hole I could find,” she said. At one point, she confided to a friend that Leach wasn’t a nice guy and that he’d mistreated her. “He just kind of wished it away and said, ‘Oh, get over it,’ ” she said. “That only solidified my feelings that I should just keep my mouth shut and not tell anybody anything.”

In the months after Leach sued Schwartz for defamation, Johnson weighed whether she should come forward. She had seen the “KATY LIED” stickers around town and had heard people bad-mouth Schwartz and Berg. She thought it wasn’t right that Schwartz was being made out to be the villain. Johnson reached out to a mutual friend and told him to let Schwartz know that she would consider talking about what happened.

On a chilly day in late January 2020, Johnson was sitting at her booth at the farmer’s market in Terlingua. Schwartz walked over, introduced herself, and asked if they could talk. As they sat together on a couch, Schwartz started shaking with nerves, and her eyes filled with tears. She didn’t know what to expect from Johnson. All she’d heard about her was that she was another one of Leach’s “crazy” exes. Still, Schwartz had to ask: Would Johnson talk to her attorney, Jodi Cole?

Johnson readily agreed, and at the end of their conversation, the two women hugged. Johnson contacted Cole the next day and filed an affidavit in support of Schwartz’s defamation defense. She was the third woman to come forward with allegations of sexual misconduct in response to Leach’s suit against Schwartz.

“When I first heard about what was going on with Katy and the other women involved in this case, I wanted to reach out because I felt that I could make a difference by sharing my story,” Johnson said in the affidavit. “I had serious reservations though, because I am worried about Jeff threatening me with litigation, or physically harming me . . . I care about the other women involved in this case. Nobody should be treated that way . . . I don’t want to be afraid of him anymore.”

In defending Schwartz against Leach’s defamation suit, her lawyers argued that his reputation was so poor that nothing Schwartz said about him could cause him further harm. The allegations raised even more questions about Leach’s background and credibility.

IV.

Long before Jeff Leach arrived in Terlingua, he lived in a double-wide trailer in Austin while attending Westlake High School, located in one of the city’s most affluent enclaves. He was a good athlete, according to his half brother, Perry. Leach played on the storied Westlake football team, which has produced such NFL players as Drew Brees and Nick Foles. According to Perry, Leach’s parents, now deceased, were inattentive and allowed him to drop out of school his senior year. “I asked my dad, ‘Why’d you let him do that?’ ” Perry remembered. “And he said, ‘Well, he wanted to do it.’ Nobody put any restraints on him. He always got what he wanted, and there never seemed to be real consequences.”

It’s unclear whether Leach graduated from college. At some point, he moved to El Paso, developed an interest in archaeology, and began working as an archaeologist at Fort Bliss, where he helped preserve artifacts left behind by Native Americans who had lived on the land now claimed by the U.S. Army.

Colleagues there remembered him as charismatic and hardworking, eager to take the lead on projects—but, according to two of his former supervisors, he didn’t have the formal archaeology education that many of his peers did, and there were questions about the quality and ethical rigor of his research. One supervisor, Glen DeGarmo, remembered Leach as a “rogue employee,” and another, Galen Burgett, said his field work was largely unusable because he “didn’t know what he was doing.”

In September 1995, Burgett wrote a letter in support of a female colleague of Leach’s alleging that Leach had submitted a paper to American Antiquity, a scholarly journal, that plagiarized her work. “The individual in question is one of the most unscrupulous, dishonest, underhanded, scam artists I have ever had the misfortune of having to deal with in my 15 years as a professional archaeologist,” Burgett wrote. (The letter does not name Leach, but Burgett confirmed to Texas Monthly that he was referring to Leach. Neither Leach nor his attorney responded to requests for comment about his time at Fort Bliss.)

In 2000, after his stint at the Army base, Leach started a monthly archaeology and travel magazine called Discovering Archaeology. He had secured about $630,000 from ten investors, including a sizable investment from Perry. The magazine quickly took off, and Leach soon rolled out additional publications, but the business crashed just as fast. Perry said he lost all of his investment as well as trust in his brother. “He couldn’t control himself,” Perry said. “He kept hiring too many people. And we couldn’t make payroll, and we couldn’t pay the payroll taxes.” Many subscribers never received their magazines. Leach had also advertised a travel package for exclusive tours guided by some of the biggest names in Egyptology, including a boat trip down the Nile led by the famous Egyptian actor Omar Sharif. But the trip never happened. Leach blamed unrest in the Middle East and then the 9/11 terrorist attacks. He promised refunds, but they never materialized. Customers’ advance payments went to cover operating expenses, including Leach’s salary.

Subscribers who never received copies of the magazines and customers who had signed up for the travel package eventually banded together and convinced the Texas attorney general’s office to open an investigation, which resulted in a 2003 default judgment of $130,000 against Leach. But he didn’t respond to the litigation and failed to appear before the judge—in the words of James Daross, the lead investigator on the case, he had “skipped town” by moving to New Mexico.

In October 2004, Leach emailed Daross, asking how he could pay the restitution. “I start [sic] sending payments your way,” Leach wrote. Daross never heard from him again. He tried to seize Leach’s assets but was denied access to his bank accounts in other states—as Daross later explained to me, he had no jurisdiction outside Texas. (Leach did not respond to requests for comment about the case.)

In 2006 Leach and a business partner launched World’s Healthiest Pizza, a restaurant in New Orleans. In 2009, with an investment from Dallas billionaire Mark Cuban in hand, Leach and his business partners began to rapidly expand the restaurant chain—now dubbed Naked Pizza—into at least ten states. An unhappy investor later pointed out that the principals in Naked Pizza failed to disclose the Texas AG’s action against Leach, which was required by the franchise agreement.

A half dozen former employees remembered the Naked Pizza office as a volatile environment. They recalled Leach’s frequent outbursts of anger, particularly toward his young female employees; they said he would regularly berate the women in front of other colleagues. His assistant said he threw a sandwich at her head. (Leach did not respond to requests for comment about Naked Pizza.)

Jessie Hawkins met Leach in 2009, when she was a student at Tulane University, in New Orleans. One of Leach’s pizza joints was near campus, and Hawkins started working as a delivery driver, moving up the ladder as the franchise expanded. As she worked more closely with Leach, she began to feel uncomfortable with what she saw as inappropriate situations. One evening in July 2011, he invited Hawkins to stay with him at a house he was renting in Arizona; according to Hawkins, while they were sitting together, Leach asked her if she wanted to sleep in his bed that night. She declined.

When Hawkins returned to New Orleans, Leach began to send her explicit texts, which she shared with Texas Monthly.

“Did u try and f— last week,” Leach texted her.

“Excuse me?” Hawkins replied. “No?”

“Really????” Leach responded.

“Really.”

Leach also sent her several photos of two young employees, a woman and a man, that Hawkins described as sexually suggestive. When Leach returned to New Orleans, he promoted the young woman in the photos, who had traveled to Arizona with him, to a prominent role in the company. Leach’s actions caused an uproar among the employees of Naked Pizza. Not long after that, Hawkins said, the key code to the office was changed without her knowledge, which she alleges was an act of retaliation after Leach’s co-owners became aware of his texts with her.

“I felt forced to quit,” Hawkins said later. She filed a claim of sexual harassment with the Louisiana Commission on Human Rights. Investigators asked her loaded questions insinuating that she was at fault, she said, so she ended up dropping the claim.

Meanwhile, the pizza business was growing fast—too fast. By 2013 Leach had left Naked Pizza behind, along with some unhappy business partners, moving to Terlingua either that year or the following. According to Cuban, Leach fraudulently used his name to raise money, and several investors “were not happy with him.”

Through the short-lived success of Naked Pizza and the attention it attracted in the media, Leach became a nationally recognized expert on dietary health. In 2012 he wrote an op-ed for the New York Times, headlined “Dirtying Up Our Diets,” in which he was identified as “a science and archaeology writer and founder of the Human Food Project.” He self-published several books on the subject (at least one was advertised for sale on the Human Food Project’s website, on a page that claimed, “100% of the proceeds go to support our work in Africa and Mongolia”). He traveled to Tanzania in 2013 and 2014 to collect fecal samples from the Hadza, an isolated community particularly vulnerable to outsiders because of its status as one of the few remaining hunter-gatherer tribes in Africa—and shared his research with legitimate academic institutions, coauthoring papers with some of the field’s biggest names.

“I HATE THE WAY THAT MANY OF HIS DREAMS WERE SHATTERED. IT WAS JUST PURE SPITE.”

After his 2014 stint with the Hadza, Leach published a post on the Human Food Project blog recounting the time he had performed a DIY fecal implant. The post created a lot of buzz, but it also drew criticism from scientists who questioned Leach’s methods and intentions (in a New York Times op-ed, science journalist Ed Yong called Leach’s microbiome experiment a “stunt” that was based on “faulty” reasoning).

Still, Leach and his research achieved new levels of publicity. He spoke at the Aspen Ideas Festival and was the lauded subject of a long profile in Science magazine; he was written about glowingly in the New Yorker and was featured in a PBS documentary about food based on a book by famed science writer Michael Pollan. The articles often repeated claims that Leach had earned a PhD, though the universities varied from story to story. In court documents filed in 2018 that were included in his lawsuit against Anderson, Leach admitted that he had never earned a master’s or PhD, and he couldn’t provide evidence that he had received even an undergraduate degree.

Meanwhile, the Human Food Project was growing. An early online crowdfunding effort raised $339,000, and between 2016 and 2019 the organization received more than $1 million in grants from charitable organizations, some earmarked for his research on the Hadza. In 2019 the IRS revoked the Human Food Project’s nonprofit status: Leach hadn’t filed the documents required for financial transparency. By December 2020, the organization’s website had been taken down.

But by then, Leach had bigger problems.

V.

As the defamation suit Leach filed against Schwartz progressed, Leach’s attorney filed a lengthy response in December 2019 to most of the allegations that had been made against him, alongside affidavits from Leach, Oakley, and three female Basecamp employees who said they had never witnessed any sexual misconduct from Leach.

“I did not force myself on or assault Katy Schwartz in anyway,” Leach said in his affidavit. “Any contact between us was totally mutually consensual.” As he described it in the affidavit, he and Schwartz played “footsies,” and then Schwartz “approached” him and “began to kiss” him. They were “making out” for ten to fifteen minutes before she left. (Schwartz responded to Leach’s allegations by calling them “complete fabrications.”) He denied inappropriately touching Berg and claimed that his sexual encounters with Thompson had been consensual. (The response did not address Johnson’s allegations—her affidavit was filed afterward.)

In her affidavit, Oakley said she had “never heard any allegations concerning any assaults by Jeff Leach” in the five years she’d known him. But according to messages she sent to Berg in July—five months before Oakley filed the affidavit—Oakley was aware that Thompson was “telling people that Jeff raped her” and had spoken to law enforcement. “By all means if [Thompson] was ‘raped’ she needs to go to the cops with details and proof or shut the f— up,” Oakley wrote to Berg, who had just come forward to Oakley via Facebook message about her own allegations of sexual misconduct against Leach. “[Thompson’s] notoriously known as a crazy person and obviously just as manipulative as Katy.”

Also attached to the filings were messages from Schwartz in the days following the alleged assault, including one that Schwartz sent to a coworker an hour after the alleged assault, in which she described a “good talk” with Leach, punctuated by a thumbs-up emoji. There was also a photo of Berg, Schwartz, Oakley, Leach, and two other women together on a bed at Berg’s house, smiling, taken a few weeks after Leach allegedly put his hand up Berg’s shorts. Leach’s response seemed meant to suggest that the women had not acted in a manner one would expect of victims of sexual violence.

But according to Gina Wilcox, of the Family Crisis Center of the Big Bend, there is no “typical” response to sexual or gender-based violence. “What we do see a lot of times is that people try to put on a face of normalcy,” she said. “They don’t want to be seen as a victim, so they will try to continue on with business as usual.”

Schwartz responded with another affidavit, explaining the messages. “I was in shock and unsure of what I should do, so I decided my best course of action was to act as normal as possible,” she said. “I was also afraid to lose my job and [of] Jeff’s violent tendencies . . . I did not feel like I had a choice not to be nice and friendly at first.”

Jodi Cole, Schwartz’s attorney, said, “They really trotted out all of the slut-shaming things they possibly could do . . . That is just capitalizing on those archaic stereotypes of how trauma affects us.”

In early February 2020, a judge dismissed Leach’s defamation lawsuit. Two weeks later, I emailed Leach to ask for an interview. I told him I wanted to hear his side. He replied that he “would be glad to chat” and said he and Oakley were currently in Austin, where I live. “I’d be delighted if u came to our little place over in Lakeway,” Leach wrote, referring to the generally well-to-do neighborhood that sits on Lake Travis. “Easy to spread out and I have a coffee pot.” He ended the message with a smile emoticon.

On February 25, the day I was supposed to meet Leach for the interview, Leach’s attorney, Rae Leifeste, called me and said that Leach had to return to Terlingua to handle some unexpected issues with his properties. As we talked, Leifeste asked me if I’d researched Schwartz’s background as extensively as I had researched Leach’s. He asked if I’d discovered that Schwartz had a felony charge for possession of marijuana (I had; she’d pleaded guilty to a Class A misdemeanor) and told me that Leach had no idea what I was referring to regarding alleged misconduct while he was at Naked Pizza.

Leifeste characterized the women who came forward in Terlingua as being “upset that they were being broken up with” by Leach. “They were disgruntled,” Leifeste said. “They were jilted girlfriends who now are coming forward, much after any of these events.” I asked if he had information that could help determine the credibility of Leach’s accusers, but he declined to provide any.

He acknowledged that the sexual assault allegations against Leach were serious and should be investigated. “However,” he added, “what if those stories are totally wrong and Mr. Leach loses his profession, his job, his companies, his reputation, all based on false allegations? What if those are false?” Leifeste didn’t respond to any of my questions after that conversation.

That same February day, Leach was indicted on a second-degree felony charge of sexual assault of Thompson. He was arrested four days later. During a virtual hearing in December 2020, Leach told the court that he had rejected a plea offer, and the case is expected to go to trial this summer.

Meanwhile, no new charges have been filed. Sandy Wilson, who served as the district attorney for Brewster County when Leach was indicted, said in an email in June 2020 that the other women had accused Leach of groping or attempted rape, acts that had for years been categorized as Class C misdemeanors under Texas law. But that law changed in 2019, when the Legislature passed a bill creating a new criminal offense called “indecent assault,” which includes unwanted touching with the intent “to arouse or gratify the sexual desire of any person.” State lawmakers heard sexual assault survivors describe feeling unprotected by law enforcement after being groped or otherwise sexually touched without consent. One advocate for survivors described the penalties of the original law as amounting to little more than a “speeding ticket.” Now a Class A misdemeanor, the offense carries the possibility of up to a year in jail and a $4,000 fine.

Wilson said last year that she planned to use the additional allegations against Leach to strengthen the prosecution of the Thompson case. “They will be used as bad acts during [Leach’s] trial to show how he operates,” Wilson said in an email. “When you only have one outcry as an adult, it is a toss-up for a jury. But when several women who did not know each other speak out, credibility increases.”

But in March 2020, Wilson was defeated in the Republican primary. Her replacement, Ori White, was sworn in on January 4. Wilson, who had worked as an ER nurse for decades before she attended law school and became a lawyer, told Texas Monthly in February that her four-year tenure as DA had been a constant struggle to work within what she called a “good ol’ boy” system. “It was just hard because they discounted everything I said,” she said. “It took me twice as long to get anything done.”

Wilson said that her attempts to prosecute cases involving sexual misconduct or the mistreatment of women were typically met with resistance from local law enforcement. It was a particular struggle, she said, to convince the sheriff’s office to pursue an investigation into Leach. “They didn’t think it was important, and they thought that girl was full of shit,” she said. “They were like, ‘Who cares? It [happened] in 2014.’ The sheriff’s department just was not interested in working that case.

“They just don’t take crimes against women that seriously,” she added. “I’m glad I’m out. You can only fight that so long. Let me tell you, it’s hard when you’re the only one trying to do the right thing and everybody is against you.”

Sheriff Ronny Dodson, a self-described conservative Democrat, disputed Wilson’s characterization, pointing out that his office investigated Thompson’s allegations and referred the case to Wilson in September 2019. “We make the case, we gather the facts, and we give it to the prosecutors,” Dodson said. “What they do with it then, we don’t have any say over that.” He added that he found Thompson’s account credible (“when she told me her story, it made me sick”) and is no fan of Leach’s. “He’s a good manipulator, he’s good at bullying people basically.”

VI.

News of the indictment did little to shake the faith of Leach’s supporters. When I spoke to about a dozen of them last summer, they offered a wide range of reasons for their continued backing of Leach. One person implied that the criminal indictment happened only because Wilson was up for reelection; others speculated that the allegations were largely orchestrated by a competing business owner in Terlingua. No one had hard evidence of these supposed conspiracies, though they were quick to suggest Schwartz had a sordid, deceitful history and shouldn’t be trusted.

“I think that she was making advances toward him and was rejected,” said Jim Ezell, an organizer of Terlingua’s annual chili cookoff. “I think she was a woman scorned.”

“I hate the way that many of his dreams were shattered,” said Les Hall, a part-time resident of Terlingua who had known Leach for a little more than a year. “It was just pure spite.”

“He’s more of the victim, in my opinion,” said Frann Brothers, a longtime Terlinguan who had recently moved to Arizona. During our short phone call, she said she’d never talked to Schwartz.

Several of Leach’s supporters tried to convince me not to write this article, saying it was a bunch of small-town gossip. Those who did talk on the record spoke of how generous Leach had been to his neighbors; how he’d given them financial support at some point; how he employed them or their friends and family; that he paid a good, living wage.

They spoke of how the Jeff Leach they knew was incapable of the sexual misconduct described by his accusers. They said the women must be motivated by greed or jealousy; they questioned why victims like Berg had waited so long to go to the authorities. They characterized Schwartz as a liar, said that she drank on the job at Basecamp, and accused her of being promiscuous and untrustworthy. They suggested that she had a criminal past, doesn’t pay child support (Schwartz says this is not true), and had made the allegations because she was worried about losing her job.

They expressed disdain for what they felt was unfair coverage by the local media and pointed to a February 2020 article about the sexual assault allegations in Science magazine—which raised questions about Leach’s scientific work—as evidence that the allegations were ruining Leach’s life outside their small town. Airbnb removed Leach’s rental listings from its website, citing the company’s policies on sexual misconduct; the University of California, San Diego, which had partnered with Leach in his microbiome research, edited part of a 2018 press release touting one of Leach’s major journal articles so that the release no longer refers to him as having a PhD. Meanwhile, he has appealed the judge’s dismissal of his defamation suit against Schwartz.

Since Johnson came forward, she said, she gets the occasional eye roll at the grocery store or gas station. But she said it doesn’t bother her anymore. “Nobody cared when I disappeared in the community, when I fell off the face of the earth,” she said. “Nobody came to look for me to see how I was doing or check on me. I’m not going to let their little scare tactics and their childish bullying prevent me from talking. I’m tired. I’m tired of being afraid and being worried about what people are going to say.”

Johnson said she hoped I’d have the chance to talk to Leach and his supporters so that the story wouldn’t appear to be one-sided. But she expressed frustration that so many people seemed to blindly support Leach. “I wish that people would just wake up and ask themselves what makes us the bad guy,” Johnson said. “I don’t understand that.”

When Perry heard about the allegations against his half brother, one detail in Schwartz’s account stuck out to him: that Leach had allegedly told her that he gets what he wants. “When I read that, I thought, ‘Okay, that’s Jeff,’ ” Perry said. “I believe this woman. And I don’t even know who she is.”

In September, Schwartz moved to Georgia to work at a nursing home, where she cooks Southern comfort food for about a hundred residents. “I make cornbread every day,” she said. The job was a chance for her to do the kind of work she’d badly wanted to do for years, but it was also a chance to get away from Terlingua, where the reminders of her trauma were everywhere.

Schwartz also underwent eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, an increasingly popular form of psychotherapy for those struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder. The therapy, which is recognized by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, has helped her head off some of the violent reactions she’s had to what she experienced, enough so that she plans to move back to the Big Bend region and use her experience in Georgia to start a program to feed senior citizens. She’s not sure if she’ll return to living full-time in Terlingua, but she has no regrets about coming forward against Leach. “He’s been getting away with stuff for way too long,” Schwartz said. “And it needs to be over.”

Editor’s Note: The story has been updated to include comment from Sheriff Ronny Dodson.

Updated May 26, 2022: In late April 2022, Leach won his appeal in the civil case, allowing the defamation suit against Schwartz to proceed. On May 20, 2022, the criminal case against Jeff Leach was dismissed. Read the update here.

A version of this article originally appeared in the March 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Surviving Terlingua.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Crime