The collection

104 globes.

The rarest item

An eighteenth-century pocket globe in its original sharkskin case—in its day, a status symbol for those who could afford “a fairly useless thing.”

The tiniest artifact

An Earth the size of a gumball that would have dangled from a nineteenth-century pocket watch.

The most unlikely location of discovery

In a bin of basketballs at Goodwill.

The collectors

“We’re all weirdos, just different levels of weirdo.”

Almost every night, as part of his wind-down routine, antiques dealer Jake Moore lies in bed in Central Austin staring at his phone. But he isn’t checking Instagram or Reddit—he’s scrolling through eBay, hunting old globes.

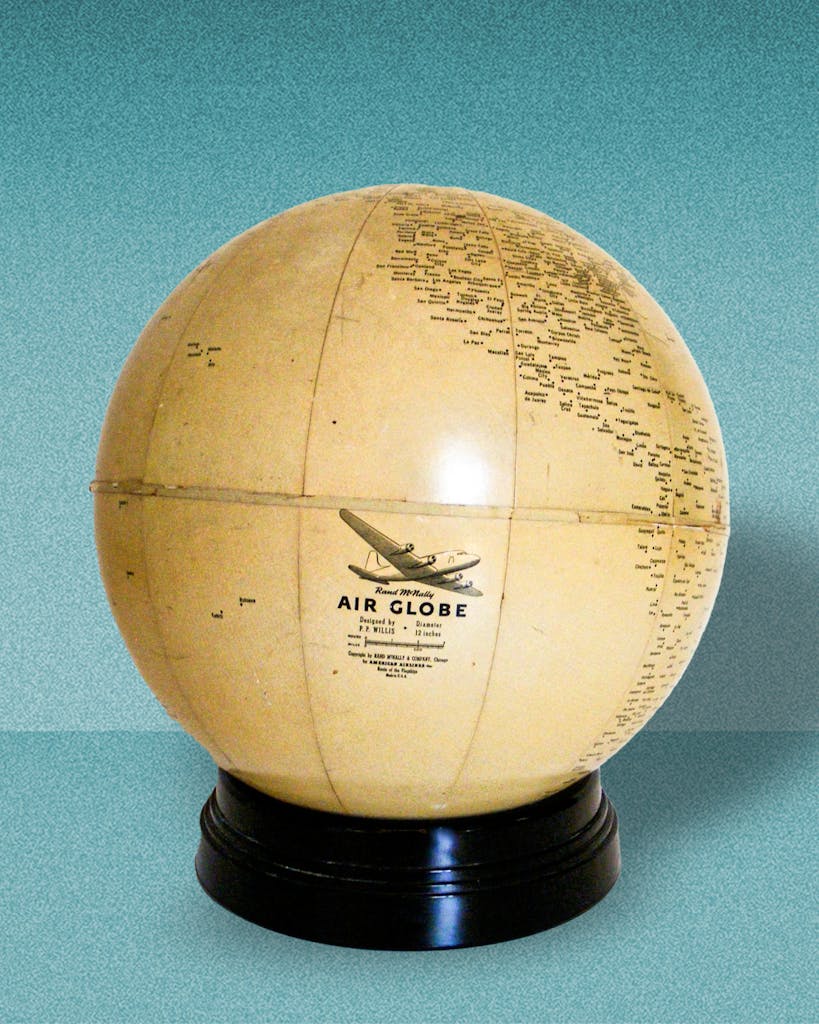

On a recent spring evening, as Moore weeded through hundreds of auction listings, his heart began to race. There, on his screen, was a twelve-inch Rand McNally globe, briefly manufactured for American Airlines in 1944 and blank but for the names of cities hovering like word clouds. “I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, oh my gosh, oh my gosh,’ ” he says.

The design had dazzled him when he last saw one of the globes a decade ago. Then, he didn’t have the requisite $500 to take it home. But he couldn’t forget about it and had searched for another ever since. “I couldn’t hit ‘Buy’ fast enough,” he says.

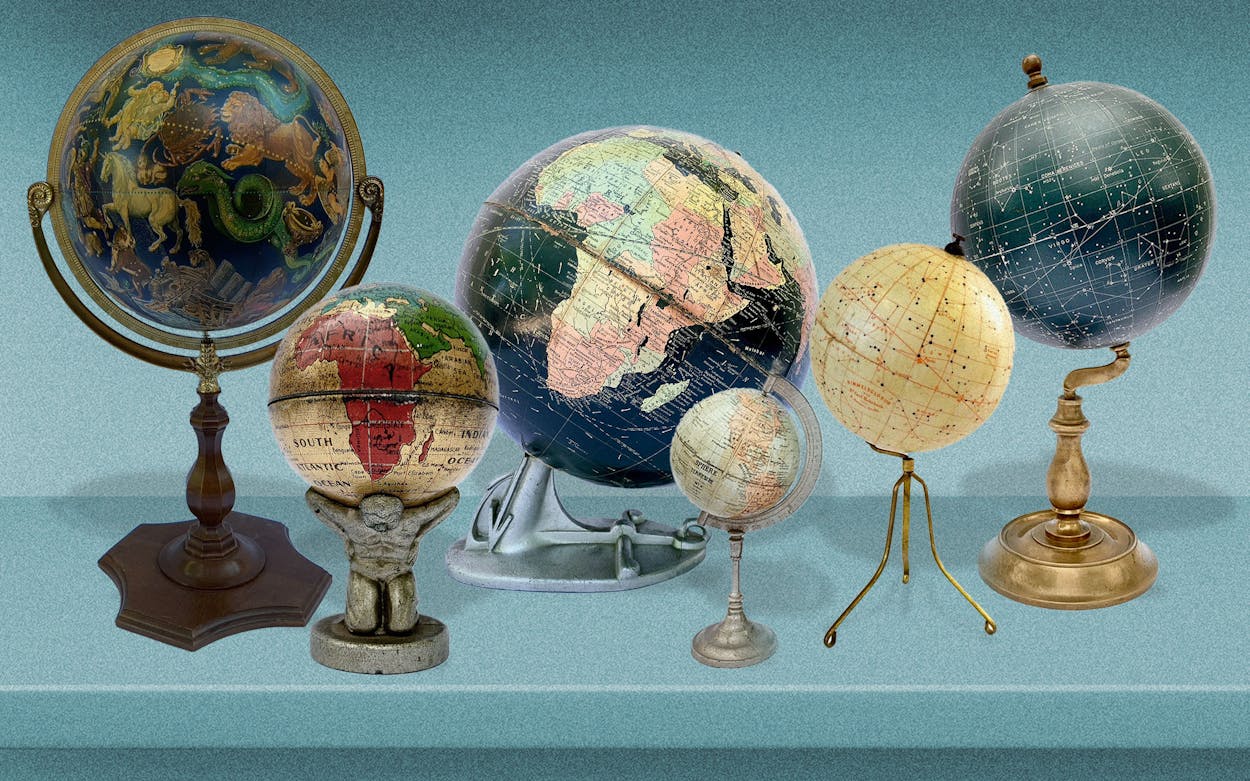

Whether he’ll keep it remains a question mark. Moore is a collector and dealer, and the boundaries of his personal globe collection are like those of the nations and territories the orbs delineate: shifty. Currently, he has 22 globes at his house, 10 in various states of repair at his workshop, and another 72 for sale through his website, Omniterrum, and at Uncommon Objects, an antique store in Austin.

At the shop’s front counter, amid a cluster of orphaned Earths, a miniature Greek god shoulders a globe the size of a golf ball, which opens to reveal a 1920s pencil sharpener. Another, no bigger than a gumball, is actually a nineteenth-century mechanical pencil, intended to dangle from a pocket watch and advertise the wearer’s worldliness. Entering citrus-size territory, a three-inch sphere with hand-applied map segments stands atop a paperweight that’s also a magnifying glass. The price tag underscores its rarity: what retailed in 1893 for $1, or $35 in today’s money, now goes for $1,250.

It isn’t the rarest orb Moore has come across. Last year he bought an eighteenth-century pocket globe with its original sharkskin case from a Facebook user who found it in his garage. In its day, it was a status symbol for those who could afford “a fairly useless thing,” and really, not much has changed. At auction, pocket globes now fetch anywhere from $2,000 to $150,000. Moore is evasive about what he spent on it, but he says it was the “same as a used car.”

It’s hard for Moore to say which came first—collecting or dealing. At age sixteen, he paid 69 cents for his first globe, which he found tossed in with the basketballs at a Goodwill in Temple. Years later, while working as an architect designing restaurants in Washington, D.C., he stumbled on his first decent find, a globe from 1900 that sat among the farm tools at an open-air junk shop. He fell in love with globes’ faded colors, elaborate cartouches, swirling ocean currents, and solid forms, the weight of plaster, metal, or glass conveying an elevated sense of importance that today’s plastic and cardboard varieties lack.

He was selling them online by the time he met Kim Soerensen, another dealer who ran an online shop and informational website for globes called Omniterrum. Ready for a career change, she asked Moore if he wanted to take over the business. He’d just quit his own job and was heading to Poland for an extended adventure, but he bought it anyway, officially joining a subculture that has counted both musician Moby and late Italian designer Gianni Versace among its members.

Some buyers just want a conversation piece for their bookshelf. Others are serious collectors, or married to them, like the woman who emails every time her husband needs a gift. One client was so dedicated that he built a sanctuary for his globes, complete with fine-tuned temperature and humidity controls. “It’s similar to me to fandom, like people who live and breathe Dallas Cowboys, spend tens of thousands of dollars a year going to games, and their house is a shrine,” Moore says.

Dealing gives Moore the thrill of the chase, the satisfaction of the buy, and the dopamine-fueled joy of possessing a fascinating historical object—being able to “study it, feel the weight, the tactile connection of it”—without the limitations imposed by his 951-square-foot home, which he shares with his partner and two dogs. It’s also an excuse to travel. Moore’s passports (he’s filled three) contain stamps from sixty-plus countries. He makes at least two buying trips a year, scouring thrift stores and markets from Tbilisi to Tokyo.

Dating his finds requires a Jeopardy-like knowledge of geography and its shifts. Texas, for instance, gained independence from Mexico in 1836 and joined the union in 1845, but it took a few years for different printers to reflect those changes. “It’s such a short window of time, so they’re really hard to find,” Moore says. That’s just one of many cartographical clues Moore looks for, and proof—as Bob Wills, the King of Western Swing, sang—that time changes everything.

Globes were often a way of documenting that change. They charted seafaring expeditions, Antarctica journeys, steamship routes, shortwave radio stations, and more. On a shelf in Moore’s office, a 1960s lunar globe doubles as a coin bank; a former owner stuffed it with newspaper clippings about the Apollo missions and annotated its surface with landing dates. It’s one of Moore’s favorite globes, representing a part of the cosmos that light pollution can’t block out, and reminding him of all that lies beyond it.

It’s that kind of extra layer of information that fascinates Moore, especially when it’s DIY. In the late 1940s and early fifties, a merchant marine in New York meticulously cut colored strips of paper to track his journeys on a twelve-inch Replogle library globe. “It sat on his desk, and he stared at it all the time, and maybe thought about where he went and what he did,” Moore imagines. It used to be part of Moore’s personal collection, but he recently decided to sell it to make room for others.

“I hesitate to call myself a permanent collector, because I think I have an ability to let go of things in a way that I don’t ascribe to a true collector,” he says.

As for the American Airlines globe, he’ll keep it, at least for now. As cool as it is, watermarks sully the paper, and chemicals leach through from the steel beneath, leaving dark spots like on a treasure map. He’ll part with it one day if he can find a better version. He’s already looking.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Austin