The English describe warm humidity by saying that the weather is “close.” If you think about it, it’s a perfect term to articulate the feeling of suffocation that accompanies dew-point levels in the 90th percentile, especially when the temperatures are equally high, a phenomenon with which Texans in the central and eastern parts of the state are well familiar. All of this to say that that the British Consulate’s May 6 celebration of the coronation of King Charles III at the Houston Arboretum would have looked and felt exactly like a quaint, happy traditional English garden party had the weather not been so unbearably f—ing close.

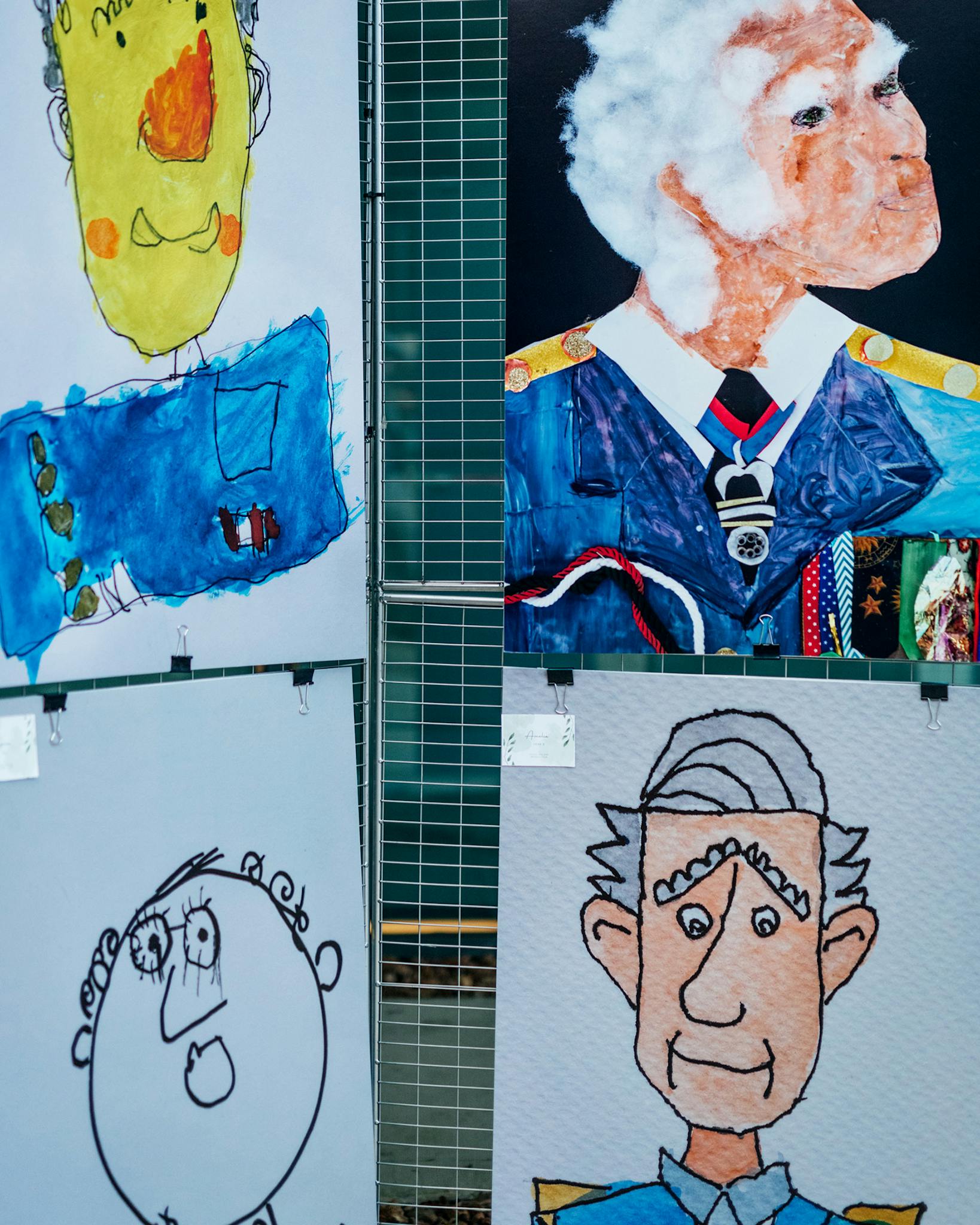

The event, which took place under a tent outside the arboretum’s nature center, was a sea of Union Jack flags and other British iconography. Guests could take photos inside a red London phone booth, or in front of a double-decker bus constructed from paint and particle board. There were a series of cute hand-drawn portraits of the king created by students at the British International School of Houston (many of whom had begun the day with a “coronation cleanup” at Buffalo Bayou). There was even a Big Ben, scaled down so it was barely taller than the life-size coronation portraits of King Charles III and Queen Camilla that were displayed right next to it.

The crowd wore fascinators, floral dresses, kilts, and suits and nibbled on tiny Sunday roasts—complete with Yorkshire puddings—and tea sandwiches. There was a special beer called “Charles in Charge” and cocktails made from Scottish gin and whiskey. Guests could play cornhole or croquet and take pictures at a green-screen photo booth that would transpose them in front of the Houses of Parliament. Beetle, Houston’s best Beatles cover band, headlined the night, though the Houston Brass Band was on hand to perform back-to-back UK and American national anthems.

“Close” also applied to the distance between guests, since there were around seven hundred people present—a fraction of the tens of thousands who lined the London streets on Saturday, but a larger turnout than that at the British Consulate’s party last summer to celebrate the seventieth anniversary of Queen Elizabeth’s reign (a somewhat surprising detail, considering she was a beloved cultural icon who had an 80 percent approval rating, and he’s still known in the U.S. mostly as the guy who made Diana cry). The news coverage surrounding the new king’s coronation has been dominated by the question “can the monarchy last, especially under this guy?” One certainly wouldn’t expect Texans, of all people, to rally hard for such big government, but nevertheless, there they were, decked out in festive party attire and posing for photographs in front of the other two people in Diana’s marriage.

“I would say three-quarters or four-fifths of these people are Americans,” British Consul General Richard Hyde (who had kicked off the week’s celebrations by having a giant Union Jack light show displayed on his River Oaks home) said during the party. “This is the ninth country I’ve lived in, and I’ve represented my country all around the world, and I’ve never been anywhere that has as much interest and affection for the royal family as the United States. And Texas has just been mind-blowing.” He thinks the enthusiasm has to do with a shared appreciation for rural life and an identity rooted in agrarianism, even though most people in both Texas and the UK live in cities these days. “Also, there’s individualism, and the notion that we don’t really need anybody else.” Texans, he says, have been far more supportive of Brexit than people he’s met in other parts of the United States. We do love a right to secede.

But this party was about succession, not secession, and I think its popularity had a lot to do with Houston’s worldliness. One of the most diverse cities in the United States, a day spent in Houston—meals in Chinatown or on Blodgett Street, an afternoon jaunt through Phoenicia Specialty Foods—can send one to other countries and continents. Locals are used to decking themselves out for a transnational fete. The event felt less particular to Charles and Camilla and more like a celebration of England, of its history, and of its peaceful transition of power.

Much like the coronation across the pond, the party was a real who’s who. Former Go-Go Kathy Valentine was there, as was 93-year-old socialite Joanne King Herring and Houston city councilwoman Letitia Plummer, who was attending with her entire office in support of her British-born chief of staff, Munira Bangee. I spoke to one consulate employee who was rushing around trying to meet coronavirus vaccine developer Dr. Peter Hotez (“I’ve missed him at our last two events,” she said). The team was especially proud of having tracked down former Kilgore Rangerette Lisa McCutcheon Walker, who had met then-prince Charles during his tour of Texas in 1986. (Asked about that meeting, Walker told me, “He beelined to the very, very beautiful girl next to me and said, ‘Aren’t your legs cold in those skirts?’ and she didn’t know what to say and I said, ‘No sir, we wear tights when it’s cold.’ ”)

Toward the end of the night, the catering staff put out a buffet of desserts, arranging macarons, mini cakes, tarts, and trifles into the shape of a Union Jack. It was very transportive. Looking around at all the flags and the garden hats and the cocktails in fine china teacups, with the official seal of the coronation plastered on nearly every sign, one could temporarily feel like they were on vacation in a foreign land, or at least binge-watching episodes of something on BritBox. One could only be taken out of the fantasy when one remembered the heat, or paid too much attention to the Texas accents, or, as I did, happen to see the catering staff refilling the water dispensers with a bag of ice that had a big old Buc-ee’s logo on it.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Houston