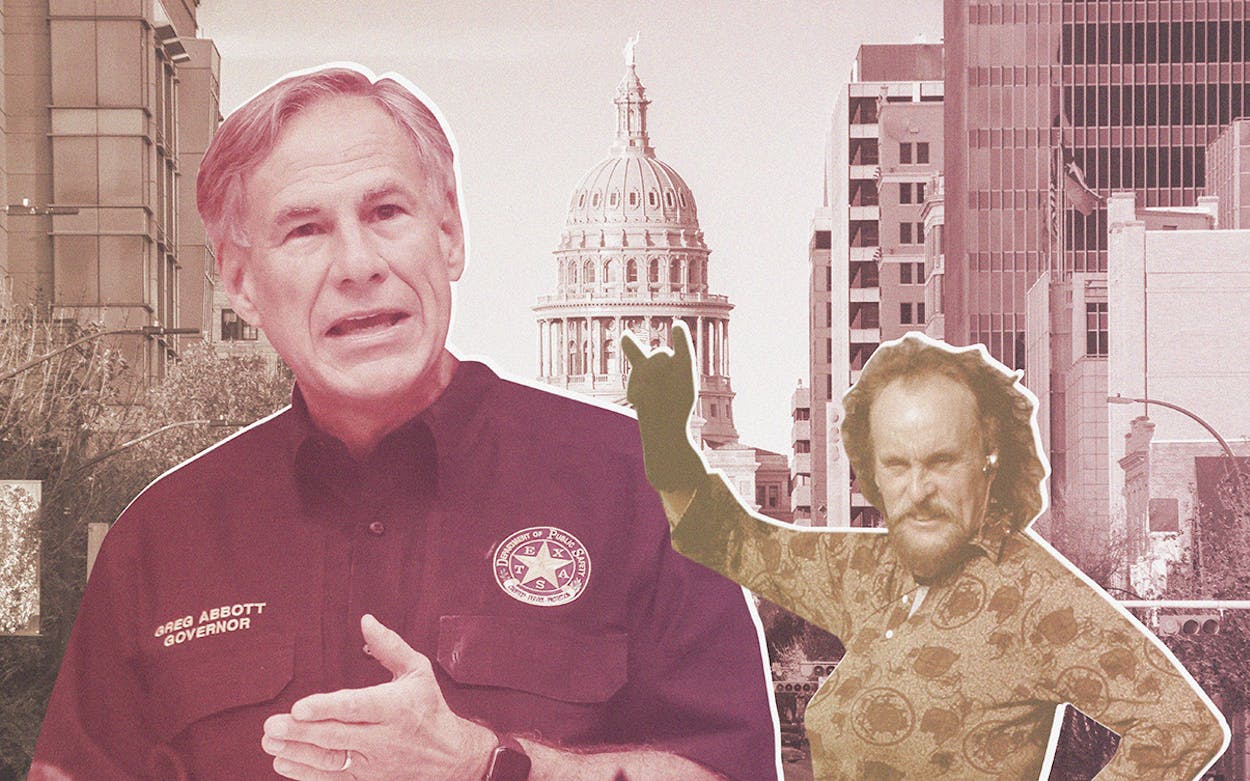

All patriotic Austinites kinda hate Austin, but not half so much as they hate outsiders hating on Austin—particularly when it comes from state government, and there’s quite a bit of that. The city used to be known as the “blueberry in the tomato soup,” a proud outpost of left-wing wackos. In truth, most of the state’s big cities are now blueberries, more politically aligned than they’ve been in many years. But Governor Greg Abbott’s letter on Wednesday threatening to put the city in a kind of receivership if it doesn’t “demonstrate improvement” with its “homelessness crisis” is proof that Austin’s relationship to the state nonetheless remains unique, in a manner that’s deeply irritating to many longtime residents.

The five gerrymandered congressional districts that contain part of Travis County splinter the city into manageable pieces like the Allies did to Berlin in 1945, and tie them with far-flung areas across the state, so that the eleventh most populous city in the United States has virtually no voice in Washington, D.C. (We share representatives with Houston, San Antonio, greater Fort Worth, and two big swathes of rural Texas.) The governor lives in a walled compound downtown, like Paul Bremer did in Baghdad’s Green Zone, issuing directives that tweak and poke at the city and its preferences, as do other statewide elected officials. The Legislature loves nullifying ordinances passed by the city council, though their batting record is getting worse than it used to be.

On some days, it can feel like we Austinites are a few bad turns away from building barricades around the Capitol building with our bongs, raiding the UT armory for its T-shirt cannons, and letting our breasts hang out like that one French lady in the old painting. But in truth, this crew doesn’t actually hate Austin—they like it when it’s useful, and are happy to take credit for, and pleasure in, its strengths and successes.

Whenever a big employer expands operations in Austin, like Apple did recently, all of state government claims responsibility for their stewardship of Texas’s “business climate,” omitting consideration of the reasons tech companies aren’t spending billions of dollars in Cleburne. There’s a grand tradition of lawmakers from around the state rushing to Austin to booze and fight and patronize the brothels on Congress Avenue before going home to their missuses and preachers and cattle, telling them all stories of escaping temptation in Sodom, a tradition that continues today in a somewhat more muted manner.

Which brings us to Abbott’s letter. On Wednesday, the governor plunged headfirst into a political controversy that has dominated discussion in the city since June. Back then, the city council partially neutered several ordinances that essentially made being homeless in the city a crime by allowing cops to ticket people for sitting or lying on sidewalks or camping in public places. As a result, homeless people became more visible on the city streets, to the consternation of downtown residents and business owners.

This has led to a tremendous improvement in the quality of life of many homeless people. The old rules meant they were pushed to unsafe places to sleep and live, where they were vulnerable to being raped, robbed, and assaulted. Many were ticketed or arrested dozens of times, inhibiting their ability to get off the streets. At the same time, it’s deeply unpleasant to bear witness to extreme poverty and desperation, and some downtown residents have spoken about dirty streets and feeling unsafe.

Austin’s changed. Have you heard that before? For about fifteen years starting in the late nineties, the city’s unofficial mascot was Leslie Cochran, a renowned homeless cross-dresser and political activist. When I was growing up here the whole charm of downtown Austin was that you could be walking along and look over and see a bony ass in a leopard-print thong sticking out of a dumpster. Now you see gelato bars and very expensive condos. Downtown Austin’s economy is built on visitors, and the fight over the homeless ordinances has won national attention.

A compromise is going to have to be found, and some restrictions put back into place, in order to make the situation downtown more palatable to the public. That’s what local governments do, and in fact what the Austin City Council has long planned to do. (A strong argument could be made that the city messed up by not instituting the restrictions when they changed the ordinances.) They failed to do so at the council meeting in September but planned to do so in October. Then Abbott cannonballed into the pool.

The letter is deeply strange. It consists of two parts: why Abbott is acting, and what he’ll do. The first bit contains a declaration that “as the Governor of Texas, I have the responsibility to protect the health and safety of all Texans, including Austin residents.” That’s a big responsibility, one that makes Abbott sound a bit like the All-father, and it might sound strange to you if you’ve come to think of the governorship as a traditionally ornamental sinecure where people earn a paycheck while they wait to run for president.

The line is footnoted, which looks good and proper, but when you follow the footnote it goes to the section of the Texas Constitution that basically just says there is a governor, and that he’s the head of the executive branch of state government. Presumably the fellows who wrote the 1876 constitution, ex-Confederates scalded by their hatred of Reconstruction-era activist governors, didn’t plan to give future governors the power to supervise “the health and safety of all Texans,” but who can say? They’re all dead and were mostly jerks anyway.

The second part lays out what the governor might do to Austin, and by what powers. The most alarming is the declaration that the Department of Public Safety “has the authority to act” to “enforce the state law prohibiting criminal trespassing. If necessary, DPS will add troops in Austin areas that pose greater threats.” It would be a significant overstatement to call this martial law, but the prospect of the governor deploying a surge of state troopers to Austin streets to selectively enforce laws is—well, bizarre, and a little unsettling. Other Texas cities should take note.

But he also lays out actions he could take through the Department of Transportation, the Health and Human Services Commission, the Department of State Health Services, and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. All of these are a bit weird, too. TCEQ, he says, could get involved “if increased human defecation caused elevated concentrations of E. Coli” in waterways. But before the ordinances a lot of homeless people hid themselves on the banks of creeks, and, more to the point, the city council did not increase the rate at which homeless people poop.

In a darker note, Abbott states that DSHS has the power to put in place quarantines and other “control measures,” which might be necessary because homeless people have a higher rate of “hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, and tuberculosis” than the general population. It is unclear how state troopers will address this, or whether the state has a plan to help homeless people once they go back into hiding. All of the above, the letter says, is “a sampling, not an exhaustive list” of the powers Abbott might exert over the city unless Austin fixes the problem in a way that satisfies him by November 1.

There’s been talk lately that the governor feels a keen need to look and act decisive on something big and visible, partly because of the widespread derision he’s received for his actions and inactions after the mass shootings in El Paso and Odessa. This ticks the box.

But it’s also probably not a coincidence that Abbott’s intervention in Austin’s squabble is coming at the same time that the Trump administration has vowed its own kind of nebulous action to “fix” the homelessness problems in big American cities. Both are vowing action to take homeless people off the streets—rather than find a way to provide them with stable housing—in the hope that decisive action gains them ground among the kind of voter that normally votes for Republicans but switched parties in the 2018 election, people for whom local “quality of life” is an overriding issue.

There’s a notable and telling omission among the list of agencies Abbott has said will “help” Austin with its problems: the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs, the state agency that helps build affordable housing. There’s been no real effort from state government to actually aid the city here, just a demand that they “fix” things. And in truth, Abbott could singlehandedly help the homeless population: with winter coming, a great many of Austin’s 2,200 or so homeless people could be housed on the floor of the Texas House and Senate, if Abbott were to arrange to put up cots.

If the Legislature were to object, the governor could point them to his letter: he has a responsibility to “protect the health and safety of all Texans,” including homeless ones. But it seems unlikely he’ll do so. If the city council somehow fails to act to the governor’s satisfaction this month, residents must be prepared for the occupation.

So, sisters and brothers: gather your leopard-print thongs. We’ll meet at the first sign of friscalating dusklight, in the empty Emo’s storefront. No, not the Riverside Emo’s, the old Emo’s complex. No, not Emo’s Jr., the thing next to it on the corner that used to be a Mexican restaurant or something that was sort of like an Emo’s club for probably a year or two before the rents went up too much. Yeah, that one. The password is “Manchaca.” Vaya con dios!

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Homelessness

- Steve Adler

- Greg Abbott

- Austin