FOR THE PAST TWENTY YEARS, Mike Toomey has loomed large in state government, as imposing and immovable—and some would say as cold—as the pink-granite Capitol itself. First as a Republican legislator, then as the Capitol’s premier business lobbyist, and now as chief of staff to his longtime friend Governor Rick Perry, the intense 53-year-old Houston lawyer has promoted a steadfast conservative agenda with little tolerance for compromise with—or mercy for—his adversaries. These include Democrats, plaintiffs lawyers, opposing lobbyists, and anybody else who stands in his way. His nickname, Mike the Knife, originally referred to his budget-cutting proposals as a legislator but now conveniently describes his propensity to carve up his enemies. With his encyclopedic knowledge of state government and his reputation as a ruthless political operative, he is positioned to help Perry challenge the old saw that the governorship of Texas is a constitutionally weak office. He is unquestionably the most powerful—and the most feared—nonelected person in Texas politics today.

And so, at the beginning of my interview with Toomey in his oak-paneled Capitol office, I was surprised when he mentioned how much he had enjoyed a job he had held to put himself through Baylor University, working as an aide in a treatment center for emotionally disturbed teenagers. Mike Toomey providing solace for troubled youths? The same Mike Toomey who is determined to slash social programs in the state budget, who as a hard-nosed business lobbyist campaigned to defeat lawmakers who dared vote against him, who is credited with getting his enemies in the lobby fired? Had I missed something in my research? I was struggling to conjure a mental picture of Toomey comforting adolescents when he explained: “I was basically in charge of discipline,” he said, fixing his steady gaze on me, “the heavy when the kids got out of hand. I was the enforcer of the rules.”

Of course. The enforcer.

THE STAKES IN THIS FIRST legislative session of the Republican era are sky-high. The state faces a mammoth $9.9 billion budget shortfall, for which the Perry-Toomey solution has been to cut spending rather than raise taxes. Perry is also pushing for a sweeping reform of tort laws that will make it harder for injured people to win big jury awards against business. Sometime in the next few weeks, Perry is likely to find himself in a battle with Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst, a fellow Republican and the leader of the state Senate, who favors more spending, with the help of “non-tax revenue,” and a more balanced, though still strongly pro-business, approach to tort reform. The winner will determine whether the primary power over legislation in general and the budget in particular remains with the Legislature, as the authors of the 127-year-old state constitution intended, or flows to the governor—a development that was unthinkable as recently as the previous legislative session, in 2001.

The old ideas about Texas government are in jeopardy. They may prove to be relics of a dead political tradition, one that was rural, Democratic, and loosely organized. Today, a new political tradition is being established, one that is suburban, Republican, and tightly controlled. At the heart of that new tradition are Rick Perry and his enforcer, Mike Toomey. With a huge mandate from the voters, unassailable Republican majorities in both the state House and the Senate, and a major budget crisis that justifies gubernatorial intervention, Perry is poised to become the most powerful governor of modern times. And Toomey is providing the brains and the muscle.

In the Capitol game of Clue this year, he is everyone’s favorite suspect: Mike Toomey did it, in the governor’s office, with—what else?—the knife. Why did the Texas Medical Association part company with its longtime lobbyist, Kim Ross, last December? Because Perry told the doctors’ group that his office would not work with them as long as Ross was around. (The TMA backed Perry’s Democratic opponent, Tony Sanchez, in the 2002 governor’s race after Perry, at Toomey’s urging on behalf of two clients, vetoed the doctors’ top-priority bill in 2001.) Why did the State Preservation Board, dominated by Perry appointees, fire its executive director, former GOP legislator Rick Crawford, whose tenure included the construction of the highly regarded Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum? Because Crawford refused Toomey’s request for his resignation, his apparent sin being friendship with Perry’s archenemy, former Democratic House Speaker Pete Laney. Why did several Democratic representatives have a change of heart in late March and vote for a proposed constitutional amendment limiting lawsuit awards? Could it be because the governor’s office informed them that funding for a regional health center in the Rio Grande Valley and a medical school for El Paso depended upon local lawmakers’ support for the tort-reform bill? Many more dark and dirty deeds are attributed to him without proof, as occurred with Karl Rove in the Bush years.

After two decades as one of the leading political operatives at the Capitol, Toomey has accumulated the skill and the will to influence every issue of consequence. And all the indicators are that Perry is ready to let him do so. The two men have been friends since they served in the House together, in the mid-eighties, when Perry was still a Democrat. As their career paths diverged in the late eighties—Perry leaving the Legislature to run statewide for agriculture commissioner as a Republican, Toomey leaving to operate behind the scenes—the friendship became even closer, as Toomey became Perry’s most trusted adviser. (Their relationship transcends politics; Toomey served as Perry’s attorney in a deal involving Perry’s sale of prime residential land to computer magnate Michael Dell for a $330,000 profit.) When Perry stumbled through his first two years as governor, Toomey blamed bad staff work. Eventually, Perry prevailed on him last fall to give up an annual income that is widely thought to have been in the seven figures to take the job as chief of staff.

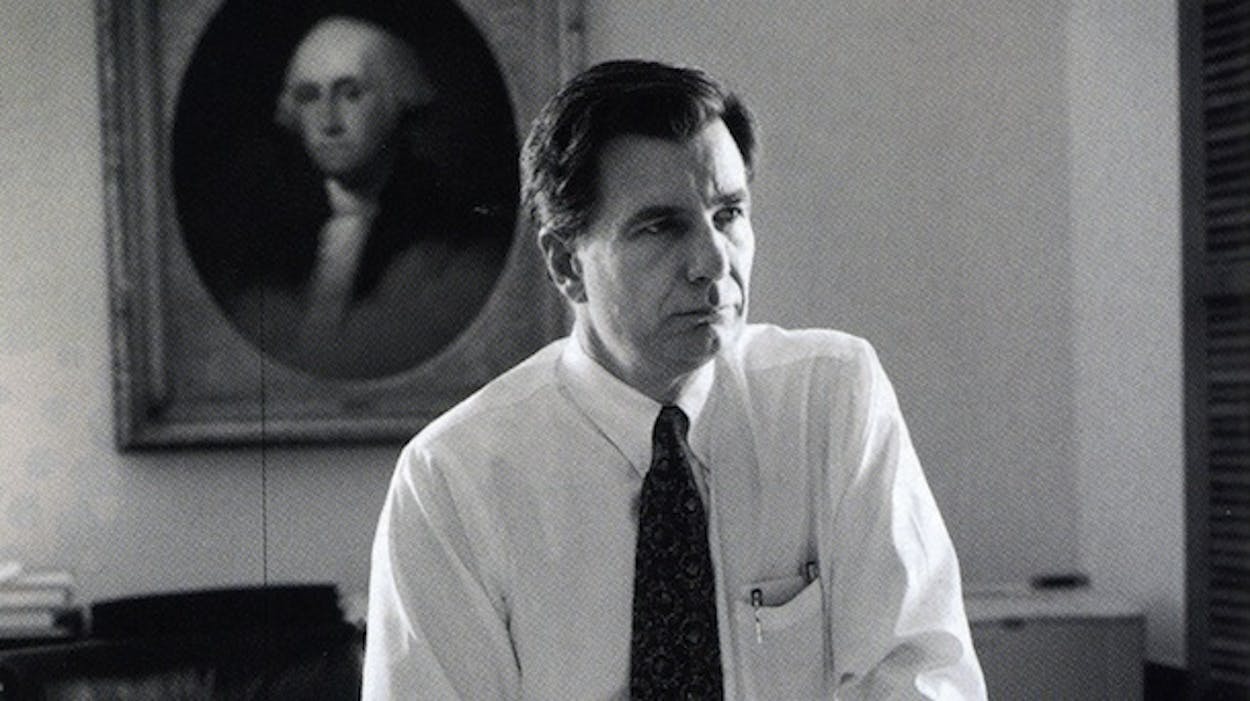

In addition to unquestioned loyalty, Toomey brings to the job a work ethic that has been legendary since 1985, when, as a new member of the House Appropriations Committee, he set about dissecting the state budget. “It was novel to see someone work that hard,” recalled Jim Rudd, then chair of the committee. Toomey is all business; when he remarried seven years ago, friends noticed that he was wearing his beeper on his tuxedo—and conspired to set it off during the ceremony. Another asset is his connections. After he set up his lobbying practice, he landed a blue-chip client in Texans for Lawsuit Reform (TLR), a group of influential Houston business leaders who were bent on changing state tort law to make it more favorable to defendants—a cause Toomey had championed as a legislator. He had a hand in dispensing more than $1 million in campaign contributions that the TLR donated every election cycle, almost all of which went to Republicans. In addition, Perry received some $3.2 million over five years from individual TLR members. By the time Toomey sold his lobby practice, in December, the new GOP majority in the House of Representatives included dozens of Republican legislators who had been bankrolled by Toomey and the TLR. Above all, Toomey brings to the governor’s office a forbidding reputation that works to Perry’s advantage. He approaches issues with a zeal and tenacity that even his detractors admire. Everything about him speaks of discipline. The day of our interview, he sat erect and spoke decisively. When he answered the phone, he paced behind his stand-up desk, in constant motion. He wore a white button-down shirt, a dark tie, dark pants—and two beepers. With his thin physique and thick, dark hair, he might be called youthful-looking, but his manner is brisk and businesslike.

As we retraced his career, I remarked about how often he had played the role of the “tough negotiator”; indeed, this phrase was the first description of him by nearly everyone I interviewed. He nodded in agreement. “I think I am used as the bad cop regularly because I don’t mind doing it,” he acknowledged unapologetically. “I do feel very strongly about certain things, and I do feel very passionately about a limited role for government. That’s why I’m a tough negotiator, and to tell you the truth, that’s why I came back here to help Governor Perry.”

MICHAEL TOOMEY III GREW UP in Houston, the eldest of three sons in an Irish Catholic family undermined by his father’s alcoholism. His dad, a lawyer whose practice ultimately failed because of chronic drinking, divorced his mother when Toomey was around twelve years old. He saw little of his father during his teenage years, though he sometimes went with his brothers for weekend excursions to the family’s bay house. “We went down there to see our father,” he recalled, “but everybody was just drunk. Just a bunch of drunks hanging around smoking and drinking.”

His mother, Rosemary, returned to teaching at St. Vincent de Paul, the Catholic grade school Toomey attended before going to all-male Strake Jesuit College Preparatory. He credits her hard work and frugality for influencing his conservative outlook. “Because we didn’t have much money, she was very prudent,” he said. “She would say the old expressions everybody my age grew up with: ‘Eat everything on your plate; people are starving.’ So I learned to be frugal about my own money. I worked all the way through high school and college.”

He selected Baylor University because he wanted to go to a small college. “I was pretty shy,” he said. “I’m still pretty shy. I don’t think I come across that way, because I can be very aggressive, but around people I’m still very shy.” Though tuition would have been cheaper at a larger, public university, Toomey decided he could handle the expense of Baylor with the help of scholarships, loans, and odd jobs, including enforcer at the adolescent treatment center. He intended to pursue medicine, but he struggled with science courses, and by the end of his sophomore year, he was looking for a new major. Then he signed up for a philosophy course taught by a professor who hit an intellectual nerve. He went on to major in the subject.

“Who is your favorite philosopher?” I asked.

“Oh, boy, is this going to get me in trouble,” he said, covering his face with his hands. “It was Nietzsche. Back in that time, I got caught up in existentialism. I was fascinated by it, and he was the top star there.” Toomey now attributes his God-is-dead phase to the general unrest of the late sixties. “Others rebelled by doing other things,” he recalled. “I rebelled by getting into existentialism.”

After Baylor, he returned home to Houston, still unsure of what he wanted to do with his life. He got a job on the psychiatric ward of Bellaire General Hospital, serving in much the same capacity as he did in the Waco treatment center. (He met his first wife there, a nurse named Mary, and the couple had two girls. They are now divorced; he remarried in 1996 and has two children, ages four and one, with his second wife, Stacy.) A few months later, he entered South Texas College of Law and began assisting his father with cases. “His practice was deteriorating,” Toomey said. “At some point, he couldn’t do it anymore, but I got some on-the-ground experience.”

After he earned his law degree, he became involved in civic affairs—the West Houston Chamber of Commerce and the Optimist Club. A friend suggested that he run for the Legislature in 1982, and he campaigned against higher taxes. “When you speak to Republican women,” he said, “you order little trinkets for them. So I had a little bottle of hand lotion that said, ‘Don’t get chapped over higher taxes. Vote Mike Toomey.'”

In what was then a gregarious, backslapping, nights-on-the-town atmosphere in the Legislature, Toomey didn’t fit in, even on the detail-oriented House Appropriations Committee, to which he was appointed in his second term. “His personality made people nervous,” recalled committee chairman Jim Rudd. “He didn’t have much of a sense of humor.” One evening, Rudd and several of his committee members went to a local bar for a drink. They invited Toomey and were surprised—because of his grinding work habits—when he showed up. As he got up to leave, Toomey tossed a $10 bill on the table for the tab. The committee members had it framed and presented it to him: It was the first time they had seen him part with money.

In his third session, in 1987, Toomey left the Appropriations Committee to handle a successful, though mild, effort at tort reform. But he remained involved in budget issues; when the appropriations bill reached the House floor, he led a futile Republican attack against it. Later, Toomey led a Republican bloc that voted against a tax bill needed to fund the budget, even though GOP governor Bill Clements had signed off on it.

“I was really ticked off at Mike for that,” Rudd said. “We had done a good job on the budget, had scrubbed it as much as we could. He wasn’t willing to vote for the tax bill. It disappointed me. The party made him do that.”

Not so, Toomey said: “I thought that whatever we were short—three billion dollars—I wanted them to cut. Bear in mind that was on the heel of a tax bill in ’83 and a tax bill in ’85. At some point, it’s enough.” The incident has strong implications for this year’s session, in which the shortfall is almost $10 billion. You can be sure that Toomey’s philosophy hasn’t changed and that the son of the alcoholic father, who watched his mother struggle to make ends meet, will not have much sympathy for governmental programs that necessitate higher taxes.

“You’ve got to look at what the core purpose of government is,” he said. “It is not to do everything. The core element of government is to help people who can’t help themselves. Beyond that, it’s not a high priority.”

Toomey believes now, as he did when he led the attack on the budget in 1987, that lawmakers are poor stewards of taxpayer money. “I always felt [scrubbing the budget] was a ruse,” he said. “The committee pretends to want to cut. They do a little on the edge. But no one really structurally changes anything. No one went in there as I wanted to do and I believe we will do this time: start over and examine everything.”

TOOMEY’S 1987 TAX STAND INFURIATED Democrats, but it earned him admiration within his own party. When Clements asked former Texas Secretary of State George Bayoud to serve as chief of staff, Bayoud agreed on one condition: that he could hire Toomey and another former lawmaker. “They agreed and I got a press release out before they changed their minds,” Bayoud recalled.

Toomey’s job in the 1989 legislative session was to keep Clements from having to sign another tax bill. This time he succeeded. “We did everything humanly possible—cut lots of money, did lots of smoke-and-mirrors maneuvers, and browbeat insurance companies into settling [a dispute with the state] for hundreds of millions of dollars,” he said. Former state senator Kent Caperton, now an Austin lobbyist, who served as the Senate’s budget chairman that year, reflected on Toomey’s hard line with the insurance companies: “He’s a helluva negotiator. One of the things he has learned is not to reach a deal too quickly. You can hold out and hold out.”

That was exactly the tactic Toomey took during a prolonged fight over workers’ compensation reform later that year. Employers were crying out for a complete overhaul of the insurance system for injured workers, and the powerful Texas Trial Lawyers Association opposed the changes. Toomey held out so long, in fact, that Bayoud was afraid that the chance to make a deal might pass. “Don’t be so unflinching that we lose it,” Bayoud told him. In the end, Toomey said, “It was a big victory.”

Later, lawmakers had to deal with a school-finance crisis. They passed a quarter-cent sales tax increase, which Toomey urged Clements to veto and, for the first time, took on the role of the enforcer. In a news story about the controversy, the Dallas Morning News noted that Toomey was collecting signatures from Republican legislators who promised to vote to uphold a possible veto. According to the story, Toomey said that lawmakers who refused to sign would have to answer to the voters—and might find Clements backing their opponent. “Their vote is a vote against their Republican governor and it’s a vote for higher taxes,” Toomey told the newspaper. Bayoud intervened, telling Clements to sign the tax hike because his veto would be overridden. While Toomey “might not have liked” his advice to the governor, Bayoud had praise for the role Toomey played. “Mike is tough. He’s into policy. He’s well-versed. Mike knows the numbers. It’s hard to maneuver around him because he knows his stuff,” Bayoud said. “And a lot of times, the governor wants you to stay tough.”

Two dominant themes had emerged in Toomey’s career: an aversion to higher taxes and a deep conviction that lawsuits were harming Texas businesses. Today, those two issues once again are at the heart of the legislative session, and once again Toomey is in a position to do something about them—only this time, Republicans are in control.

Toomey got the chance to turn his tort-reform philosophy into his profession when he began his lobby practice, in 1990. In 1994 he gained a new client that would propel him to the top rank of business lobbiest when a group of Houston businessmen headed by homebuilder Dick Weekley hired him as the chief lobbyist for their new organization, Texans for Lawsuit Reform. Toomey not only got paid to promote legislation that he believed in but the political contributions he dispensed through the TLR helped change the makeup of the Legislature. In 2000 the TLR donated 92 percent of its $1.4 million war chest to Republicans.

“Mike would never lobby for someone he didn’t agree with philosophically,” says Ric Williamson, another old friend from Toomey’s legislative days, who is also a member of Perry’s inner circle and a Perry appointee to the Texas Transportation Commission. “He has passed up fees because he would not work for something that was not his cause. His tort-reform views are that a bunch of lawyers are gaming the process and not trying to achieve justice.”

Getting the TLR as a connection cemented Toomey’s stature as the Capitol’s top business lobbyist and as an enforcer. Before the TLR came along, most lobby groups took a live-and-let-live attitude toward lawmakers who didn’t vote their way—but not Toomey. Many a legislator has grumbled about feeling threatened that the TLR would find an opponent to run against anyone who failed to support bills helping business defendants in lawsuits. “Sure, we’ve heard that,” said Ralph Wayne, the president of the Texas Civil Justice League, another tort-reform lobby group. “It’s a feeling that has gotten around, but I’ve never found any evidence of it.” Yet few would dispute that the TLR’s campaign contributions produced a Senate majority for the Republicans in 1995 and contributed to a GOP House majority this year. “He’s very aggressive and some people take umbrage,” Wayne acknowledged. “He’s never rude. But he doesn’t spend a lot of time chatting.”

THE BEST KNOWN EXAMPLE OF Toomey’s enforcement technique was his play to oust Kim Ross as the head lobbyist for the Texas Medical Association. At the beginning of Toomey’s efforts to change Texas tort law in 1987, doctors were advocates for tort reform. A large number of frivolous lawsuits had made it hard for doctors to get affordable malpractice insurance. Toomey helped pass a compromise tort-reform bill that year, but he felt that the TMA had been too willing to compromise with the plaintiffs lawyers. The rift grew worse when managed care came along, in the nineties. Doctors found themselves at the mercy of health maintenance organizations that dictated what they could charge and how they treated patients. In 1995 the TMA made a truce with its old enemy—the Texas Trial Lawyers Association—to pass legislation allowing HMOs to be sued for malpractice. Business-oriented lobby groups, employers, and the TLR opposed the bill, which Governor George W. Bush vetoed. Bush later made peace with the doctors by having most of the bill’s provisions adopted as rules by the state agency that regulates insurance.

Perry reopened the rift in June 2001 by vetoing the TMA’s top legislative priority, a bill requiring insurance companies to pay doctors promptly. Toomey opposed the “prompt pay” bill, unsuccessfully, on behalf of an insurance company client and the TLR. After the session ended, however, he lobbied two top Perry staffers for a veto, according to a Dallas Morning News report. This time he was successful. Whether Toomey raised the TLR’s objections during the session, when there was time to fix the bill, or after lawmakers went home remains in dispute. Doctors and their supporters cried foul. John Coppedge, a politically active Longview physician and a Republican, asked Toomey why he didn’t express his reservations to TMA lobbyist Ross. According to a widely circulated letter from Coppedge about the conversation, Toomey replied, “Dr. Coppedge, you don’t understand. Those people are the enemy.”

Ross met with Toomey over lunch a few weeks after the veto. Toomey, said Ross, “laid out in the most thorough, methodical, detailed manner why he felt I was involved in a national conspiracy [with the trial lawyers]. We ended up on the grassy knoll. It was a highly reasoned argument and fundamentally one hundred eighty degrees off from reality.”

Last November, following Perry’s easy victory over Tony Sanchez, the governor’s office said it would not deal with the TMA as long as Ross remained in charge. Ross said he resigned his position after it became clear that he would not be able to represent the doctors with Perry as governor. “Any deviation from Toomey’s philosophy is considered heretical and you get shot to death. Look at me,” Ross said. He now represents clients on issues pending in Congress, and the doctors rely mainly on outside lobbyists. Even Toomey’s close friends agree with Ross that Toomey views the world in absolutes. “He sees the world as good and bad, evil and pure, right and wrong,” said Ric Williamson. “You’re not a little bit right.”

IN LATE MARCH THE HOUSE of Representatives fought for two weeks over a TLR-backed tort-reform program that was weighted heavily in favor of business defendants. Even before the debate unfolded, tempers flared when the bill’s House sponsor, Houston Republican Joe Nixon, absorbed a popular bill aimed at reducing medical-malpractice insurance rates into the controversial tort-reform proposal. Although there are several stories about who thought up the clever stroke, Toomey is generally given credit for it. The stratagem worked, and the House passed the tort-reform bill by a wide margin. Asked if he saw Toomey’s fingerprints on the combined bill, Dallas Democrat Steve Wolens, an opponent, responded, “I don’t see his fingerprints. I see his brain prints.”

A common complaint heard around the Capitol is that Toomey “hasn’t taken off his lobby hat”—meaning that as Perry’s chief of staff, he continues to argue positions favorable to his former clients, especially the TLR. Toomey was ready with his answer when I raised the point in our interview: “I have two responses to that. First of all, I didn’t have any client that I didn’t agree with philosophically about what they were doing. Just go through my client list. I don’t have clients I disagree with.” The second rebuttal was that he delegates issues on which he has lobbied previously to other staffers. As an example, he said he sent representatives of SBC Communications (Southwestern Bell) to an assistant, who could take the company’s concerns directly to the governor, since Toomey himself had worked as a lobbyist for its competitor, AT&T.

But word that Toomey had participated in a meeting on a resurrected prompt-pay bill, advocating a position favorable to employers and insurance companies and anathema to doctors, swept the Capitol early in the session. “I was involved—with the governor’s blessing,” Toomey acknowledged. “I came in hoping I could get an agreement on prompt pay and not have those two groups [employers and doctors] fighting. We failed. We couldn’t bridge them together.”

Toomey’s involvement on behalf of his former clients might become a major problem if he returns to lobbying for them, but Williamson says that is unlikely. He and other friends predict that Toomey will return to electoral politics, running for a statewide office like comptroller, or alternatively, go to work for a conservative advocacy foundation.

As we were winding up our interview, I mentioned to Toomey that many people had suggested that I wait until after the session to write this article, when the inflammatory issues of the budget and tort reform would be settled and they would be freer to talk.

“Are you saying that people are afraid of me?” Toomey asked, incredulous. He collapsed in his chair and looked at the ceiling, as if in despair—but just for a second. Then the enforcer collected himself and gave what sounded like a final argument to a jury: “If people are going to pass bills that are going to regulate business, if they want to make it more costly to do business here, if they want to raise taxes, if they want to get government more involved in people’s lives or businesses’ lives, I’m going to tell the governor, in my opinion, he ought to veto it.”

And he closed with the comfortable air of a man who suffers no self-doubt. “If people are afraid of that,” he said, “I don’t know what I can do to appease them.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy