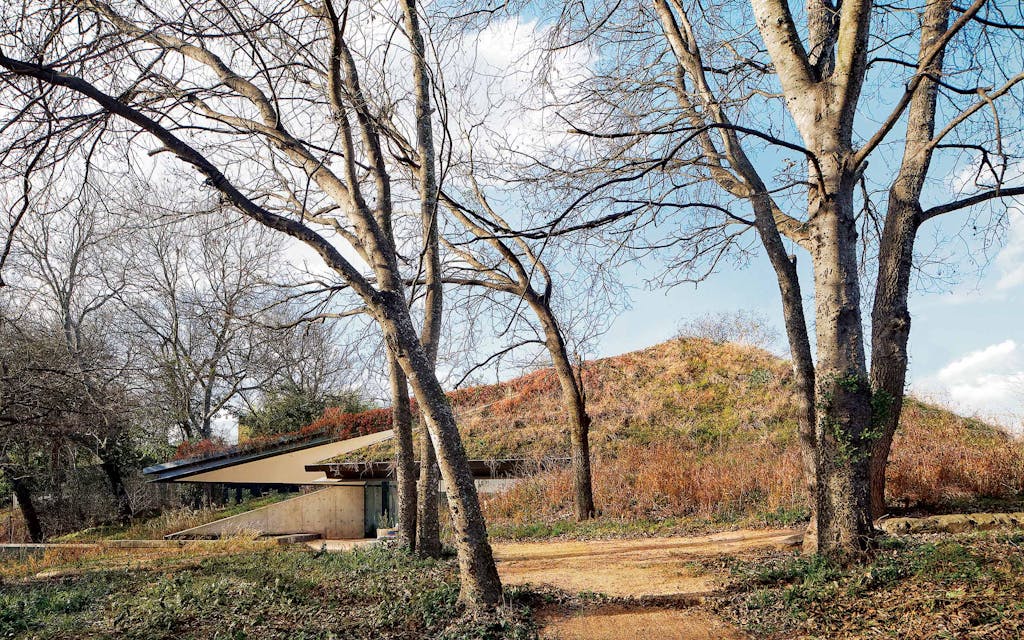

The East Austin home of lawyer and critically acclaimed novelist Christopher Brown is difficult to see from the street, and not just because it sits at the back of a one-acre lot near the Colorado River. Called the Edgeland House, which the architects loosely modeled on a Native American pit house, the dwelling is buried some seven feet into the earth. The structure’s two separate triangular roofs blend seamlessly into the landscape. In fact, because they also serve as a miniature Texas blackland prairie habitat, they are very much a part of it.

The roofs were spiky-haired and wild with plants when I met with Brown on a late fall afternoon. I followed the writer and his rescue dog, Lupe, along a rocky path in his purposefully overgrown front yard. He pointed out a family of sunflowers, all taller than myself, and gave me a heads-up to sidestep a spiderweb that was under construction. I also narrowly missed walking into an armadillo burrow, and then I almost crushed the largest grasshopper I’d ever seen. Feeling the urge to put my shirt collar up to protect against more insects, I was glad I’d worn sensible boots.

As we descended the fourteen wide concrete steps leading to the front door, the heat of the day suddenly lifted. Standing at the bottom of the stairwell felt like arriving at the entrance of a narrow canyon—but instead of rock, floor-to-ceiling windows soared on either side. The house is relatively small, at 1,400 square feet, and is split into halves, divided by a walkway that opens onto the back patio. To the left of the walkway is a private space containing two bedrooms and two bathrooms; to the right, a public space with an open kitchen, living area, and powder room. When I entered the guest-friendly side, my gaze was immediately drawn to the view outside, where dragonfly traffic was at its peak. Brown joked that he lived in a terrarium—but one in which the bugs watched him. With another door leading to the back terrace, the house nudges you outside, which is where we ended up.

As we settled into patio chairs, an orange-and-black American lady butterfly landed on Brown’s crisp white shirt, pulsed its wings, and flew off. I looked up at the foliage cascading from the roof over a window and saw more wings. A creature, possibly a bird or lizard, rustling in the depths made the crossvine flowers jiggle. A pleasant trickling sound came from the unchlorinated triangular swimming pool, which Brown deemed “the world’s most posh birdbath.” I recognized it from Brown’s weekly newsletter, Field Notes, in which he documents urban nature and seasonal changes in his backyard. In one photo, cedar waxwings enjoyed the pool as if they were having a personal spa day.

Brown has lived in the Edgeland House, which he commissioned, for ten years. He was traveling in Oxford, England, when he first heard the word “edgeland,” a term coined by British writer Marion Shoard to describe the liminal space where the natural landscape and urban life meet. “It sounded like a place where you’d find postindustrial hobbits,” Brown said. Ever since he moved to Austin, in 1998, he’s sought out pockets of “the urban wild,” exploring greenbelts and secret beaches where nature thrives undisturbed. Not long thereafter, driving over the Montopolis Bridge, he looked down and spotted a pristine stretch of the Colorado. His son was a Cub Scout at the time, so they returned with a canoe to explore. They hadn’t paddled very far before they saw a hawk swoop down and grab a duck with its talons. It was easy to forget that downtown Austin was only a few river miles away.

When a property near the same stretch of water became available, Brown was interested. It was what some might call a “problem lot” because it was a former industrial site and came with an asbestos-wrapped petroleum pipeline. Whereas most buyers would have run in the opposite direction, Brown saw it as an ideal spot for a house that would “harmonize that abrupt transition between the heaviest of human development and the pocket of wild nature allowed to exist in a secret corner of the city,” he told me. “I also just wanted a cool house for my son and me.” (Brown was divorced at the time.) He reached out to architects Thomas Bercy and Calvin Chen, of Austin’s Bercy Chen Studio, who designed a split structure made of poured concrete, steel beams, and wood.

He was drawn to the pit house design because it would make the home feel like a bunker. Like the pipeline, which was removed, the house would be embedded into the land, but instead of posing an environmental threat, it would provide a healthy habitat for plant and animal species to flourish. He also wanted the house to be no larger than the 1,400-square-foot, two-bedroom apartment he’d been living in with his son.

The Edgeland House’s green roofs are perhaps its most magnificent feature. In consultation with ecologists and designers from Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, the Edgeland team selected plants that would be able to handle the Texas climate. Not only have the roofs lived up to the overgrown aesthetic Brown was looking for, but they also attract ecological surprises, from bright yellow partridge pea plants to Gulf fritillary butterflies.

Not only have the roofs lived up to the overgrown aesthetic Brown was looking for, but they also attract ecological surprises, from bright yellow partridge pea plants to Gulf fritillary butterflies.

As we talked, Brown pointed to the top of the steps, where the pipeline’s valve wheel once emerged. The outdoor passageway between the two structures is where the pipeline used to lie. After it was excavated, workers arrived and donned blue hazmat suits to test the soil for contaminants. The results came up clean, except for one finding: a colony of about 10,000 venomous red harvester ants in a mound tunneling deep underground. The team covered it with dirt.

Living in a house burrowed into the ground proved beneficial during last year’s winter storm. On February 15, Brown woke up at around three in the morning, sensing that something was off. When you’re from the Midwest, he told me, you just know the sort of quiet that accompanies a lot of snow. He also noticed the house was lacking its normal ambient sounds: the power had been turned off during the blackout that would affect millions of Texans. While his wife, Agustina Rodriguez, and one-and-a-half-year-old daughter slept, he got up and shoveled snow to keep ice from forming. During the three days they were without power, the temperature indoors never dropped below 60 degrees—not cozy, but not dangerously cold. Because the outer concrete walls of the house are flush with about seven feet of earth, they get extra insulation.

As a business lawyer who is also a noted author of science-fiction novels, Brown admits that he’s attuned to the bizarre. His most recent book, 2020’s Failed State (Harper Voyager), depicts a government in shambles after a climate disaster. When the storm hit, Brown said, Austin felt eerily familiar and “authentically dystopian.” When he went to gas up the car and buy milk for the toddler, the city streets were in a state of what seemed like postapocalyptic chaos. He watched an SUV filled with men speed down the road with windows rolled down, as one passenger angrily shouted, “Get out of the way!” He saw someone wearing a scary clown mask with green hair as well as what looked like all the clothes from their closet. His next novel-in-progress (started a few months before the storm) is about a group of young Texans who learn to navigate life as the grid goes dark for months at a time. As we talked, he picked up his cellphone. “What happens when we can’t charge these things?”

A bit nervous about these predictions, I changed the subject. “So, what’s it like to weed your roof?” I asked. “It’s fun!” he said. Each spring, Brown and Rodriguez yank out invasive plants whose seeds have floated in on the wind or in bird droppings. He didn’t count on a hackberry tree inching its fat roots underground toward the house. While native grasses are just fine, what you don’t want, Brown said, are trees growing on your roof. At that very moment, a work crew was checking for any damage caused by the hackberry.

Brown suggested heading down to the Colorado, a quarter of a mile from the house. As we tramped down a bluff into the woods, he pointed out some chile pequin. He waved his hand over the river’s clean, clear water, saying, “This used to be a gravel pit.” It was also the site of one of the largest fish kills in U.S. history, written about by Rachel Carson in Silent Spring, in 1961. Now, decades later, it’s a spot where deer cross the river and white egrets and eagles leave feathers in the tall grass along the shore. The only hint that this postcard setting was five minutes from downtown was a new high-rise peeking out upstream.

I asked Brown about his neighbors. “My human neighbors?” he replied. “We’re all like-minded armadillo sponsors.” There’s an artist, a dancer, and some filmmakers on his street. He pointed in the direction of the nearby home of the couple from whom he bought the lot. He’s an entomologist and she’s a botanist. “They met because the bugs he studies were eating the plants she studies.” Brown has his own distinctive love story: he met Rodriguez through Bercy Chen Studio. She designed the exquisite pool.

Rodriguez has drawn up plans for a guest casita that Brown is building for friends and family, like his son, who is now in college. Brown also intends to add solar panels and a water catchment system. He had long hoped to make these improvements, but he feels greater urgency since last year’s blackout. “The goal,” he said, “is to get off the grid.” In other words, to go full hobbit.

Austin-based writer Julie Poole’s debut book of nature poems, Bright Specimen, was published in 2021 by Deep Vellum.

This article originally appeared in the March 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Living on the Edge.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Architecture

- Austin